Полная версия

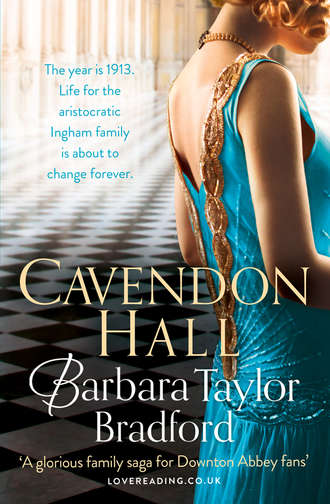

Cavendon Hall

‘I’ll go and tell Cook, and then I must get back upstairs. I’ve a lot of jobs to do for Lord Mowbray today,’ Walter explained.

‘I’ll see you later, Walter. I’m looking forward to having lunch with Alice and your girl. Everyone loves Cecily.’

Walter grinned and hurried towards the kitchen, where he hovered in the entrance, obviously explaining matters to Mrs Jackson.

Once he was back in his office, Hanson placed the two bottles on the small table near the window, and went again to his desk. He dropped the bunch of keys into the bottom drawer, glancing at the clock as he sat down in the chair. It was ten minutes to twelve, and he had a moment or two before he needed to go upstairs to check on things. He looked down at the list he had made earlier, noting that the most pressing item on it was the silver vault. He must check it, tomorrow at the latest. The footmen had their work cut out for them – a lot of important silver had to be cleaned for the parties coming up in the summer.

Leaning back in his chair, his thoughts settled on Walter. How smart he always looked in his tailored black jacket and pinstriped grey trousers. He smiled inwardly, thinking of the two footmen, Malcolm and Gordon, who had such high opinions of their looks. Vain they were.

But those two couldn’t hold a candle to Walter Swann. At thirty-five he was in his prime – good looking, intelligent and hard working. And also the most trustworthy man Henry Hanson knew. Walter brought a smile to work, not his troubles, and he was well mannered and thoughtful, had a nice disposition. Few can beat him, Hanson decided, and fell down into his memories.

He had known Walter Swann since he was a boy … ten years old. And he had watched him grow into the man he was today. Hanson had only seen him upset when something truly sorrowful had happened: when his father, then his uncle Geoffrey, and then the 5th Earl had died. And on King Edward VII’s passing. That had affected Walter very much: he was a true patriot; loved his King and Country.

The day of the King’s funeral came rushing back to Henry Hanson. It might have been yesterday, so clear was it in his mind. He and Walter had accompanied the family to London in May of 1910, to open up the Mayfair house for the summer season.

The sudden death of the King had shocked everyone; when Hanson had asked the Earl if he and Walter could have the morning off to go out into the streets to watch the funeral procession leaving Westminster Hall, the Earl had been kind, had accommodated them.

Three years ago now, 20 May: that had been the day of the King’s funeral after his lying-in-state. Hanson and Walter had never seen so many people jammed together in the streets of London: hundreds of thousands of sorrowing, silent people, the everyday people of England, mourning their ‘Bertie’, the playboy Prince who had turned out to be a good King and father of the nation. There had been more mourners for him than for his mother, Queen Victoria.

Hanson knew he would never forget the sight of the cortège and he believed Walter felt the same – the gun carriage rumbling along, the King’s charger, boots and stirrups reversed, and a Scottish Highlander in a swinging kilt, leading the King’s wire-haired terrier behind his master’s coffin. He and Walter had both choked up at the sight of that little dog in the procession, heading for Paddington Station and the train to Windsor, where the King would be buried. Later they had found out that the King’s little white dog was called Caesar. They had wept for their King that day, and shared their grief and become even closer friends.

There was a knock on the door, and Hanson instantly roused himself. ‘Come in,’ he called and rose, moved across the room. He touched the bottle of white wine. It was still very cold from being in the wine cellar. He must take it upstairs to the pantry in readiness for lunch.

Mrs Thwaites was standing in the doorway, and he beckoned her to enter when she looked at him questioningly. As she closed the door and walked towards him he saw that her expression was serious.

She paused for a moment as she reached his desk and then said, ‘Instinct told me there was something about Peggy that was off, and now I know what it is that bothers me. She’s the type of young woman who’s bold, encourages men … you know what I mean.’

Hanson was startled by this statement and frowned, staring at her. ‘Whatever makes you say that?’

‘I saw her just now. Or rather them. Peggy Swift and Gordon Lane. They were sort of … wedged together in your little pantry near the dining room. She was canoodling with him. I was coming through the back hall upstairs and I made a noise so they knew someone was approaching. Then I went the other way. They didn’t see me. Instinctively, I feel that Peggy Swift spells trouble, Mr Hanson.’

Hanson didn’t speak for a moment, and then he said, ‘There’s always a bit of that going on, Mrs Thwaites. Flirting. They’re young.’

‘I know, and you’re right. But this seemed a little bit more than just flirting. Also, they were upstairs, where the Earl and Countess and the young ladies could easily have seen them.’ Mrs Thwaites shook her head, continuing to look concerned. ‘I just thought you ought to know.’

‘You did the right thing. And we can’t have any carrying-on of that sort in this house. It cannot be touched by gossip or scandal. Let us keep this to ourselves. Better in the long run, avoids needless talk that could be damaging to the family.’

‘I won’t say a word, Mr Hanson. You can trust me on that.’

SEVEN

Daphne sat at the dressing table, staring at her reflection in the antique Georgian mirror. And she saw herself quite differently. For the first time in her life she decided she was beautiful, as her father was always proclaiming.

Unexpectedly, she now had a different image of herself, and it was all due to the two evening gowns she had just tried on.

She had been taken aback by the way she looked in the blue-and-green beaded dress, that slender column glittering with sea colours, and also in the white ball gown. Even though this was stained with ink, it had, nonetheless, made her feel happy, buoyant, full of life, whilst the long, narrow dress of shimmering beads had given her a feeling of elegance and sophistication she had never known before.

Leaning forward, she studied her face with new interest, and saw a different girl. A girl a duke’s son might find as lovely as her father did.

She thought he might have someone picked out for her, even though he had never actually said so. But he was determined to arrange a brilliant match for her, and she was certain he would do so. Her father was clever, and he knew everyone that mattered in society. After all, he was one of the premier earls of England.

A little spurt of excitement and anticipation brought a pink flush to her cheeks, and her blue eyes sparkled with joy. The idea of one day being a duchess thrilled her. She could hardly wait.

Next year, when she was eighteen, she would come out, be presented at court in the presence of King George and Queen Mary, along with other debutantes. Her parents would give a coming out ball for her, and there would be balls given for other debutantes by their parents, and she would go to them all. And after the season was over, there was no reason why she couldn’t become engaged to whichever duke’s son her father had selected.

A little sigh escaped, and she sat with her right elbow on the dressing table, her hand propping up her head. A faraway look spread itself across her soft, innocent face as she let herself float along with her romantic imaginings. Her mind was filled with marvellous dreams of falling in love, having a sweetheart, a true love of her own. A brilliant marriage. A home of her own. And children one day.

A sudden loud thumping on the door brought her out of her reverie, and she swung around on the stool as the door burst open.

A small but determined little girl with a flushed red face came storming in, heading straight for her. It was quite apparent the child was angry, and having a tantrum.

‘Whatever’s the matter?’ Daphne asked, going to her five-year-old sister, Dulcie, who was usually all sweetness and smiles.

‘I don’t like this frock! Nanny says I have to wear it. I won’t! I won’t! It’s not for a special occasion!’ she shouted, and stood there glaring at Daphne, her hands on her hips, looking indignant.

Daphne swallowed the laughter bubbling in her throat, and endeavoured to keep a straight face. In stark contrast to her own lack of interest in her clothes, her baby sister had been concerned with hers from the moment she could express an opinion. Diedre, their eldest sister, called Dulcie ‘a little madam’, and in the most disparaging tone, and avoided her as far as she could.

‘And what is the special occasion?’ Daphne asked in a loving voice, crouching down so that her face was level with her sister’s.

‘I’m having lunch with Papa,’ Dulcie announced in an important tone. ‘In the dining room.’

‘Oh isn’t that lovely, darling. I am too, and so is DeLacy.’

Dulcie gaped at her, a frown knotting her blonde brows. ‘Nanny said I was having lunch with Papa. She didn’t say you were, and DeLacy.’

‘Well, we will be there. But I do have to agree with you about the dress,’ Daphne now said quickly, wanting to placate the angry child. ‘It simply isn’t appropriate, not for lunch with Papa. You’re absolutely right. Let’s go and find something more suitable, shall we?’

Instantly the stormy expression fled, and a bright smile flooded Dulcie’s face. ‘I knew I was right,’ she exclaimed, and took hold of Daphne’s hand, her normal happy demeanour in place.

Together the two sisters went down the corridor to the stairs leading up to the nursery floor. At one moment, Daphne leaned down, and said softly, ‘You must be grown up about this. Just tell Nanny you do like this dress, but that it’s not quite nice enough for the special lunch. And you can say I agree with you.’

‘I will.’

‘You must say it sweetly; you mustn’t be rude, or angry,’ Daphne cautioned, as they mounted the stairs together.

‘I’m not angry, not now,’ Dulcie said, looking up at her adored Daphne, her favourite sister. She liked DeLacy, and they were good friends, but she was wary of Diedre. Her eldest sister constantly looked and sounded annoyed with her, and this puzzled and worried the child.

Nanny was waiting in the doorway of the nursery, and exclaimed, ‘I was just coming to look for you, Dulcie!’

Dulcie was silent.

Daphne said swiftly, not wanting the nanny to scold: ‘I think we’ve solved the problem.’ She smiled warmly, then gave the nanny a knowing look, and added, ‘It’s not often Dulcie has lunch with Papa, and it’s, well, rather a special occasion for her. And I do think she could wear a more appropriate dress. Something perhaps a little smarter. I’m sure you agree?’

‘Of course, Lady Daphne, whatever you think is best.’ The nanny opened the door wider, and they all went into the nursery sitting room.

Dulcie explained, in an earnest tone, her expression solemn, ‘I do like this frock, Nanny, but I really want to wear the blue one with the white collar. Can I?’

‘Of course, you can, Dulcie. Let’s go and look at it, and won’t you join us, Lady Daphne?’

‘I certainly will.’

Dulcie was already halfway across the floor, making for her bedroom. ‘Come on, Daphne, come and look at my best frock. Mrs Alice made it for me.’

As she followed the little girl, Daphne smiled to herself. She had long ago learned that the best way to handle her rather stubborn and independent youngest sister was to immediately agree with her, and then negotiate.

‘Oh there you are, Hanson,’ Lord Mowbray said, walking into the dining room. ‘I was just about to ring for you. Dulcie is joining us for lunch today, a special treat for the child. So would you please add another place setting?’

Hanson inclined his head. ‘Of course, my lord.’ He excused himself and hurried into the adjoining pantry.

The Earl swung on his heels and returned to the library, where he sat down at his desk and perused the list of guests he and Felicity were planning to invite to the annual summer ball in July. He added a few more names, and then sat back, pondering, wondering who had been left out, who they might have forgotten.

It was at this moment that he saw a pair of bright blue eyes staring at him. They were just visible above the edge of the huge partners’ desk. Then a moment later the whole face appeared, and he knew Dulcie was standing on her tiptoes.

She said, ‘I am here, Papa.’

‘So I see,’ he responded, laughing. ‘So come along, Dulcie, let me have a look at you.’

She did as he asked and he swung around in his chair and held out his hands to her. ‘You look very lovely this morning.’

‘Thank you, Papa. Mrs Alice made this frock for me. It’s new. It’s my favourite.’

‘I can see why,’ Charles answered, pulling her to him, bringing her closer. She truly was the most lovely child, with her almost violet eyes, and mass of blonde curls. Her pretty little face was still plump with baby fat, and she reminded him of a Botticelli angel. But one with a will of iron, he reminded himself. None of his other daughters was as stubborn.

Dulcie leaned against his knee, and looked up into his face. ‘Can I have a horse?’

Her request startled him. ‘Why a horse? Isn’t a horse a bit large for you, darling?’

‘No, I’m growing up fast, Nanny says.’

‘I agree, but you’re still not quite ready.’

‘But I can ride, Papa.’

‘I know, and you’ve enjoyed your little Shetland pony. I have an idea. I shall buy you a new pony. A better pony. Just until you can handle a horse better, when you’re a bit older.’

Dulcie flushed with happiness at this suggestion and nodded. ‘Thank you, Papa! What shall I call my new pony?’

‘I’m sure you will think of the right name. In the meantime, we must join your sisters for lunch – and, by the way, let’s keep the new pony a secret, shall we?’

‘Oh yes. It’s our secret, Papa.’

She clung to his hand as they went out of the library together. I do spoil her, Charles thought. But I just can’t help it. She’s the most adorable child. As they crossed the vast hall together, hand in hand, Daphne and DeLacy were hurrying down the grand staircase.

Both girls ran to greet him, and then DeLacy bent down, kissed her little sister on the cheek. ‘I like your dress, Dulcie,’ she murmured, smoothing a loving hand over the child’s golden curls.

Dulcie smiled back and opened her mouth to speak, and then immediately closed it. The news about the new pony was a secret, her papa had said, and she must keep it.

EIGHT

After the special lunch, as Dulcie called it, the five-year-old was taken back to the nursery by DeLacy. Their father went off to the library to finish his correspondence, and Daphne, with nothing to do, decided to walk over to Havers Lodge.

The Tudor manor house was on the other side of the bluebell woods, and was the home of the Torbett family, old friends of the Inghams. Daphne and her sisters had grown up with the three Torbett sons, Richard, Alexander, and Julian. It was nineteen-year-old Julian who was Daphne’s favourite; they had been childhood friends, and were still close.

Crossing the small stone bridge over the stream, she glanced up at the sky. It was a lovely cerulean blue, and cloudless, filled with glittering sunlight. This pleased her. The weather in Yorkshire was unpredictable, and it could so easily rain. Fortunately, the dark clouds that usually heralded heavy downpours were absent.

There was a breeze, a nip in the air, despite the brightness of the sunshine, and she was glad she had put on a hat, as well as a jacket over her grey wool skirt and matching silk blouse. She snuggled down into the jacket, slipped her hands in her pockets, walking at a steady pace.

Julian wasn’t expecting her this afternoon, but he would be at the manor house. He always practised dressage on Saturdays. He was a fine equestrian, loved horses, and aimed to join a cavalry regiment in the British Army. In fact, his heart had been set on it since he was a young boy. He would be going to Sandhurst at the end of the summer, and he was thrilled he had been accepted by this famous military academy. He had once told her that he aimed to be a general, and she had no doubt he would be in years to come.

Daphne wanted to tell Julian that her father had given her permission, over lunch today, to invite Madge Courtney to the summer ball at Cavendon. The Torbetts always came, and were naturally invited again this year. Her father had now thought it only proper and correct to include Madge. She and Julian were unofficially engaged, and when he graduated from Sandhurst, several years from now, they would be married.

Off in the distance in the long meadow, Daphne saw the gypsy girl, Genevra. She was waving; Daphne waved back, then veered to the left, walking into the bluebell woods, which she loved.

They were filled with old oaks and sycamores and many other species, magnificent tall trees reaching to the sky. There were stretches of bright green grass and mossy mounds beneath them and bushes that were bright with berries in the winter, others which flowered only in the spring.

A stream trickled through one side of the woods. Rushes and weeds grew there, and when she was a child she had parted them, peered into the clear parts of the water, seen tadpoles and tiddlers swimming. And sometimes frogs had jumped out and surprised her and her sisters.

Occasionally Daphne had seen a heron standing in the stream, a tall and elegant bird that seemed oddly out of place. She looked for it now, but it was not there. Scatterings of flowers could be found around the stream, and in amongst the roots and foliage. And of course there were the bluebells, great swathes now starting to bloom under the trees; they made her catch her breath in delight.

All kinds of small animals made their homes in the woods – down holes, in tree trunks, under bushes. Little furry creatures such as voles and dormice, the common field mouse and squirrels … She had never been afraid of them, loved them all. But most precious to her were the birds, especially the goldfinch. She had learned a lot about nature from Great-Aunt Gwendolyn, who had grown up at Cavendon, and it was she who had told her that a flock of goldfinch was called a ‘charm’. The little birds made tinkling calls that were bell-like and pretty. Her great-aunt told her they actually sang in harmony, and she believed her.

Once, her mother had called the tops of the tall trees a ‘shady canopy’ where their branches interlocked, and she had used that phrase ever since. Bits of blue sky were visible today, and long shafts of sunlight filtered through that lovely leafy canopy above her.

Their land was beautiful and she knew how lucky they were to live on it. Just to the left of these woods were the moors that stretched endlessly along the rim of the horizon. Implacable and daunting in winter, they were lovely in the late summer when the heather bloomed, a sea of purple stretching almost to the coast.

But as a family they had usually spent most of their time in the woods, where they had picnics in the summer. ‘Because of the shade, you know,’ Great-Aunt Gwendolyn would explain to their guests. She was a genuine stoic, the way she cheerfully trudged along with them, determined never to miss the woodland feasts or any of their other activities. And the ball was her favourite event – one she would not miss for the world, she would say, explaining she had never failed to attend since being a young woman. ‘I was always the belle of the ball, you know,’ she would add.

Daphne’s thoughts settled on the summer ball. For a split second, she thought of the ink stains, and the image of herself in the gown was spoiled. Then, almost in an instant, it was gone, obliterated. She was absolutely confident Cecily would make the gown as good as new, and she would wear it after all.

Over lunch, DeLacy had told their father about the terrible accident with the ink, which had been her fault. He had been understanding, and he had not chastised DeLacy. Although he had said she should have known better than to play around with a valuable gown.

The one thing he had focused on was the way Cecily had behaved, how she had been willing to take the blame to protect DeLacy. ‘She is a true Swann, instantly ready to stand in front of an Ingham. Remember our motto, DeLacy, Loyalty binds me. It is their motto as well. The Inghams and the Swanns are linked forever.’

It is true, Daphne thought. It always has been thus and it always will be. And then she stared ahead as the trees thinned, and she found herself crossing the road and walking onto Torbett land.

Daphne approached Havers Lodge from the back of the house, and she couldn’t help thinking how glorious it looked today. Its pale, pinkish bricks were warm and welcoming in the sunlight. The Elizabethan architecture was splendid, and there were many windows and little turrets, as there always were in traditional Tudor houses. And some privet hedges were cut in topiary designs.

The long stretch of manicured lawn was intersected by a path of huge limestone paving stones, which led up to the terrace. Once she reached this, she turned the corner on the right, and walked towards the front door. It was made of heavy oak, banded in iron.

She had only dropped the iron knocker once when the door opened. Williams, the Torbetts’ butler, was standing there, and he smiled when he saw her.

‘Lady Daphne! Good afternoon. Will you come in, please, m’lady.’

She inclined her head. ‘Thank you. Good afternoon, Williams.’

After he had closed the door, he said, ‘Shall I tell Mrs Torbett you are here? Forgive me, but is she expecting you, my lady?’

‘No, she’s not, Williams. I stopped by to see Mr Julian. If you would be so kind as to let him know I’m here.’

‘Oh dear! He’s gone out, Lady Daphne. He didn’t say how long he’d be. But he didn’t go riding. I saw him walking.’

Daphne gave the butler a warm smile. ‘Just tell him I was here, Williams. And please ask him to come over to Cavendon in the next few days. It’s nothing important, just an invitation I want to extend.’

‘I will, m’lady.’ The butler walked her to the door, and saw her out, and he couldn’t help thinking she was the most beautiful woman he had ever seen. Going to marry a duke’s son, she was. At least, that was what he had heard.

NINE

Daphne had been walking along the woodland path for only a few minutes when she heard a strange rustling sound. Looking around, she saw nothing unusual, so simply shrugged and went on at her usual pace. Squirrels playing, she thought, and then came to a sudden stop when she saw the heron at the edge of the stream, standing high on its tall legs in the shallow water. It was such an elegant bird.

A smile of delight flitted across her face. This was such an odd place for it to visit. She couldn’t help wondering why it kept coming back, but then perhaps it liked the stream and the woodland setting. Maybe it feels at home—

This thought was cut off when something hard struck her back, just between her shoulder blades. She pitched forward, hitting her head against a log as she fell to the ground. She lay still for a moment, stunned and overcome by dizziness. Realizing she had been attacked by someone, she endeavoured to stand up; she managed to get onto her knees, was about to scramble to her feet, but instead she was pinned to the ground from behind, and with brute force.

She struggled to free herself but the weight on top of her was too much; suddenly she was turned over, roughly, and laid on her back.

Daphne stared up at her attacker, the man who was pinning her down with such strength. He had wrapped a dark-grey scarf around his head and face, and all she could see were his eyes. They were hard, cruel, and because of the scarf she had no idea who he was. And she was terrified.