Полная версия

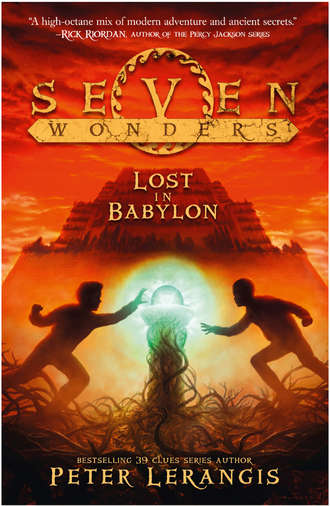

Lost in Babylon

As I passed through the hole, it let out a deep, threatening buzz. A halo of green-white light shot sparks from its circumference into my body. My mouth opened into an involuntary scream. I collided with Marco and Cass, but they felt porous, as if our molecules were joining, passing through one another. My left leg smacked against something hard, and I bounced away.

I was spinning with impossible speed, as if my head were in ten places at once. And then I felt myself catapulted forward, and I thought my limbs would separate into different directions.

But they didn’t. I flattened out, decelerating. The water’s temperature abruptly dropped, and so did its texture. All at once it had become clear and cool—and I was whole again. Solid. But the change had unsettled every biological function inside me. My brain registered relief, but my lungs were in chaos. As if someone had reached inside and squeezed them with a steel fist.

Aly … Marco … Cass. I spotted them all in my peripheral vision, rising. But Cass’s legs hung like tentacles, undulating with each of Marco’s powerful thrusts. Those two would reach the surface first. I pushed with all remaining strength, fighting to stay conscious. Aiming toward a dull, flat-gray surface glow above us.

My arms slowed … then stopped.

I felt myself traveling to a dream world of bright sun and cool breezes. I was floating over a field of waving grass, where a white-robed shape stood from a circle embedded in the ground.

As she turned, I could see the seven Loculi, glowing, revolving. They seemed to blend together, so their shapes merged into a kind of circular cloud.

The Dream.

No. I don’t want it now. Because I’m not asleep. Because if I have the Dream now, it might be because I’m dead.

“I knew you would come.”

The voice was unfamiliar, yet I felt it was a part of me. I knew instantly who the figure was. She turned slowly. Her eyes were the color of a clear tropical ocean, her face gentle and kind, ringed with a floating mane of glorious red hair.

Her name was Qalani.

Whenever I’d seen her, it had been in a ring of explosions, some kind of strange flashback to the destruction of Atlantis. In the Dream, I came close to death but always woke up.

Here, she had come to meet me. As always, her face looked familiar. She resembled my mom, Anne McKinley—and now, deep under the Euphrates, it was more than a resemblance. It was a beckoning, a welcoming.

“Hi, Mom,” I said.

“I’ve been waiting,” she said with a knowing smile. “Welcome to have you back.”

I couldn’t help grinning. Our old family saying! I’d blurted it out to Dad once, when he returned from a business trip to Manila. From then on, we always used it as our own private joke.

I felt strangely peaceful as she reached toward me. I would be fine. I would finally be meeting her, in a better place.

Her hand gripped my shoulder, and darkness quickly closed in.

She was gone.

“Mo-o-om!” I shouted.

“No! Marco!” a voice shouted back.

I blinked water from my eyes. I could see Marco rising and falling on a wild current. He let go of me, swimming toward Aly, pushing her toward the bank. I could see her struggling to stand, grabbing onto Cass’s arm.

I was too far into the middle, the deeper water. I struggled to push myself high enough above the surface for a proper breath. As I went under again, I fought to stay conscious.

“Hang on, brother!” Marco shouted.

His fingers locked around my arm. He was swimming beside me, pulling us both toward the bank. His arms dug hard into the frothing current. Aly and Cass were struggling onto the shore, staring over their shoulders at me in horror.

Marco and I bounced downstream in a helpless zigzag. We careened around a jutting rock that rose up between us, forcing Marco to let go of me. Directly in our path was a downed tree. I kicked hard and up, opened my arms, and let it hit me full force in the chest. My legs swept under the wood as I held tight.

“Marco!” I yelled.

“Here!” Marco clung to the tree about three feet to my left, closer to the riverbank. We both hung there, catching our breaths. “How’s your grip, Brother Jack? Steady?”

I nodded. “I think … I can make my way to the shore!”

“Good—see you there!” Marco swung up onto the wood, stood carefully, and scampered toward the shore like an Olympic gymnast. Jumping onto the bank, he began calling for Aly and Cass.

I yanked myself onto the fallen tree. Lying there, I felt my chest beating against the slippery wood. I didn’t dare try to stand. Slowly I reached out toward the shore, gripping farther along the branch. In this way I managed to shimmy along at a snail’s pace until I finally reached the bank and flopped onto the mud.

Farther upstream, Aly had made it to solid ground. Marco was back in the river, helping Cass out of the water. I struggled to my feet. My legs ached and rain pelted my face, but I hobbled toward them as fast as I could in the soggy soil.

A total freak rainstorm. One moment, hot and dry air. The next, this. Was this normal in the desert?

What was going on here?

“Jack!” Aly threw her arms around me as I arrived. Her face was warm against my neck. I think she was crying.

“Behave, you two,” Marco said.

I pulled away, feeling the blood rush to my face. “What just happened?” I said.

Cass was staring across the river, looked dazed. “Okay, we jumped into the river. We hit a rough patch. We came out the other end. So … we should be staring across the river, at the place we left from, right?”

“Left,” Marco said. “Right.”

“So where is everything?” he asked. “Where are Torquin, Bhegad, Nirvana? They should have made it down here by now.”

Aly and I followed Cass’s glance. “Looks like we were carried pretty far downstream,” I said.

“Yeah, like a zillion miles away,” I said.

“That,” Cass said, “would be geographically elbissopmi.”

“How do you do that?” Aly said.

A dense cloud cover made it hard to see north and south, but I could see no sign of human life—no settlements, no Babylonian ruins, no KI people. Just swollen river in either direction.

“We can’t waste time—come on!” Marco was already heading up the slope into a thick pine grove.

Cass, Aly, and I shared a wary glance. “Marco, you’re not telling us something,” I said. “What just happened?”

Marco scampered through the trees without an answer, as if our near drowning, our battering against the rocks, had never happened. Cass looked at him in disbelief. “He can’t be serious.”

“Chill is not in that boy’s vocabulary,” Aly said.

We followed behind as fast as we could. My legs were bruised and my head bloody. My arms felt as if I’d been bench-pressing a rhinoceros. The slope wasn’t too steep, really, but in our condition it felt like Mount Everest. We caught up with Marco at the edge of the pine trees. Here, everything seemed a little more familiar. Just beyond the grove I could see a vast plain of dirt to the horizon. The clouds were lifting, the water-soaked ground quickly drying. Scrubby bushes dotted the landscape, which was crisscrossed by a network of wide paths cut through the plain.

“Check it out,” Marco said, gesturing to the left.

A giant rainbow arched through the sky, sloping downward into a city of low, square, yellow-brown buildings—thousands of them, most with crown-like sandcastle roofs. The city rose on a gentle hill, and if I wasn’t mistaken, I thought I could see another wall deeper inside the city. The outer wall contained a mammoth arched gate of cobalt-blue tiles. In the center of the city was a towering building shaped like a layer cake. Its sides were ornately carved, its windows spiraling up to a tapered peak. The city’s outer wall was surrounded by a moat, which seemed to draw water from the Euphrates. Closer to us, outside the city limits, were farms where oxen trudged slowly, plowing the fields.

“Either I’m dreaming,” Aly said, “or no one ever told us there was a phenomenally accurate ancient Babylonian theme park on the other side of the river.”

“I don’t remember seeing this from the air,” I said, turning to Cass. “How about you, Mr. GPS—any ideas?”

Cass shook his head, baffled. “Sorry. Clueless.”

“It’s not a theme park,” Marco said, ducking back into the trees. “And it’s not the other side of the river. Follow me, and keep yourselves hidden by the trees as long as possible.”

“Marco,” Aly said, “what do you know that you’re not telling us?”

“Trust me,” Marco said. “To quote Alfred Einstein: ‘a follower tells, but a leader shows.’”

He slipped back into the trees, heading in the direction of the city. Aly, Cass, and I fell in behind him. “It’s Albert Einstein,” Aly corrected him. “And I don’t believe he ever said that.”

“Maybe it was George Washington,” Marco said.

We trudged through the brush. The river roared to our right. Roared? Okay, it was swollen by the rain—but how long could it have rained, five minutes?

The tree cover seemed a lot denser than I’d remembered seeing it from the other side. It partially obscured our view of the city, save for a few glimpses of distant yellowish walls.

As the rain clouds burned away, the temperature climbed. We may have walked for ten minutes or an hour, but it felt like ten days. My body still felt creaky from our little swim adventure. All I wanted to do was lie down. I could tell Cass and Aly were hurting, too. Only Marco still seemed fresh and dewy. “How far are we going?” I called ahead.

“Ask George Washington,” Aly mumbled.

Marco took a sharp turn and stopped short at the edge of the trees. He peered around a trunk, signaling us to come close. With a flourish, he gestured to his left. “Abracadabra, dudes.”

I looked toward the city and felt my jaw drop. The tree cover completely ended here. Up close, I could see that the city spilled directly to the banks of the Euphrates.

Marco was climbing a pine tree and urged us to do the same. The branches hadn’t been trimmed, so it was easy to get maybe fifteen feet or so above the ground.

From this vantage point we could see over the outer wall and into the city. It was no theme park. Way too vast for that. It wasn’t a city, either. Not like the ones I knew—no power wires, no cell towers, no cars. The roads leading into the city were hard-packed dirt. On one of them trudged a group of bearded men in white robes and sandals, leading swaybacked mules laden with canvas bags. They were heading toward a bridge that led over the moat and into the city gate. From the lookout towers, guards watched them approach. I craned my neck to see what the place was like inside, but the walls were too high.

“These people are about as low-tech as it gets,” Cass said. “Like, from another century.”

I felt a chill in spite of the hot sun. “From another millennium,” I added.

“M-M-Marco …?” Aly said. “You have some ’splainin’ to do.”

Marco shook his head in wonder. “Okay. I’m as baffled as you are. Lost in the Land of the Big Duh. No idea where we are or how we got here. I wanted to show you, partly because I couldn’t believe it was real. But you see it, right? I’m not crazy, am I? Because I was having my doubts.”

A rhythmic whacking noise nearly made me slip off my branch. We all scrambled down the trees. A little kid’s voice was coming nearer, singing in some strange language. Instinctively we drew closer together.

Strolling up the path toward us was a dark-haired boy of about six, wearing a plain brown toga and holding a gnarled stick. As he sang, he whacked a hollow, dead tree in rhythm, his eyes wandering idly.

He stopped cold when he saw us.

“Keep singing, little dude,” Marco said. “I like that. Kind of a reggae thing.”

The boy glanced from our faces to our clothes. He dropped his stick and darted back toward the main road. We must have seemed pretty strange to him, because he began shouting anxiously in a language none of us knew.

At the road, a caravan of camels turned lazily toward him. A man with graying hair was at the head of the caravan, leaning on a stick and talking to a city guard dressed in leather armor, who had strolled out to meet him. Both of them turned toward us.

The guard had a thick black beard and shoulders the size of a bull. Narrowing his eyes, he began walking our way, a spear balanced in his hand. He shouted to us with odd, guttural words.

“What’s he saying?” Aly asked.

“‘Does this toga make me look fat?’ How should I know?” Cass said.

“We’re not in Kansas anymore, Fido,” Marco said. “I say we book it.”

He pushed us toward the river. We began running into the woods, down the slope, tripping over bushes and roots. I felt like I was re-banging every bruise I had. Marco was the first to reach the river banks. Cass was close behind, looking fearfully over his shoulder.

“He’ll give up,” Marco whispered. “He has no reason to be mad at us, just probably thinks we’re dressed weird. We hide for a few minutes and wait for Spartacus and Camel Guy to go away. Then when things are quieter, we go find the Hanging Gardens.”

“Um, by the way, it’s Toto,” Aly whispered.

“What?” Marco snapped.

“We’re not in Kansas anymore, Toto,” Aly said. “Not Fido. It’s a line from The Wizard of Oz.”

As we crouched behind some bushes, Marco’s eyes grew wide. I looked in the direction of his glance. Over the tops of the trees, a solid black band shimmered across the sky. It wasn’t a cloud cover exactly, but more like a distant gigantic cape.

“And, um … that thing?” Marco said. “That’s maybe the wizard’s curtain?”

I stood and ran to higher ground, to a place where I could see the city. I spotted the guard again and ducked behind a tree. But he wasn’t concerned about us anymore. The guard, the camel driver, the boy, and a couple of other men were hurriedly herding the camels toward the bridge.

“I don’t like this,” Cass said as he caught up to where I was standing. “Let’s get out of here before a tornado strikes. We need to get Professor Bhegad. He’ll know what to do.”

“No way, bro,” Marco protested. “It’s just weather. We need to move forward. And I have about a million things I have to tell you.”

In the distance an animal roared. Birds flew frantically overhead, and a series of crazy, high-pitched screeches pierced the air. This place was giving me the creeps. “Tell us on the other side,” I said, heading back down.

Aly, Cass, and I bolted for the river. It was three against one.

“Wusses. All of you,” Marco said. And with a disgusted sigh, he followed us back in to the river.

It was Aly’s voice. That much I knew. And I had a vague idea why she was sounding so dorky.

I tried to open my eyes but the sun was searing hot. My muscles ached and my clothes were still wet. I blinked and forced myself to squint upward. Marco, Aly, and Cass were leaning over me, panting and wet. Behind them, the cliff rose into the harsh, unforgiving sun.

“Don’t tell me,” I said. “It’s a line from a movie.”

Aly beamed. “Sorry. I can’t help it. I’m so relieved. The original Frankenstein. Colin Clive.”

“Welcome to the living,” Marco said, helping me up off the sand. “The original Seven Wonders Story. Marco Ramsay.”

The landscape whirled as I struggled upward. I looked warily up the slope. “What happened to Ali Baba and the camels?”

“Gone,” Marco replied, his eyes dancing with excitement. “We are back to the same spot where we left in the first place. And are you noticing something else? Look around. Look closely.”

I saw the worn path to the top of the ridge. I saw the gray river, placid under the rising sun. “Wait,” I said. “When we left, the sun was almost over our heads. Now it’s lower.”

“Bingo!” Marco said.

“From Bingo,” Cass murmured. “Starring Bingo.”

“Meaning what, Marco?” Aly said. “I’m supposed to be the smart one. What do you understand that I don’t?”

“Hey!” A distant, high-pitched voice made us all turn sharply. Nirvana was sprinting up the beach in loud Hawaiian shorts, a KISS T-shirt, and aviator sunglasses. “Oh … my … Gandalf!” she screamed. “Where have you guys been?”

Marco spun around. “Underwater. ’Sup, Dawg? Where’s Bhegad?”

Nirvana slapped him in the face, hard.

“Ow,” Marco said. “Happy to see you, too.”

“We thought you were dead!” Nirvana replied. “After you jumped? I nearly had a heart attack! Bhegad and Fiddle and the Hulk—they’re all in each other’s faces. ‘How could you let this happen?’ ‘How could you?’ ‘How could you?’ Blah blah blah. Fiddle’s insisting we call nine-one-one, Bhegad says we can’t, Torquin’s just going postal, and I’m Will you guys just take a pill? So we all jump in the river to look for you, except for Bhegad, who’s so mad he’s practically doing wheelies. Finally we give up. All we can do is wait. Soon we assume you all drowned. Torquin is crying. Yes, tears from a stone. It does happen. Fiddle is like, ‘Time to break up the KI and look for a new job!’ Bhegad insists we set up camp. Maybe you’ll come back. Or we’ll find the bodies. So we’ve been sitting here for two days eating beef jerky and—”

“Wait,” I said, sitting up. “Two days?”

“Torquin was crying?” Cass said.

Over Nirvana’s shoulder, I could see Fiddle pushing Professor Bhegad toward us. Torquin was waddling along beside them, his beefy face twisted into a pained expression that looked like indigestion but probably was concern. About twenty feet behind them was a camp-type setup—three big tents, a grill, and a few boxes of supplies.

When had they set that up?

“By the Great Qalani!” the old man cried, holding his arms wide. “You’re—okay!”

No one of us knew quite what to do. Professor Bhegad wasn’t exactly a huggy kind of guy. So I stuck out my hand. He shook it so hard I thought my fingers would fall off. “What happened?” he asked, his eyes darting toward Marco. “If I weren’t so relieved, I’d be furious!”

Marco’s face was flushed. He blinked his eyes. “My bad, P. Beg … shouldn’t have run off like that … whoa … spins … mind if I sit? I think I swallowed too much river water.”

“Torquin, bring him to the tent. Now!” Bhegad snapped. “Summon every doctor we have.”

Marco frowned, drawing himself up to full height with a cocky smile. “Hey, don’t get your knickers in a twist, P. Beg. I’m good.”

But he didn’t look good. His color was way off. I glanced at Aly, but she was intent on her watch. “Um, guys? What time is it? And what day?”

Fiddle gave her a curious look, then checked his watch. “Ten-forty-two A.M. Saturday.”

“My watch says six thirty-nine, Thursday,” Aly said.

“We fix,” Torquin said. “Busted watches a KI specialty.”

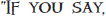

“It’s still working, and it’s waterproof,” Aly said. “Look, the second hand is moving. We left at 6:02, our time here in Iraq, and we were back by 6:29. Exactly twenty-seven minutes by my watch. But here—actually in this place—almost two days passed for you!”

“One day and sixteen hours, and forty minutes,” Cass said. “Well, maybe sixteen and a half, if you count discussion time before we actually dove.”

“Aly, this does not make sense,” I said.

“And anything else about this adventure does?” Aly’s face was pale, her eyes focused on Professor Bhegad.

But the professor was rolling forward, intent on Marco. “Did no one hear me?” he said. “Bring that child to the tent, Torquin—now!”

Marco waved Torquin away. But he was staggering backward. His smile abruptly dropped.

And then, so did his body.

As we watched in horror, Marco thumped to the sand, writhing in agony.

His eyes flickered. Professor Bhegad exhaled with relief. Behind him, Fiddle let out a whoop of joy. “You are a strong boy,” Bhegad said. “I wasn’t sure the treatment would take.”

“I didn’t think I needed treatments,” Marco replied. A rueful smile creased his face as he looked up at Aly, Cass, and me. “So much for Marco the Immortal.”

Cass leaned down and gave him a hug. “Brother M, we like you just the way you are.”

“Sounds like a song,” said Nirvana, who was clutching Fiddle’s and Torquin’s arms.

I glanced at Aly and noticed she was tearing up. I sidled close to her. I kind of wanted to put my arm around her, but I wasn’t sure if that would be too weird. She gave me a look, frowned, and angled away. “My eyes …” she said. “Must have gotten some sand in them …”

“Aly was telling me about your adventure,” Bhegad said to Marco. “The Loculus seeming to call from the river … the weather change … the city on the other side. It sounds like one of your dreams.”

“Dreams don’t change the passage of time, Professor Bhegad,” Aly said.

“It was real, dude,” Marco said. “Like some overgrown Disney set. This big old city with dirt roads and no cars and people dressed in togas, and some big old pointy buildings.”

Fiddle nodded. “Hm. Ziggurats …”

“Nope,” Marco said. “No smoking.”

“Not cigarettes, ziggurats—tiered structures, places of worship.” Bhegad scratched his head, suddenly deep in thought. “And the rest of you—you all confirm Marco’s observation?”

Nirvana threw up her arms. “When Aly talks about it, you assume it’s a dream. But when Marco says it, you take it seriously. A little gender bias, maybe?”

“My apologies, old habits learned at Yale,” Bhegad said. “I take all of you seriously. Even though you do seem to be talking about a trip into the past—which couldn’t be, pardon the expression, anything more than a fairy tale.”

“So let’s apply some science.” Aly sank to the ground and began making calculations in the sand with her finger. “Okay. Twenty-seven minutes there, about a day and sixteen-and-a-half hours here. That’s this many hours …”

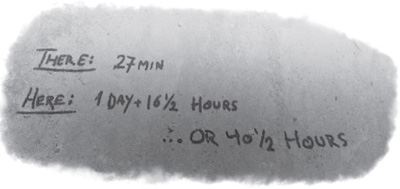

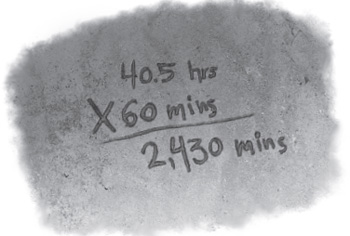

“Twenty-seven minutes there equals forty-and-a-half hours here?” I asked.

“How many minutes would that be?” she said. “Sixty minutes in an hour, so multiply by sixty …”

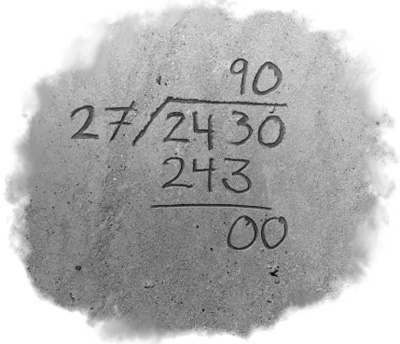

Aly’s fingers were flying. “So twenty-seven minutes passed while we were there. But twenty-four-hundred thirty minutes passed here. What’s the ratio?”

“Ninety!” Aly’s eyes were blazing. “It means we went to a place where time travels ninety times slower than it does here.”