Полная версия

Collins New Naturalist Library

Benbulbin, Co. Sligo. An uplifted carboniferous limestone plateau with dramatic cliffs, the home of many rare arctic-alpine plants.

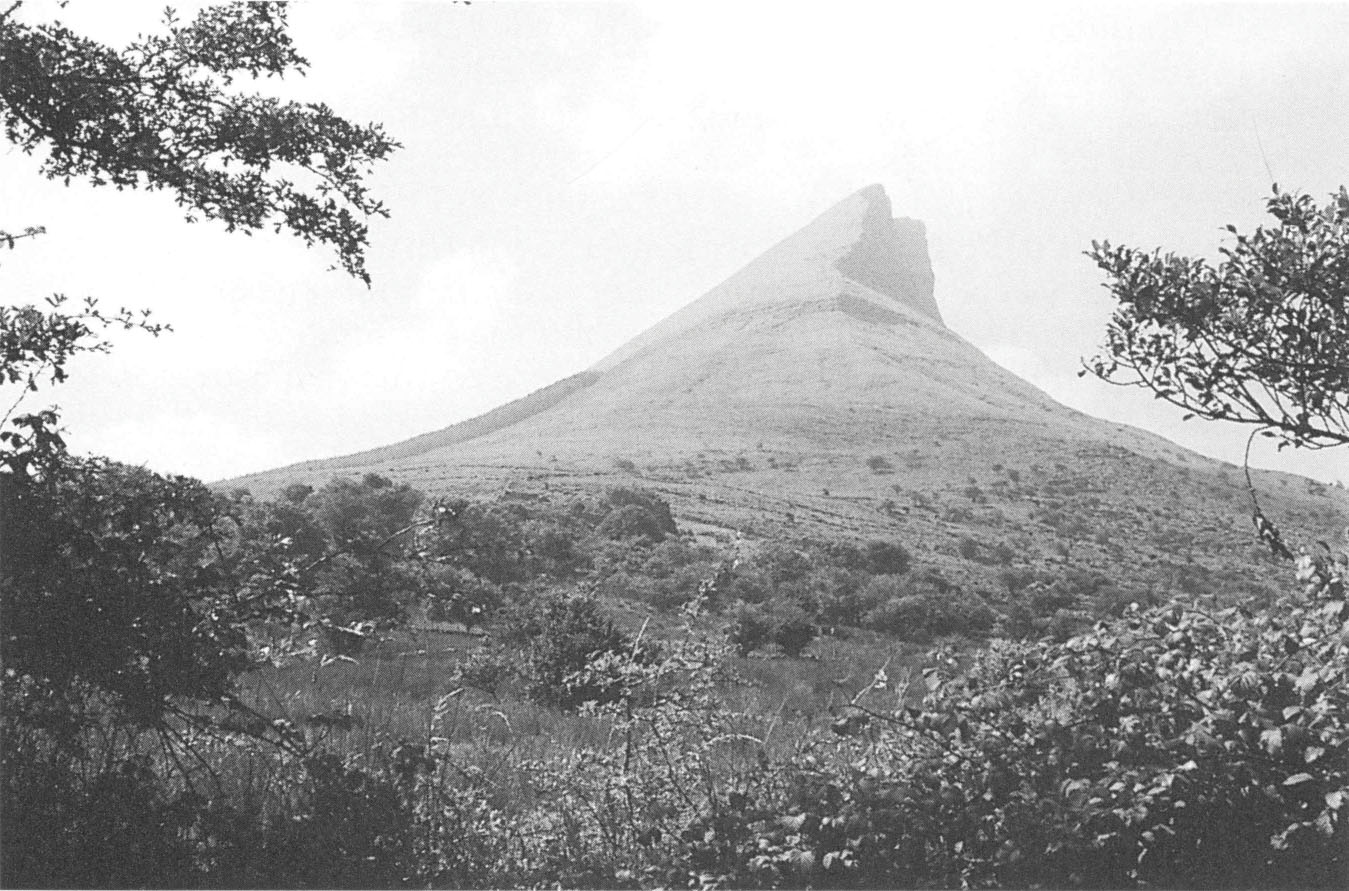

Benwiskin (514 m), Co. Sligo, as dramatic as the nearby cliffs of Benbulbin (F. Guinness).

The best known part of the Benbulbin mountain range is the spectacular western spur where the eponymous summit rises to 526 m with its high, sculptured profile. Two large, cliff-walled valleys, each with a lake – Glencar Lough in the south and Glenade Lough in the east – bisect the two mountain lobes and provide topographical diversity to an already very dramatic landscape. The Benbulbin area, extending from Co. Sligo to Co. Leitrim, is so extensive that it would take a botanist at least seven days, working at a feverish pitch, to do the place justice. There are, however, two ‘hot spots’ for the arctic-alpines and alpines.

The first area is the cliffs of Annacoona in the Gleniff Valley, guarded at the northwest entrance by Benwiskin (514 m) which rises to a remarkable pinnacle, like the Matterhorn, surveying the landscape. The Annacoona cliffs face northeast, overlooking the great cirque of Gleniff, gouged out by a glacier. On a still summer’s day the croaking of ravens, rolling around and playing aerobatics along the steep cliffs, the occasional shrieking of a peregrine and the bleating of sheep are the only sounds in this otherwise silent valley. On the cliffs at Annacoona the arctic-alpine flora starts from an altitude of about 244 m upwards. The rarest species is fringed sandwort which has its home here on the upper sections of the limestone cliffs, between 300 and 550 m. This small and deceptively dainty, white-flowered and slightly hairy perennial is a member of the Caryophyllaceae or chickweed family and was first discovered by the eminent Welsh antiquarian and natural historian Edward Lhwyd on one of his visits to Ireland in 1699. He recounted the discovery in a letter to Tancred Robinson, a great friend of the British botanist John Ray: ‘In the same neighbourhood on the mountains of Ben Bulben and Ben Buishgen, we met with a number of the rare mountain plants of England and Wales, and three or four not yet discover’d in Britain.’28 Irish specimens of fringed sandwort were assigned to the special endemic subspecies Arenaria ciliata subsp. hibernica by Ostenfeld & Dahl in 1917 who also separated off two other subspecies, A. c. pseudofrigida found in arctic Europe and Arctic sandwort A. c. norvegica found in Shetland, arctic Europe and America.29 There is one record of A. c. norvegica from the Burren in Co. Clare but it has never been rediscovered despite repeated attempts by many botanists. Endemic species, or subspecies, are restricted to a specific geographic region and have evolved the differences that separate them from their close relations due to their isolation, or in response to soil or climatic conditions.

Annacoona is the only known Irish station for alpine saxifrage, first discovered here by the botanist John Wynne in 1837. Its leaves are purple underneath and it has a very hairy inflorescence with white petals and reddish sepals. Within the Benbulbin area alpine meadow-rue is also confined to Annacoona. Amongst the species listed by Praeger found on the cliffs and escarpments, the following occur in profusion:3 alpine scurvygrass, hoary whitlowgrass, mountain avens, yellow saxifrage, mossy saxifrage, brittle bladder-fern, green spleenwort, limestone bedstraw and common milkwort. More locally abundant are lesser meadow-rue, moss campion, purple saxifrage, upland enchanter’s-nightshade, mountain sorrel, tea-leaved willow, blue moor-grass, holly fern, beech fern and Irish eyebright. Raven in Mountain Flowers writes that the Benbulbin eyebrights he saw on his visit resembled some, but not all, of the specimens of Euphrasia lapponica he had seen in isolated populations in northern Scandinavia1. The following species are rare: Welsh poppy, wood vetch, several hawkweeds including Hieracium hypochoeroides, cowberry, alpine bistort, dwarf willow, juniper, stiff sedge, maidenhair fern, large thyme and alpine meadow-grass (found only here and on the Brandon Mountain, Co. Kerry). Isolated trees or small clumps of them, firmly rooted in the vertical cliffs, are a curious sight – rock whitebeam, wych elm and yew are all present, only ever to be touched by birds and flying insects.

The other interesting place for arctic-alpines and alpines is a section of the north-facing cliffs some 5 km northeast on the Tievebaun Mountain, Co. Leitrim. The cliffs are northwest of Glenade Lough. The exciting section extends for about 800 m at an altitude of 213–366 m. Many species already growing at Annacoona are found here, together with the chickweed willowherb, a unique speciality of these precincts. First discovered here by R.M. Barrington and R.P. Vowell in 1884, it is a low, small, creeping, almost hairless willowherb with runners above the ground. The flowers are purplish-pink and the seed pods turn red when ripe. Partial to streams and wet places, especially dripping rocks, this willowherb has two sites at Glenade. The first is a wet cliff, where 100 plants grow in an area of about 25 m2. The second occurs along a small stream where a 30 m stretch accommodates about 70 plants. Also at Glenade, on an inaccessible vertical cliff, is the northern rock-cress, at one of only two locations in Ireland, the other being a site in the Galty Mountains, Co. Tipperary.16 This rock-cress is a small, slightly hairy plant with lobed lower leaves and small white, sometimes lilac flowers born on flowering stems some 8–25 cm tall. The seeds are carried in a long flattened pod. Golden saxifrage is here, found in wet spots on the cliff between 215 and 366 m. It is low and loosely tufted perennial with spreading and creeping stems that are square. The flowers are small, yellowish and without petals. Wych elm and rock white-beam grow on the cliff face wherever they can get a toehold.

One curious feature of Benbulbin’s flat top, as previously mentioned, is its covering by a thick blanket of peat bog, with all the attendant peatland plants. Where the underlying limestone pokes up through the vegetable skin a calcicole flora develops including several alpine species. During the colonisation process several species of mosses, especially Breutelia chrysocoma, settle on the limestone pavement, thrive and proliferate, and they soon produce layers of humus which can then be colonised by the seeds of heather and other ericaceous species. The new arrivals draw most of their nutrients from the acidic moss humus rather than from the limestone below by ensuring that their roots grow initially upwards or horizontally.30 Gradually the bog builds up, becoming more and more acidic with time, and the plants then exist on whatever nutrients they can draw from their own mounting pile of peat humus plus those that fall out of the sky with the rain.

Slieve League, Co. Donegal

‘One of the finest things of its kind’ was how Praeger described the mountain of Slieve League which brutally confronts the Atlantic Ocean at the end of the southwestern promontory of Co. Donegal. Made up of very old rocks – ancient schists, gneisses and quartzites laid down some 500 million years ago and then thrust up in the Caledonian upheavals – Slieve League rises to 595 m at its summit. It is essentially a quartzite peak, with some Carboniferous sandstone and even less limestone occurring on the summit. Like the Benbulbin mountain range it was almost certainly ice-free in days of glacier supremacy, a haven for arctic-alpine plants and other refugees. The southern side of the mountain has been truncated by the continual pounding of the Atlantic to form some of the most impressive cliffs in Europe. At sunset, the cliff structures, made mainly of quartzite and gneiss, glint and reflect the light in a way that signals their long and tortured history. On the north side of the mountain more cliffs plummet from about 460 m, equally dramatically, down to the dark and seemingly sinister Lough Agh that sits at an altitude of 245 m. Starting from the village of Teelin to the southeast, one of the best walks in Ireland can be had by ascending the summit including a bracing passage along a knife-edge ridge, appropriately named ‘One Man’s Path’. The northern precipice is one of the finest sites in Ireland for arctic-alpine plants and has attracted the attention of many distinguished botanists and naturalists for more than a hundred years. The number of arctic-alpine species is greatest here, and progressively declines southwards down the west coast and even more rapidly as one moves southwards along the east coast of Ireland.

Not only is the total number of arctic-alpine and alpine species on the north-facing cliffs of Slieve League the largest in the country but there are more species here than in any other similar habitat of comparable size in Ireland. Hart, who lived in Donegal and was at leisure to climb up and down Slieve League, reported many in his Flora of the County Donegal,31 thus supplementing earlier work.32 The species, listed again later by Praeger in The Botanist in Ireland include bearberry, green spleenwort, stiff sedge, mountain avens, dwarf juniper, alpine clubmoss, mountain sorrel, alpine bistort, holly fern, dwarf willow, alpine saw-wort, yellow saxifrage, purple saxifrage, starry saxifrage, roseroot, lesser clubmoss and alpine meadow-rue.

Slieve League cliffs, Co. Donegal.

H. J.B. and H.H. Birks, together with Ratcliffe, visited Slieve League in September 1967 when they explored the shattered and gully-seamed cliff above Lough Agh.33 The most interesting site here is a north-facing outcrop of calcareous schistose rocks extending for about 91 m at an altitude of 400–460 m. They added the brittle bladder-fern and mountain everlasting to the list for the area as well as recording 29 bryophytes of interest. Most of these are characteristic of calcareous rocky outcrops and are generally widely distributed in Ireland, apart from the liverwort Gymnomitrion concinnatum. Two mosses were of particular interest. One was the rare oceanic Leptodontium recurvifolium, providing a link between its previously known Irish localities in Kerry, Galway and Mayo and the western Scottish Highlands. The other, Orthothecium rufescens, also provided a connection between the Scottish Highlands and its previously known Irish sites on the Carboniferous limestones of Sligo and Leitrim, and the Burren, Co. Clare.

The basaltic plateau of Counties Derry and Antrim

The upland plateau that forms most of Co. Antrim and three-quarters of eastern Co. Derry is made up of volcanic outpourings that settled out over the landscape in level sheets of lava as recently as 65 million years ago. This is, therefore, the newest part of Ireland. The northern edges of the plateau from Lough Foyle in the north to Belfast Lough in the east are scarped with some impressive cliffs. Where the basalt cooled slowly it split up into a series of vertically jointed polygonal columns which appear in their most dramatic form at the Giant’s Causeway.

Basalt rocks are composed of 45–55% silica and are classified as basic rocks. They also contain lime, and disintegrate through weathering to produce a comparatively fertile clayey soil, rich in calcium carbonate, providing an attractive environment for many arctic-alpine and alpine plants. Binevenagh, Co. Derry, in the northwestern part of the plateau, looks out over the flat and sandy coastline of Magilligan. Binevenagh has high and dramatic north-facing cliffs, standing over a jumbled, tortured mass of land slips, fallen rock and other debris. These cliffs are famous as one of the best locations in Northern Ireland for a wide range of arctic-alpine and alpine plants growing at uncharacteristically low levels. In fact, the interesting species reported here include two plants not found anywhere else in the province: purple saxifrage, growing sparingly between 275 and 330 m, and moss campion. The moss campion, noted here for its profuse growth and for having flowers that range in colour from deep purple to white (rare), is especially abundant around the screes above Bellarena and at the eastern end of the cliffs. Other species present are alpine scurvygrass (not seen recently34), hoary whitlowgrass, mountain avens on the cliffs at 240–335 m, limestone bedstraw, dwarf willow and juniper.

Some 58 km further southeast on the high Garron plateau, sitting behind Garron Point on the Antrim coastline, there is an extensive tableland of bare and desolate blanket bog at an elevation of 305–366 m. The bog is deep and wet with many pools and small lakes. Growing here is the rare marsh saxifrage which has bright yellow, often red-spotted, flowers. It was formerly recorded from eight sites in Ireland, spread though six counties. Since 1970 it has only been recorded at this location, at three sites close together on the Nephin Beg Range, Co. Mayo, and at a mineral flush in the wet blanket bog near Bellacorick, Co. Mayo. It is also in decline in Britain.16,35 On the Garron plateau it grows at a mineral flush, fed by a spring arising from the basalt rocks, and surrounded by the moss Drepanocladus revolvens. Other associated species are daisy, bogbean, selfheal, sharp-flowered rush, bog-sedge, glaucous sedge and large yellow sedge.

Garron Bog is also the home of two rare alpine sedges that grow at about 300 m in the area southeast from the Falls, in the upper Glenariff River to Trosk, high above the village of Carnlough. The few-flowered sedge occurs fairly commonly over a large area – at about 20 stations – extending over at least two 10 km squares of the national grid. It is a loosely tufted, creeping and mat-forming sedge with a shortish stem, up to 25 cm high and bluntly three-sided. The flowers are on a single bractless spike. First discovered by the Rev. H. W. Lett in 1889, this is one of only two Irish locations, the other being a watery peatland site on the edge of the Red Moss of Kilbroney, a somewhat miniature Garron plateau, at an altitude of 340 m on the Mourne Mountains behind Rostrevor, Co. Down.34 The other sedge is the tall bog-sedge – first found by Miss Elinor D’Arcy in 1901 when she was only 11 years old – well-established on Garron Bog at several sites near pools, where it grows with Sphagnum moss and other sedges. Its leaves are 2–3 mm wide and its stems reach up to 40 cm. Until 1981 the Garron site was thought to be the only place where it grew in Ireland but then another location was discovered in an upland blanket bog in Co. Tyrone where it was growing on the west side of Lough Carn. It was later discovered in 1985 at Mill Lough, near Lough Fea and also at Lough Ouske, Co. Derry.34

Sperrin Mountains, Co. Tyrone, manifesting erosion of the shallow peats.

Sperrin Mountains, Counties Tyrone and Derry

The Sperrin Mountains are made up of old rocks, mainly schists and gneisses in the northern parts, with Old Red Sandstone and a little limestone in the southern sections. The area is covered by upland blanket bog with a series of summits each rising to the region of 610 m. This is where the cloudberry was first found in 1826 by Edmund Murphy and Admiral Jones. It was growing in a single patch on a north-facing slope of wet blanket peatland at an altitude of about 533 m, west of the Dart Mountain summit. Today it flourishes almost submerged in the surrounding vegetation.36 A member of the rose family, it is a small, blackberry-like plant with a white flower – a low, downy, creeping perennial spreading vegetatively by rhizomes. It is described as a ‘shy flowerer and fruiter’ in Ireland as it seldom, if ever, sets fruit. This is thought to be due to the overwhelming presence of plants of a single sex – the stamens (the male organ consisting of a filament and a pollen sac called the anther) usually set in a ring outside the flower centre, and styles (columns of filaments arising from the female organs terminating in the stigma receptive to pollen), usually located within the ring of anthers in the flower centre, are borne on separate flowers that are located in many separated single sex patches.

The Mourne Mountains, Co. Down

The Mourne Mountains stand up as a group of granite hills in south Co. Down with some flanking Silurian rocks. Carlingford Lough lies to the south. Many summits exceed 600 m, and the highest point is Slieve Donard at 850 m. Amongst the granite outcrops are some impressive cliffs and dramatic pinnacles that have originated by longer periods of weathering of the rock. Blanket bog covers the uplands and where the Silurian slates have been worn down by the weather, producing a richer soil, more interesting plants occur. The arctic-alpine and alpine flora is disappointing – already we are on the eastern coast of Ireland – and consists of the usual run-of-the-mill species. Amongst the plants of the higher ground, recorded by Praeger, are alpine saw-wort, dwarf willow, cowberry and alpine clubmoss. Lower altitudes host starry saxifrage, roseroot and the parsley fern. On the high cliffs of Slieve Bignian and Eagle Mountain Praeger recorded the very rare native form of the rosebay willowherb.3 It was still at the latter site in 1985 at an altitude of 455 m.34 Also at the high altitudes are the brittle bladder-fern and the stag’s-horn clubmoss with its long and decorative ‘antlers’.

The Galty Mountains, Counties Tipperary and Limerick

The Galtys were thrust up during the dramatic Hercynian earth movements some 300 million years ago that were also responsible for creating the mountain ranges of the southwest of Ireland. This large crustal upfold has been worn down over millions of years. First the uppermost limestones were stripped off the summits, to survive only in the surrounding plains; next, the Old Red Sandstone was eroded along the crest to reveal the old Silurian rocks at the core of the upfold. Thus, the upper parts of the Galtys are made up of Silurian slates, shales and conglomerates to form a series of fine conical peaks that climax at 919 m on Galty Mountain. The bulk of the mountains rise above 762 m. The outstanding arctic plant of the Galtys is the northern rock-cress found at 293 m on a rock buff west of Lough Curra. This and the Glenade cliffs, Co. Leitrim are its only sites in Ireland. It rarely flowers on the Galtys. The best area for the mountain species, according to Praeger, are the cliffs over Lough Muskry.3 Investigating the area before him, the intrepid Hart found the arctic-alpines roseroot, starry saxifrage and mountain sorrel.37

Mountain fauna

The fauna of Irish mountains and uplands contains very few surprises and, like the flora, is somewhat impoverished. None of the mountain ranges are high or extensive enough to provide the habitats for the true mountain species of birds such as are found in the Scottish Highlands – the ptarmigan, snow bunting and the dotterel. Even when it comes to invertebrates, especially the better investigated groups of butterflies and moths, the range of species is not one to go wild about. However, some interesting discoveries of relict arctic-alpine aquatic beetles have been made which might suggest that they survived the glacial phases of the Ice Age in some of the ice-free mountain summits. Here we will look more closely at the characteristic mammals, birds and invertebrates of mountain and upland areas.

Mammals

The largest living quadruped in Ireland is the red deer which is essentially a creature of the mountains and uplands. While there are several herds and scattered groups throughout the country, the deer in the Killarney Valley area, Co. Kerry, are probably the only ones with a claim to represent the native deer that roamed Ireland during the postglacial period. Once abundant throughout the country as a truly wild species, several herds managed to survive in the more remote areas of Erris, Co. Mayo, Connemara, Co. Galway, and in the Galty Mountains, Counties Tipperary and Limerick, until their extinction in the mid-nineteenth century (see here). Testimony of their once widespread distribution in Ireland is evidenced by the incorporation into numerous place names of the Irish word fiadh meaning ‘deer’. For example, Cluain-fhiadh, ‘the meadow of the deer’, is a parish in Co. Waterford, and Ceim-an-fhiaidh, ‘the pass of the deer’, marks the route taken by these animals when moving from valley to valley of the Lee and Ouvane areas in Co. Cork.

Two red deer hinds (F. Guinness).

The red deer living wild in the Wicklow Mountains and woods are the descendants of escapees from Lord Powerscourt’s demesne in the 1920s, although some authors date their liberation from the 1860s.38 By the mid 1930s there were approximately 50 animals living wild in the Glencree and Glenmalur areas.39 Numbers thereafter increased to about 250–300 animals during the war. Surveys in the early 1970s found only about 75 animals living in the open uplands, centred around the Mullaghcleevaun–Kippure (about 25 animals) and Glendalough–Glenmalur (about 50 animals) areas.38 A further possible 30 were living in the woodlands near Glendalough to give a total population of approximately 105 for the Wicklow hills. Numbers since then have prospered because counts in June and August 1971 found a minimum of 168 and 187 respectively in the Wicklow upland area.40

It is remarkable that there was no published systematic work on the diet of red deer in Ireland until 1993 when Sherlock & Fairley gave an account of the food of a small herd (a stag, five to seven hinds and calves) living in a 24 ha enclosure of open terrain, at Mweelin in the Connemara National Park, Co. Galway.41 The altitude ranged between 60 m to a maximum of about 120 m. The vegetation of the this area comprised 36% grassland/heath, dominated by heather and purple moor-grass; 35% peatland, dominated by purple moor-grass, common cottongrass, black bog-rush, bog asphodel and bog-myrtle; 16% grassland/bracken, dominated by bracken with the main grass being Yorkshire-fog and 13% grassland, comprised mainly of creeping bent, Yorkshire-fog, mat-grass, sheep’s fescue and sedges of the genus Carex. The food of the deer was determined by faecal analysis of 50 samples collected over one year. Grasses were the main food, forming at least 75% of the diet – primarily sheep’s fescue, creeping bent, sweet vernal-grass and Yorkshire-fog. The last three species were eaten most in summer and least in winter. Purple moor-grass, the dominant grass of the area, was only of importance in early summer when most palatable. Heather, the second most important food, was mainly eaten in winter. The diet of the Connemara red deer was comparable to that of the red deer living in the Scottish Highlands.

The goat is a frequent inhabitant of many Irish mountains. Here they are feral, having descended from domestic stock, either escaped or turned out by farmers mostly in the early part of this century. When in the wild for several generations, and sometimes within ten years, domestic goats revert to the wild or feral form. Those that have lived in the wild longest are shaggiest, wearing less patterned coats than their domesticated cousins. Despite the modern dairy goat weighing approximately twice that of the feral variety, there is no evidence to support a common assertion that feral goats represent a throw back to a wild type or ancestor of the modern goat. The degree of genetic purity of feral goats is considered high if there are no hornless adults and if none of the goats have small dangling tassels of hair on either side of their throats. Both these features are relatively recent characteristics of modern domesticated goats.