Полная версия

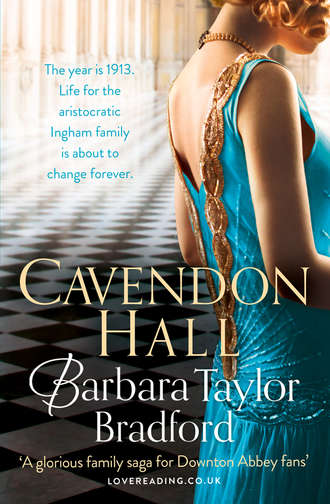

Cavendon Hall

Miles, of course, was the brains in the family; he had something of an intellectual bent, even though he was only fourteen, and artistic. He never worried about Miles. He was utterly loyal: true blue.

And then there were his other three daughters. Daphne, at seventeen, the great beauty of the family. A pure English rose, with looks to break any man’s heart. He had grand ambitions for his Daphne. He would arrange a great marriage for her. A duke’s son, nothing less.

Her sister DeLacy was the most fun, if he was truthful; quite a mischievous twelve-year-old. Charles was aware she had to grow up a bit, and unexpectedly a warm smile touched his mouth. DeLacy always managed to make him laugh, and entertained him with her comical antics. His last child, five-year-old Dulcie, was adorable; much to his astonishment, she was already a person in her own right, with a mind of her own.

Lucky, I’ve been lucky, he thought, reaching for the morning’s post. Six lovely children, all of them quite extraordinary in their own way. I have been blessed, he reminded himself. Truly blessed with my wife and this admirable family we’ve created. I am the most fortunate of men.

As he shuffled through the post, one envelope in particular caught his eye. It was postmarked Zurich, Switzerland. Puzzled, he slit the envelope with a silver opener, and took out the letter.

When he glanced at the signature, Charles was taken aback. The letter had been written by his first cousin, Hugo Ingham Stanton. He hadn’t heard from Hugo since he had left Cavendon at sixteen, although Hugo’s father had told Charles his son had fared well in the world. He had often wondered about what had become of Hugo. No doubt he was about to find out now.

April 26th, 1913

Zurich

My dear Charles,

I am sure that you will be surprised to receive this letter from me after all these years. However, because I left Cavendon in the most peculiar circumstances, and at such odds with my mother, I decided it would be better if I cut all contact with the family at that time. Hence my long silence.

I continued to see my father until the day he died. No one else wrote to me in New York, and I therefore did not have the heart to put pen to paper. And so years have passed without contact.

I will not bore you with a long résumé of my life for the past sixteen years. Suffice it to say that I did well, and I was particularly lucky that Father sent me to his friend, Benjamin Silver. I became an apprentice in Mr Silver’s real-estate company in New York. He was a good man, and brilliant. He taught me everything there was to learn about the real-estate business, and, I might add, he taught me well.

I acquired invaluable knowledge, and, much to my own surprise, I was a success. When I was twenty-two I married Mr Silver’s daughter, Loretta. We had a very happy union for nine years, but sadly there were no children. Always fragile in health, Loretta died here in Zurich a year ago, much to my sorrow and distress. For the past year, since her passing, I have continued to live in Zurich. However, loneliness has finally overtaken me, and I have a longing to come back to the country of my birth. And so I have now made the decision to return to England.

I wish to reside in Yorkshire on a permanent basis. For this reason I would like to pay you a visit, and sincerely hope that you will receive me cordially at Cavendon. There are many things I wish to discuss with you, and most especially the property I own in Yorkshire.

I am planning to travel to London in June, where I shall take up residence at Claridge’s Hotel. Hopefully I can visit you in July, on a date that is convenient to you.

I look forward to hearing from you in the not-too-distant future. With all good wishes to you and Felicity.

Sincerely, your Cousin,

Hugo

Charles leaned back in the chair, still holding the letter in his hand. Finally, he placed it on the desk, and closed his eyes for a moment, thinking of Little Skell Manor, the house which had belonged to Hugo’s mother, and which he now owned. No doubt Hugo wanted to take possession of it, which was his legal right.

A small groan escaped him, and Charles opened his eyes and sat up in the chair. No use turning away from the worries flooding through him. The house was Hugo’s property. The problem was that their aunt, Lady Gwendolyn Ingham Baildon, resided there, and at seventy-two years old she would dig her feet in if Hugo endeavoured to turf her out.

The mere thought of his aunt and Hugo doing battle sent an icy chill running through Charles, and his mind began to race as he sought a solution to this difficult situation.

Finally he rose, walked over to the French doors opposite his desk, and stood looking out at the terrace, wishing Felicity were here. He needed somebody to talk to about this problem. Right away.

Then he saw her, hurrying down the steps, making for the wide gravel path that led to Skelldale House. Charlotte Swann. The very person who could help him. Of course she could.

Without giving it another thought, Charles stepped out onto the terrace. ‘Charlotte!’ he called. ‘Charlotte! Come back!’

On hearing her name, Charlotte instantly turned around, her face filling with a smile when she saw him. ‘Hello,’ she responded, lifting her hand in a wave. As she did this she began to walk back up the terrace steps. ‘Whatever is it?’ she asked when she came to a stop in front of him. Staring up into his face, she said, ‘You look very upset … is something wrong?’

‘Probably,’ he replied. ‘Could you spare me a few minutes? I need to show you something, and to discuss a family matter. If you have time, if it’s not inconvenient now. I could—’

‘Oh Charlie, come on, don’t be silly. Of course it’s not inconvenient. I was only going to Skelldale House to get a frock for Lavinia. She wants me to send it to London for her.’

‘That’s a relief. I’m afraid I have a bit of a dilemma.’ Taking her arm, he led her into the library, continuing, ‘What I mean is, something has happened that might become a dilemma. Or even a battle royal.’

THREE

When they were alone together, there was an easy familiarity between Charles Ingham and Charlotte Swann.

This unselfconscious acceptance of each other sprang from their childhood friendship, and a deeply ingrained loyalty that had remained intact over the years.

Charlotte had grown up with Charles and his two younger sisters, Lavinia and Vanessa, and had been educated with them by the governess who was in charge of the schoolroom at Cavendon Hall at that time.

This was one of the privileges bestowed on the Swanns over a hundred years earlier, by the 3rd Earl of Mowbray: A Swann girl was invited to join the Ingham children for daily lessons. The 3rd Earl, a kind and charitable man, respected the Swanns, appreciated their dedication and loyalty to the Inghams through the generations, and it was his way of rewarding them. The custom had continued up to this very day, and it was now Cecily Swann who went to the schoolroom with DeLacy Ingham for their lessons with Miss Audrey Payne, the governess.

When they were little, Charlotte and Charles had enjoyed irking his sisters by calling each other Charlie, chortling at the confusion this created. They had been inseparable until he had gone off to Eton. Nevertheless, their loyalty and concern for each other had lasted over the years, albeit in a slightly different way. They didn’t mingle or socialize once Charles had gone to Oxford, and, in fact, they lived in entirely different worlds. When they were with his family, or other people, they addressed each other formally, and were respectful.

But it existed still, that childhood bond, and they were both aware of their closeness, although it was never referred to. He had never forgotten how she had mothered him, looked out for him when they were small. She was only one year older than he was, but it was Charlotte who took charge of them all.

She had comforted him and his sisters when their mother had suddenly and unexpectedly died of a heart attack; commiserated with them when, two years later, their father had remarried. The new Countess was the Honourable Harriette Storm, and they all detested her. The woman was snobbish, brash and bossy, and had a mean streak. She had trapped the grief-stricken Earl, who was lonely and lost, with her unique beauty, which Charlotte loved to point out was only skin deep, after all.

They had enjoyed playing tricks on her, the worse the better, and it was Charlotte who had come up with a variety of names for her: Bad Weather, Hurricane Harriette and Rainy Day, to name just three of them. The names made them laugh, had helped them to move on from the rather childish pranks they played. Eventually they simply poked fun at her behind her back.

The marriage had been abysmal for the Earl, who had retreated behind a carapace of his own making. And it had not lasted long. Hateful Harriette soon returned to London. It was there that she died, not long after her departure from Cavendon. Her liver failed because it had been totally destroyed by the huge quantities of alcohol she had consumed since her debutante days.

Charles suddenly thought of the recent past as he stood watching Charlotte straightening the horse painting by George Stubbs, remembering how often she had done this when she had worked for his father.

With a laugh, he said, ‘I just did the same thing a short while ago. That painting’s constantly slipping, but then I don’t need to tell you that.’

Charlotte swung around. ‘It’s been re-hung numerous times, as you well know. I’ll ask Mr Hanson for an old wine cork again, and fix it properly.’

‘How can a wine cork do that?’ he asked, puzzled.

Walking over to join him, she explained, ‘I cut a slice of the cork off and wedge it between the wall and the bottom of the frame. A bit of cork always holds the painting steady. I’ve been doing it for years.’

Charles merely nodded, thinking of all the bits of cork he had been picking up and throwing away for years. Now he knew what they had been for.

Motioning to the chair on the other side of the desk, he said, ‘Please sit down, Charlotte, I need your advice.’

She did as he asked, and glanced at him as he sat down himself, thinking that he was looking well. He was forty-four, but he didn’t look it. Charles was athletic, as his father had been, and kept himself in shape. Like most of the Ingham men, he was tall, attractive, had their clear blue eyes, a fair complexion and light brown hair. Wherever he went in the world, she was certain nobody would mistake him for being anything but an Englishman. And an English gentleman at that. He was refined looking, had a classy air about him, and handled himself with a certain decorum.

Leaning across the desk, Charles handed Charlotte the letter from Hugo. ‘I received this in the morning post and, I have to admit, it genuinely startled me.’

She took the letter from him, wondering who had sent it. Charlotte had a quick mind, was intelligent and astute. And having worked as the 5th Earl’s personal assistant for years, there wasn’t much she didn’t know about Cavendon, and everybody associated with it. She was not at all surprised when she saw Hugo’s signature; she had long harboured the thought that this particular young man would show up at Cavendon one day.

After reading the letter quickly, she said, ‘You think he’s coming back to claim Little Skell Manor, don’t you?’

‘Of course. What else?’

Charlotte nodded in agreement, and then frowned, and pursed her lips. ‘But surely Cavendon is full of unhappy memories for him?’

‘I would think that’s so; on the other hand, as you’ve seen, Hugo says in his letter that he wishes to discuss the property he owns here, and also informs me that he plans to live in Yorkshire permanently.’

‘At Little Skell Manor. And perhaps he doesn’t care that he will have to turn an old lady out of the house she has lived in for donkey’s years, long before his parents died, in fact.’

‘Quite frankly, I don’t know. I haven’t laid eyes on him for sixteen years. Since he was sixteen, actually. However, he must be fully aware that our aunt still lives there.’ Charles threw her a questioning look, raising a brow.

‘It’s quite easy to check on this well-known family, even long-distance,’ Charlotte asserted. Sitting back in the chair, she was thoughtful for a moment. ‘I remember Hugo. He was a nice boy. But he might well have changed, in view of what happened to him here. He was treated badly. You must recall how angry your father was when his sister sent Hugo off to America.’

‘I do,’ Charles replied. ‘My father thought it was ridiculous. He didn’t believe Hugo caused Peter’s death. Peter had always been a risk-taker, foolhardy. To go out on the lake here, in a little boat, late at night when he was drunk, was totally irresponsible. My father always said Hugo tried to rescue his brother, to save him, and then got blamed for his death.’

‘We mustn’t forget that Peter was Lady Evelyne’s favourite. Your aunt never paid much attention to Hugo. It was sad. A tragic affair, really.’

Charles leaned forward, resting his elbows on the desk. ‘You know how much I trust your judgement. So tell me this – what am I going to do? There will be an unholy row, a scandal, if Hugo does take back the manor. Which of course he can, legally. What happens to Aunt Gwendolyn? Where would she live? With us here in the East Wing? That’s the only solution I can come up with.’

Charlotte shook her head vehemently. ‘No, no, that’s not a solution! It would be very crowded with you and Felicity, and six children, and your sister Vanessa. Then there’s the nanny, the governess, and all the staff. It would be like … well … a hotel. At least to Lady Gwendolyn it would. She’s an old lady, set in her ways, independent, used to running everything. By that I mean her own household, with her own staff. And she’s fond of her privacy.’

‘Possibly you’re right,’ Charles muttered. ‘She’d be aghast.’

Charlotte went on, ‘Your aunt would feel like … a guest here, an intrusion. And I believe she would resent being bundled in here with you, with all due respect, Charles. In fact, she’ll put up a real fight, I fear, because she’ll be most unhappy to leave her house.’

‘It isn’t hers,’ Charles said softly. ‘Pity her sister Evelyne never changed her will. My aunt will have to move. There’s no way around that.’ He sat back in the chair, a gloomy expression settling on his face. ‘I do wish Cousin Hugo wasn’t planning to come back and live here. What a blasted nuisance this is.’

‘I don’t want to make matters worse,’ Charlotte began, ‘but there’s another thing. Don’t—’

‘What are you getting at?’ he interrupted swiftly, alarm surfacing. He sat up straighter in the chair.

‘We know Lady Gwendolyn will be put out, but don’t you think Hugo’s presence on the estate is going to upset some other people as well? There are still those who think Hugo was responsible for Peter’s death, and—’

‘That’s because they don’t know the facts,’ he cut in sharply. ‘Or they won’t accept them.’

Charlotte remained silent, her mind racing.

Getting up from the chair, Charles walked over to the fireplace, stood with his back to it, imagining worrying scenarios. He still thought the only way to deal with this matter easily and in a kindly way was to invite his aunt to live with them. Perhaps Felicity could talk to her. His wife had a rather persuasive manner and much charm.

Charlotte stood up, and joined him near the fireplace. As she approached him she couldn’t help thinking how much he resembled his father in certain ways. He had inherited some of his father’s mannerisms, often sounded like him.

Instantly her mind turned to David Ingham, the 5th Earl of Mowbray. She had worked for him for twenty years, until he had died. Eight years ago now. As those happy days, still so vivid, came into her mind, she thought of the South Wing at Cavendon. It was there they had worked, alongside Mr Harris, the accountant, Mr Nelson, the estate manager, and Maude Greene, the secretary.

‘The South Wing, that’s where Lady Gwendolyn could live!’ Charlotte blurted out as she came to a stop next to Charles.

‘Those rooms Father used as offices? Where you worked?’ he asked, and then a wide smile spread across his face. ‘Charlotte, you’re a genius. Of course she could live there. And very comfortably.’

Charlotte nodded, and hurried on, her enthusiasm growing. ‘Your father put in several bathrooms and a small kitchen, if you remember. When you built the office annexe in the stable block, all of the office furniture was moved over there. The sofas, chairs and drawing-room furniture came down from the attics and into the South Wing.’

‘Exactly. And I know the South Wing is constantly well maintained by Hanson and Mrs Thwaites. Every wing of Cavendon is kept in perfect condition, as you’re aware.’

‘If Lady Gwendolyn agreed, she would have a self-contained flat, in a sense, and total privacy,’ Charlotte pointed out.

‘That’s true, and I would be happy to make as many changes as she wished.’ Taking hold of her arm, he continued, ‘Let’s go and look at those rooms in the South Wing, shall we? You do have time, don’t you?’

‘I do, and that’s a good idea, Charles,’ she responded. ‘Because you have no alternative but to invite Hugo Stanton to visit Cavendon. And I think you must be prepared for the worst. He might well want to take possession of Little Skell Manor immediately.’

His chest tightened at her words, but he knew she was right.

As they moved through the various rooms in the South Wing, and especially those that his father had used as offices, Charles thought of the relationship between his father and Charlotte.

Had there been one?

She had come to work for him when she was a young girl, seventeen, and she had been at the 5th Earl’s side at all times, had travelled with him, and been his close companion as well as his personal assistant. It was Charlotte who had been with his father when he died.

Charles was aware there had been speculation about their relationship, but never any real gossip. No one knew anything. Perhaps this was due to total discretion on his father’s part and Charlotte’s … that there was not a whiff of a scandal about them.

He glanced across at Charlotte. They were in the lavender room, and she was explaining to him that his aunt might like to have it as her bedroom. He was only half listening.

A raft of brilliant spring sunshine was slanting into the room, was turning her russet hair into a burnished helmet around her face. As always, she was pale, and her light greyish-blue eyes appeared enormous. For the first time in years, Charles saw her objectively. And he realized what a beautiful woman she was; she looked half her true age.

Thrown into her company every day for twenty years, how could his father have ever resisted her? Charles Ingham was now positive they had been involved with each other. And on every level.

It was an assumption on his part. There was no evidence. Yet at this moment it had suddenly become patently obvious to him. Charles had grown up with his father and Charlotte, and knew them better than anyone, even better than his wife Felicity, and he certainly knew her very well indeed. And he had had insight into them, had been aware of their flaws and their attributes, dreams and desires; and so he believed, deep in his soul, that it was more than likely they had been lovers.

Charles turned away, realizing he had been staring so hard she had become aware of his penetrating scrutiny. Moving quickly, saying something about the small kitchen, he hurried out of the lavender room into the corridor.

And why does all this matter now? he asked himself. His father was dead. And if Charlotte had made him happy, and eased his burdens, then he was glad. Charles hoped they had loved each other.

But what about Charlotte? How did she feel these days? Did she miss his father? Surely she must. All of a sudden he was filled with concern for her. He wanted to ask her how she felt. But he didn’t dare. It would be an unforgivable intrusion on her privacy, and he had no desire to embarrass her.

FOUR

The evening gown lay on a white sheet, on the floor of Lady DeLacy Ingham’s bedroom. DeLacy was the twelve-year-old daughter of the Earl and Countess, and Cecily’s best friend. This morning she was excited, because she had been allowed to help Cecily with the dresses. These had been brought down from the large cedar storage closet in the attics. Some were hanging in the sewing room, awaiting Alice’s inspection; two others were here.

The gown that held their attention was a shimmering column of green, blue and turquoise crystal beads, and to the two young girls kneeling next to it, the dress was the most beautiful thing they had ever seen.

‘Daphne’s going to look lovely in it,’ DeLacy said, staring across at Cecily. ‘Don’t you think so?’

Cecily nodded. ‘My mother wants me to seek out flaws in the dress, such as broken beads, broken threads, any little problems. She needs to know how many repairs it needs.’

‘So that’s what we’ll do,’ DeLacy asserted. ‘Shall I start here? On the neckline and the sleeves?’

‘Yes, that’s a good idea,’ Cecily answered. ‘I’ll examine the hem, which my mother says usually gets damaged by men. By their shoes, I mean. They all step on the hem when they’re dancing.’

DeLacy nodded. ‘Clumsy. That’s what they are,’ she shot back, always quick to speak her mind. She was staring down at the dress, and exclaimed, ‘Look, Ceci, how it shimmers when I touch it.’ She shook the gown lightly. ‘It’s like the sea, like waves, the way it moves. It will match Daphne’s eyes, won’t it? Oh, I do hope she meets a duke’s son when she’s wearing it.’

‘Yes,’ Cecily muttered absently, her head bent as she concentrated on the hemline of the beaded gown. It had been designed and made in Paris by a famous designer, and the Countess had only worn it a few times. Then it had been carefully stored, wrapped in white cotton and placed in a large box. The gown was to be given to Daphne, to wear at one of the special summer parties, once it had been fitted to suit her figure.

‘There’s hardly any damage,’ Cecily announced a few minutes later. ‘How are the sleeves and the neckline?’

‘Almost perfect,’ DeLacy replied. ‘There aren’t many beads missing.’

‘Mam will be pleased.’ Cecily stood up. ‘Let’s put the gown back on the bed.’

She and DeLacy took the beaded evening dress, each of them holding one end, and lifted it carefully onto DeLacy’s bed. ‘Gosh, it’s really heavy,’ she said as they put it back in place.

‘That’s the reason beaded dresses are kept in boxes or drawers,’ Cecily explained. ‘If a beaded gown is put on a hanger, the beads will eventually weigh it down, and that makes the dress longer. It gets out of shape.’

DeLacy nodded, always interested in the things Cecily told her, especially about frocks. She knew a lot about clothes, and DeLacy learned from her all the time.

Cecily straightened the beaded dress and covered it with a long piece of cotton, then walked across the room to look out of the window. She was hoping to see her mother coming from the village. There was no sign of her yet.

DeLacy remained near the bed, now staring down at the other summer evening gown, a froth of white tulle, taffeta and handmade lace. ‘I think I like this one the most,’ she said to Cecily without turning around. ‘This is a real ball gown.’

‘I know. Mam told me your mother wore it only once, and it’s been kept in a cotton bag in the cedar closet for ages. That’s why the white is still white. It hasn’t turned.’