Полная версия

Collins New Naturalist Library

Many goats that were released into the wild have bred successfully to form small herds which have maintained and, in some cases, increased their numbers during the past hundred years. Feral goats are thought to live for about 12 years and weigh, on average, about 51–63 kg. They are browsers on vegetation, rather than grazers, and can cause damage to trees by stripping off the bark, especially during cold weather – ash, elm, yew, rowan, holly and hazel are favourite species to nibble. Lever remarks that approximately 20 goats living on the cliffs of Rathlin Island, Co. Antrim, are possibly the descendants of some liberated in about 1760, while those on Achill Island, Co. Mayo, also date from about the mid-eighteenth century.42 In the Mullagh More area of the Burren, Co. Clare, a lowland herd of approximately 60–70 feral together with domestic goats wander and feed off the limestone pavement and in hazel scrubland. They move around in sub-groups with considerable interchange of individuals between the different herds. They also welcome more domesticated beasts in their midst, thus demonstrating the openness of the feral gene pool to new blood. Rutting starts about mid-September, intensifies in October, and is over by the end of December. The first kids are born five months after mating. A feature of the Burren goats is the unusually high survival rate of kids. The availability and high nutritional status of the food supplied by the karst environment – despite appearing rather impoverished to the layman – probably accounts for such healthy results.43

Feral goat.

The goat in Ireland is celebrated as the central figure in the ‘Puck Fair’, a ceremony dating back to at least 1613. A male goat is first crowned as Tuck King of the Fair’ and then ‘His Majesty Puck King of Ireland’. According to Murray, quoted by Whitehead,44 the name Puck is a derivative from the Slavonic word bog, which means God.

The Irish hare, once considered to be a separate species until a critical examination demoted it to the rank of a subspecies Lepus timidus hibernicus of the mountain hare, occurs only infrequently and at very low densities on Irish mountains. When disturbed from its ‘form’ or day resting place on the hillside, it takes off madly, sometimes pausing upright on its hind legs to examine the intruder, to another distant destination on the mountain. In northwest and west Scotland these mountain hares frequent the arctic and alpine zones of the high summits, sheltering there amongst the boulders. Further south in northern England, in the Peak District mountains, the species is generally confined to the heather and cottongrass in vegetation zones that are found between 300 and 550 m above sea level. On the Isle of Man, a sort of halfway house to Ireland, they are restricted to a generally lower altitude, between 153 and 533 m. In Ireland the hares seem happiest on even lower mixed farmland habitats. Here they have little or no competition from the brown hare, normally absent from these parts. On the lowland Irish farmlands the mountain hares reach densities of up to ten times higher than recorded on lowland moorland bogs – a response to better feeding conditions and shelter.45

Birds

At the Annacoona cliffs in the Gleniff Valley, Co. Sligo, numerous ravens populate the air above the escarpments. One unusual species here, however, nearly 10 km from the sea, is the chough, rarely found breeding so far inland. The 1982 national chough survey showed that three-quarters of all inland breeding sites were found within 8 km from the sea; the site furthest out was 19 km away in Macgillycuddy’s Reeks, Co. Kerry.46 The Gleniff choughs are therefore quite remarkable. Another unusual bird around the cliffs, noted in the summer of 1996, was the mistle thrush, a species unknown in Ireland before 1800 when the first one was shot in Co. Antrim. Soon afterwards it bred for the first time in Co. Down and since then the thrush has been on the increase and has colonised almost the whole of Ireland. Not normally associated with bare and naked landscapes, the Gleniff birds were probably breeding in the wych elm or rock whitebeam trees that seem to sprout out of the cliff faces. However, mistle thrushes have also been known to nest on rocks.47

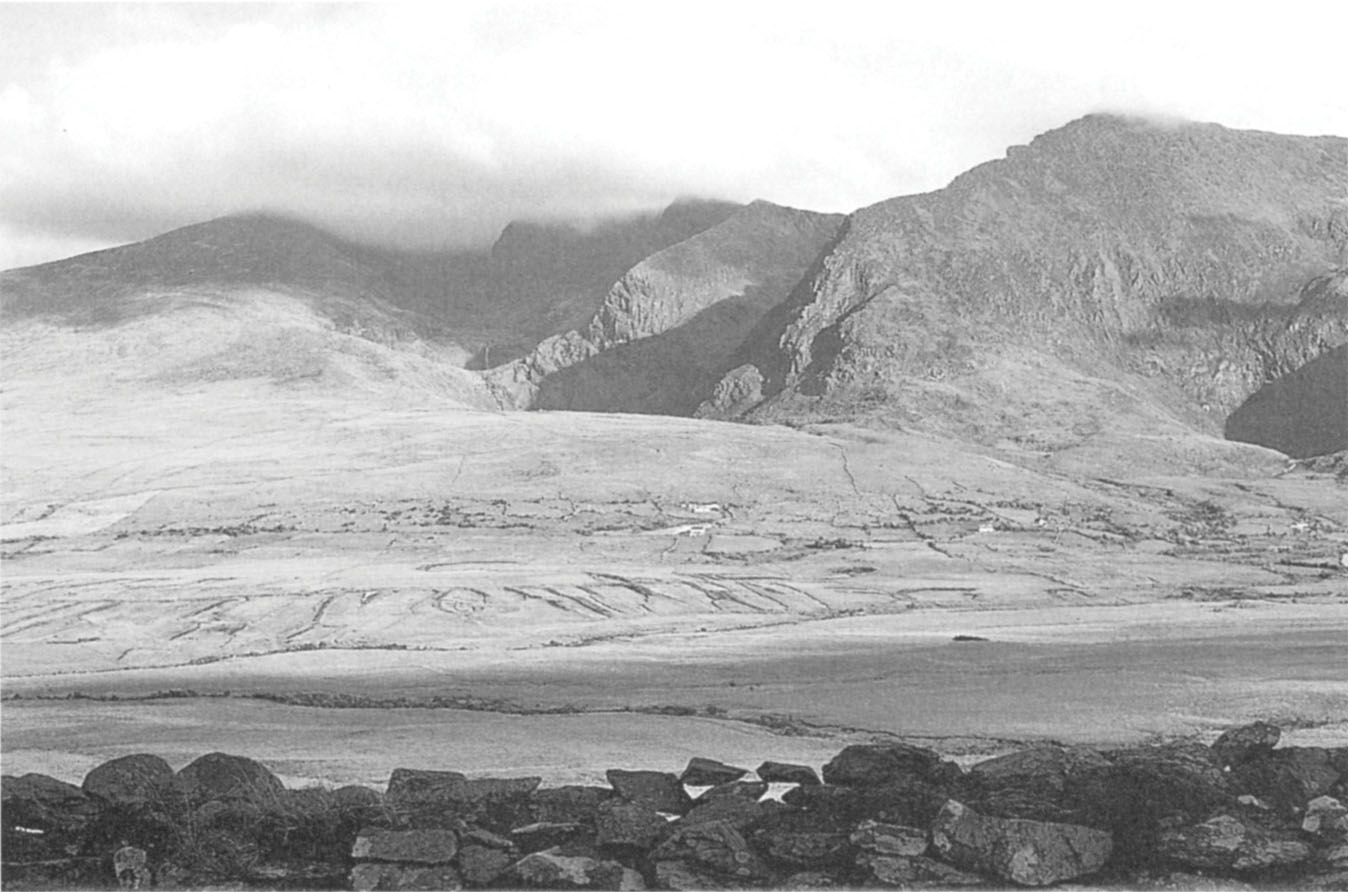

The ring ouzel, a summer visitor from northwest Africa and the Mediterranean, is the only bird confined to the higher and wilder mountain areas of Ireland. This is a somewhat mysterious thrush, not well known to Irish naturalists. Prior to 1900 it bred in all counties except Meath, Westmeath, Longford and Armagh,48 but breeding numbers have declined this century to an estimated population of only about 270 pairs, found principally in the Wicklow Mountains, the Mourne Mountains, Co. Down, the mountains of north and west Donegal, and the Kerry mountains – where they may have been increasing in recent years. They are also reputed to be in the mountains of south Connemara although Whilde writes that they have not been reported nesting there for many decades.49 The male is as black as the male blackbird but it has a white bib; the female, brown like her counterpart, has an off-white bib.

Although several historical records of breeding at sea level exist, the ring ouzel seldom nests below 300 m. Steep-sided valleys and ravines are favoured habitats with most nests placed on rock outcrops or ledges. Abandoned buildings and walls will sometimes be used, as well as dense bracken or heather. Little is known about the ecology of the ring ouzel in Ireland. Some basic studies would be most valuable.

Eight other birds could be said to be characteristic but not dependent upon mountain and upland areas. These are, in descending order from the summit: peregrine falcon, raven, hooded crow, hen harrier, meadow pipit, merlin, red grouse and the golden plover. Both the red grouse and golden plover also occur on lowland blanket bogs and they are discussed in Chapter 4.

The peregrine and raven inhabit all the major inland and coastal mountain systems where there are suitable cliffs for nesting. They are equally at home in coastal cliff habitats. Both are widespread throughout the country. The numbers of breeding peregrines in the Republic prior to 1950 was estimated rather uncertainly at some 180–200 pairs. A dramatic population decline, similar to that experienced in Britain, followed during the 1950s and 1960s. Possibly as few as 14 pairs were thought to have been successfully breeding in Ireland by 1970.50 This was due to the presence in the countryside of seeds dressed with organochlorine chemicals to prevent insect attack on crops. These were eaten by the woodpigeon, stock dove and rock dove which in turn were preyed on by peregrines which accumulated in their bodies an ever increasing load of the persistent chemicals. If not directly killed by the poison, sub-lethal levels interfered with the metabolism of calcium, affecting its deposition in egg shells. The resultant thin shells led to a high incidence of egg breakages, and elevated residue levels in the embryos brought about a decline in breeding success. Without enough young birds recruited, the population went into serious decline. It was only when the chemicals were withdrawn that the population began to recover. In 1981 all Northern Ireland and approximately 50% by area of the known breeding range in the Republic were surveyed and at least 278 breeding pairs noted.51 Today there are probably over 500 breeding pairs throughout the whole island. Numbers are still increasing with most of the old traditional breeding sites once again occupied while new sites are being established. Quarry-nesting peregrines, first noted in the late 1970s, are on the increase. A survey of 48 quarries, active and disused, in nine counties of eastern Ireland in 1991 and 1992 revealed 21 breeding pairs. If this occupancy rate was extended to all the 300 quarries in the Republic then there may be up to approximately 130 breeding pairs of peregrines in this somewhat unusual habitat.52 In 1977 some 35 pairs bred in Northern Ireland quarries.

Comeragh Mountains, Co. Waterford, where ring ouzels breed.

In 1986 Noonan carried out a study of peregrines breeding in 2,025 km2 of Co. Wicklow and found 34 territories, or one pair per 60 km2.53 The 12 successful eyries produced 2.4 fledged chicks per nest. This figure compared with 2.17 fledged chicks from a longer-term study in five southeastern counties in Ireland over the period from 1981–6. However, when these results were expressed as the mean number of chicks fledged per pair of peregrine holding a territory the figure was only 0.91 chicks. It was also found that breeding performance at coastal, compared with inland, sites was higher with 0.95 and 0.78 chicks respectively produced per pair of peregrines holding territory.54

Ravens are more numerous than peregrines in Ireland with an estimated population of 3,500 breeding pairs in 1988–91.55 However, this would appear to have been a gross over-estimate, and the true breeding population is more likely to be in the order of 1,000 pairs, divided between mountain, upland and coastal habitats.56 Their shared interests in sometimes similar habitats with peregrines can lead to spectacular aerial encounters. But how do two large and extremely agile birds get along together when they require similar breeding sites? The mechanism for apportioning out available cliffs is not clear but may well be based on precedent of who got there first. If either occupant moved off, for whatever reason, or died, the site would be up for grabs. Their mutual respect for each other has been witnessed and filmed by the author in aerial encounters during which a peregrine will playfully stoop on a raven that will suddenly flip over on its back and point its massive claws upwards, without actually grappling with the peregrine.

Historically ravens were relentlessly persecuted by man because they were perceived as predators of young lambs and sickly sheep, and by 1900 only a few pairs survived in a small number of remote coastal areas. With the relaxation of this murdering grip at the beginning of this century, a remarkable population increase commenced which has led to the species unfurling into virtually all the hills and mountain areas of the country. In a study of ravens in Co. Wicklow during 1968–72 a population density of one breeding pair per 25.3 km2 was found, close to the one pair per 23.9 km2 recorded in north Wales moorland for enclosed sheep farms. In both Wicklow and Wales the raven occupied generally similar habitats.53 Highest densities are in the western uplands where the greater sheep numbers provide the attendant supplies of carrion – the amounts of which were indicated by a study on the blanket peatlands around Glenamoy, in west Mayo, during the early 1970s. The stocking levels on these bogs at that time was roughly one ewe per ha, and losses between October and April were estimated at about 7–10% of total numbers. On average about 1.0–1.4 carcasses per km2 per month became available to the predators. It was also found that carcasses weighing 30–35 kg disappeared in less than two weeks, indicating the intensity of scavenging by ravens, hooded crows and foxes.57

The hooded crow is more a bird of the uplands but, like the peregrine and raven, it has an interest in other habitats, as evidenced by the large population in Ireland, estimated at about 290,000 pairs. The success of the species is a reflection of their ability to adapt to all available food sources. A constant feature of the mountains and uplands, hooded crows move around singly or in pairs, always on the scrounge for sheep carrion or nests of other breeding birds that are quickly plundered. In the mountains and uplands they generally build their nests in low, often isolated trees but will also resort to cliffs and low bushes. Essentially carrion feeders, they have done well in recent years, seldom short of a dead lamb or ewe whose carcasses have increased proportionately with higher stocking densities. During the winter hooded crows often come together in large roosts: close to 170 individuals were counted in one flock at Youghal, Co. Cork on St Patrick’s Day in 1978. As a subspecies of the all black crow, hooded crows will interbreed with the black carrion crow and produce fertile offspring. However, the opportunity for matrimony is not great in Ireland as the carrion crow is scarce, and found principally in the northeast of Ireland – although it has been creeping down southwards towards Dublin in recent years.

The hen harrier is most likely to be seen quartering moorland below 500 m, especially in areas covered by young forestry plantations which, in their early stages of development, offer excellent breeding habitat for the species. A dense growth of tall vegetation such as heather is also suitable nesting habitat. Formerly widespread throughout Ireland, these docile-looking birds were persecuted by gamekeepers to the point of extermination in the second half of the nineteenth century and were thought to have become extinct in 1954. Fortunately a few pairs were lurking in the Slieve Bloom Mountains, Co. Laois, and on the Waterford/Tipperary border. Numbers picked up dramatically as large areas of amenable breeding habitat became available to the species through a reinvigorated State afforestation programme. By 1973–5 there were 250–300 breeding pairs on the Irish uplands.58 Since then, however, they have declined again, dropping to probably fewer than 100 pairs. Reasons advanced for this reversal relate to maturing forestry plantations together with the clearance and reclamation of marginal uplands, representing a loss of breeding and hunting habitat for the species.59 However, this explanation is not entirely satisfactory as afforestation is not a thing of the past and new plantations, providing renewed attractive habitat, are still being created all around the country. Today most of the estimated 60–80 pairs are located in the uplands of Kerry, Limerick, Cork, Clare, Tipperary and Laois.60 Some also breed in Tyrone, Fermanagh and Antrim. Recent sightings in Galway and Mayo may relate to breeding birds. Hen harriers have also decreased in England and Wales but appear to have remained stable in Scotland. Recent estimates for the population breeding in western Europe, excluding Ireland and Britain, gave 4,160–6,610 pairs.61

Hooded crow. Widespread throughout Ireland. (F. Guinness).

The buzzard, a common breeding bird on inland cliffs and in woodlands in Donegal, Derry, Antrim and Down during the nineteenth century, was persecuted by shooting and poisoning until it became extinct shortly before the turn of the century. At the same time buzzards remained widespread in the western upland areas of Britain. Following several attempts earlier this century to reestablish themselves in Antrim they finally managed reinstatement there in the early 1960s. Since then they have spread to all six Northern counties with an estimated population of 120 pairs in 1991. The population has also spread out of the North into adjoining counties and southwards into the Republic where the population rose from one known pair in 1977–9 to 26 pairs reported 1989–91. Most were in Donegal (13 pairs) followed by Monaghan (7 pairs), Wicklow (3 pairs), Louth (2 pairs) and Cavan (1 pair).62 Their recolonisation has been facilitated by a more enlightened attitude by game keepers and farmers and a reduction in the amount of poison laid to protect lambs from corvids and foxes. Moreover the use of strychnine was banned in the Republic in 1992 in conjunction with an attempt to reintroduce the white-tailed sea eagle to the Dingle Peninsula area.

The kestrel, despite possibly being the commonest bird of prey in Ireland, occurs at lower densities than encountered in most other European countries, the reasons for which are not entirely clear.

The passerines, apart from the ring ouzel, characteristic but not dependent upon the mountains and uplands include the ubiquitous meadow pipit, whose small size and nondescript streaky brown plumage belie its tenacity for survival in a hostile environment. With an Irish breeding population estimated at over a million pairs there are plenty to spread around in all Irish habitats ranging from farmland, rough grasslands, young forestry plantations, peatlands and mountains and uplands where, above the altitudes of 500 m, it is the commonest nesting bird. Managing to find enough invertebrates, particularly flies (including mosquitoes) populating grassy and heathery slopes, the pipit, in turn, is the principal food item for the merlin as well as main host-cum-victim to wandering cuckoos. In recent years a decline in the numbers of meadow pipits breeding in southeastern and eastern Ireland has been noted – probably a consequence of the agricultural improvement of marginal lands. Today its strongholds are in the western and northwestern counties.

Merlins are equally at home in lowland blanket bogs as they are in the mountains and uplands. The estimated size of the Irish breeding population is 200–300 pairs, concentrated mainly in the uplands of Wicklow, Galway, Mayo and Donegal. They also occur in the uplands in Northern Ireland. A special survey carried out in 1985 by Haworth in the great expanse of lowland blanket bog between Errisbeg and Clifden in west Galway revealed the presence of 12 pairs, eleven of which were breeding on wooded islands in small lakes, the other in a coniferous plantation. Eight nests were successful in their breeding outcome and 32 merlins fledged.63 In the uplands of Wicklow merlins breed in coniferous plantations while in Northern Ireland they often settle in the abandoned nests of hooded crows. A study by Toal in Derry, Tyrone and Antrim found that of 22 recorded nests 19 had previously been taken over from hooded crows in trees and only two were on the ground. All nesting took place above 150 m and most sites were either in sitka spruce plantations, or on the edge of them.63

Other birds frequently occurring but not in any particular way tied to these regions are the wheatear which likes open spaces strewn with landmarks such as boulders under which they can nest or in hollows in turf banks, and wren, also able to exploit opportunities in seemingly barren areas. Another bird, not well known and whose ways, like those of the ring ouzel, are somewhat mysterious, is the twite, a small brown finch. It is found in the remote western coastal areas from Donegal to Kerry, but also in some mountain and upland regions where it nests in heather or low bushes. Some 750–1,000 pairs are estimated to breed in Ireland and the population is thought to be declining.60 Both the twite and the ring ouzel offer plenty of scope for study by naturalists.

Invertebrates

The coldness and harsh climate of the mountains and uplands have restricted the number of invertebrate species in these habitats and most attention has been paid by naturalists to the more spectacular butterflies and beetles. The only butterfly confined to the mountains and uplands is one of the hardiest of them all, the small mountain ringlet, which in Europe is seldom found below an altitude of 460 m. In Britain, when it occurs, it is usually between 200 and 900 m. Adults are a drab, sooty brown with a band of black spots fringing the margins of their outer wings, each surrounded by a lighter tawny zone. Its caterpillars are grass-green and feed on mat-grass. There are only four known specimens from Ireland, all preserved in the scientific collections of the Natural History Museum, Dublin, and the Ulster Museum, Belfast. One was from ‘a grassy hollow about half way up the Westport side of Croagh Patrick,’ Co. Mayo, June 1854; the second from the hilly slopes on the eastern shores of Lough Gill, Co. Sligo in 1895 and the third from Nephin Mountain, Co. Mayo in 1901. The fourth specimen is just labelled ‘Irish 30.6.18.’ Almost every year entomologists try in vain to rediscover this elusive prize but despite repeated searching it fails to be turned up, thus leading to the conclusion that it is probably now extinct. One difficulty in recording its presence is that it flies only in sunshine, spending the rest of its time lurking in damp mountain and upland grasses. If it still exists in Ireland it is most likely to be found in the Nephin Beg area, Co. Mayo, which is considered to offer the best habitat opportunities.64

The large heath, another upland inhabitant, has been recorded up to 365 m at the Windy Gap, Co. Kerry. Unlike the mountain ringlet it is not confined to mountain and upland areas, with many occurring on the lower blanket and raised bogs. The adults are on the wing for only a short time in the summer – from the middle of June to the end of July. The caterpillar is about 2.5 cm long, grass-green in colour, striped by dark green on its dorsal surface and white along the sides. It is thought that common cottongrass and purple moor-grass are probably important food for the caterpillars, as well as white beak-sedge when it is available. The large heath is a very variable species as regards its colouring and wing markings. There are several subspecies, with two recognised in Ireland – Coenonympha tullia scotica and C. t. polydama. The former is confined mainly to the south and western Ireland.65 The latter occurs in many parts of the country but its main stronghold appears to be in the Midlands and in the north of Ireland.66

The emperor moth, easily identified by its prominent eyespots on the upper and lower wing surfaces, is on the wing from April to end June especially on upland boglands. Another moth, the beautiful yellow underwing, takes it name from the yellow central area, bordered by black, on the underwings. Both these moths may be encountered on Irish uplands and mountains together with numerous other smaller, paler moths exploding upwards for a brief dashing flight when disturbed by a hill walker or roaming beast before plunging back down into the protective vegetation.

In contrast to the highly mobile butterflies and moths, many other invertebrates are yoked to their local environments. One interesting group is the water beetles belonging to the family Dytiscidae which, although most are well able to fly, tend to remain confined to very specific aquatic habitats, especially within the mountainous environment. These water beetles have evolved adaptive devices to make their aquatic lifestyle easier – their heads are generally sunk into the thorax and the body is smooth and rounded, both facilitating their passage through water. They also possess broad hind legs, flat and fringed with hairs to act as efficient paddles. Although rising to the surface, tail first, to renew the oxygen supply is still necessary, the water beetles can also hibernate, particularly in order to overcome cold conditions. Both the adults and larvae are aggressive carnivores. Some larvae reach up to 6 cm long and will successfully tackle small fish and even take on, working with their fierce looking hard jaws, a tasty-looking finger of a hapless bug hunter. Several members of the Dytiscidae found in Ireland have been identified as glacial relicts that ‘chilled out’ in their mountain-top pools as the ice sheets were banging around in the valleys below.

A particularly rich site for these relict species is the top of Doughruagh Mountain (526 m), a northern outlier of the Twelve Bens of Connemara, west Galway. Several small, shallow pools pepper the summit. The vegetation is meagre and includes bog pondweed, water lobelia, water-milfoil, Myriophyllum sp., bulbous rush and the sub-aquatic moss Scorpidium scorpioides. These often mist-shrouded and rain-drenched pools are the unlikely spots, because of their barren mountain summit locations, for spawning frogs. The ensuing tadpoles enter into the diet of the rapacious larvae of two very rare Dytiscidae found here: the alpine and smallest of the great diving beetles Dytiscus lapponicus and an arctic-alpine species Agabus arcticus. The nymph of another glacial relict, the water boatman Glaenocorisa propinqua, has also been recorded here67 as well as on the Peakeen Mountain, Co. Kerry and in the Blue Stack Mountains, Co. Donegal. It has also been recorded from Lough Nacartan (30–60 m above sea level), Killarney, Co. Kerry, and in Upper Lough Bray (425–457 m above sea level).68 The only other Irish records of Dytiscus lapponicus are from Co. Donegal, the Partry Mountains, west Mayo and Co. Kerry. As for Agabus arcticus, it has been found in pools in the Wicklow Mountains and from Glenariff and Lough Evish in Co. Antrim. The adults in the population of the glacial relict stonefly Capnia atra living in the Devil’s Punch Bowl (over 700 m above sea level) near the summit of Mangerton Mountain, Co. Kerry, are brachypterous – short winged and non-flying – considered to be a selective advantage as because they cannot fly they are prevented from being blown away to an unsuitable area in such a windswept region.69 Another insect survivor from the Ice Age is a small alpine caddisfly Tinodes dives,