Полная версия

Collins New Naturalist Library

The oceanic flora

The lowlier plants – ferns, mosses, liverworts and lichens – reproducing by minute, wind-blown spores, have less difficulty in crossing expanses of sea, and the mild, oceanic climate of Ireland has been particularly favourable to their colonisation. Especially in the extremely humid west, the profusion and luxuriance of these plants is a striking and important feature of the vegetation. In many of the western woods, communities of fìlmy-ferns, mosses and liverworts cover the rocky woodland floor and lower tree trunks, while lichens are most conspicuous on the upper trunks and branches. Many of these species have an extremely restricted European and even world distribution, confined to the far western seaboard and the Atlantic Isles of the Azores, Madeira and the Canaries (Macaronesia).

The most famous is the Killarney fern, much the largest and finest of our three fìlmy-ferns, once locally abundant along the rocky streams and in the lower corries of the southwestern mountains, but reduced to rarity by indiscriminate collecting. The moss-like Tunbridge and Wilson’s fìlmy-ferns are in amazing quantity in many rocky woodlands and shady block screes, while the hay-scented buckler-fern, with its distinctive crinkly fronds, grows large and in unusual quantity. Visitors from Britain are struck by the general abundance in western Ireland of the royal fern, often to be seen in great dense patches on peaty ground. The fern collectors made less impression on it here than in western Britain, where it was once also abundant in places. The Irish spleenwort is a very rare and beautiful fern of exposed dry rocks and banks in southern Ireland and is unknown in Britain, but another Mediterranean-Atlantic fern of similar habitats, the lanceolate spleenwort, is more frequent in western Britain than Ireland. The delicate maidenhair fern, a widespread species in warmer parts of the world, grows luxuriantly on limestone, especially in crevices of the Burren pavements. Also of interest are the liverworts Cephalozia hibernica, Lejeunea flava, L. hibernica and Radula holtii, found in Ireland but not in Britain (see Appendix 1).

The profusion of ferns, mosses and liverworts, including many oceanic species, extends up the mountains. In the extreme west, the shady corries and slopes facing between north and east have communities of leafy liverworts amongst or below heather or other dwarf shrubs and on rock ledges. These are virtually identical to liverwort carpets in similar situations on the equally wet mountains of the western Scottish Highlands. They contain species notable for their highly discontinuous world distribution in humid mountain regions as far apart as southwest Norway, British Columbia, Alaska, the Himalayas and Yünnan (e.g. Mastigophora woodsii, Herbertus aduncus and Pleurozia purpurea). The abundance of the woolly fringe-moss on stable block screes, bog hummocks and peat hags, and its dominance on many high mountain tops, is another feature of the oceanic climate.

Many plant introductions from warmer regions have flourished in the mild Irish climate. The luxuriant and colourful hedges of fuchsia are one of the most distinctive features of the west, while the invasion of woodland by rhododendron has created a conservation problem. The southwest, with lowest incidence of frost, has well-established growths of escallonia, New Zealand flax, giant rhubarb, the hedge veronica Hebe elliptica and the cabbage palm tree.

3

Mountains and Uplands

Nothing more sharply exemplifies relativity than a mountain. A 100 metre-high hill in a flat landscape assumes mountainous proportions, but a normal arctic-alpine plant, casting a cold eye for a frosty north-facing cliff, would pass it by. Compared with their cousins in Wales, Northern England and Scotland, Irish mountains are not only generally lower but also cover a smaller proportion of the landscape and, as a consequence, offer fewer opportunities for a rich mountain, alpine or arctic-alpine flora and fauna.

Raven & Walters1 define a mountain as land over 2,000 ft or 610 m – in practice any height above 600 m is generally accepted as mountain land – which puts only about 0.3% or some 240 km2 of Ireland in the ‘mountain’ category with approximately 190 peaks penetrating the 600 m limit. ‘Upland’ is a more difficult issue and is taken to include all land between 300 and 600 m and as such would embrace some 4,100 km2 of Ireland. Together, mountains and uplands occupy 5% of the country’s surface. Most elevations are located in the coastal counties with the notable exception of the Galty Mountains rising up from the south Tipperary lowlands to reach 919 m.

The great Irish botanist Nathaniel Colgan was the first person to point out that of the 67 species comprising the so-called Watsonian ‘highland’ group of plants found in Britain (named after the British botanist H.C.Watson), only 42 occurred in Ireland.2 However, as Praeger has said, Watson’s definition of highland plants – ‘species chiefly seen about mountains’ – does not fit well in Ireland, where many of these plants are found in more places than just the mountains. Sixteen of them occur as far down as sea level.3 In the 1950s Raven & Walters provided a much more rigorous list of 150 ‘mountain’ species recorded in Britain and Ireland.1 The vast majority of these fall into the ‘arctic-alpine’ category, i.e. plants that occur both in the Arctic and on some or all of the main European mountain ranges. If one ignores the taxonomically complicated and controversial dandelion-like hawkweeds (Hieraciums) and the real dandelions (Taraxacums), only 58 species or 39% of the Raven & Walters list are found in Ireland.

Despite the impoverished representation of the ‘highland’ and ‘mountain’ plants in Ireland, Colgan made some interesting discoveries in the Mayo and Galway Highlands. ‘It may sound like a paradox to say that the botanical survey of an Irish mountain region derives a peculiar zest from the very poverty of our flora in alpine species. Yet the assertion may be made with perfect truthfulness. That the rapture of discovery varies directly with the rarity of the object sought for, that the value of the thing attained is measured by the labour of attainment – these are time-honoured truisms in every system of proverbial philosophy; and their essential truth is daily borne in upon the mind of the botanist who devotes himself to the exploration of any of the mountain groups in Ireland.’

The natural history interest of Irish mountains and uplands derives primarily from their extreme ecological conditions and their possible role as refugia for flora and fauna during the Ice Age. Some of the present day plants and insects may be relict species, survivors of these earlier days. The astringency brought about by poor soil conditions, few nutrients, high rainfall, searing winds, low temperatures, cold and short summers, frost and intense sunlight underpins the existence of a remarkable assemblage of mountain lichens, mosses, ferns, flowering plants, invertebrates and vertebrates that are at home in and, in many cases, restricted to, the mountain environment. Plant and animal species that live in such conditions are particularly interesting ecologically because to meet the prerogatives of survival and reproduction requires a strategy of adaptive responses.

Relief of Ireland. From F.H.A. Aalen, K. Whelan & M. Stout (eds) (1997) Atlas of the Irish Rural Landscape. Cork University Press.

But what about the physical framework of Irish mountains? What about their environmental conditions – the soils and climate? And finally, what kind of mountain flora and fauna characterises Irish eminences and where are the best places to encounter it?

Physical frameworks

Most Irish mountains and uplands are formed of the older and harder rocks, the most ancient dating from the Precambrian period some 600 million years ago. These are the schists and gneisses (formed mainly of quartz, feldspar and mica, differing from granite in the size, colour and configuration of the crystals) that were originally laid down as sediments in the seas prior to severe alteration by pressure and heat. The effects of these processes were to change radically the character of the minerals and particles that made up the sedimentary rocks. Also included amongst the oldest rocks are the granites, originating in the molten material spewed out from deeper sources some 400 million years ago and injected into the surface layers. Mountains built of these earliest rocks are found mainly in Donegal, west Mayo, west Galway and in the Leinster region – especially the Wicklow uplands. The granites of the Mourne Mountains, Co. Down, were formed 350 million years later. During the Cambrian period, slates and quartzites were born out of sedimentary marine muds and sands. These rocks are found mainly in north Wicklow, Wexford and at Howth in Dublin. More recently still, in the Ordovician period, shaly rocks with some sandstones and limestones, including some molten rocks that have flowed into them, formed in the sea as sedimentary depositions. These amalgams of rocks are found mainly in the southeast of Ireland.

The Devonian grits and sandstones, often called ‘Old Red Sandstones’, and principally made up of fresh or marine water deposits, form the bulk of the Cork and Kerry highlands. Closer to us still, Carboniferous limestones, the result of deposition of millions of tiny calcareous shells and marine creatures in warm tropical seas around 300 million years ago, line the floor of the Central Plain, while in the Burren, Co. Clare, these limestones thrust up to produce grey rounded hills. In Co. Sligo the Benbulbin mountain range has been carved from great thicknesses of such limestones. As to the most recent Irish mountains, the extensive upland plateau in Co. Antrim and eastern Derry, they are the result of outpourings of lava belched up from underground sources some 65 million years ago.

The largest continuous upland area in Ireland is in Co. Wicklow where the granite hills higher than 300 m range over 520 km2 and peak at 925 m on Lugnaquillia Mountain, which, unlike most of the other parts of the Wicklow uplands, has retained its Old Red Sandstone capping. The original body of the Wicklow Hills consisted of sandstones, grits and conglomerates that were laid down in an ancient sea during the Ordovician period. About 400 million years ago a large mass of hot molten granite was extruded from the earth’s belly. This heaving mass pushed the overlaying rocks upwards and humped them into a southwesterly aligned dome. Later on the sandstones and other slatey rocks were eroded away, a few lingering as marginal flanks to the hills, exposing the granite core that now forms the greatest area of granite in Ireland or Britain.

Further south in Cork and Kerry it is the hard Old Red Sandstone rocks that have endured. Their limestone covering was stripped off after all the rock layers were thrust up by a gigantic lateral earth movement some 300 million years ago, and folded in a series of ridges, aligned west-east. The intervening valleys, however, retain some of the surviving limestone. Towards the western side of this mountain mass are the Macgillycuddy’s Reeks, Co. Kerry. These host amongst a cluster of tall conical peaks, Ireland’s highest mountain, Carrauntoohil, rising to 1,039 m, to the east of which are the famous lakes and mountains of the Killarney National Park.

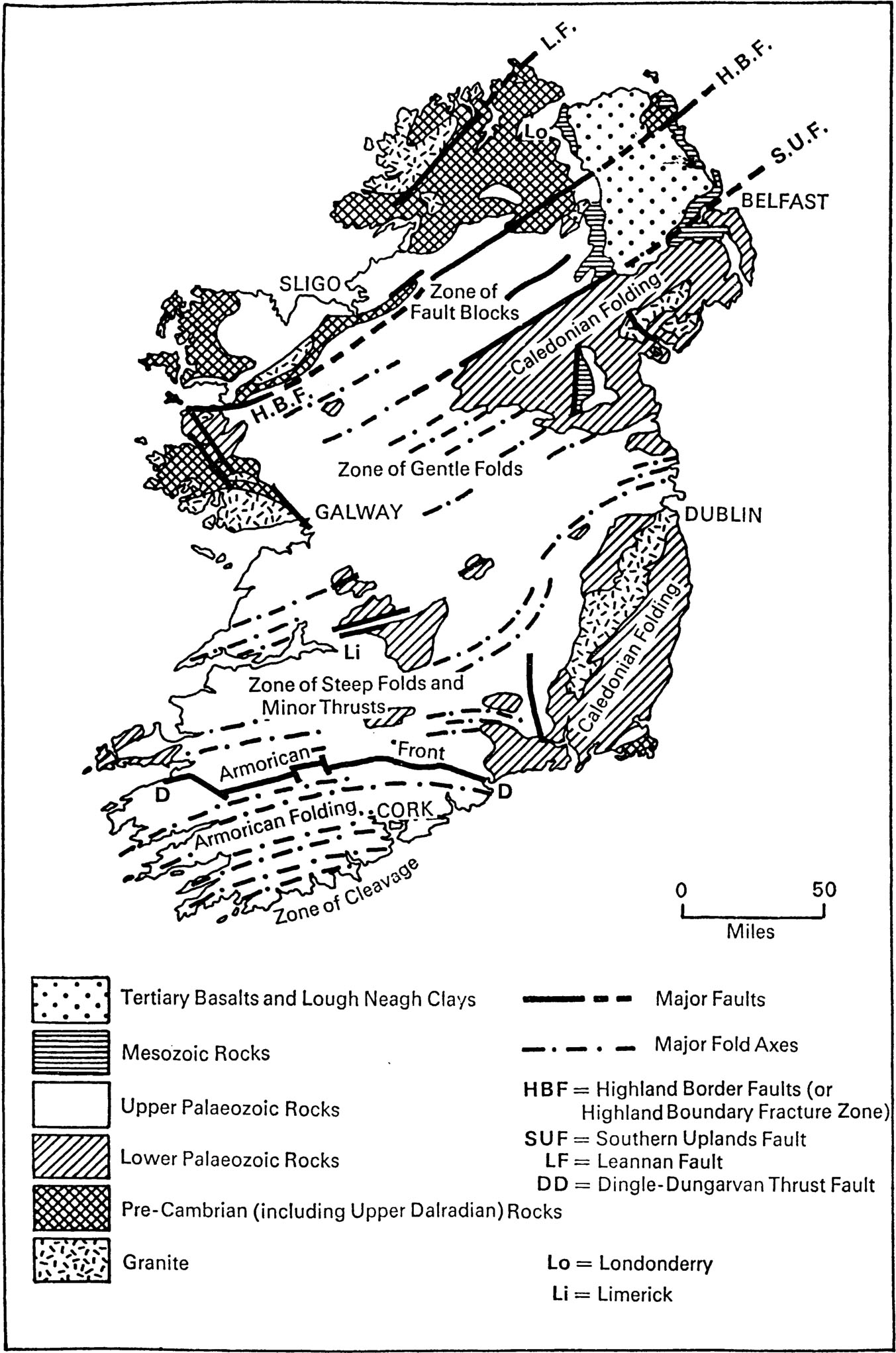

The structural geology of Ireland. From J.B. Whittow (1974) Geology and Scenery of Ireland. Penguin Books, London.

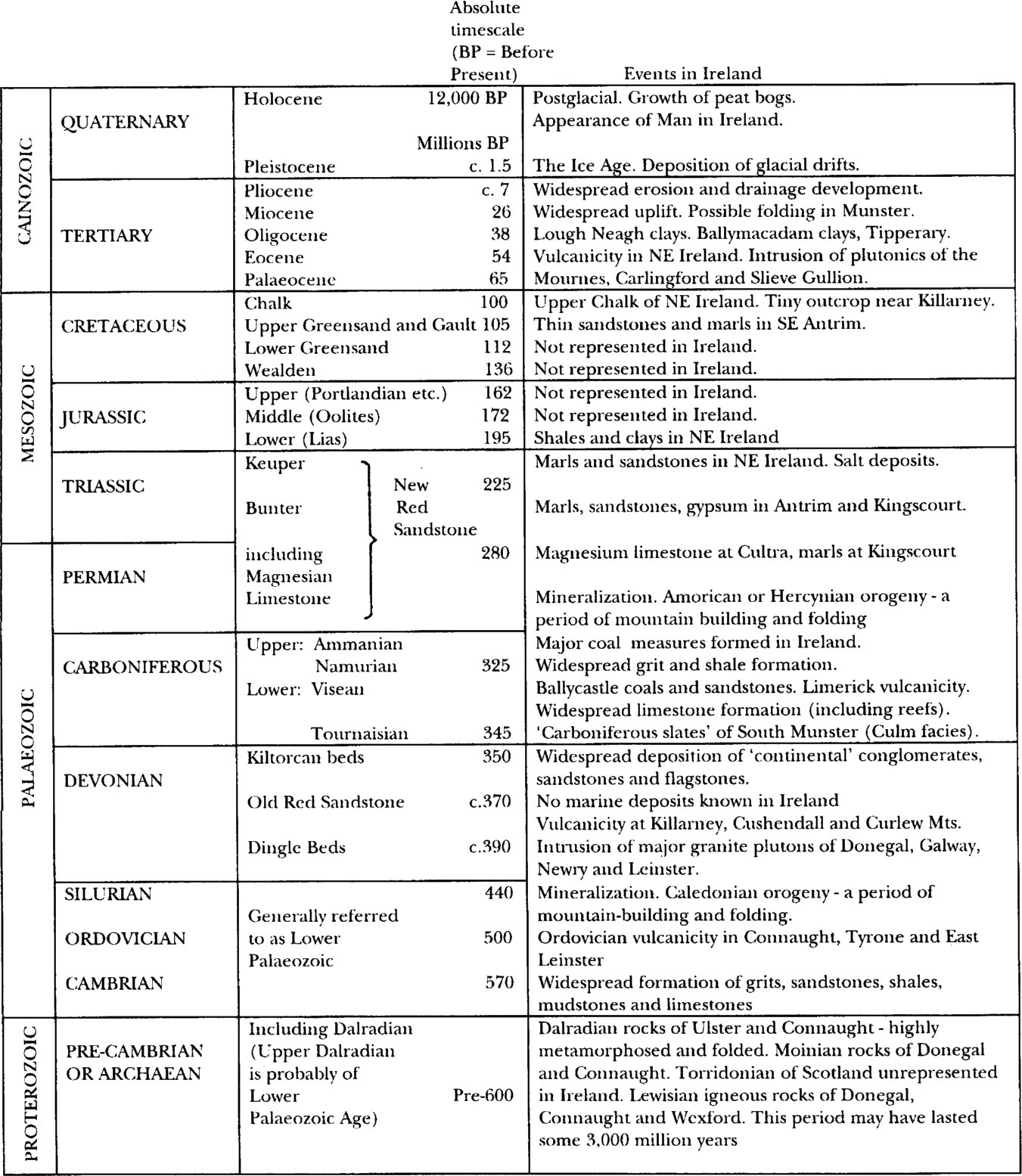

Table 3.1. Sequence of events and dates for the geological history of Ireland. From J.B. Whittow (1974) Geology and Scenery of Ireland. Penguin Books, London.

The Galway and Mayo highlands are also the result of convulsions that took place during the Caledonian mountain-building period some 400 million years ago. Hard granites in the south of Connemara and quartzites, gneiss, Silurian slates and shales in the north were pushed upwards to create hills and mountains. The Twelve Bens are made up of quartzite surrounded by Silurian schists and separated by valleys covered with blanket bog. Further north, over the Killary fjord, Co. Mayo, lies Mweelrea, the highest mountain in the west of Ireland (814 m), north of Brandon, Co. Kerry. The coastal cliffs at Slieve League, Co. Donegal, the highest sea cliffs within Ireland and Europe, plunge into the Atlantic from a height of 595 m. On the steep northeastern and landward face, one of the richest assemblages of alpine flora in Ireland looks out over blanket bogland and the cold, desolate Lough Agh below.

Rainfall, soil and environmental conditions

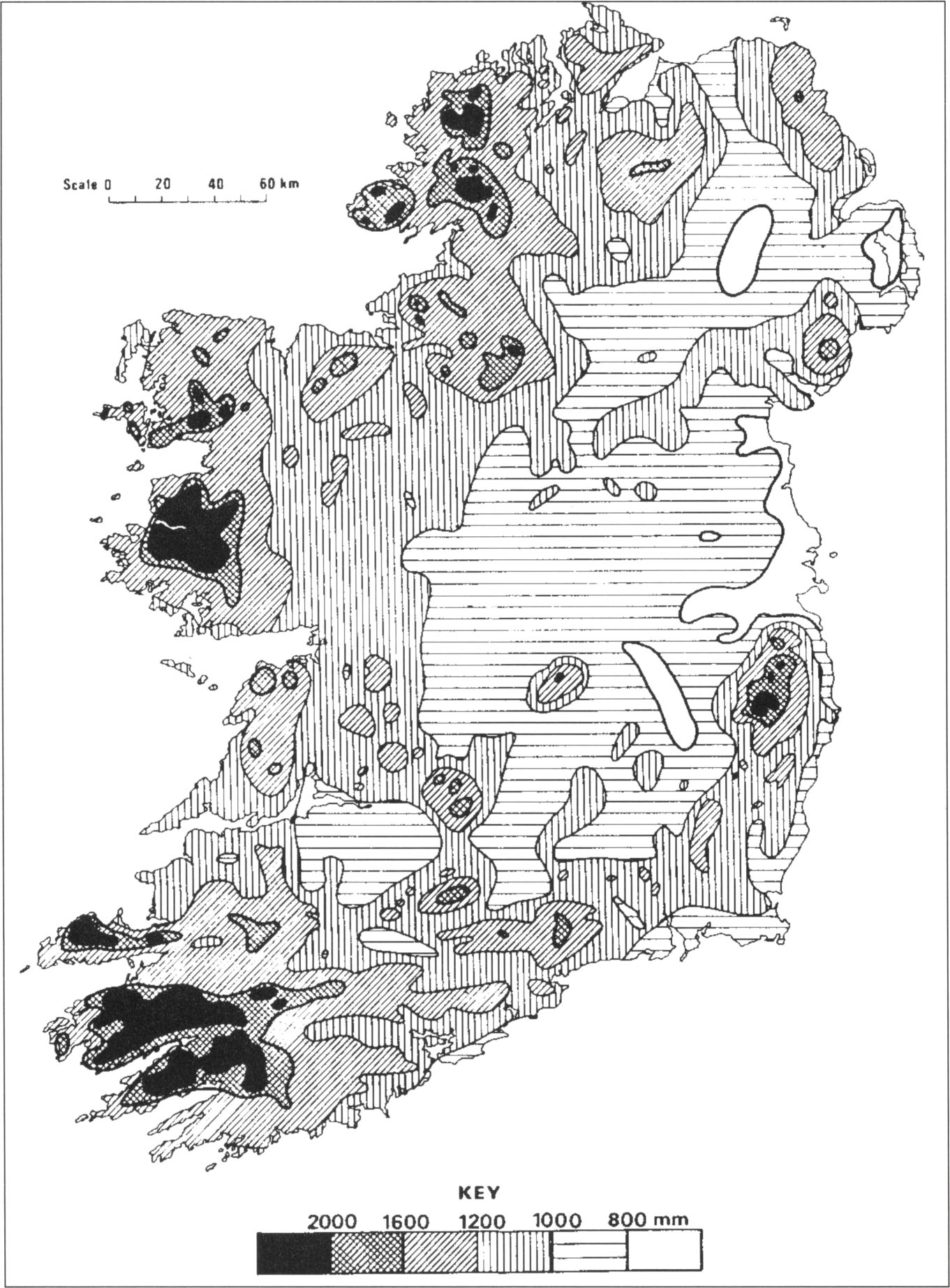

Levels of rainfall and humidity are much elevated on Irish mountains. The prevailing westerly winds are moisture-laden as they hit the west coast after travelling across several thousand kilometres of Atlantic Ocean, hence the often substantial and persistent falls of rain. Published figures from the highest recording station, set at 308 m at Ballaghbeama, Co. Kerry, show 396.5 cm of rain for the year 1960. At another station in Co. Kerry, at the Cummeragh River, 540 m above sea level, a total of 68.6 cm of rain was logged for just the month of December 1959, more than the average annual fall on the east coast. Further up the west coast at Kylemore, Co. Galway, close to sea level, the average over a 16 year period was 207.7 cm per year. At nearby Delphi, Co. Mayo, on the lee side of Mweelrea, rainfall of 254 cm per annum is not unusual, while in the wettest spots of Kerry and Galway precipitation can be as high as 250 cm per year.3 Such high rainfall encourages the development of boggy wet acidic soil and induces the leaching of nutrients. Still more important is the frequency of precipitation. The mountains of Donegal, Mayo–Galway and Kerry–Cork experience over 220 ‘wet days’ each year (a wet day is a period of 24 hours with precipitation of at least 1 mm).

Unfortunately no temperature readings are available from Irish mountains. However, for every 150 m rise in altitude the temperature decreases by approximately 1°C, so temperatures at any altitude may be estimated from isotherm maps corrected to sea level. For instance, at a height of 1,000 m the air will be at least 6.7°C colder than at sea level. The increased wind speed at the top of mountains will drop the temperature even further – a phenomenon known as the wind chill factor. Below freezing temperatures are encountered in winter as a thin white mantle covers the summits. On the country’s highest mountain, Carrauntoohil, snow can fall and lie for six months of the year, from November to early May4, while on Mweelrea there may be snow around the summit for at least 20 days each winter.

Despite some extremes, the Irish climate is essentially mild, especially in the southwest. The mean daily air temperature recorded at Valentia Observatory, Co. Kerry, 1951–80 was 10.5°C, the highest figure from eight stations throughout Ireland. The coldest months were December (mean 7.7°C), January (6.6°C), February (6.5°C) and March (7.8°C). The mean annual number of days on which ground frost was recorded at Valentia Observatory 1960–84 (grass minimum temperature less than 0.0°C) was 38.6, approximately one third the number of days recorded at eight other stations throughout Ireland.5

Wherever drainage is poor in the uplands or on the mountains, acid peat bog develops. This is one of the three main vegetation types typical of Irish high ground, the others being grassland and heath. On the exposed mountain summits, a more montane community is often present. Within the mountain environment there are many habitats hosting different groups of liverworts, mosses, ferns and flowering plants. Boulder screes, gullies, streams, vertical cliff faces, ridges and even snow fields that persist for several months each year provide specialist niches for the 58 species that are characteristic of Irish mountains and uplands.

Average annual rainfall 1951–1980. From Rohan5.

The occurrence of calcareous outcrops, pockets of base-rich rocks such as mica schists, or out-flushings of mineral rich waters from deeper below, have dramatic impacts on the mountain flora, allowing many species to flourish profusely in an otherwise acidic environment. The largest limestone outcrop and mountain range in Ireland is Benbulbin, Co. Sligo. Benbulbin ascends vertically in the upper parts to a blanket bog-covered plateau with a maximum altitude of 526 m. On first sight this smothering of peat appears to defy ecological good manners, sitting on top of limestone rock which should, according to conventional rules, be supporting a community of calcicole or lime-loving plants. Peatland communities, made up of more astringent calcifuge or lime-fleeing species are normally found in lime poor habitats. The dramatic cliff walls, hanging over the lowlands below, are where most of Benbulbin’s renowned arctic-alpine flora is to be found.

Burning and grazing are traditional agricultural practices that have moulded and shaped the upland and mountain plant communities for centuries. However, since Ireland joined the European Union in 1973 the number of sheep grazing the mountains has increased dramatically, prompted by generous subsidies and premiums from Brussels and the government. Numbers nearly trebled from 3.3 million in 1980 to 8.9 million in June 1991. The heavy grazing intensity steadily eradicates the dwarf shrubs, such as heather and other ericales, and allows their replacement by grasses and, in dry places, bracken. Under high densities of animals, peat also suffers compaction which alters its oxygenation, leading to a premature death of the vegetation skin. The mechanical trampling leads to the disappearance of peat mosses, Sphagnum spp., whose water absorbency is crucial for the ecology of the bog. Tussock-forming sedges are the most resistant to the sheep’s aggression. The compaction of peat and the loss of Sphagnum, compounded by the removal of vegetation by incessant grazing, leads to a faster runoff of water down the mountain slopes.6 During a limited ecological survey in Co. Mayo, conducted nearly eight years ago, a total of 66 selected blanket bog sites were visited with the objective of identifying the more intact areas for conservation. Twenty-five, or 38%, of the sites, covering some 12,500 ha, contained significant areas that were overgrazed. Several sites among the 25 were completely destroyed. Indeed, it is estimated that in the case of very eroded blanket bog, rock-bare in places, it would take between 5,000 and 10,000 years for just 2.5 cm of soil to be regenerated.6

How the precious alpine and arctic flora has fared under this new regime of unabated encroachment is not known. It is easier to assess the declining populations of moorland breeding birds such as the red grouse, merlin, hen harrier, and even of the Irish hare. Other impacts on upland and mountain flora come from burning, reclamation of moorland through drainage, afforestation and the application of a wide range of chemical fertilisers, often by air.

Erriff Valley, Co. Mayo. Excessive grazing by sheep (A. Walsh).

The arctic-alpine flora

David Webb, doyen of modern Irish botanists, in a critical review of the flora of Ireland in its European context, concluded that there were 16 genuine arctic-alpines in the Irish flora.7 His criteria were that the plant ‘must be fairly widespread in the arctic and sub-arctic regions of Europe and must reappear at high altitudes (at least up to 2,000 m) in the Alps (often also in the Pyrenees). But it must be scarce or absent in the intervening areas for otherwise it becomes merged in the main mass of northern continental species.’ He excluded any species that was found at low altitudes south of about 54°–55°N and any occurring in Central Europe at altitudes below 800 m in the immediate neighbourhood of high mountains. Using these criteria he excluded the following species often described by many different authorities as arctic-alpines: alpine saxifrage, marsh saxifrage, northern rock-cress, stiff sedge, spring sandwort, bearberry, cowberry and spring gentian. While all the these species are arctic they do not fulfil Webb’s other arctic-alpine criteria. According to Webb the spring gentian is a well-known example of incorrect geographic placement. It is often assumed – because of its association with mountain avens in the Burren, Co. Clare, and in the high Alps – to have an identical geographic distribution to mountain avens which is a true arctic-alpine. However, the spring gentian is common in central and southern Germany below 800 m and also present in the karst country of Slovenia. Moreover, its representation in the Arctic is extremely meagre, being confined to a few locations in arctic Russia.

The arctic-alpine species occurring in Ireland, according to Webb’s criteria, are alpine lady’s-mantie, fringed sandwort, hoary whitlowgrass, mountain avens, chickweed willowherb, mountain sorrel, alpine meadow-grass, alpine bistort, roseroot, dwarf willow, alpine saw-wort, yellow saxifrage, purple saxifrage, starry saxifrage, moss campion and alpine meadow-rue. Webb also identified the following seven ‘alpine’ and ‘arctic-sub-arctic’ species, some with reservations: alpine: recurved sandwort; alpine (with reservations): large-flowered butterwort and Irish eyebright; arctic-sub-arctic. Scots lovage and oysterplant; arctic-sub-arctic (marginal): water sedge and alpine saxifrage.

The cloudberry, which has one station in Ireland on the Tyrone side of the Tyrone/Derry county boundary in the Sperrin Mountains, is usually thought to deserve in other texts the appellation ‘arctic-sub-arctic’ but, according to Webb, it is too widespread south of the Baltic, in north Germany and Poland, to qualify for that status. Therefore it is not included in any of the above categories. All the seven ‘marginal’ species listed above are presumed to be arctic in origin, and to have spread southwards in front of the glaciers without going far enough to get up high in the Alps, Pyrenees or Carpathians.

In his seminal paper ‘On the range of flowering plants and ferns on the mountains of Ireland’ the great Irish botanist Henry Chichester Hart considered that 13 species qualified as ‘alpines’ but without giving precise criteria. Hart was perhaps the most intrepid and adventurous of all explorers of Irish mountains with an unrivalled knowledge of Irish mountain flora. His list of alpines is important as a tool for comparing the floras of various mountains throughout Ireland: cloudberry, northern bedstraw, the hawkweed Hieracium anglicum, bearberry, cowberry, juniper, stiff sedge, blue moor-grass, parsley fern, holly fern, green spleenwort, lesser clubmoss and quillwort. None meet the Webb criteria of arctic-alpines.8

Alpine and arctic-alpine species are both rare and thinly spread throughout the country. Concentrations occur principally in the coastal counties, where most mountain ranges are found, with more species in the northern than in the southern parts of the island. The elevation at which they occur increases from the north to south as temperatures are higher in the south and thus more elevation is required to find a suitable cold spot. Of 17 species analysed by Praeger that were common to the Donegal–Derry and Kerry–Cork mountains, the mean lower limit in the north was 168 m while in the south it was approximately double that, illustrating one of the few impacts of latitude on the Irish flora. A similar comparison for 12 species found in western and eastern Ireland, showed that the mean lower limit was 326 m in Down–Wicklow compared with 219 m for Mayo–Galway, a reaction thought to be due to the wet and windy conditions along the western seaboard which effectively lower the temperatures.3