Полная версия

Collins New Naturalist Library

The now flourishing Royal Dublin Society was encouraging economic development of the country through agricultural improvement. Naturalists and scientists rose to the occasion. John White (d. before 1845), one of the gardeners to the Society, published An Essay on the Indigenous Grasses of Ireland in 1808.57 Wade came forward with Sketch of Lectures on Meadow and Pasture Grasses,58 which he delivered in Glasnevin at the beginning of the nineteenth century. William Richardson (1740–1820), rector of Moy and Clonfeacle, Co. Antrim, and a writer on geology and agriculture, engaged in a vigorous and eccentric campaign to promote creeping bent grass and brought out a Memoir on Fiorin Grass, published in 1808 as a Select Paper of the Belfast Literary Society. Another utilitarian natural history contribution was Wade’s most substantial book: Salices or an Essay towards a General History of Sallows, Willows & Osiers, their Uses and Best Methods of Propagating and Cultivating Them (1811).59

The scientific study of botany came of age before that of zoology. Plants were not elusive; they stayed put and lent themselves to scrutiny, whereas animals were much more difficult to observe, so botanical discoveries were continuing at an even pace. Belfastman John Templeton, (1766–1825) who furthered the cause of Irish botany more than any other, and was described by Praeger as the most eminent naturalist that Ireland ever produced, completed his manuscript Catalogue of the Native Plants of Ireland in 1801 – now in the Royal Irish Academy, Dublin. Unfortunately, he failed to realise his ambition of producing an elaborate Hibernian Flora that would have drawn from his Catalogue and embodied new records together with colour illustrations. The remaining manuscript, including some fine watercolour drawings by Templeton himself, is little more than a skeleton with some volumes now missing. It resides in the Ulster Museum, Belfast.

Templeton was quite content to live in Northern Ireland, working diligently on both the flora and fauna, with little ambition to travel abroad despite a tempting offer from the British botanist Sir Joseph Banks to go to New Holland (Australia), ‘with a good salary and a large grant of land’.2 Templeton published very little but maintained an active correspondence with many eminent British naturalists such as William Hooker, Dawson Turner, James Sowerby and Lewis Dillwyn (who also visited Ireland), many of whom published his records.

The first national flora was The Irish Flora Comprising the Phaenogramous Plants and Ferns, published anonymously in 1833.60 Katherine Sophia Baily (1811–86), later Lady Kane and wife of Sir Robert Kane, was the reputed author at the tender age of 22. John White of the National Botanic Gardens is acknowledged in the preface as having supplied the localities for plants. Three years later James Townsend Mackay (1775?—1862), a Scot who had been appointed Curator of the Trinity College Botanic Garden at Ball’s Bridge in 1806, brought forth Flora Hibernica,61 a much more substantial and scholarly work which ambitiously encompassed both phanerogams (seed-bearing plants) and cryptogams (those that do not produce seeds) of the entire island in one work. The book was a joint effort, despite no acknowledgement on the title page – the other contributors are acknowledged later in the text – between William Henry Harvey (1811–66) who was responsible for the section on algae and Thomas Taylor (d.1848) who wrote the sections on mosses, liverworts and lichens while Mackay dealt with the flowering plants, ferns and stoneworts.

Turner’s Muscologiae Hibernicae (1804). Although originating from England the book is well grounded on Irish data.

One of the few specially illustrated title pages for Baily’s Irish Flora (1833).

The British Association for the Advancement of Science, founded in 1831, was based, in the words of social historian David Allen, ‘ostensibly on the model of a similar perambulatory body started nine years before in Germany’. Apart from providing the natural history world as a whole with a usual annual meeting ground and forum, the B.A. helped these studies in a more practical way by making grants-in-aid.62 The B.A. provided enormous stimulus to the development of regional and local natural histories by holding its regional meetings throughout Britain and Ireland. The 1843 Association meeting was held in Cork and to mark the event the Cuvierian Society of Cork published a small volume of ‘communications’ entitled Contributions Towards a Fauna and Flora of the County of Cork.63 John D. Humphreys (fl. 1843) prepared the lists of molluscs, crustaceans and echinoderms; J.R. Harvey (fl. 1843) wrote on the vertebrates while Thomas Power (fl. 1845) was responsible for the section ‘The Botanist’s Guide for the County of Cork’ – one of the first local floras in Ireland.

Twenty years after the publication of the Cork regional flora came Flora Belfastiensis in 1863.64 Its author, Ralph Tate (1840–1901), hoped that it might be of use to the botanical members of the Belfast Naturalists’ Field Club which had been founded as an enthusiastic response to his series of lectures delivered at the Belfast School of Science. Tate, born in Britain, was only resident in Belfast for three years after which he travelled widely, ending up as Professor of geology at Adelaide, Australia. Another similar product was the small, slim volume A Flora of Ulster,65 published the following year by George Dickie (1812–82), and offered as a ‘Collectanea’ towards a more comprehensive flora of the North of Ireland. Dickie’s view of Ulster was definitely expansionist for he included parts of Connacht in the surveyed localities. Both Flora Belfastiensis and A Flora of Ulster consisted of a list of species accompanied with notes on their habitats and distribution.

A departure from the presentation of traditional floras came with the publication in 1866 of Cybele Hibernica66 by David Moore (1807–79) and Alexander Goodman More (1830–95). When living in England, More had worked with H.C. Watson who devised, for Cybele Britannica (1847–59)67 a scheme of 18 ‘provinces’ that were later split into 112 ‘vice-counties’, a first move towards the recording of plant distribution on a quantitative basis. This was the ancestor of the dot distribution maps showing the presence or absence of a species within a grid of 10 km squares, now the internationally accepted grid recording system.

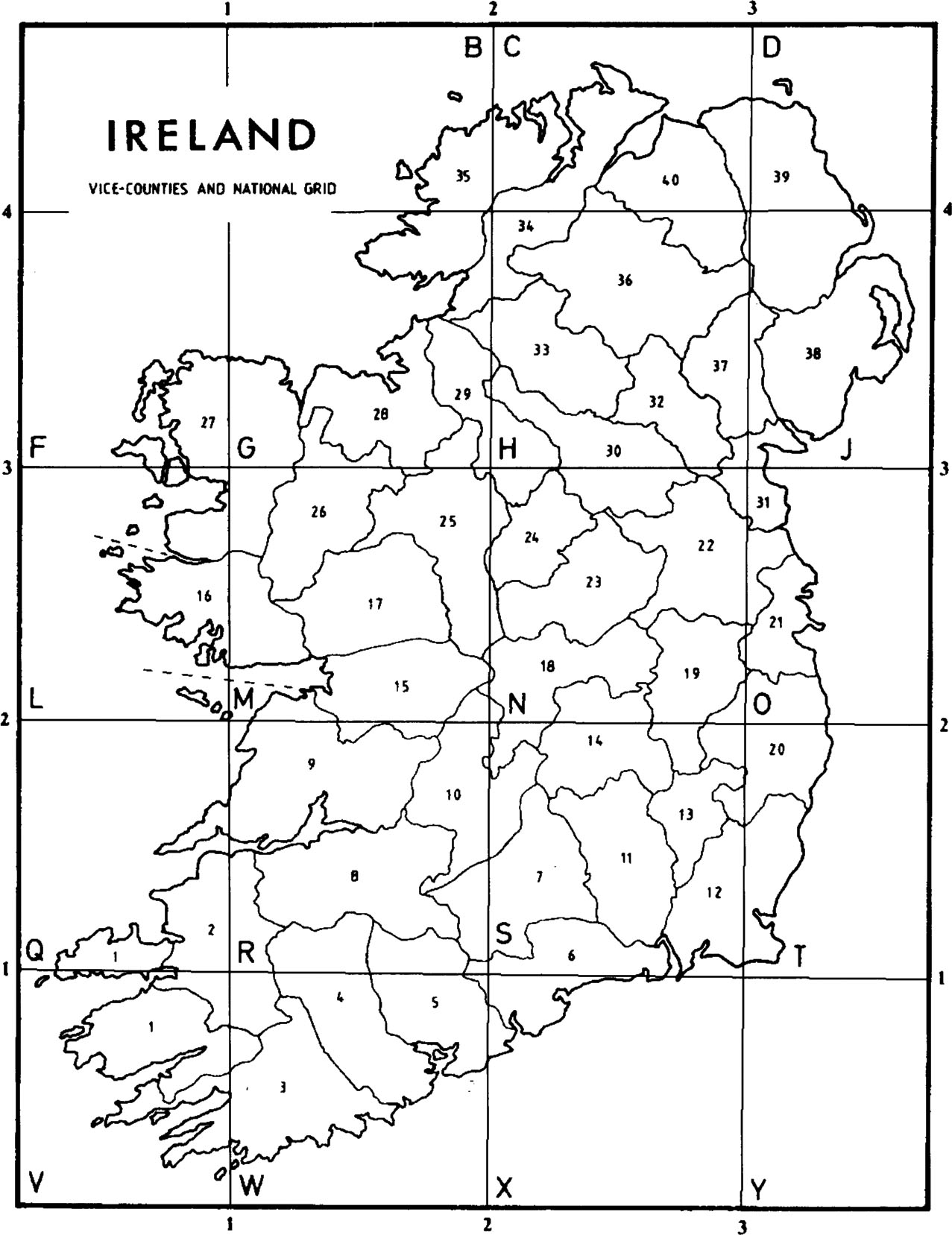

The division of Ireland into 12 ‘districts’ (based mostly on county boundaries) and 37 ‘vice-counties’ was originally proposed by Charles Babington (1808–95), Professor of Botany at Cambridge, in a paper presented to the Dublin University Zoological and Botanical Association in 1859.68 More, quick to see the advantages of such a scheme, adopted the 12 ‘districts’ for Ireland for his compilation of Cybele Hibernica. Plants now had a framework in which they could be recorded; their distribution could be compared region for region over time.

Such was the success of Cybele Hibernica that a supplement followed in 1872 and a second edition of the book in 1898.69 In 1896, shortly before the second edition, Robert Lloyd Praeger (see here) proposed an even more fine-grained recording net of 40 ‘divisions’ or ‘vice-counties’ (each an average 813 km2) based on the 32 administrative counties that comprised all Ireland.70 The new divisions were used in his monumental Irish Topographical Botany,71 published in 1900, the product of 35 years of active botanising, and have been adopted, subject to minor modifications, as the standard botanical recording units of Ireland. The distribution of plant records in the most recent 1987 Census Catalogue of the Flora of Ireland by Scannell & Synnott are referenced on Praeger’s 40 botanical ‘divisions’.72

The Rev. Thomas Allin (d?1909) served in several parishes in Ireland – Cork, Galway and Carlow – but apparently ‘botanised’ only in Co. Cork, when he possibly had more available time, and where he gathered his records for the Flowering Plants and Ferns of the County Cork (1883).73 He divided the county into two parts, shown on the book’s coloured frontispiece, which bore no correspondence to the system adopted in Cybele Hibernica. Allin was a careful recorder and listed 700 flowering plants and ferns together with notes on their distribution. In his preface he pays tribute to Isaac Carroll (1828–80), one of the best botanists in the county at the time. The extent of Carroll’s contribution to Allin’s flora is not known but it may have been substantial. The amount of information Allin published was a marked advance on Power’s earlier flora of Cork.

Botanical sub-divisions of Ireland based on vice -counties with the 100 km lines of the National Grid. The sub-zone letters are also given; each sub-zone is a particular 100 km square of the National Grid: B=14, C=24, D=34, F=03, G=13, H=23, J=33, L=02, M=12, N=22, 0=32, Q=01, R=11, S=21, T=31, V=00, W=10, X=20, Y=30. From Scannell & Synnott72.

From the bubbling crucible of Northern Ireland arose A Flora of the North-east of Ireland (1888)74 by Samuel Alexander Stewart (1826–1910) and Thomas Corry (1860–83). Stewart, an errand boy at 11 and later a trunk maker, played the leading role in founding the Belfast Naturalists’ Field Club in 1863. He was one of a select band of ‘working-men naturalists’ who transcended the social barriers and joined in with middle class hunters of flowers and plants. In 1891 he gave up trunk-making to become Curator of the museum of the Belfast Natural History and Philosophical Society. His colleague Corry was a brilliant and diligent botanist and a poet, who tragically drowned in Lough Gill, Co. Sligo, aged 23. Although the geographic scope of flora of northeast of Ireland is restricted to three counties (Down, Antrim and Derry) the book has been updated, revised and added to numerous times, the most recent edition being 1992.

One of the botanical ‘giants’ of Victorian Ireland was Henry Chichester Hart (1847–1908) who, according to Praeger, was ‘a man of magnificent physique, a daring climber and a tireless worker, and though his pace was usually too fast for exhaustive work, he missed little, and penetrated to places where very few have followed him’.2 Although Hart did not know any Irish he gathered the names and folklore of plants from country people, the results of which remained in manuscript form until 1953 when they were published by M. Traynor as The English Dialect of Donegal.75,76 Born in Dublin, where his father was Vice-Provost of Trinity College, Hart was of a Donegal landed gentry family and started work on Flora of the County Donegal (1898)77 when aged 17, having been inspired by Cybele Hibernica. It was the beginning of a 35 year task which took him on innumerable walks and hikes during which he collected more than half the many hundreds of records that were to enter his book – a remarkable achievement. In 1887 he published a more modest volume on the Flora of Howth.78 Like many before him, Hart was a naturalist of independent means working on a private basis and not affiliated to any state body.

Zoological natural history

Naturalists have historically focused more attention on Irish botany than on zoology, a fact reflected by the discrepancy between the two bodies of literature corresponding to the two areas. Animals are, however, catching up fast, as naturalists and scientists are spurred on by conservation requirements to discover more about endangered and threatened species. New resources for field studies together with advanced technologies are facilitating their task.

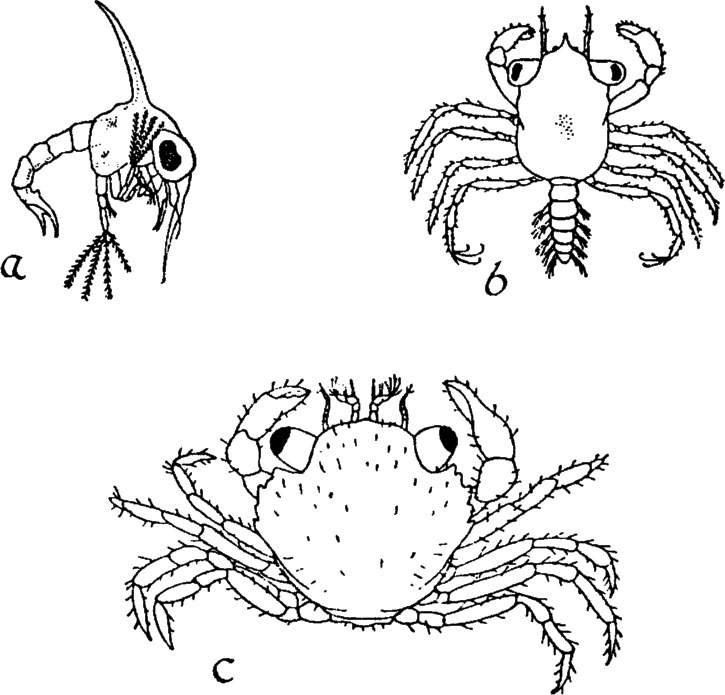

Some of the earliest and most original zoological investigations in Ireland were carried out by John Vaughan Thompson (1779–1847) who was born in Berwick-on-Tweed, England, and stationed at Cork in 1816 as Surgeon to the Forces, later Deputy Inspector-General of Hospitals, before going on to Australia in 1835. He was a specialist in planktonic larvae. It had been widely believed at the time that the fundamental difference between crustaceans and insects was that the crustaceans did not pass through different stages or forms in their development from egg to adult. Working almost alone, Thompson discovered that the edible crab did in fact undergo a metamorphosis and developed from a larval form called a zoea which had, until then, been classified as a species unrelated to the crab. Thompson was also responsible for the reclassification of acorn barnacles – the small symmetrical sessile barnacles exposed on rocks at low tide – from the Mollusca to the Crustacea, a major break with the accepted Cuvierian system of the classification of animals in force at the time. Cuvier and other contemporary zoologists believed, on the basis of external similarities, that barnacles were aberrant molluscs. Most of Thompson’s work was privately published in Cork in an obscure series of six memoirs bearing the – similarly obscure – title Zoological Researches, and Illustrations; or, Natural History of Nondescript or Imperfectly Known Animals in a Series of Memoirs, issued between 1828 and 1834.79

Stages (a-c) in the development of the shore crab. The discovery of the zoea larva (a) by zoologist John Thompson showed that the crab went thorough metamorphosis in its development from egg to adult, sharing this feature with the insects and uniting both as belonging to the Phylum Arthropoda. From C.M. Yonge (1961). The New Naturalist: The Sea Shore. Collins, London.

West Mayo, and especially the Erris peninsula, was the ‘ultima Thule’ of Ireland where William Hamilton Maxwell (1792–1850) retreated in 1819 from holding the curacy at Clonallon, near Newry, Co. Down, after disgracing himself by riding through his parish naked on horseback following an early morning dip in Carlingford Lough. The wayward curate then became a canon of the Tuam diocese and was appointed to three parishes. He befriended the Marquis of Sligo who gave him the use of his shooting lodge at Ballycroy on the edge of Blacksod Bay where he appears to have spent more time shooting, fishing and writing than administering his parishes. The stories of his adventures and encounters with eagles, otters, seals, grouse and wild geese make Wild Sports of the West, with Legendary Tales and Local Sketches (1832) a vivid read.80 It is an obligatory text, written along semi-fictional lines with many ‘ripping’ yarns which tell a lot about western Ireland, its wildlife and local lore during the early nineteenth century. His capability as a lively raconteur and his easy social manner gave him access to and accommodation with the British garrison in Castlebar, Co. Mayo, whenever he wanted it: ‘Maxwell introduced the officers to capital shooting, dined at their mess; and while draining their decanters drained their memories of those stirring recollections which he turned to account in Stories of Waterloo.’81 In between his fishing, hunting, drinking and socialising, Maxwell mustered enough energy to write 20 books. His ambition in Wild Sports was to ‘record the wild features and wilder associations of that romantic and untouched country’ – a goal he certainly honoured. Amongst his numerous observations, he recorded some of the last indigenous red deer of Mayo which were persecuted almost to extinction during his time with the aid of muskets abandoned by the French in 1798. He lost his ‘living’ of Balla in 1844 through absenteeism which, combined with a self-indulgent lifestyle and increasing debts, forced him into exile in Scotland where, as an alcoholic, he died of broken health aged 58.

In contrast to the wild Maxwell, naturalists in Northern Ireland were a more sedate and collected lot, reflecting a society steeped in Protestant ethics and moral sternness. However, Northern Ireland was about to experience a period of great excitement and ebullience: the golden age of natural history, dominated by the zoologist William Thompson, was just behind the door.

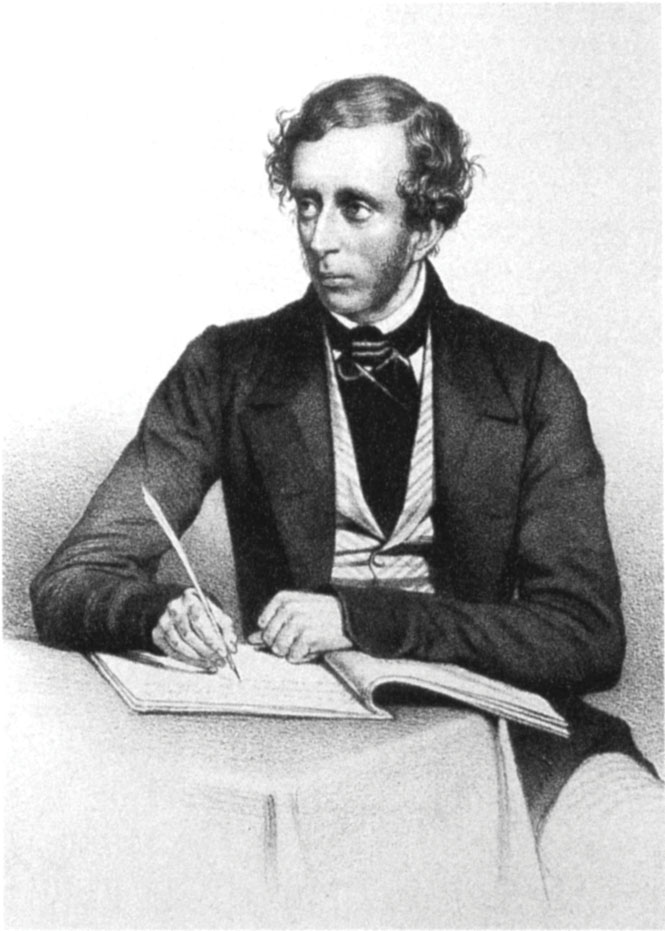

Born into one of the famous Belfast families of linen-makers, Thompson (1805–52) devoted his life to zoology, spurning the loom and the spinning jenny. Thompson’s magnum opus was The Natural History of Ireland.9 The first three volumes were on birds and were published in 1849, 1850 and 1851, before his untimely death in 1852, aged 47. He had intended to produce several more volumes to include all the remaining fauna, but only left a very incomplete manuscript. In accordance with Thompson’s will it fell upon Robert Patterson (1802–72), another eminent Belfast naturalist from a mill furnishing family, and James R. Garrett (1818–55), a Belfast solicitor and keen naturalist, to edit and publish this manuscript, which came out as a fourth variegated volume in 1856. Garrett was responsible for the mammals, fish and reptiles while Patterson handled all other groups. The production of the work must have been fated, for Garrett died before the book was printed. The information contained in the first three bird volumes is of such high standard – due to the accuracy of Thompson’s observations and those of a network of correspondents – that it is still interesting and valuable today.

One of the greatest tragedies of Irish natural history was the premature death of Belfast naturalist William Thompson aged 47.

While Thompson had been labouring away on his bird volumes he realised the need for a much smaller and inexpensive book for the general reader. The necessity was met by The Natural History of the Birds of Ireland (1853)82, written by his friend John Watters (fl. 1850s). A small, almost whimsical, Victorian production, laced with occasional romantic poems, it also contains hard facts on the habits, migrations and occurrences of the 261 listed species – a good antidote to Thompson’s weighty tomes.

Another fine zoologist from Northern Ireland, considered to be one of Europe’s greatest entomologists, was Alexander Henry Haliday (1806–70), a contemporary and friend of Thompson.83 A graduate in law, he never practised and managed the family’s estates in Co. Down, but he was more interested in entomology. He was highly cultured and an able linguist, a facility that allowed fruitful intercourse with continental entomologists. He published 75 entomological papers, including descriptions of several species new to science. He also contributed to Curtis’s British Entomology (1827–40) and other books.83

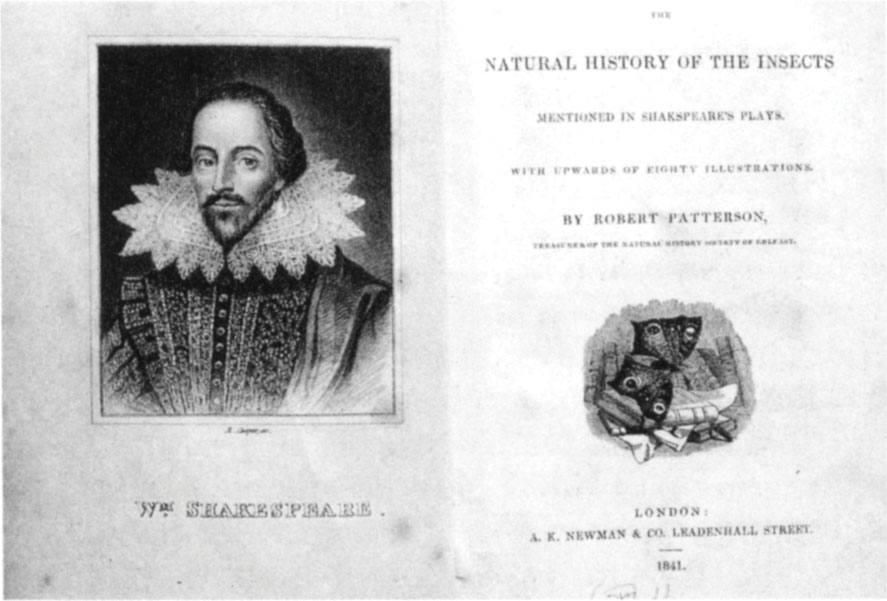

The Patterson family of Belfast were another force in the study of natural history. The first Robert Patterson (1802–72) was an accomplished naturalist who was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in recognition of this services to zoology. He authored the offbeat Letters on the Natural History of Insects Mentioned in Shakespeare’s Plays with Incidental Notes on the Insects of Ireland (1838), as well as several more traditional books including Introduction to Zoology for the Use of Schools (1845) and First Steps in Zoology (1848).84,85,86 His second son, Robert Lloyd Patterson (1836–1906), a keen student of all the zoological facets of Belfast Lough, wrote Birds, Fishes and Cetacea commonly frequenting Belfast Lough (1880)87, which drew upon a series of papers he read to the Belfast Natural History and Philosophical Society (BNHPS). Another Robert Patterson (1863–1931), grandson of the first one, specialised in ornithology but wrote very little, concentrating his natural history interests in playing a leading role in the Belfast Naturalists’ Field Club and the BNHPS.

Interest in birds was gathering momentum, though not always benevolent in spirit. Shooting and killing was much in vogue in the 1850s and Ralph Payne-Gallwey’s The Fowler in Ireland (1882)88 was a practitioner’s guide on how to shoot and trap wildfowl. It contained advice on how one could massacre birds by the hundreds by slowly paddling a punt equipped with a gun, mounted like a horizontal artillery piece, across muddy estuarine ooze towards unsuspecting flocks. Netting of plovers and other bird-catching tricks were described together with natural history accounts of the more valued quarry species. A more gentle bird book, with an evangelical flavour, produced by a school teacher, the Rev. Charles Benson (1883–1919) was Our Irish Song Birds (1886)89, which, according to Praeger, was ‘written with charm and understanding, worthy of a true naturalist’.

The migration of birds had long fascinated ornithologists. Despite a call by J. D. Salmon in 1834 for a chain of coastal observatories in Britain the initiative came from the Continent. In 1842 the Belgians attempted the observation of ‘periodic phenomena’, of which birds were a small part; then in 1875 the German bird watchers were organised into a massive scheme for recording the seasonal movements of migrating birds. In 1879 a pilot scheme was put into operation in Britain by the naturalists J. A. Harvie-Brown and John Cordeaux who had the bright idea of relying on the ready-made network of lighthouses and lighthouse keepers. Special recording forms were despatched to over 100 such coastal beacons and the experiment was a success.

Robert Patterson successfully quarried the zoological curiosities of the insects mentioned by Shakespeare and turned his endeavours into a charming and erudite book.

The following year, under the sponsorship of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, the scheme was refined and extended to Ireland. The Irish naturalist Richard Manliffe Barrington (1849–1915) set up the project, enlisting single-handedly all the lighthouse keepers in the country. Another member of the landed gentry and a contemporary of Henry Chichester Hart, Barrington was born and lived at the family property at Fassaroe, Co. Wicklow. He possessed remarkable energy and enthusiasm for natural history. With the encouragement of his mentor, Alexander Goodman More, Barrington undertook several botanical expeditions to west coast islands, Midland lakes and Benbulbin, Co. Sligo and for the purpose of his ornithological work he visited most Irish islands. He is probably best-known for his work on bird migration. From the observations of the lighthouse keepers, Barrington gathered a vast amount of information on bird migrations and movements, much of it new and exciting (see here). He painstakingly compiled all the raw data and brought them together into a fat, information-packed tome The Migration of Birds as observed at Irish Lighthouses and Lightships (1900). The book is a particularly important reference source for Irish ornithologists as, unlike most other bird books, all the raw data is published in full, turning the book into a rich ornithological database.90

Barrington, Richard John Ussher (1841–1913) and Robert Warren (1829–1915) comprised an ornithological triumvirate of probably the most gifted bird watchers ever seen in Ireland. In 1890 the three had planned together with More to write a much needed sequel to Thompson’s great work on birds published nearly 50 years earlier. New data had been gathered, especially on species in the process of becoming extinct or undergoing distributional changes, and it was clearly time for a new work. But Barrington was over-committed to his migration studies and unable to assist, More was suffering from ill health – he died in 1895 – and Robert Warren, in the words of Praeger ‘did not feel himself sufficiently equipped for so wide an undertaking’ so the task fell upon Ussher who became the ‘real’ author of The Birds of Ireland (1900).91