Полная версия

Lost in Babylon

Fiddle looked impressed. “You go, girl.”

“Whaaat? That’s impossible!” Cass shook his head in disbelief, then glanced at Professor Bhegad uncertainly. “Isn’t it?”

I desperately tried to remember something weird I once learned. “In science class … when I wasn’t sleeping … my teacher was talking about this famous theory. She said to imagine you were in a speeding train made of glass, and you threw a ball up three feet and then caught it. To you, the ball’s going up and down three feet. But to someone outside the train, looking through those glass walls …”

“The ball moves in the direction of the train, so it travels many more than three feet—not just up and down, but forward,” Professor Bhegad said. “Yes, yes, this is the theory of special relativity …”

“She said time could be like that,” I went on. “So, like, if you were in a spaceship, and you went really fast, close to the speed of light, you’d come back and everyone on earth would be a lot older. Because, to them, time is like that ball. It goes faster when it’s just up and down instead of all stretched out.”

“So you’re thinking you guys were like the spaceship?” Nirvana said. “And that place we found—it’s like some parallel world going slower, alongside our world?”

“But if we both exist at the same time, why aren’t we seeing them?” Marco said. “They should be on the other side of the river, only moving really slow a-a-a-a-a-n-n-n-d speeeeeeeeaki-i-i-i-i-ing l-i-i-i-ke thi-i-i-i-s …”

“We have five senses and that’s all,” Aly said. “We can see, hear, touch, smell, taste. Maybe when you bend time like that, the rules are different. You can’t experience the other world, at least with regular old physical senses.”

“But you—you all managed to traverse the two worlds,” Bhegad said, “by means of some—”

“Portal,” Fiddle piped up.

“It looked like a tire,” Marco said. “Only nicer. With cool caps.”

Bhegad let out a shriek. “Oh! This is extraordinary. Revolutionary. I must think about this. I’ve been postulating the existence of wormholes all my life.”

Torquin raised a skeptical eyebrow. “Pustulate not necessary. See wormholes every day!”

“A wormhole in time,” Bhegad said. “It’s where time and space fold in on themselves. So the normal rules don’t apply. The question is, what rules do apply? These children may very well have traveled cross-dimensionally. They saw a world that occupies this space, this same part of the earth where we now stand. How does one do this? The only way is by traveling through some dimensional flux point. In other words, one needs to find a disruption in the forces of gravity, magnetism, light, atomic attraction.”

“Like the portal in Mount Onyx,” I said, “where the griffin came through.”

“Exactly,” Professor Bhegad said. “Do you realize what you were playing with? What dangers you risked? According to the laws of physics, your bodies could have been turned inside out … vaporized!”

I shrugged. “Well, I’m feeling pretty good.”

“You told me you could feel the Loculus, Jack,” Bhegad said. “The way you felt the Heptakiklos in the volcano.”

“I felt it, too,” Marco said. “We’re Select, yo. We get all wiggy when we’re near this stuff. It’s a G7W thing.”

“Which means, unfortunately, you will have to return …” Bhegad stated, his voice drifting off as he sank into thought.

“Yeah, and this time without the twenty-first-century clothes, which make us stick out,” Marco said. “I say we hit the nearest costume shop, buy some stylish togas, and go back for the prize.”

“Not togas,” Aly said. “Tunics.”

Professor Bhegad shook his head. “Absolutely not. This is not to be rushed into. We must return to our original plan, to finish your training. Recent events—the vromaski, the griffin—they forced our hand. Made us rush. They thrust you into an adventure for which you were not adequately prepared …”

“Old school … old school …” Marco chanted.

“Call it what you wish, but I call it prudent,” Professor Bhegad shot back. “Everything you’ve done—Loculus flying, wormhole traveling—is unprecedented in human history. We need to study the flight Loculus. Consult our top scientists about further wormhole visits. Assess risk. If and when you go back through the portal, we must have a plan—safety protocols, contingencies, strategies, precise timing to your treatment schedule. Now, turn me around so we can get started.”

Fiddle threw us a shrug and then began turning the old man back toward the tents.

“Yo, P. Beg—wait!” Marco said.

Professor Bhegad stopped and looked over his shoulder. “And that’s another thing, my boy—it’s Professor Bhegad. Sorry, but you will not be calling the shots anymore. From here on, you are on a tight leash.”

“Um, about that flight Loculus?” Marco said. “Sorry, but you can’t study it.”

Professor Bhegad narrowed his eyes. “You said you hid it, right?”

“Uh, yeah, but—” Marco began.

“Then retrieve it!” Bhegad snapped.

Marco rubbed the back of his neck, looking out toward the water. “The thing is—I hid it … there.”

“In the water?” Nirvana asked.

“No,” Marco replied. “Over in the other place.”

Bhegad slumped. “Well, this makes the job a bit more complicated, doesn’t it? I suppose you do have to go sooner rather than later. Prepared or not. Perhaps I will have to send the able-bodied Fiddle along to help you.”

“Or Torquin,” Torquin grunted indignantly, “who is able-bodied … er.”

Fiddle groaned. “This is not in my job description. Or Tork’s. We were told one Loculus in each of the Seven Wonders. Not in some fantasy time warp—in the real world.”

“The second Loculus, dear Fiddle,” Bhegad said, “is indeed in one of the Wonders.”

“Right—so we should be digging, not spinning sci-fi stories,” Fiddle said. “You see those ruins down the river—that’s where the Hanging Gardens were!”

“But our Select have gone to where the Hanging Gardens are.” Bhegad gestured toward the water, his eyes shining. “I believe they have found the ancient city of Babylon.”

“Check,” said Nirvana. “Soaked in the river and dried out, for that ancient worn-in look. And you have no idea how hard it was to find size thirteen double E, for Mr. Hoopster.”

“Sorry,” Marco said sheepishly. “Big feet mean a big heart.”

“Oh, please,” Fiddle said with a groan.

“Tunics?” Bhegad pressed onward. “Hair dye to cover up the lambdas? Can’t let the Babylonians see them, you know. Their time frame is close to the time of the destruction of Atlantis, almost three millennia ago. The symbol might mean something to them.”

“Do a pirouette, guys,” Nirvana said.

We turned slowly, showing Bhegad the dye job Nirvana had done to the backs of our heads. “It was a little hard to match the colors,” Nirvana said. “Especially with Jack. There’s all this red streaked in with the mousy brown, and I had to—”

“If I need further information, I’ll ask!” Bhegad snapped.

“Well, excuuuuuse me for talking.” Nirvana folded her arms and plopped down on the floor of the tent, not far from where I was studying.

We were feverishly trying to learn as much as we could about Babylon and the Hanging Gardens. Professor Bhegad had been tense and demanding over the last couple of days. “Ramsay!” he barked. “Why were the Gardens built?”

“Uh … I know this … because the king dude wanted to make his wife happy,” Marco said. “She was from a place with mountains and stuff. So the king was like, ‘Hey babe, I’ll build you a whole mountain right here in the desert, with flowers and cool plants.’”

“Williams!” Bhegad barked. “Tell me the name of the, er, king dude—as you so piquantly call it—who built the Hanging Gardens. Also, the name of the last king of Babylon.”

“Um …” Cass said, sweat pouring down his forehead. “Uh …”

“Nebuchadnezzar the Second and Nabonidus!” Bhegad closed his eyes and removed his glasses, slowly massaging his forehead with his free hand. “This is hopeless …”

Cass shook his head. He looked like he was about to cry. “I should have known that. I’m losing it.”

“You’re not losing it, Cass,” I said.

“I am,” he replied. “Seriously. Something is wrong with me. Maybe my gene is mutating. This could really mess all of us up—”

“I will give you a chance to redeem yourself, Williams,” Bhegad said. “Give me the names the Babylonians actually called Nebuchadnezzar and Nabonidus. Come now, dig deep!”

Cass spun around. “What? I didn’t hear that—”

“Nabu-Kudurri-Usur and Nabu-na’id!” Bhegad said. “Don’t forget that! How about Nabu-na’id’s evil son? Marco, you take a turn!”

“Nabonudist Junior?” Marco said.

“Belshazzar!” Bhegad cried out in frustration. “Or Bel-Sharu-Usur! Hasn’t anyone been paying attention?”

“Give us a break, Professor, these are hard to remember!” Aly protested.

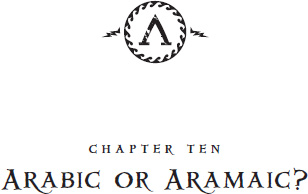

“You need to know these people cold—what if you meet them?” Bhegad said. “Black—what was the main language spoken?”

“Arabic?” Aly said.

Bhegad wiped his forehead. “Aramaic—Aramaic! Along with many other languages. Many nationalities lived in Babylon, each with a different language—Anatolians, Egyptians, Greeks, Judaeans, Persians, Syrians. The great central temple of Etemenanki was also known as the …?”

“Tower of Lebab—aka Babel!” Cass blurted out. “Which is where we get the term babble! Because people gathered around it and talked and prayed a lot.”

“Cass will fit right in,” Marco said, “speaking Backwardish.”

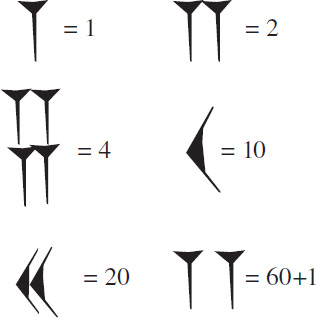

Bhegad tapped the table impatiently. “Next I quiz you on the numerical system.” He plopped down a sheet of paper with all kinds of gobbledygook scribbled on it:

“Memorize these numbers,” Bhegad said. “Remember, our columns are ones, tens, hundreds, et cetera. Theirs were one, sixty, thirty-six hundred, et cetera.”

“Can you go slowly,” Marco said. “Like we have normal intelligence?”

“Those, my boy,” Bhegad said, pronouncing each word exaggeratedly, “may perhaps resemble bird prints to you, but they’re numbers. Start from that fact … and read! We will have a moment of silence while you attempt to learn. And I attempt to settle my roiling stomach.”

As Fiddle pulled him back toward a table where his medicines were set up, I slid down to the ground with a book in hand, next to a pouting Nirvana. “Dang, what did he eat for breakfast?” she mumbled.

“He’s just worried, that’s all,” I said. “About us being in a wormhole.”

Across the tent, Cass and Aly huddled over a tablet, studying research documents the professor had downloaded—histories, ancient–language study manuals, reports on social behavior norms. “Okay, so the upper class dudes were awilum,” Cass was saying, “the lower class was mushkenum, and the slaves were …”

“Wardum,” Aly replied. “Like wards of the state. You can remember it that way.”

“Mud-raw backward,” Cass said. “That’s easier.”

“What? Mud-raw?” Marco slapped the table. “This is ridiculous. Yo, P. Beg, this isn’t Princeton. We can’t learn the entire history of Babylon in two days. We’re not going there to live. Let’s just pop over and bring this thing back.”

I thought Professor Bhegad would freak. For a moment his face went beet red. Then he sighed, removing his glasses and wiping his forehead. “You know, in the Mahabharata, the Hindus wrote of a king who made a rather quick journey to heaven. When he returned the world had aged many years, people were feeble and small. Their brains had rotted away.”

“So wait, we’re like that king?” Marco said. “And you’re the world?”

“It’s a metaphor,” Bhegad said.

“I never metaphor I didn’t like,” Marco said, “but dude, your brain won’t rot away. It’s preserved in awesome.”

“I may be dead by the time you return. I am concerned about the passage of time. And I do have a plan.” Bhegad looked each of us in the eye, one by one. “I am giving you forty-eight hours. That will be six months for us. We will continue to maintain a camp here and wait patiently for the five of you. If you are as marvelous as we think you are, that will be enough time to find both Loculi. When the time is up, no matter what happens, you will return. If you need another voyage, we will plan it then. Understood?”

“Wait—you said the five of us,” I said warily. “Fiddle is coming?”

“No, you need protection, first and foremost,” Professor Bhegad looked at Torquin. “Don’t lose them this time, my barefooted friend. And keep yourself out of jail.”

* * *

“Step … step … step … step …”

Torquin called out marching orders like a drill sergeant. He had tied us together at the waist with long lengths of rope, which dragged on the sand between us as we walked. We were lined up left to right—Marco, Aly, Torquin, Cass, and me.

“Is this necessary?” Aly asked as we reached water’s edge.

“Safety,” Torquin said. “I lose you, I lose job.”

I glanced over my shoulder. Professor Bhegad, Nirvana, and Fiddle were waiting and watching, near a big, domed tent.

“Who wants to go first?” I asked.

With a sly grin, Marco lunged for the water like a sprinter. His rope pulled Aly forward, then Torquin, Cass, and me. Torquin bellowed something I can’t repeat.

I felt myself go under, floundering helplessly. Being tied to Torquin wasn’t a help. His flailing arms smacked against me like boards.

Don’t fight the water. It’s your friend. That was Mom’s voice—from way back during my first, terrifying swim lesson at the Y. I could barely remember what she sounded like, but I felt her words giving me strength. I let my muscles slacken. I let Marco’s body pull me. And then I swam in his direction.

Soon I was passing Torquin. The rope’s slack was long enough so I could open up some distance. I could see Aly’s feet just ahead of me, kicking hard. Her rope was nearly taut to Torquin. She was holding tight to Cass, who chopped the water as best as he could.

There. The circle of tiles, just below us. The strange music began seeping into my brain.

This is going to hurt. Don’t fight it.

I braced myself. I let my body go. I felt the sudden expanding and contracting. Like I was going to explode.

It hurt just as much, felt just as inhuman. But it was the second time, and I was more ready than I expected. I blasted through the other side of the circle, my lungs nearly bursting, my body looser and prepared for the cold.

I was not, however, prepared to be yanked backward.

My rope was taut.

Torquin.

Was this some kind of joke? Was he stuck?

I turned. Torquin had not emerged. It was as if he were pulling me back through. Over my shoulder, I could see Cass and Aly trying to swim away, also pulling at the rope in vain.

It was like a tug of war between two dimensions.

Marco swam next to me and grabbed onto the rope. Fumbling in his pack, he took out a pocket knife. He slashed once … twice …

The rope snaked outward. It snapped back into the portal.

We tumbled backward. The portal glowed, but its center was pitch black. The frayed ends of the rope disappeared into the darkness.

Where was Torquin? Marco began swimming toward the portal with one arm, waving us up toward the surface with the other. My concern for Torquin’s life lost out to sheer panic. I didn’t have long before my breath would run out. None of us did.

I turned and kicked hard. Aly was pumping toward the surface. I grabbed onto Cass’s length of rope and held tight, pulling him along.

Cass and I exploded through the surface, gasping and coughing. I looked around desperately, expecting to crash into a boulder. But the river was calmer than the last time. “Where’s … Aly … Marco?” Cass gulped.

A shock of dyed red hair burst through to the sunlight. Aly looked like she could barely breathe. She was sinking under. I had to help. “Can you make it to the river bank on your own?” I asked Cass.

“No!” he said.

“Yeeeeahhhhh!” cried a voice closer to the shore. Marco was thrusting upward, shaking his head, blinking his eyes. In a nanosecond, he was swimming toward Aly. “Go to shore!” he cried out to us. “Did Torquin come through?”

“I don’t think so!” I said.

With powerful strokes, Marco swam Aly to the shallows, where she was able to stand. Then he plunged back the way he’d come. “We have to find him!” he cried out. “I’ll be right back!”

As he disappeared under the surface, Cass and I swam toward Aly. We were in a different part of the river from last time. Shallower. It didn’t hurt that the bad weather had stopped, and the current was calmer.

We reached the sandy soil and flopped next to Aly, exhausted. “Next time …” she panted, “we bring … water wings.”

Gasping for breath, we waited, staring at the river for Marco. Just as I was contemplating a jump back in to find him, his head broke through. We stood eagerly as he swam to shore. Trudging up to the bank, he shook his head, his lips drawn tight. “Couldn’t do it …” he said. “Went right up to the portal … tried to look through … considered going back …” In frustration, he smacked his right fist into his left palm.

“You did your best, Marco,” Aly said. “Even you need to breathe.”

“I—I failed,” Marco said. “I didn’t get him.”

He pushed his way through us and slumped down onto the sandy soil. Cass sat next to him, putting a skinny arm around his broad shoulder. “I know how you feel, brother Marco,” he said.

“Maybe Torquin got stuck in the portal,” Aly suggested.

Marco shook his head. “We could fit an ox team through that thing.”

“He might have gotten cold feet at the last minute,” Cass said, “and gone back.”

We all nodded, but frankly that didn’t sound like Torquin. Fear wasn’t in his toolkit. He was a good swimmer. And he had lungs the size of a truck engine. All I could think about were Professor Bhegad’s words: What rules do apply, in a world that one must experience cross-dimensionally?

“Maybe he couldn’t get through,” I said quietly. “Maybe we’re the only ones who can. I mean, let’s face it, we each do have something he doesn’t have.”

“A vocabulary of more than fifty words?” Cass said with a wan smile. Under the circumstances, his joke landed flat.

“The gene,” I said. “G7W. He’s not a Select.”

“You think the portal recognizes a gene?” Aly asked.

“Think of the weird things that have happened to us,” I said. “The waterfall that healed Marco’s body. The Heptakiklos that called to me. The fact that I could pull out a shard and let a griffin through, when others had tried but couldn’t. All these things happened near a flux area, too. The gene gives us special abilities. Maybe jumping through the portal is one of them.”

Cass nodded. “So while we passed through, Torquin just … hit a wall. Which means he may be back with Professor Bhegad, safe and sound.”

“Right,” I said.

“Right,” Aly agreed.

We all stared silently at the gently rolling Euphrates, wanting to believe what we’d just agreed on. Hoping our beefy, laconic guardian was all right. Knowing in our hearts and minds that no matter his outcome, one thing was clear.

We were on our own.

Cass was crouched low, stroking a palm-sized green lizard in his hand. “Hey, look! It’s not afraid of me!”

Aly crouched beside him. “She’s cute. She can be our mascot. Let’s call her Lucy.”

Cass cocked his head. “Leonard. I’m getting more of a he-vibe.”

“Uh, dudes?” Marco looked exasperated. “I’m getting a go-vibe. Come on.”

Cass gently put Leonard in his backpack. We continued walking toward the city, hidden by the trees. It was the height of the day and the sun beat mercilessly. Through the branches I glanced at the farm. Carts rested on the side of yellow mud-brick buildings. I figured the farmers must have been napping.

Cass sniffed the air. “Barley. That’s what they’re growing.”

“How do you know?” Marco asked. “Were you raised on a farm?”

“No.” Cass’s face clouded. “Well, sort of. I lived on one for a couple of years. An aunt and uncle. Didn’t work out too well.”

“Sorry to hear it,” Marco said.

Cass nodded. “No worries. Really.”

As they walked on ahead, I glanced at Aly. Questioning Cass about his childhood was never a good idea. “I’m worried about Cass,” she confided, lowering her voice. “He thinks his powers are dwindling. And he’s so sensitive about everything. Especially his past.”

“At least he’s got us. We’re his family now,” I said. “That should give him strength.”

Aly let out a little snort. “That’s a scary thought. Four kids who might not live to see fourteen. We’re about as dysfunctional as it gets.”

Ahead of us, Marco had put an arm around Cass’s shoulder. He was telling some story, making Cass laugh. “Look,” I said, gesturing with my chin. “Dysfunctional, maybe, but don’t they look like a big brother and little brother?”

Aly’s worried expression turned into a smile. “Yeah.”

As we neared the edge of the pine grove, we were all dripping sweat. Cass and Marco had pulled ahead, and they were now crouched by a pine tree at the edge of the grove. We gathered next to them. No one had noticed us. No one was near. So we could take in a long, clear view of the city.

Babylon sprawled out from both sides of the river. Its wall was surrounded by a moat, channeled from the river itself. A great arched gate, leading into a tunnel, breached the wall far to our left. Outside that gate, a crowd had gathered at the moat’s edge. They were almost all men. Their tunics had more folds than ours, with thicker material bordered in a bright color.

“We didn’t get the garb right,” Aly said.

“We look like the poor relatives,” Cass remarked.

“It is what it is,” Marco said. “Let’s walk like we belong.”

As we stepped out from the trees, I noticed that Cass was chewing gum. “Spit that out!” I said. “You weren’t supposed to bring stuff like that.”

“But it’s just gum,” Cass protested.

“Hasn’t been invented yet,” Aly said. “We don’t want to look unusual.”

Cass reluctantly spat a huge wad of gum into the bushes. “In two thousand years, some archaeologist is going to find that and decide that the Babylonians invented gum,” he muttered. “You making me spit that out may have changed the future.”

We all followed Marco out of the trees and onto the desert soil. As we approached the city wall, the crowd grew loud and raucous. They’d formed a semicircle with their backs to us, shouting and laughing. Some of them scooped rocks off the ground. Three men stood guard, facing outward, looking blankly off in to the distance. They wore brocaded tunics with bronze breastplates and feathered helmets. They looked powerful and bored.

“Behold Babylon,” Marco whispered.