Полная версия

Collins New Naturalist Library

The wild, weary sea reposes and the speckled salmon leaps.

Over every land the sun smiles for me a parting greeting to bad weather.

Hounds bark, stags gather, ravens flourish, summer’s come.’

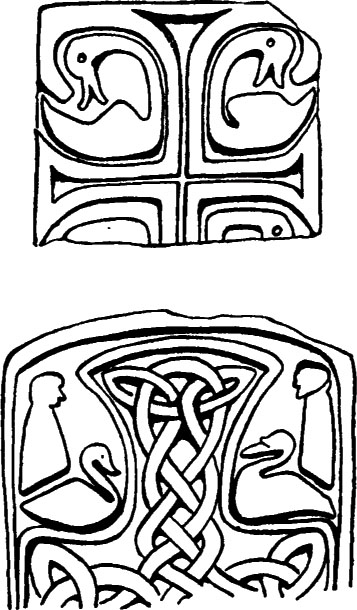

Carvings (c. seventh to eighth centuries) on slabs, Inishkeel, Co. Donegal.

Hunting scene (c. 790 AD), Bealin Cross, Co. Westmeath. From F. Henry (1965) Irish Art in the Early Christian Period (to 800 AD). Methuen & Co. Ltd., London.

A limited analysis of some ten of these early nature poems published by Jackson7 and Greene & O’Connor1 revealed that of 33 references to mammals, 19 were of (red) deer, stags, hinds and fawns, with many references to the stag’s roaring and bellowing.8 Next in occurrence were swine and boars (five mentions each) followed by three for badgers, two each for wolves and foxes and one each for the otter and seal (grey or common). Of the feathered creatures, the blackbird is cited most frequently (nine mentions) followed by four for the cuckoo and three each for the crane, heron and ducks. There are two references to a ‘woodpecker’, a species no longer resident in Ireland. Trees feature prominently with most citations being of the oak (six mentions), followed by yew (four) and three each for hazel, rowan and apple. Birch and ash carry two references. Hazel nuts were obviously of great significance, judging by the frequent references to them. Acorns and sloes were the next most noted. Of the plants and wildflowers mentioned, water-cress was the most prominent, followed by ivy, bracken, cottongrass, yellow iris, honeysuckle, marsh pennywort and saxifrage. The monk’s culinary interests were reflected by references to wild garlic, fresh leeks and wild onions.

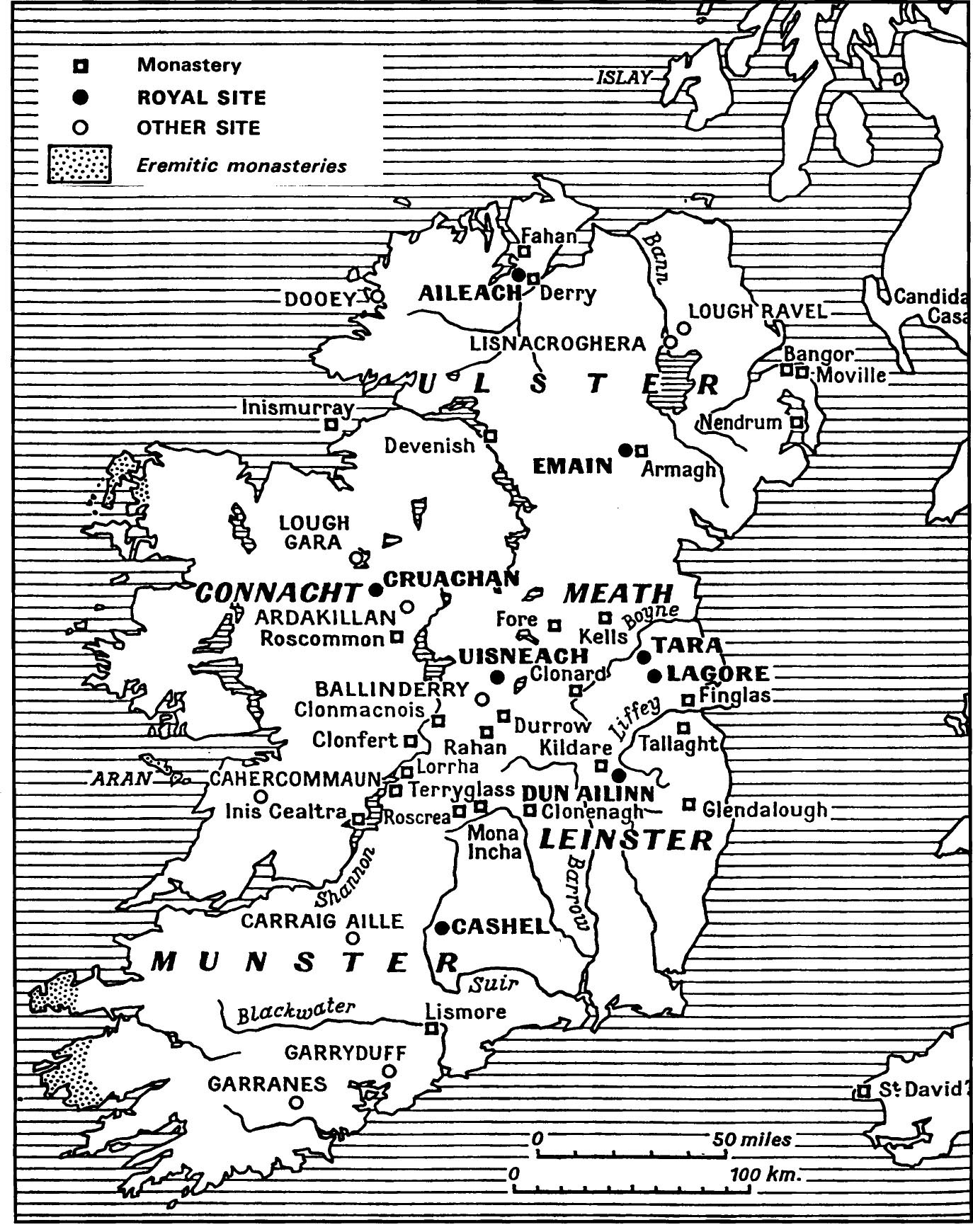

What do these early nature poems tell us about the natural world of Ireland as seen by the monks about 1,150 years ago? Firstly, the location of the observers determined their commentary and, contrary to the general impression that they lived in the fastness of remote islands off the west coast, most monks resided in monasteries located in the Midlands. Their poetry conjures up an auspicious mix of woodlands, pastures, lakes and rivers. Those religious men dwelled in a much richer and more biologically diverse environment than today’s, populated by several large mammals and bird species which subsequently became extinct. Red deer were clearly widespread and frequent due to more extensive deciduous woodland cover (of which the Irish red deer makes a greater use than its European counterparts). Also present in these woods were wolves and wild boars, not yet exterminated by man.

The descendants of the wolves from the early Christian period had mostly disappeared by 1700 but struggled on until 1786, when the last specimen was exterminated in Co. Carlow. Wild boar were formerly the most abundant of wild animals of Ireland. Their bones were found associated with the first known human settlers in Ireland some 9,000 years ago. According to Thompson9 they continued to be plentiful down to the seventeenth century, but their date of extinction is not known nor is it recorded when they were last seen. Robert Francis Scharff (1858–1934), Keeper of the Natural History Museum, Dublin, from 1890 until 1921, believed that the degenerate wild pigs seen by Giraldus Cambrensis during the late twelfth century were descended from domesticated stock introduced by the first Neolithic farmers some 6,000 years ago, but that also present with these feral pigs were descendants of the old European wild boar which he claimed had been present in prehistoric Ireland.

Eagle. Book of Durrow (late eighth or early ninth century). (The Board of Trinity College, Dublin).

The corncrake and wild swans, distinguished by their striking and unmistakable calls, impressed the monks as summer and winter visitors respectively to earn several citations in the early poetry. Eagles in those days bred on the cliffs in remote areas: the white-tailed eagle survived in coastal regions in decreasing numbers until the early twentieth century, when it completely died out, and the golden eagle hung on until 1926 then remained extinct apart from a pair from the Mull of Kintyre in Scotland that bred on the Antrim coast from 1953–60. Remains of the great spotted woodpecker found in two separate caves in Co. Clare indicate that they were present in the primeval woods. They may have persisted to the ninth century, as suggested by several references to them in the nature poems, but by the twelfth century they would appear to have become extinct. They too fell foul of the shrinking woodlands. In contrast to these unfortunate species, the descendants of the badger and otter, also featuring in the monks’ observations, have maintained thriving populations and remained symbols of the countryside.

Augustin, the first naturalist

One Irish monk living in the seventh century, known as Augustin, composed an interesting text in 655 which, unlike many others, survived because of a superficial confusion between him and his virtual namesake, St Augustine, Bishop of Hippo (354–430), the founding father of the Christian Church. The Hibernian Augustin was fortunate – and so are we – to have his text Liber de Mirabilibus Sanctae Scripturae embedded in the third volume of most editions of the great St Augustine’s works, notwithstanding the 200 years separating the two men. Without such an occurrence of editorial laxity it is doubtful whether the writings of the lesser Augustin would have survived for posterity.10

Principal monastic and other sites of AD 650–800. From F. Henry (1965) Irish Art in the Early Christian Period (to 800 AD). Methuen & Co. Ltd., London.

The central thesis of Augustin’s work was that God rested on the seventh day after all his work was done but that once creatio was completed the gubernatio of the Deity never ceased. The monk believed that mirabilia or miracles were not new creations but only certain unusual developments of the secrets of nature. He wrote of the miracles of the Bible, and questioned why terrestrial animals, unlike their aquatic relatives, were made to bear the brunt of the Deluge (they drowned whereas fish did not) and how the life of amphibious creatures such as otters and seals could be maintained during the same period when they needed dry land to sleep and rest on. In the chapter De recussu aquarum diluvii he wondered where the Deluge waters came from and went to. He observed the fluctuations of the sea, the inundationes et recessus Oceani, noting the daily tides, the fortnightly neap tides and spring tides that suggested to him the waxing and waning of the Deluge waters. He observed that the changes in sea level were so great that what were islands may have been part of the mainland at some stage and that these changes were of considerable significance regarding the animals found on islands.

Augustin reasoned that if the mainland and islands shared a common fauna they must have had former connections. Thus, some 1,200 years before eminent naturalists such as Alfred Wallace and Charles Darwin tackled the same issues, the monk had the first intuition of a land bridge between countries. St Augustine of Hippo had himself earlier pondered in De Cicitate Dei whether the remotest islands had been granted their animals from the stocks preserved throughout the Deluge in the Ark or whether those animals had sprung to life on the spot:

‘It might indeed be said that they crossed to the island by swimming, but this could only be true of those islands which lie very near the mainland, while there are others so distant that we fancy no animal could ever swim to them… At the same time it cannot be denied that by the intervention of angels they might be transported thither, by order and permission of God. If however they are produced out of the earth as at their first Creation, when God said “Let the earth bring forth the living creatures”, this makes it more evident that all kinds of animals were preserved in the ark not so much for the sake of renewing the stock as prefiguring the various nations which were to be saved by the Church; this, I say, is more evident if the earth brought forth many animals to islands to which they could not cross over.’11

The Irish Augustin focused the argument closer to home. Being familiar with the fauna of Ireland and knowing that much of it was common to Britain he asked the following question: ‘Quis enim, verbi gratia, lupos, cervos, et sylvaticos porcos, et vulpes, taxones, et lepusculos et sesquivolos in Hiberniam deveheret?’12 ‘Who indeed could have brought wolves, deer, wild (wood) swine, foxes, badgers, little hares and squirrels to Ireland?’ His statement is the first known written record of some of the quadrupeds present in the country during the mid-seventh century.

Giraldus Cambrensis: Topographia Hiberniae 1185

The next important text on Irish natural history came some 530 years later. The author was Giraldus de Barri, alias Giraldus Cambrensis, the grandson of Henry I. His family on his mother’s side were FitzGeralds, active in the Norman invasions of Ireland. Maurice FitzGerald, his uncle, was one of the principal leaders. Cambrensis’s first excursion to Hibernia was in 1183, a visit lasting less than a year. According to his treatise Expungnatio Hiberniae, the reason for his travel was ‘to help my uncle and brother by my council, and diligently to explore the site and nature of the island and primitive origin of its race’.

Topographia Hiberniae, which received its inaugural reading at Oxford in or around 1188,3 provides a remarkably interesting account of twelfth century Ireland, although the accuracy of its natural history has been questioned and dismissed by one naturalist as ‘an amalgam of fact, fibs and fantasy and much of it patently absurd. It is undoubtedly of much use but, from the scientific point of view, so apocryphal a document is not to be relied upon without supporting evidence.’13 Other naturalists have concentrated on the miracles and strange beliefs recounted, using them to discredit the whole text. For instance, Cambrensis talks about barnacle geese hatching from goose barnacles found clinging to floating logs in the sea. ‘They take their food and nourishment from the juice of wood and water during their mysterious and remarkable generation. I myself have seen many times with my own eyes more than a thousand of the small bird-like creatures hanging from a single log upon the sea-shore.’ Such miracles were in vogue, a convenient way of explaining mysterious phenomena and the substance of bestiaries. What about, for instance, the bended leg of the crane? Cambrensis explained that when on watch duty, the crane stood on one leg while clutching a stone in the other which would drop when the bird went to sleep, so that it would be awakened on the spot and could resume its watch. Not all of Cambrensis is as blatantly fantastical as this. Praeger sums it up when he says that Cambrensis ‘was a careful recorder, but credulous; and from his statements it often requires care and ingenuity to extract the truth’.2 Thus the reader has to disentangle strands of truth from strands of fiction, and make intelligent guesses – whereupon certain important points emerge.

In defence of Cambrensis’s flights of fancy, many writers on natural history, even well into the second millennium, also traded some equally extraordinary beliefs and myths. Another typical story is that of the vanishing birds, or ‘birds that do not appear in the winter-time’. To Cambrensis they ‘… seem … to be seized up into a long ecstasy and some middle state between life and death. They receive no support from food … and are wakened up from sleep, return with the “zephyr” and the first swallow.’ This is close to the misconceptions, persisting many centuries later, concerning the hibernation of swallows, which, it was postulated, spent the winter in estuarine muds. The large pre-migratory flocks congregating in the autumn, their wheeling over reed beds, their subsequent disappearance and mysterious re-emergence the following spring led many naturalists to believe that at some stage they buried themselves in the soft ooze. Such stories were trotted out into the late eighteenth century, even by such writers as Gilbert White (1720–93).14 If White could agree to such absurdities then Cambrensis will be partly forgiven for seeing birds in shellfish and slumberous cranes holding stones.

Topographia Hiberniae is presented in three parts: the position and topography of Ireland, including its natural history; the wonders and miracles of Ireland, and the inhabitants of the country. Cambrensis claimed that he used no written sources for the first two parts and so must have drawn mostly upon his own observations and notes, together with information provided by other people. As shown by his text, Cambrensis did not venture outside the neighbourhoods of Waterford or Cork on his first visit. On his second trip he travelled from Waterford to Dublin, possibly by the coastal route, and he probably visited Arklow and Wicklow. He saw both Kildare and Meath and almost certainly the River Shannon at Athlone, as well as Loughs Ree and Derg.15 In short, Cambrensis remained within the Norman-occupied areas where he would always be granted protection and succour. His commentary is thus biased towards the more fertile and amenable landscapes of Ireland.

The following analysis of the fauna of the time is based on the first version of the three known manuscripts copied from the original work by Cambrensis. This version dates from the twelfth century and is a copy in Latin, translated here by O’Meara.15 For Cambrensis, Ireland was a land ‘fruitful and rich in its fertile soil and plentiful harvests. Crops abound in the fields, flocks on the mountain and wild animals in the woods.’ However, the island was ‘richer in pastures than in crops, and in grass rather than grain’. As to the grass, it was ‘green in the fields in winter just the same as in summer. Consequently the meadows are not cut for fodder, nor do they ever build stalls for their beasts.’

Cambrensis went on to describe the soil, ‘soft and watery, and there are many woods and marshes. Even at the tops of high and steep mountains you will find pools and swamps. Still there are, here and there, some fine plains, but in comparison with the woods they are small.’ Swarms of bees ‘would be much more plentiful if they were not frightened off by the yew trees that are poisonous and bitter, and with which the island woods are flourishing.’ The rivers and lakes were rich in fish, especially salmon, trout and eels, and there were sea lamprey in the River Shannon. Three fish were present in Ireland that were ‘not found anywhere else’ – pollan, shad and charr – but other freshwater fish were ‘wanting’ – pike, perch, roach, gardon (chubb) and gudgeon. The same applied to minnows, loach and bullheads, and ‘nearly all that do not have their seminal origin in tidal rivers…’. They were nowhere to be seen.

Amongst the birds, Cambrensis noted that sparrowhawks and peregrine falcons were abundant, together with ospreys. He pondered why the hawks and falcons never increased their numbers as he observed that many young were born each year but few seemed to survive to adulthood, perhaps a hasty observation as he was hardly there long enough to pay close attention to population dynamics: ‘There is one remarkable thing about these birds, and that is, that no more of them build nests now than did many generations ago. And although their offspring increases every year, nevertheless the number of nest-builders does not increase; but if one pair of birds is destroyed, another takes its place.’ Eagles were as numerous as kites (harriers were often called ‘kites’ in ancient times), quail were plentiful, corncrakes innumerable, capercaillie nested in the woods (by 1800 they had become extinct) and only a few red grouse occupied the hills. ‘Cranes’ were recorded as being so numerous that one flock would contain a ‘hundred or about that number’. Barnacle geese were seen on the coastline while rivers had dippers, described by Cambrensis as a kind of kingfisher: ‘they are smaller than the blackbird, and are found on rivers. They are short like quails.’ True kingfishers were also present on the waterways. Swans (almost certainly whooper or Bewick’s) were very plentiful in the northern part of Ireland. Storks were seldom observed and were the ‘black kind’, but were in fact almost certainly the white or common stork, in view of the extreme scarcity of the black stork in Ireland. There were no black (carrion) crows, or ‘very few’. Crows that were present were ‘of different colours’ – i.e. hooded crows – and were seen dropping shells from the air onto stones, a behaviour often witnessed today. Partridges and pheasants (introduced during Elizabethan times) were absent, as were nightingales (the first Irish record was a migrant at Great Saltee, Co. Wexford, in 1953) and magpies. The historian Richard Stanihurst also observed in 1577 that ‘They lack the Bird called the Pye.’16 All magpies in Ireland today have descended from a ‘parcel of magpies’ that suddenly appeared in Co. Wexford about 1676.17

Floral motifs on cross (c. twelfth century) at Glendalough, Co. Wicklow. From F. Henry (1970) Irish Art in the Romanesque Period 1020–1170 AD. Methuen & Co. Ltd., London

Corroborative evidence for some of Cambrensis’s bird records comes from the remains of bird bones found in a lake dwelling, or crannóg, on a small island in the middle of a shallow lake at Lagore, near Dunshaughlin, Co. Meath. The crannóg dates from ad 700–900 with no evidence of occupancy after the Norman invasion of the twelfth century. Over one thousand bird bones were found during an excavation of the site and most were identified by Stelfox of the Natural History Museum, Dublin.18 The following species, relevant to Cambrensis’s text, were recorded: sea-eagle (four bones), barnacle goose (202 bones or fragments), whooper swan (19 bones), Bewick’s swan (9 bones), corncrake (one bone), crane (25 bones or portions of bones representing cranes of three different sizes) and heron (one skull and one beak). From these last two findings it might be concluded that Cambrensis was right about the abundance of cranes in Ireland, and that he was not confusing them with herons.

While now long extinct, cranes abounded in Ireland during the fourteenth century according to the text Polychronicon written by Ranulphus Higden (c.1299–c.1364), a monk from Chester, England.19 Their bones have been found in the Catacomb (five bones in the lower stratum of cave material, indicating the antiquity of the material) and Newhall Caves (one bone in the upper stratum), Co. Clare, dating back to prehistoric times.20 They were also a dietary item for the Late Bronze Age people of Ballycotton, Co. Cork.21

Animal bone evidence from earlier human settlement sites has shown wild boar, pigeons, duck, grouse, capercaillie and goshawk – another woodland species – at Mount Sandel, over looking the lower reaches of the River Bann, Co. Derry, and dating from some 9,000 years ago. Goshawk bones have also been found at a later Mesolithic site on Dalkey Island, Co. Dublin, and at the Early Bronze age site of Newgrange, Co. Meath. Further south at Boora Bog, near Tullamore, Co. Offaly, human food remains, contemporary with Mount Sandel, included pig, red deer and hare.22

Red deer stags were noted by Cambrensis as ‘not able to escape because of their too great fatness’ whereas the wild boars ‘were small, badly formed and inclined to run away’. Hares were present: ‘but rather small, and very like rabbits both in size and in the softness of their fur’. When put up by dogs ‘they always try to make their escape in cover, as does the fox – in hidden country, and not in the open’. However, when talking about ‘hares’, Cambrensis may have been describing wild rabbits – the behaviour reported is more typical of rabbits than hares – which were introduced by the Normans at about the time of Cambrensis’s visits. Pine martens occurred commonly in the woods, where they were hunted day and night, and badgers, according to the Welshman, frequented ‘rocky and mountainous places’. Cambrensis states that the following were absent from Ireland: moles, wild goats, deer, hedgehogs (later recorded by the historian Roderic O’Flaherty in 1684), beavers and polecats. Mice, on the other hand, were ‘infinite in numbers and consume much more grain than anywhere else’. There were no ‘poisonous reptiles’, nor ‘snakes, toads or frogs, tortoises or scorpions’.

This last statement has repeatedly been taken by naturalists as evidence that there were no native frogs in Ireland, leading to much debate about the status of the species. The controversy concerning the history of the frog is discussed in Chapter 2. Cambrensis also came across lizards, presumably viviparous lizards, the only lizard in Ireland. This was a politically injudicious observation, for St Patrick was supposed to have done a thorough job in banishing not only all snakes but also all reptiles. Cambrensis was, in fact, blunt in dismissing St Patrick’s alleged role. ‘Some indulge in the pleasant conjecture that St Patrick and other saints of the land purged the island of all harmful animals. But it is more probable that from the earliest times, and long before the laying of the foundations of the Faith, the island was naturally without these as well as other things.’ Already in the third century, before St Patrick is supposed to have wielded the crozier, Caius Julius Solinus, the Roman compiler of the early third century, had commented in Polyhistor – which drew from the work of Pliny the Elder – on the absence of snakes:23

‘Illic [in Hibernia] nullus anguis, avis rara, gens inhospita et bellicosa.’

‘In that land there are no snakes, birds are few and the people are inhospitable and war-like.’

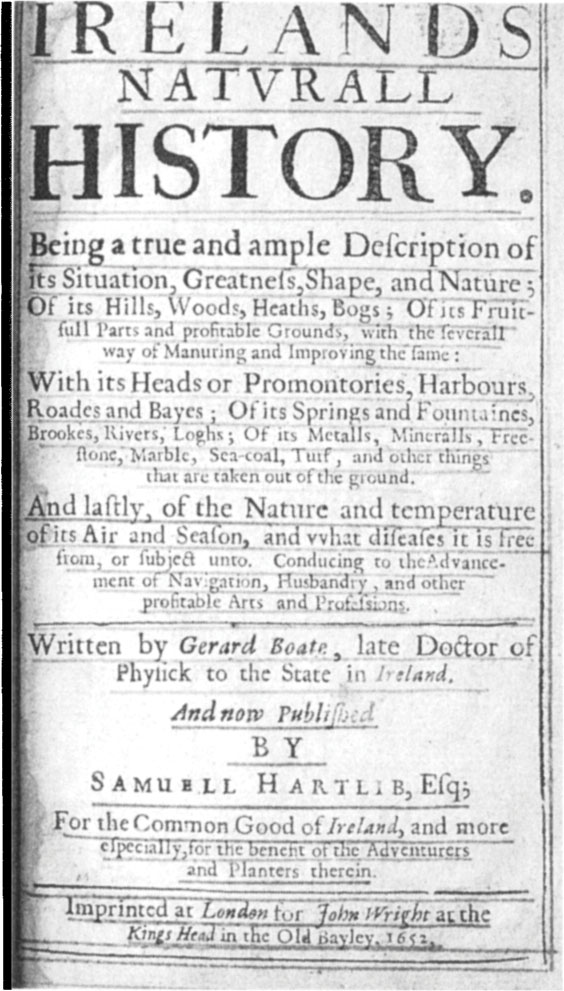

Gerard Boate: Irelands Naturall History 1652

Irelands Naturall History was the first regional natural history in the English language, written essentially for the benefit of adventurers and planters who were thinking of settling in Ireland during the mid-seventeenth century. Its compiler and author was a Dutchman by the name of Gerald Boate (1604–49). He and his brother Arnold were involved with the formation in the summer of 1646 of the Invisible College, a body of Anglo-Irish intellectuals revolving around the Boyle family of Lismore Castle, Co. Cork. The formation of the College was initiated in London by the scientist Benjamin Worsley and his brilliant 19 year-old intellectual friend Robert Boyle as a means to propagate their conception of experimental philosophy amongst their immediate friends and colleagues. These included the Boates and Samuel Hartlib, a Pole and puritan intellectual resident in London – later the publisher of Irelands Naturall History,24 Gerard Boate was a physician and he attended to the health of Robert Boyle and his sister Katherine, later Lady Ranelagh, herself a patron and driving force behind the Invisible College.24 The Boates were anti-authoritarian both in natural philosophy and medicine (they had several conflicts with the College of Physicians) and were keen supporters of Baconian natural history – both good recommendations for membership of the Invisible College.

Title page of the first edition of Boate’s Irelands Naturall History (1652).

The College played an important role in ushering into Ireland the new natural philosophy that was arising in Europe in the wake of work by Galileo, Mersenne and Descartes.25 It was an assembly of ‘learned and curious gentlemen, who after breaking out of the civil wars, in order to divert themselves from those melancholy scenes, applied themselves to experimental inquiries, and the study of nature, which was then called the new philosophy, and at length gave birth to the Royal Society.’26 The Royal Society was formed in London during 1662.