Полная версия

Picture Perfect

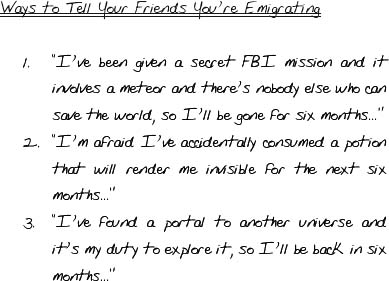

I knew I shouldn’t have used my new calligraphy pen to write the list. All the curly Es took ages.

My phone beeps, and my stomach does a sudden unexpected backflip like a maverick seal on YouTube.

You have such a vivid imagination, weirdo.

Can’t wait for next week.

A

And it’s as if somebody has thrown a pebble straight into the middle of me: panic starts rippling from it in small waves.

They start in my chest, and then they spread outwards. They spread to my shoulders, then to my arms and fingers. They spread through my stomach, into my legs and knees and toes until I’m full of undulating, pulsing ripples.

The waves get bigger and stronger and the pebble gets heavier and harder until everything inside me is threatening to spill out.

Which in a way it already kind of has.

Apparently thirty-nine per cent of the world’s population uses the internet, and Alexa is on every social networking site available. With a few clicks of a button, she has access to everyone.

There’s a knock on my door.

“Harriet?” Annabel says gently. “I just downloaded a meerkat documentary narrated by David Attenborough. I thought you might quite like it.”

Meerkats have really thin fur on their bellies so they can lie flat like sunbathers and warm up in the sun, and I’m intrigued to see what David has to say about that.

But right now, I just don’t care.

So I do the only thing I can.

“Oh, Nick,” I shout as loudly as I can into my dead mobile. “The monkey did what? How funny! Tell me more about it! You are just so hilarious.”

“Say hi to Nick from me,” Annabel calls through my door.

I don’t know why parents always want to send greetings vicariously. I think it’s their way of making sure they’re still watching us.

“Annabel says hi,” I tell nobody. Then I wait a few seconds in horrible silence. “Nick says hi back.”

“Great. I’ll go prepare your father by explaining that a meerkat is not, in fact, a real cat.”

Annabel retreats down the stairs, and I grab a slice of the chocolate cake she’s thoughtfully left on my dresser.

Eating cake on my own on my bedroom floor is not exactly how I planned to spend one of the biggest afternoons of my life.

But it’s the only thing left on my list I can still tick off.

1 eating cake

2 lying flat on my back, trying not to be sick

3 attempting to get brown icing off my duvet.

When I was in Japan I learnt that Buddhist monks in training must eat every single grain of rice in their bowl or it represents ingratitude towards the universe.

I’m pretty sure the same thing applies to chocolate cake.

The next thing I know, it’s 7am and the doorbell is ringing.

I sit up groggily and rub my eyes.

I’m still in my Spider-Man T-shirt, and there is a melted chocolate button stuck to my forehead. My phone is still in my hand, from where I fell asleep gripping it like a small, hard and square stress-ball.

“Annabel?” I shout. “Dad?” The doorbell rings again.

There’s a silence so – grumbling slightly – I grab my dressing gown off the back of the door and start plodding down the stairs: heavily, so my parents know that on the Day After My Big Day I cannot believe I am expected to get out of bed and operate as some kind of family doorman.

Then I swing the door open and stop scowling.

I knew Nick hadn’t forgotten about me. I knew the big romantic gesture was coming: I just had to be patient and wait for it.

I beam at the postman, and at the huge package he’s holding. Maybe it’s exotic flowers. Maybe it’s a carved African mask with a fascinating history, or indigenous jewellery with our names carved into a heart and—

“Are you going to take it or what?”

“Sorry?”

“I’ve got a lot of things to deliver, missy. Please sign here and let me get on with it.”

I don’t think this postman appreciates the level of grand romance he’s participating in.

“Approximately 360 million items are sent by post every year,” I say sympathetically, scribbling my name. “You must be very tired.”

The postman lifts his eyebrows. “I don’t deliver them all, love. I’m not Santa Claus.”

Then he marches off down the pavement without even looking back to appreciate the joy on my face.

The stamp is beautiful and exotic, and on the front is written in large, curly writing:

Which is a bit weird.

Nick gets on really well with my parents, but I think this might be taking integration a little too far.

I rip open the package, and pull out a small piece of yellow fabric that says:

A string of red beads that say:

A tiny pair of silver cymbals, engraved with a dragon.

Which sounds a bit dangerous. I’m not sure my father needs any help in that area.

Finally, I pull out a beautiful little engraved golden bowl with a cloth-covered stick.

This is the most inappropriate gift a boyfriend has ever sent anyone.

What on earth was Nick thinking?

Then I tip the package upside down and a card falls out.

Right now, mine feels like a milk float.

I turn the card over four times, just in case I’ve missed a pivotal piece of information. A code or perhaps a translator.

I’m just turning it over for the fifth time when there’s a heavy shuffling sound behind me.

Annabel pauses in dragging another suitcase down the stairs and flushes slightly. “Harriet, I didn’t expect you to be awake so early.”

I look at the suitcase, and then at the hallway. There are even more boxes everywhere; the bookshelves have been cleared; the taps in the kitchen are shiny. Dad’s loudly singing the wrong lyrics to ‘Don’t Stop Me Now’ by Queen, which is what he always does when he’s cleaning the oven.

“What’s going on?” I say, thrusting Bunty’s card at her. “Why is Grandma coming back? What adventure? And what does she mean by next year?”

Annabel goes a darker shade of pink and mutters, “Oh, God. Nice timing, Mum.” Then she clears her throat.

“Well, we were going to tell you yesterday, Harriet, but it was your big day – it’s all been very last minute – and …” She pauses. “Richard? Can you get out here, please?”

My eyes widen. Annabel never asks for Dad’s help in anything. Ever.

Through the kitchen door I see Dad use the cooker to pull himself up.

“Ouch,” he says, staggering into the hallway. “Maybe I should start doing yoga. Or pilates. Which is the most manly, do you think? Which would Batman do?”

“Can somebody please just tell me what’s going on?”

“Well,” Annabel says, going even more red. “There’s this thing … The fact is … Actually, you wouldn’t believe what’s … We were just thinking that …”

I’ve never seen Annabel unsure how to word anything before. It’s like watching a tiger paint its nails.

I look at the suitcases.

Then at the bulging cardboard boxes. The clear shelves. The cleanness of the kitchen. The masking tape and marker pens and Tabitha’s crib, dismantled and propped up against the living-room wall.

Oh sugar cookies.

They’re not cleaning at all.

They’re leaving.

“We have news, Harriet,” Dad confirms, grinning and putting his arm around my shoulders. “Massive news. Epic news. In fact, it’s the most epic-est news that’s ever happened ever.”

Epic-est?

“Will you please just tell me!”

“Harriet,” Dad shouts, exploding into the air like a firework: “WE ARE MOVING TO AMERICA!”

I’m desperately trying to piece that sentence into an order that makes sense, but it’s not working. AMERICA TO MOVING ARE WE. TO AMERICA WE ARE MOVING. WE TO AMERICA MOVING ARE.

With the best grammar skills in the world, they all kind of mean the same thing.

“B-but you can’t just leave me here,” I stammer. “I don’t know how to work the oven properly. I don’t know the code for the burglar alarm.”

“31415,” Dad says promptly.

“The first five numbers of pi?” At least that should be easy to remember.

“You’re coming with us, Harriet,” Annabel says calmly. “How ridiculous do you think we are?”

Dad has a piece of burnt pizza stuck to his knee.

I’m not going to answer that.

“But there isn’t time,” I state stupidly. “School starts next week.”

“It’s not for a holiday, sweetheart. It’ll be for six months, at least.”

“I got a job!” Dad shouts, jumping into the air again. “I’m going to be head copywriter at a top American advertising agency! I am no longer a draining sap on the life-source of this family!”

I thought Dad quite enjoyed sitting around in his dressing gown, losing his temper at people on the television and eating red jelly out of a big bowl.

“But when?”

“Tomorrow afternoon,” Annabel says, face getting blotchier by the second. “Sweetheart, we didn’t have a choice. It was that or they’d give it to another candidate. We’re leaving a lot of stuff here and Bunty’s going to take care of the house.”

I don’t think ‘Bunty’, ‘house’ and ‘care’ have ever been put together in a sentence before. She’s going to sell it, or burn it down, or cover it with glitter paint and glue feathers to the windows.

I’m definitely going to have to hide the cat.

“Your father’s new company is getting you a tutor,” Annabel continues gently. “That way you won’t miss anything and you can slip straight into sixth form when you get back.”

I blink at her a few more thousand times.

“Your father has to take it, Harriet,” Annabel adds when I still don’t say anything. “He’s been out of work for nine months, and New York will give him the break he needs. Plus –” she clears her throat – “we’ve, umm, run out of savings. We can’t afford for both of us to be out of work any longer.”

“New York? The job is in New York?”

What am I supposed to say?

That I’ve spent the entire summer making carefully laminated plans and timetables for the next academic year?

That I have a pencil case full of brand-new stationery I haven’t used yet?

That their timing couldn’t be worse and I hate them I hate them I hate them?

I’m just opening my mouth to say precisely all of that when I see a familiar expression on their faces. The Harriet’s-About-to-Throw-a-Tantrum look. The Hide-the-Breakables look. The We’ll-Need-to-Buy-New-Door-Hinges look.

And then I see what’s underneath it.

Under the nerves, they both look sad. Worried. Tired.

Dad’s excitement suddenly doesn’t look so real any more. It looks like he’s faking it, to try and make us all believe in it. Including him.

They don’t want to leave.

They have to.

“I think,” I say, taking a deep breath. “That I may need a few minutes to think about this.”

And – trying to ignore my parents’ astonishment – I turn my back, grab Hugo out of his basket and quietly walk upstairs to my bedroom.

Ever.

The first thing I do is lie on my bed with my nose in Hugo’s fur and try to slow-breathe, the way Nick taught me to for times like this.

i.e. when I’m about to throw a wobbler.

Then I sit up, grab a pad off my desk and slowly write:

Frankly, this should be the easiest list I’ve ever written.

It’s the eighth-biggest city in the world. It has 8,336,697 people and 4,000 individual street-food vendors. It has been the setting for more than 20,000 films, and it has the lowest crime rate of the twenty-five largest cities in America. The rents are some of the highest in the world, and the wages totally insufficient.

How do I know all this? Because I’m fascinated by the city, just like everyone else. And because every time I watch reruns of Friends I go online to try and work out how they all survive, financially.

This could be an enormous adventure. Bigger than modelling. Bigger than Moscow. Bigger than Tokyo. In six months, I’d become a local. A resident. One of them.

And I mean that quite literally. Thirty-five million Americans share DNA with at least one of the 102 pilgrims who arrived from England on the Mayflower in 1620. We’re pretty much blood relatives anyway.

Plus I’d get my very own tutor, who I will refer to as my ‘governess’. I could learn to speak Latin and sing about whiskers on kittens or spoonfuls of sugar and be gently guided by the hand through my formative years, learning to embroider.

But for some reason, I can’t make myself write any of that down.

Instead, I chew on my pencil and scribble:

My life is here.

This is my home.

Everything I love is here.

Nat and Toby are here. Nick is here, albeit sporadically. My dog is here, my school is here, my bedroom is here. My memories are here: the corner of the garden where Nat and I used to build forts out of bed sheets, and the washing line I trained Hugo with when he was a puppy, and the area that used to be an expensive plant before I ran over it with my tricycle.

My books are here, my fossils, my photo-montage wall, the cold dent in the wall I lie against when it’s hot in the middle of the night.

The road where Nick and I ran through the rain.

The bush outside where Toby waits for me.

The bench where Nat waits for me at the end of my road, in exactly the same position.

I love my life as it is, and I just want everything to stay exactly the same.

I chew on my pencil and stare at the wall.

Except … it’s not going to, is it?

Alexa has my diary, and humiliation levels at school are about to reach unprecedented levels. For the first time ever, I’ll have to handle her alone.

My modelling agency has already forgotten who I am.

I haven’t heard a peep from my former agent, Wilbur, for weeks.

Nick hasn’t called me.

And then my stomach twists uncomfortably.

Nat.

Because it doesn’t matter how many schedules and lists I write to try and keep us together, things are about to change. As soon as term starts, Nat is going to make new college friends and she’s going to start a new college life.

A life full of fashion people who know things about colour-coordination and handbag shapes; a grown-up life full of parties and shopping and coffee or something. A life where inventing codes and making choreographed dances in the living room just aren’t on the plans any more.

A life without me.

Pretty soon, the pigeon and the monkey are going to start wanting to fly and climb without each other, and the gap between us is going to get bigger and bigger.

Until one of us falls straight through.

Right now, I have a strong feeling that person is going to be me.

Slowly, I take my pencil out of my mouth and spit out a few bits of yellow paint.

And then – painfully, carefully – I write:

Dad sighs.

“She responded calmly, with thought and consideration. I’ve never been so frightened in my entire life.”

You have got to be kidding me.

Just once in fifteen years I respond to unexpected news in a mature fashion, and all I’ve successfully achieved is terrifying my parents.

“Ahem,” I say at the door. Maybe I should slam it a few times, just to reassure them.

They both look up.

“Wait,” Dad says, looking me up and down. “Why isn’t Harriet wearing an appropriately themed costume, Annabel? Where’s the top hat and walking stick and monocle?”

“Go on then,” Annabel says, nodding to the seat next to her. “Hit us with the Anti-American Powerpoint Presentation, Harriet. I’ve cleared a space on the table especially.”

She’s even got the extension lead out so I can plug in my laptop.

A little part of me wishes I’d given it a shot. Apparently twenty-seven per cent of Americans believe we never landed on the moon. That would have been a really excellent way to start.

I stand in the middle of the room with Hugo sitting quietly by my feet and clench and unclench my fists. I’m about to say goodbye to everything I know. Every person. Every brick.

Every piece of my life.

“Let’s do it,” I say. “Let’s move to America.”

“Oh,” Annabel says, dropping her head into her hands. “Oh, thank God.”

“It’s a trick,” Dad says, squinting at me. “I want to know where my daughter is, Mature Stranger. I bet she’s locked upstairs in a wardrobe. I demand you let her back out again in three or four hours’ time once we’ve had a nice quiet cup of tea and some lunch.”

I stick my tongue out at him.

“Oh, there she is,” Dad grins. “Phew.”

“Seriously?” Annabel says. “You’re not just saying that, Harriet? You really want to come?”

“Yes,” I say firmly. “I do.”

My parents both assess me with blank, surprised expressions. Then – in one seamless movement – they jump simultaneously off the sofa and tackle me into a hug with Tabitha tucked carefully between us.

“YESSSS!!” Dad shouts, grabbing my sister’s little hand and punching the air with it. “In your face, boring old England! The Manners are taking over Ameeerrricaa!”

I smile into my parents’ shoulders.

I can change my plans. But I can’t change my family.

And this way, I’ll leave everything behind before it gets the chance to do the same to me.

Instead, I opt for the truth.

The truth, and closing my eyes tightly.

When Nat is hurt, she gets angry, and when she gets angry she throws things. There’s a pair of high heels in close proximity, and there’s a good chance they are about to get wedged into me permanently.

Finally, I open one eye and peer cautiously through my eyelashes.

Nat’s still sitting on her bedroom floor, surrounded by a heap of clothes. Her first words when I entered the room were: “According to Elle I need a capsule wardrobe, Harriet. Twelve items that can be mixed and matched to create a seamless and coordinated outfit choice for any occasion so as to achieve maximum sartorial efficiency.”

There’s an endangered language in Peru called Chamicuro, and I think I’d have had more chance of understanding this greeting if Nat had just opted for using that instead.

“Are you OK?” I ask, after the silence that follows my bombshell.

“What do you mean you’re emigrating?”

Pink splodges are starting to climb up Nat’s throat and on to her cheeks. She’s gripping the sleeve of a jumper so tightly it looks like it’s about to get ripped off. “Like a … woodpecker?”

I don’t think Nat’s been paying attention to any of the recent documentaries we’ve been watching.

“Woodpeckers tend to stay very much in the same place, Nat.” I sit carefully on the floor next to her. “You’re thinking of King Penguins.”

“But … forever?”

“Well …” I may have slightly over-egged the pudding. “Not exactly forever. Six months, if we’re being precise.”

The pink flush climbs higher and higher until Nat’s ears look totally separate from the rest of her face, like Mr Potato Head.

And then – in one sweeping motion – she jumps up and the entire pile of clothes falls over.

“Oh my God,” she shouts, gripping her hands together. “Harriet, isn’t this just the best news ever? You’re so lucky!” Nat starts leaping around the room, picking things up and spinning dreamily around with them. “You’ll have your own doorman. You can eat hot dogs every day. You can find the grate where Marilyn Monroe’s dress blew up and copy her.”

“You can go to the Museum of Modern Art and study The Persistence of Memory by Salvador Dali,” a voice says from outside the bedroom. “I’ve heard it’s disappointingly small.”

I open Nat’s door.

“Toby, how long have you been here?”

“Long enough,” Toby says happily, wandering in. “Although this news does mean I’ll have to reorganise my stalking plans. Would you consider wearing a tracking device? That way I can just follow you online from the comfort of my own room.”

I stare at them in dismay.

Aren’t there supposed to be tears? Recriminations? How could you do this to me? and What is my life supposed to be like without you in it?