Полная версия

Picture Perfect

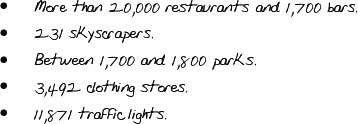

“OOOH!” Nat shouts at the top of her voice. “You can see where Calvin Klein was born and Leo DiCaprio lives!”

“You can visit the Museum of Math in Brooklyn.”

“You can stand outside shop windows wearing lots of costume jewellery and eat pastries,” Nat sighs, her eyes lit up. “You can see celebrities buying sandwiches every day.”

“Hopefully,” Toby adds, “you will not be one of the 419 murders that happen per 100,000 people in the city. Statistically, the odds are in your favour.”

I blink.

If I’d known the impact of me leaving the country would be so slight, I’d have started training to be an astronaut some time ago.

“I’m glad you’re both so delighted.”

“Harriet,” Nat laughs, putting an arm round me. “Six months is nothing. Although it does suck that you’re going before your birthday – maybe you can have second-round celebrations when you get back, like Kate Moss or the Queen. And you’ll be having so much fun it will just whizz past.”

“It’s only 184 days,” Toby agrees, nodding enthusiastically. “4,416 hours. 264,960 minutes. I can invest the time wisely and think up a really excellent plan for when you get back.”

As mature and supportive as they’re being, I can’t help wishing I was having a shoe thrown at my head. Or an eyeshadow compact.

At least then I’d know they’d miss me.

“Exactly,” I say in my fakest, sunniest voice. “It’s all very exciting. Anyway, I’ve got some packing to do and …”

My phone starts ringing.

Oh, thank goodness. My parents have finally got their interruptive timing spot on.

“Oops,” I say loudly as I grab my phone out of my pocket. “I should probably take this outs—”

There are five million hairs all over the human body, and suddenly every single one of mine is standing on end.

Because it’s not my parents.

It’s Nick.

July 8th

“Are you sure?” I said doubtfully. “I’m not really on the list.”

Nick laughed.

“You’re on my list,” he said, putting his arm around me. “Admittedly it’s a really short one and for the next few hours your name is –” he looked at the silver ticket in his hands – “Isobel Marigolden.”

I stared at the enormous warehouse.

It looked like it was still under construction. There were dark grey bars lining the ceiling, and blotches of white paint on the floor. Dirty plastic sheets were hanging in grimly lit sections at the back. Down the middle was a wide, shabbily painted silver strip and hard metal seats neatly lined the two longest sides of the room.

I sat down nervously.

“Can I come backstage with you?” I asked. “Maybe I can help you get ready.”

Nick gently picked me up and moved me three seats along and two rows back.

“You can’t just sit where you like at a Prada fashion show, Harriet,” he laughed. “And backstage there are going to be thirty boys in dirty underpants and mismatched socks. I’m not entirely sure you’d want to see that, even if the designer allowed it.”

The boy’s PE changing room at school sounded eerily similar. “Good point.”

“So can you wait here?”

“I have this,” I said, waving Anna Karenina. “I can probably sit for three whole days happily.”

“If you look for perfection, you’ll never be content,” Nick said in a bizarre voice.

My eyes widened. “OK, a) you’ve read Anna Karenina? and b) that was possibly the single worst attempt at a British accent I’ve ever heard.”

“That’s because it was Russian,” Nick said, raising an eyebrow. “And yes, I’ve read it. Or, you know: looked at the pictures really hard. I am a model, after all.”

He smiled and leant down to kiss my nose.

“I’ll wait,” I said, flushing and opening the book, which I suddenly liked a billion times more because it now had Nick in every single line.

“Thank you.” My boyfriend gave me another quick kiss on the lips. “I’ll see you later, my little geek.”

Over the next two hours, the room filled with people; slowly at first, and then in great, noisy swarms.

People in shiny black, people in red lace, people in white shirts with pointy collars. People who knew exactly where they were supposed to sit and were doing it without complaining about the hardness of the seats.

Then the room got very quiet and very dark. Music started pumping and lights started flashing. The dirty plastic sheets parted.

And out walked the boys, one by one.

They slunk to the front of the room, stopped, stared, turned and slunk back out again like prowling, pointy-hipped wolves. Dozens of them: angular and floppy-haired and stern. In sharp silver shirts and grey suits; black jackets and blue ties.

As the music vibrated, I could feel my stomach clenching.

I miss this, I suddenly realised.

I missed the music I didn’t recognise and the bright lights and the dark audience. I missed the bustle and panic and noise in a room somewhere behind us. I missed the excitement and the bright eyes and the rustle of papers as people made notes.

I missed Wilbur and his ridiculous outfits and his made-up language. I missed Rin and Kylie Minogue, the sock-wearing cat who hated going for walks. I missed Tokyo and being transformed by stylists. I even slightly missed the terrifying Yuka Ito.

But most of all I missed Nick.

Suddenly, the plastic sheets parted and out walked another boy. A dark-haired, olive-skinned boy in a sharp black jacket with a bright silver collar. His face was set, his dark eyes were narrowed, his mouth was clenched. He strode towards us with firm, straight steps: purposeful. Furious.

I blinked as this angry, tense stranger pounded down the catwalk. There wasn’t a single twinkle or slouch. Not a jot of laughter or crinkle around his eyes.

Two hundred people watched keenly as my boyfriend got to the end of the catwalk, stopped and posed.

The blue whale has a heart big enough for a human to crawl through its ventricles. For just a few seconds, my heart felt so big, a blue whale could have swum through mine.

I waited for Nick to turn towards me. To notice me in the crowd.

Finally, just before he started back towards the curtains, he looked straight at me.

He winked.

And – just like that – I had my Lion Boy back.

Seriously.

If it had been on fire, I doubt I could have moved faster.

“Nick?” I say breathlessly as soon as I’ve shut the front door. “Nick? Are you there?”

Then I try to rephrase it so I sound a bit less desperate. “I mean, hi, whatever, how are you?”

“Hey,” he laughs warmly. “And whatever to you too.”

Apparently butterflies need an ideal body temperature of between eighty-five and one hundred degrees to fly. I must be exactly the right habitat, because my entire body is suddenly full of them. Red ones, blue ones, green ones, white ones. Fluttering like a rainbow inside me.

Then I remember the silence over the last few days.

“How’s Africa?” I say, and the butterflies suddenly go very still.

“Harriet, I’m so sorry. I’ve been out in the desert on a shoot, and there was zero reception. I even got the photographer to drive me to the nearest village, and there was still nothing. How did you do? I want to know everything.”

A wave of relief hits me so strongly that I have to temporarily lean against a statue that Nat’s mum thinks is Andromeda but is actually Artemis just to get my breath back.

Roughly forty-three per cent of Africa is desert, and it hadn’t occurred to me for a single second Nick might be stuck in any of it.

“It went kind of brilliantly,” I say, giving him a brief update on my result.

“I’m so proud of you.”

I beam at the phone, and then at the sky, and then at a random passing squirrel. I’m so warm the butterflies have given up flying and have started sunbathing instead.

“So,” and this time it’s a real, genuine question, “what is Africa like?”

“Hot. Lots of weird-looking tall creatures that can’t run properly hanging around with long necks and eyelashes and horns coming out of their heads.”

“Giraffes?”

“I was aiming for ‘models’,” Nick laughs. “But yeah, there’s some of them wandering about too.”

I giggle like an idiot.

Normally this would be the point where I’d break into an array of interesting facts. For instance, did you know that giraffes have four stomachs, and their spots are like fingerprints and no two giraffes have the same pattern?

Or that their necks are too short for their heads to reach the ground so they have to drink water by squatting?

Or that they are the only animal who moves two legs on one side of the body and then two on the other to walk?

Instead I clear my throat.

“Come on then,” Nick says. He’s smiling: the words are all stretched and snug. “Hit me with it.”

“Hmm?”

“Whatever is preventing you from telling me multiple facts about giraffes right now.”

Sugar cookies.

“I’m … umm.” I cough. “I think that …”

Of course. I should be approaching my news about America from a totally different angle.

“Nick, did you know Admiral Horatio Nelson started dating Emma Hamilton in 1798, and then went away for two years to fight the Napoleonic Wars? They wrote a lot of letters, and their budding relationship wasn’t affected in the slightest and remained strong and beautiful throughout.”

“Is that so?”

“And OK, he was fatally wounded by a musket ball at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 and died before he could see her again, but that’s not really the point.” Wrap it up, Harriet. “So …”

“Harriet,” Nick says. “Are you going away to fight the Napoleonic wars?”

“No.”

“Are you at risk of getting hit by a stray musket ball fired from a French ship in suburban Hertfordshire?”

“No.”

“Are you planning on dying next to a man named Hardy and then having your body preserved in a large barrel of brandy?”

My boyfriend knows a lot more about Admiral Nelson than I thought he would. “No.”

“Then you probably don’t need to sound so worried.”

OK.

I need to pull this out all at once, before it gets all green and liquidy like the splinter in Year Two.

“I’m leaving England,” I say quickly. “My family is moving to New York for six months and I’ll be gone before you’re home but I’ll buy some pretty stationery and write you some poignant and heartbreaking letters and get novelty stamps and—”

“Harriet, that’s brilliant,” Nick interrupts. It’s a genuine, delighted brilliant.

I blink.

Right. It’s bad enough that Toby and Nat are thrilled by my departure, but my boyfriend? He’s supposed to be making impassioned speeches on the edge of bridges about the darkness of life without me. Not throwing a mini verbal celebration and cracking out the Harriet’s Finally Leaving banners.

“Fine,” I snap, “if that’s the way you feel then you can just—” Nick’s laughter stops me mid-rage.

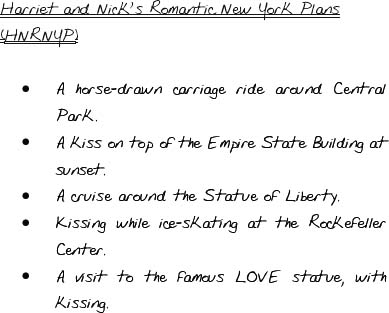

“That’s not what I meant, Harriet. New York Fashion Week starts soon, so I’m going to be there too. I get more modelling jobs in America than anywhere else. I’ll be able to see you loads. This is really brilliant news.”

I pull my phone away from my face while I get my emotions back under control.

“Harriet? You haven’t been attacked by any other kind of artillery, have you?”

“Really?” I say. “You’ll really be in New York?”

“Of course,” Nick laughs. “It’ll take a bit more than a couple of miles and an inch of water to stop me seeing you.”

I impulsively kiss my phone, even though Nick is seriously underestimating the size of the Atlantic Ocean.

“Harriet, did you just kiss your phone?”

“Umm. No. My cheek is just very … sucky.”

“Ah,” Nick laughs. “I’ve always had a weakness for girls with sucky cheeks …” There’s a shout in the background. “Shoot. I have to go. Apparently the elephant I’m riding doesn’t like my voice.”

“You rang me from the back of an elephant?”

“Yeah. I suddenly got reception and I miss you.”

“I miss you too.”

We beam at each other in silence. I don’t know how I know he’s beaming, but I just do.

“Nick,” I say, taking a deep breath. “I l—”

“Got to go. I’ll see you in New York, Freckles.”

And the phone goes dead.

And yes, there’s quite a lot of kissing, but I just quite like it, OK?

By the next morning I am desperate to leave.

In fact I’m so keen to get to New York I’ve asked my parents if I can go ahead without them.

“Do you think we’re insane?” Dad replies.

“Yes,” I tell him promptly and focus on packing with renewed enthusiasm.

Everything is ready. The house is clean. The electrics are off. The last of our belongings are being lobbed into a large van by a man who is tutting about our ‘ineffective boxing skills’.

A note has been left for Bunty saying DO NOT TRY TO DYE, BURN OR REUPHOLSTER ANYTHING. PLEASE FEED THE CAT ON A DAILY BASIS. Hugo has been sent to live temporarily with a delighted Toby while we get his American passport sorted.

And I’ve spent the evening putting together my own little box of home souvenirs to take with me. A 1,000-yen note with a picture of Mount Fuji on it. A T-shirt with a photo on the front of Rin and me riding a computer-generated unicorn. An American-English dictionary from Toby. An envelope containing a newspaper cutting of me sat with Fleur on the catwalk in Moscow, and a photo I took of Wilbur in Tokyo wearing wing-shaped sunglasses. A photo of me and Nat in cowboy hats and moustaches.

Finally, I get out a brand-new scrapbook, write

There are going to be so many things to stick in it.

Museum tickets and love letters and pressed flowers picked on our moonlit strolls in Central Park. The wrapper from a chocolate he unexpectedly pulls out of his pocket. A photo of us, playing with perspective so it looks like the Statue of Liberty is in our hands.

I’m just contentedly tucking the toy lion he bought me into the corner when my phone beeps.

H, I can’t make it to the airport! I forgot we have initiation day at college. I’M SO SORRY. Skype me when you get there! Love you so much. Nat xxx

I look blankly at the message, then text back:

No probs! Goodbyes are rubbish anyway, aren’t they? Speak soon! Love you too! H xxx

“Ready?” Annabel says as I pop my little shoebox of memories into my backpack, zip it all up and sling it over my shoulders.

“Ready,” I say quietly.

America, here I come.

I have a lot of things to do.

Documentaries about turbulence to watch, crosswords to complete, key landmarks to look for out of the window, a long and confusing list of American spellings to learn.

Unfortunately, Tabitha has other plans.

I’d never realised she liked England so much, but she’s obviously quite attached. As soon as the air steward starts showing us the emergency exits, she starts yelling and doesn’t draw breath for the rest of the journey.

Apparently women in Ancient Greece made blusher from a mixture of crushed mulberries and strawberries. By the time we land, seven hours later, Annabel is so flushed it looks like she’s made a bath of it and jumped straight in.

“Tabitha,” she says firmly as we collect our bags from the overhead lockers. She wipes her forehead with her jumper sleeve. “I love you more than life itself, but if you scream again like that on public transport I will leave you in the hold, OK?”

Tabby blinks at her with wide eyes, hissy-fit over.

“Don’t give me that look, missy,” Annabel sighs. “I’ve had eleven years of practice with your father.”

Dad leans over Tabitha. “She’s nailing it,” he says approvingly, tickling her tummy. “That’s my girl. Work that twinkle.”

My sister squeaks and kicks her little legs like a frog attempting the high jump. An air steward stops by us in the aisle.

“Oh ma Gahd,” she says, putting a hand on her chest. “Your baby is the cutest. Isn’t she just adorable? I could eat her up.”

We look at Tabitha with narrow, exhausted eyes.

Dad put her in a Union Jack onesie especially for the journey. Her red hair is all curly and fluffy, her cheeks are all pink, the toy rabbit I bought her is propped on her shoulder and she’s blowing enthusiastic bubbles like a tiny goldfish.

Tabby does, indeed, look adorable.

They were obviously working in a different part of the plane twenty minutes ago. There was an entirely different word for her then.

“Please go for it,” Annabel says drily. “She goes well with ketchup and a bit of oregano.”

The air steward’s eyes get very round. “Ha,” she says awkwardly. “Hahaha. You Brits are hilarious.”

And then she hurries away as fast as possible.

This is it, I realise as we push ourselves through the enormous, shiny JFK airport.

It’s like we’ve just hit the restart button.

It feels like London, except bigger. Glossier. Cleaner. The floors are sparkly and everything is ordered and in neat lines. There’s a twang in the air, and the biggest American flag I have seen in my life is hanging from the ceiling.

We all stand and stare at it in silence.

“Well,” Annabel says finally, “at least we don’t need to check that we’re in the right country.”

“Unless it’s a trick,” Dad shrugs. “That would be pretty funny, right? Welcome to Australia! Hahaha GOTCHA!”

“You have a nice day, now!” a lady in an airport outfit says chirpily as she walks past.

“You too!” Dad shouts after her. “Thank you so much! How extremely thoughtful of you! Do you have anything fun planned?”

She looks in alarm at the airport security.

Well: safe-ish, anyway.

Dad signs a few bits of paper and then leads us in excitement outside into an enormous car park and towards a large silver car. It’s so enormous it makes our car at home look like something a toy drives.

“A Dodge Durango?” Dad says. “They sent me a Dodge Durango?” He starts running his hands along it. “Front engine, rear-wheel drive. Harriet, this is built on the same platform as a Jeep Grand Cherokee!”

This is possibly the only fact in the world I’ve ever heard that I’m not even vaguely interested in.

“Are we prepared for an adventure?” Annabel says, popping Tabitha into the car seat and winking at me.

“Of course,” I say with a deep breath.

And we start the drive into the bright lights of the Big Apple.

I don’t want to be rude, but frankly you’d think they’d be a bit more noticeable.

Fifty minutes into the journey I still can’t see any of them. I’ve got my nose pressed against the window and three guidebooks on my lap, but the roads are getting wider and the buildings are getting smaller and the people fewer, rather than the other way round.

There’s a dodgy-looking restaurant on the side of the road, and an enormous superstore with flashing lights on the other. There are some of the biggest trucks I have ever seen in my life, blowing their horns at each other.

So far, skyscrapers spotted: 0.

Parks: 0.

Little ladies with push-along shopping trolleys: 6.

The Empire State Building is 381 metres high. It really shouldn’t be this difficult to see.

Another twenty minutes pass, and then another thirty, and I’m finally starting to lose my brand-new shiny patience. I know I’m supposed to be acting like an adult now, but clearly my parents don’t know how to navigate America.

“Are we lost?” I say helpfully, leaning forward and sticking my head in between the seats. “Because if you need help reading a map, I have a Brownie badge that will confirm I’m quite good at it.”

Silence.

I look back at the guidebook. “I think we should have gone over the Hudson River by now. Are you sure we’re going in the right direction?”

Then I see my parents glance at each other.

“What’s going on?” I say as the car starts pulling into a tiny little road surrounded by small, solitary houses made out of white, blue or grey slats and shutters around the windows and pointy roofs. There’s a dog sitting on the porch, casually licking itself, and a ginger cat perched on the fence opposite, staring at it in total disgust.

One of the curtains twitches, and a small boy on a bike rides slowly past. Another silver SUV drives by with a family inside it.

At random intervals on this road there is a tiny hairdresser’s called CURL UP AND DYE, a small mechanical shop called JONNO’S AUTOPARTS and somewhere that sells chicken called MANDYS.

On the corner is a tiny church the shape of a box, with an enormous blue sign that says GREENWAY CHURCH OF CHRIST.

And then, in small letters underneath:

TRY JESUS! IF YOU DON’T LIKE HIM, THE DEVIL WILL HAVE YOU BACK.

Dad pulls into a driveway and with a quick flick of his wrist turns the engine off.

“Are we visiting someone?” I say curiously, rolling down the window. “Or maybe picking up the keys to our super-cool Manhattan loft-with-a-view?”

There’s another silence.

And then I can feel it: sticky alarm rising from my feet upwards until my whole body feels full of something explosively panicky.