Полная версия

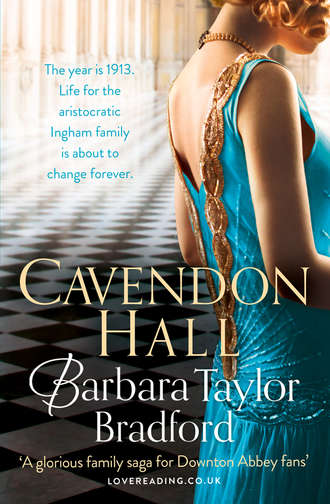

Cavendon Hall

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

Copyright © Barbara Taylor Bradford 2014

Cover photographs © Ilena Simeonova/Trevillion Images (woman); Shutterstock.com (interior)

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014

Barbara Taylor Bradford asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007503209

Ebook Edition © November 2014 ISBN: 9780007503193

Version: 2017-10-25

Dedication

For Bob, with all my love always

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Characters

Part One: The Beautiful Girls of Cavendon May 1913

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Part Two: The Last Summer July–September 1913

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Part Three: Frost on Glass January 1914–January 1915

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter Forty-Nine

Chapter Fifty

Part Four: River of Blood May 1916–November 1918

Chapter Fifty-One

Chapter Fifty-Two

Chapter Fifty-Three

Chapter Fifty-Four

Chapter Fifty-Five

Chapter Fifty-Six

Part Five: A Matter of Choice September 1920

Chapter Fifty-Seven

Chapter Fifty-Eight

Chapter Fifty-Nine

Acknowledgements

Author’s Note

About the Author

Also by Barbara Taylor Bradford

About the Publisher

CHARACTERS

ABOVE THE STAIRS

THE INGHAMS IN 1913

Charles Ingham, 6th Earl of Mowbray, aged 44. Owner and custodian of Cavendon Hall. Referred to as Lord Mowbray.

Felicity Ingham, his wife, the Countess of Mowbray, aged 43. An heiress in her own right through her late father, an industrialist. Addressed as Lady Mowbray.

THEIR CHILDREN

Guy Ingham, the heir to the earldom, aged 22. Attending Oxford University. He has the title of the Honourable Guy Ingham.

Miles Ingham, the second son, aged 14, attending Eton College. He is known as the Honourable Miles Ingham.

Lady Diedre Ingham, eldest daughter, aged 20, living at home.

Lady Daphne Ingham, second daughter, aged 17, living at home.

Lady DeLacy Ingham, third daughter, aged 12, living at home.

Lady Dulcie Ingham, fourth daughter, aged 5, the baby of the family, in care of the nanny.

The four girls are referred to affectionately as the four Dees by the staff.

OTHER INGHAMS

Lady Lavinia Ingham Lawson, married sister of the Earl, aged 40. She lives at Skelldale House, on the estate, when in Yorkshire. She is mostly in London. She is married to John Edward Lawson, known as Jack. He is a business tycoon.

Lady Vanessa Ingham, the spinster sister of the Earl, aged 34, who has her own private suite of rooms at Cavendon, which she uses when in Yorkshire. She spends most of her time in London.

Lady Gwendolyn Ingham Baildon, the widowed aunt of the Earl, aged 72, who resides at Little Skell Manor on the estate. She was married to the late Paul Baildon.

The Honourable Hugo Ingham Stanton, first cousin of the Earl, aged 32. He is the nephew of Lady Gwendolyn, the sister of his late mother, Lady Evelyne Ingham Stanton. He has been living abroad for years. His father was the late Ian Stanton, a racehorse breeder and owner.

BETWEEN STAIRS

THE SECOND FAMILY: THE SWANNS

The Swann family has been in service to the Ingham family for over one hundred and sixty years. Consequently, their lives have been intertwined in many different ways. Generations of Swanns have lived in Little Skell village, adjoining Cavendon Park, and still do. The present-day Swanns are as devoted and loyal to the Inghams as their forebears were, and would defend any member of the family with their lives. The Inghams trust them implicitly, and vice versa.

THE SWANNS IN 1913

Walter Swann, valet to the Earl, aged 35. Head of the Swann family.

Alice Swann, his wife, aged 32. A clever seamstress who takes care of the Countess’s clothes and makes outfits and frocks for the daughters.

Harry, son, aged 15. An apprentice landscape gardener at Cavendon Hall.

Cecily, daughter, aged 12, who is allowed to attend lessons at Cavendon Hall with DeLacy.

OTHER SWANNS

Percy, younger brother of Walter, aged 32. Head gamekeeper at Cavendon.

Edna, wife of Percy, aged 33. Does occasional work at Cavendon.

Joe, their son, aged 12. Works at Cavendon as a junior woodsman.

Bill, first cousin of Walter, aged 27. Head landscape gardener at Cavendon. He is unmarried.

Ted, first cousin of Walter, aged 38. Head of interior maintenance and carpentry at Cavendon. Widowed.

Paul, son of Ted, aged 14, apprenticed to his father as a designer.

Eric, brother of Ted, first cousin of Walter, aged 33. Butler at the London house of Lord Mowbray. Single.

Laura, sister of Ted, first cousin of Walter, aged 26. Housekeeper at the London house of Lord Mowbray. Single.

Charlotte, aunt of Walter and Percy, aged 45. Retired from service at Cavendon. Charlotte is the matriarch of the Swann family. She is treated with great respect by everyone, and with a certain deference by the Inghams. Charlotte was the secretary and personal assistant to David Ingham, the 5th Earl, until his death. There was some speculation about the true nature of their relationship.

Dorothy Pinkerton, née Swann, cousin of Charlotte and the Swanns. She lives in London and is married to Howard Pinkerton, a Scotland Yard detective.

CHARACTERS BELOW STAIRS

Mr Henry Hanson, Butler

Mrs Agnes Thwaites, Housekeeper

Mrs Nell Jackson, Cook

Miss Olive Wilson, Lady’s maid to the Countess

Mr Malcolm Smith, Head footman

Mr Gordon Lane, Second footman

Miss Elsie Roland, Head housemaid

Miss Mary Ince, Second housemaid

Miss Peggy Swift, Third housemaid

Miss Polly Wren, Kitchen maid

Mr Stanley Gregg, Chauffeur

OTHER EMPLOYEES

Miss Maureen Carlton, the nanny, usually addressed as Nanny or Nan.

Miss Audrey Payne, the governess, usually addressed as Miss Payne. The governess is not at Cavendon in the summer. The children are not in school.

THE OUTDOOR WORKERS

A great stately home such as Cavendon Hall, with thousands of acres of land, and a huge grouse moor, employs many local people. This is its purpose for being, as well as providing a private home for a great family. It offers employment to the local villagers, and also land for local tenant farmers. The villages surrounding Cavendon were built by various earls of Mowbray to provide housing for their workers; churches and schools were also built, as well as post offices and small shops at later dates. The villages around Cavendon are Little Skell, Mowbray and High Clough.

There are a great number of outside workers: a head gamekeeper and five additional gamekeepers; beaters and flankers who work when the grouse season starts. Other outdoor workers include woodsmen, who take care of the surrounding woods for shooting in the lowlands at certain times of the year. The gardens are cared for by a head landscape gardener, and five other gardeners working under him.

The grouse season starts in August, on the Glorious Twelfth, as it is called. It finishes in December. The partridge season begins in September. Duck and wild fowl are shot at this time. Pheasant shooting starts on 1 November and goes on until December. The men who come to shoot at Cavendon are usually aristocrats, and always referred to as the Guns, i.e., the men using the gun.

PART ONE

The Beautiful Girls of Cavendon May 1913

She is beautiful and therefore to be woo’d;

She is a woman, therefore to be won.

William Shakespeare

Honor women: They wreathe and weave

Heavenly roses into earthly life.

Johann von Schiller

Man is the hunter; woman is his game.

Alfred Tennyson

ONE

Cecily Swann was excited. She had been given a special task to do by her mother, and she couldn’t wait to start. She hurried along the dirt path, walking towards Cavendon Hall, all sorts of ideas running through her active young mind. She was going to examine some beautiful dresses, looking for flaws; it was an important task, her mother had explained, and only she could do it.

She did not want to be late, and increased her pace. She had been told to be there at ten o’clock sharp, and ten o’clock it would be.

Her mother, Alice Swann, often pointed out that punctuality might easily be her middle name, and this was always said with a degree of admiration. Alice took great pride in her daughter, and was aware of certain unique talents she possessed.

Although Cecily was only twelve, she seemed much older in some ways, and capable, with an unusual sense of responsibility. Everyone considered her to be rather grown up, more so than most girls of her age, and reliable.

Lifting her eyes, Cecily looked up the slope ahead of her. Towering on top of the hill was Cavendon, one of the greatest stately homes in England and something of a masterpiece.

After Humphrey Ingham, the 1st Earl of Mowbray, had purchased thousands of acres in the Yorkshire Dales, he had commissioned two extraordinary architects to design the house: John Carr of York, and the famous Robert Adam.

It was finished in 1761. Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown then created the landscaped gardens, which were ornate and beautiful, and had remained intact to this day. Close to the house was a manmade ornamental lake, and there were water gardens at the back of the house.

Cecily had been going to the hall since she was a small child, and to her it was the most beautiful place in the world. She knew every inch of it, as did her father, Walter Swann. Her father was valet to the Earl, just as his father had been before him, and his great-uncle Henry before that.

The Swanns of Little Skell village had been working at the big house for over one hundred and sixty years, generations of them, ever since the days of the 1st Earl in the eighteenth century. The two families were closely intertwined and bound together; the Swanns had many privileges, and were exceedingly loyal to the Inghams. Walter always said he’d take a bullet for the Earl, and meant it sincerely.

Hurrying along, preoccupied with her thoughts, Cecily was suddenly startled and stopped abruptly. A figure had jumped out onto the path in front of her, giving her a shock. Then she saw at once that it was the young gypsy woman called Genevra, who often lurked around these parts.

The Romany stood in the middle of the path, grinning hugely, her hands on her hips, her dark eyes sparkling.

‘You shouldn’t have done that!’ Cecily exclaimed, stepping sideways swiftly. ‘You startled me. Where did you spring from, Genevra?’

‘Yonder,’ the gypsy answered, waving her arm towards the long meadow. ‘I see yer coming, liddle Cecily. I wus behind t’wall.’

‘I have to get on. I don’t want to be late,’ Cecily said in a cool, dismissive voice. She tried to step around the young woman without success.

The gypsy dodged about, blocked her way, muttering, ‘Aye. Yer bound for that owld ’ouse up yonder. Gimme yer ’and and I’ll tell yer fortune.’

‘I can’t cross your palm with silver, I don’t even have a ha’penny,’ Cecily said.

‘I doan want yer money, and I’ve no need to see yer ’and, I knows all about yer.’

Cecily frowned. ‘I don’t understand …’ She let her voice drift off, impatient to be on her way, not wanting to waste any more time with the gypsy.

Genevra was silent, but she threw Cecily a curious look, then turned, stared up at Cavendon. Its many windows were glittering and the pale stone walls shone like polished marble in the clear northern light on this bright May morning. In fact, the entire house appeared to have a sheen.

The Romany knew this was an illusion created by the sunlight. Still, Cavendon did have a special aura about it. She had always been aware of that. For a moment she remained standing perfectly still, lost in thought, gazing at Cavendon … she had the gift, the gift of sight. And she saw the future. Not wanting to be burdened with this sudden knowledge, she closed her eyes, shutting it all out.

Eventually the gypsy swung back to face Cecily, blinking in the light. She stared at the twelve-year-old for the longest moment, her eyes narrowing, her expression serious.

Cecily was acutely aware of the gypsy’s fixed scrutiny, and said, ‘Why are you looking at me like that? What’s the matter?’

‘Nowt,’ the gypsy muttered. ‘Nowt’s wrong, liddle Cecily.’ Genevra bent down, picked up a long twig, began to scratch in the dirt. She drew a square, and then above the square she made the shape of a bird, then glanced at Cecily pointedly.

‘What do they mean?’ the child asked.

‘Nowt.’ Genevra threw the twig down, her black eyes soulful. And in a flash, her strange, enigmatic mood vanished. She began to laugh, and danced across towards the dry-stone wall.

Placing both hands on the wall, she threw her legs up in the air, cartwheeled over it and landed on her feet in the field beyond.

After she had adjusted the red bandana tied around her dark curls, she skipped down the long meadow and disappeared behind a copse of trees. Her laughter echoed across the stillness of the fields, even though she was no longer in sight.

Cecily shook her head, baffled by the gypsy’s odd behaviour, and bit her lip. Then she quickly scuffled her feet in the dirt, obliterating the gypsy’s symbols, and continued up the slope.

She’s always been strange, Cecily muttered under her breath, as she walked on. She knew that Genevra lived with her family in one of the two painted Romany wagons, which stood on the far side of the bluebell woods, way beyond the long meadow. She also knew that the Romany tribe was not trespassing.

It was the Earl of Mowbray’s land where they were camped, and he had given them permission to stay there in the warm weather. They always vanished in the winter months; where they went, nobody knew.

The Romany family had been coming to Cavendon for a long time. It was Miles who had told her that. He was the Earl’s second son, had confided that he didn’t know why his father was so nice to the gypsies. Miles was fourteen; he and his sister DeLacy were her best friends.

The dirt path through the fields led directly from Little Skell village to the back yard of Cavendon Hall. Cecily was running across the cobblestones of the yard when the clock in the stable-block tower began to strike the hour. It was exactly ten o’clock and she was not late.

Cook’s cheerful Yorkshire voice was echoing through the back door as Cecily stood for a moment, catching her breath, and listening.

‘Don’t stand there gawping like a sucking duck, Polly,’ Cook was exclaiming to the kitchen maid. ‘And for goodness’ sake, push the metal spoon into the flour jar before you add the lid. Otherwise we’re bound to get weevils in the flour!’

‘Yes, Cook,’ Polly muttered.

Cecily smiled to herself. She knew the reprimand didn’t mean much. Her father said Cook’s bark was worse than her bite, and this was true. Cook was a good soul, motherly at heart.

Turning the door-knob, Cecily went into the kitchen, to be greeted by great wafts of steam, warm air, and the most delicious smells emanating from the bubbling pans. Cook was already preparing lunch for the family.

Swinging around at the sound of the door opening, Cook smiled broadly when she saw Cecily entering her domain. ‘Hello, luv,’ she said in a welcoming way. Everyone knew that Cecily was her favourite; she made no bones about that.

‘Good morning, Mrs Jackson,’ Cecily answered and glanced at the kitchen maid. ‘Hello, Polly.’

Polly nodded, and retreated into a corner, as usual shy and awkward when addressed by Cecily.

‘Mam sent me to help with the frocks for Lady Daphne,’ Cecily explained.

‘Aye, I knows that. So go on then, luv, get along with yer. Lady DeLacy is waiting upstairs for yer. I understand she’s going to be yer assistant.’ As she spoke, Cook chuckled and winked at Cecily conspiratorially.

Cecily laughed. ‘Mam will be here about eleven.’

The cook nodded. ‘Yer’ll both be having lunch down here with us. And yer father. A special treat.’

‘That’ll be nice, Mrs Jackson.’ Cecily continued across the kitchen, heading for the back stairs that led to the upper floors of the great house.

Nell Jackson watched her go, her eyes narrowing slightly. The twelve-year-old girl was lovely. Suddenly, she saw in that innocent young face the woman she would become. A real beauty. And a true Swann. No mistaking where she came from, with those high cheekbones, ivory complexion and the lavender eyes … Pale, smoky, bluish-grey eyes. The Swann trademark. And then there was that abundant hair. Thick, luxuriant, russet-brown, shot through with reddish lights. She’ll be the spitting image of Charlotte when she grows up, Cook thought, and sighed to herself. What a wasted life she’d had, Charlotte Swann. She could have gone far, no two ways about that. I hope the girl doesn’t stay here, like her aunt did, Nell now thought, turning around, stirring one of her pots. Run, Cecily, run. Run for your life. And don’t look back. Save yourself.

TWO

The library at Cavendon was a beautifully proportioned room. It had two walls of high-soaring mahogany bookshelves, reaching up to meet a gilded coffered ceiling painted with flora and fauna in brilliant colours. A series of tall windows faced the long terrace that stretched the length of the house. At each end of the window wall were French doors.

Even though it was May, and a sunny day, there was a fire burning in the grate, as there usually was all year round. Charles Ingham, the 6th Earl of Mowbray, was merely following the custom set by his grandfather and father before him. Both men had insisted on a fire in the room, whatever the weather. Charles fully understood why. The library was the coldest room at Cavendon, even in the summer months, and this was a peculiarity no one had ever been able to fathom.

This morning, as he came into the library and walked directly towards the fireplace, he noticed that a George Stubbs painting of a horse was slightly lopsided. He went over to straighten it. Then he picked up the poker and jabbed at the logs in the grate. Sparks flew upwards, the logs crackled, and after jabbing hard at them once more, he returned the poker to the stand.

Charles stood for a moment in front of the fire, his hand resting on the mantelpiece, caught up in his thoughts. His wife Felicity had just left to visit her sister in Harrogate, and he wondered again why he had not insisted on accompanying her. Because she didn’t want you to go, an internal voice reminded him. Accept that.

Felicity had taken their eldest daughter Diedre with her. ‘Anne will be more at ease, Charles. If you come, she will feel obliged to entertain you properly, and that will be an effort for her,’ Felicity had explained at breakfast.

He had given in to her, as he so often did these days. But then his wife always made sense. He sighed to himself, his thoughts focused on his sister-in-law. She had been ill for some time, and they had been worried about her; seemingly she had good news to impart today, and had invited her sister to lunch to share it.

Turning away from the fireplace, Charles walked across the Persian carpet, making for the antique Georgian partners’ desk, and sat down in the chair behind it.

Thoughts of Anne’s illness lingered, and then he reminded himself how practical and down-to-earth Diedre was. This was reassuring. It struck him that at twenty Diedre was probably the most sensible of his children. Guy, his heir, was twenty-two, and a relatively reliable young man, but unfortunately he had a wild streak that sometimes reared up. It worried Charles.