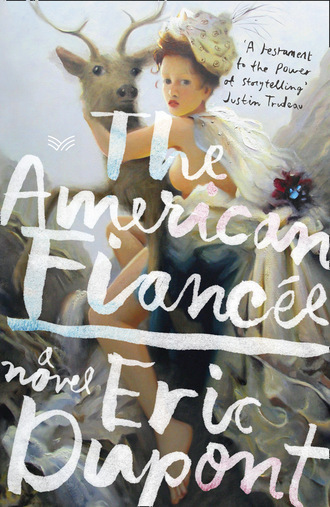

The American Fiancée

“Would you like another cup of tea, Father?”

“I wouldn’t be so impolite as to refuse,” he replied.

Truth be told, the priest would have happily taken some more ham, and perhaps a pancake, but he kept quiet, lest the woman take him for a glutton. Old Ma Madeleine stood up to refill the teapot in the kitchen. Walking through the door, she let out a cry.

“Louis-Benjamin Lamontagne!” she exclaimed.

The priest hoisted his 220 pounds up off the chair to see what was going on in the next room with his own eyes. There was Louis-Benjamin on a kitchen stool, holding the American girl by the waist as she sat straddled in his lap. The latter, as brazen as you please, had undone the second button of her suitor’s shirt, and was removing her hand from the boy’s clothing just as the priest’s head appeared in the doorway. Blushing with shame, the two children didn’t know where to look. The girl tried to free herself from the embrace of her fiancé who, for reasons only young men understand, reasons directly related to the spring breeze blowing through Fraserville that day, desperately wanted her to screen him for just another minute. He clung to her like a lifebuoy. Then suddenly he was infuriated. He grabbed hold of the girl with the firmness of a cowboy wrangling a heifer.

“I don’t wanna go to France, Ma!” he yelled in a tone Old Ma Madeleine had never heard before.

His mother stood there looking helpless, between the two entwined lovebirds and the priest, whose belly could now be heard rumbling. The priest had looked away from the young couple. He was now eyeing up the breakfast leftovers. He noted with no small amount of interest that there was a pancake on the griddle, untouched and still warm.

“You’re not going to throw that pancake out, are you?” he inquired innocently, pointing a finger at the object of his desire.

It was no time until the two youngsters, who had been only one word short of bliss, were united before God. For the fourth time that year, Father Cousineau sped things up a little, putting an earlier date on the banns, smoothing out the rough edges the hands of the authorities wouldn’t help but feel when they came across a young man still practically beardless but in possession of a marriage certificate. On April 3, 1918, before a sparse audience, Louis-Benjamin and Madeleine the American were pronounced man and wife before Father Cousineau, who was as proud as a peacock.

“That’s another one they won’t get.”

In the whole parish, he knew none finer, none sweeter, than the young Lamontagne boys. The very idea that such a handsome young man would have a bomb dropped on him or, worse still, be sent home an invalid or gassed simply because the king didn’t know how to wage a war, was abhorrent to him. Old Ma Madeleine thought it best to wait until her husband had returned home from the logging camp before doing something so momentous for all concerned, to which the priest retorted that the army spotters could step out of the train at any minute or spring up like jack-in-the-boxes on the road. And once they were in Fraserville, there would be nothing for it but to hide her boys like hens hide their chicks. The priest was thinking that, judging by what he had heard from Louis-Benjamin at confession, the young American girl was about to feel a spring wind blow, the likes of which she had never felt, or at least find reward for all her attentions in the kitchen. With the resignation of the birds, Old Ma Madeleine, sitting stiffly in a pew, shed not a tear, tears not being her forte, and wondered instead how she was going to explain everything to her husband when he came back from the logging camp at winter’s end. Piled in beside her in the freezing-cold church, Louis-Benjamin’s little sisters dozed, stared at the Madonna out of the corner of their eyes, or counted the cotton flowers stitched onto Madeleine the American’s white dress, which had been hastily rented the day before from the Thivierges’ general store, meaning that Old Ma Madeleine had been up part of the night adjusting the waist (much too ample for such a tiny slip of a thing) and ironing her girls’ calico dresses. Her face wan and her head filled with sleep, Old Ma Madeleine entrusted the fate of her oldest son to the hands of God and the wedding photos to Lavoie the photographer.

Their wedding photo—the one that Papa Louis is pointing to with an insistent index finger at this very moment, right beside the photo of Sister Mary of the Eucharist’s twin sister who died in Nagasaki—shows the newlyweds in profile, still almost children, Louis-Benjamin with his cowlick standing straight up in the air and smiling blissfully, perhaps because he was wearing a bow tie for the very first time, perhaps because his dearest wish was going to be realized when he walked out of the photographer’s studio on Rue Lafontaine, which the bridal procession had entered headed up by Old Ma Madeleine, followed by her girls, each in their Sunday best, then the main attraction, the undisputed superstars of this strange Easter carnival. The photographer had them sit very close to each other, close enough for the girl to feel on her neck the breath of the strapping Louis-Benjamin doing his level best not to go mad with happiness. They were like two children dressed up as adults to get a laugh out of their parents. The collar on Louis-Benjamin’s shirt was slightly too big for him, his bow tie almost as broad as his smile. As for the girl, she looked like she’d just been told a risqué joke. The blissfully happy expression that was to mark that day still shone clearly in December 1958 in Papa Louis’s living room, in the soft light of the fringed floor lamp that enveloped with its yellow glow the storyteller, his children, a still-decorated Christmas tree, and, at the back of the adjoining parlor, Sirois in his casket. Little Madeleine felt her brother Marc’s hand under her thigh, a restless, mischievous, reassuring presence.

Her mind swimming back and forth between two distinct worlds, Madeleine took her brother Marc’s hand so as not to lose him, so as not to be ejected from this downy nest confected from Christmas trees, gin, little brothers, and stories of brides arriving by train on a winter evening. She wanted to know how Papa Louis had come into the world, because that’s what he’d promised to tell them: how he had come into the world against all odds that Christmas of 1918. She wanted to hear the story just once, then grow up.

“Hold my hand. I don’t want to fall asleep,” she whispered into Marc’s ear.

As if to celebrate the impromptu wedding of Louis-Benjamin and Madeleine the American, Papa Louis lit a cigarette, twirling it several times before going on with the story. The air in the living room filled with an acrid, carcinogenic smell, lending the room a solemn feel, as though Papa Louis had wanted to show they had moved into the adult world and the story was about to get darker. He closed the door to the parlor where Sirois was resting.

“Cigarettes are bad for the dead—and for the living!”

He slapped his broad thighs. Old Ma Madeleine had set up a bedroom for the newlyweds in her home on Rue Fraserville. What is there to say about Louis-Benjamin other than that his boss, Old Michaud, saw all his wishes come true in the first week after the wedding ceremony. The boy had rediscovered his composure and constantly wore a little smile, the one he was known for before the American arrived. In Old Michaud’s workshop, he carved and sanded down one little cradle after the other. His young wife had been caught throwing up into a wooden pail one morning, looking gloomy and preoccupied. In the meantime, Vilmaire Lamontagne, Louis-Benjamin’s father, had returned home from logging over the winter to find his son married to an American. He had arrived back one rainy afternoon to a deserted house. Alone in the kitchen, a young lady was busy preparing rabbits. Vilmaire asked what she was doing in his kitchen. The stranger put down the carcass, rinsed her hands, and tried to sum up in her stilted French the events of the previous weeks. He looked at his daughter-in-law, perplexed and a little worried. The newcomer served him a bowl of hearty stew and a mug of tea. Tired after his long journey, he chewed on his meal as he looked the young woman over. Little Louis-Benjamin married? Where had his wife gotten to? And the girls? All these questions were answered after a long nap when the rest of the family came back from yard work at a cousin’s house. When it was confirmed to him that his son was indeed married, Vilmaire Lamontagne smiled, looked the American up and down, and lifted her up off the ground as though checking her worth in weight.

“You’re my daughter now.”

The summer went by in a state of bliss that was barely interrupted by the pregnancy troubles of the young wife, who substantially increased in volume. On the days her husband received his pay, she would be seen wearily dragging herself back up Rue Lafontaine from the stores. Louis, for his part, had been thrust by his father into the world of woodwork. A similar-looking home was built beside his father’s because they were starting to get under each other’s feet. That September, Father Cousineau started putting in appearances again with the family. They had long since understood that the man had to be fed regularly, if only to express their gratitude to him for having spared Louis-Benjamin a senseless death at Verdun or Vimy. Father Cousineau rather enjoyed being in a dining room teeming with snot-nosed children. The Lamontagne home was a place of comfort, a refuge that allowed him to escape, if only briefly, the cold, impersonal surroundings of the presbytery. On such evenings, he was especially fond of recalling his days at the Rimouski seminary for the Lamontagnes. He had been ordained there, hailing from the nearby Matapédia Valley as he did. He spoke of the camaraderie among the seminarists, without, of course, going into all the details of the special friendships that tended to flourish.

Ten years before being sent to the parish of Saint-François-Xavier in Fraserville, Father Cousineau had belonged to the seminary’s theater troupe, where he had spent his happiest hours. Aside from the pleasure he felt performing scenes from Lives of the Saints or the New Testament, Cousineau really came into his own making sets and costumes. People in Rimouski still remembered the grandiose outfit he had made himself to play King Charles VII in The Maid of Orleans, a pious drama penned by two Brothers of the Holy Cross in 1882 that paid tribute to the victorious king who had managed to rid France of the English plague. For his court costume, young Cousineau had made himself a magnificent doublet from maroon felt, trimmed around the collar and sleeves with fox fur he had begged one of his aunts for. A talented couturier and designer with a keen fashion sense, he hadn’t stopped there: he had also made himself a large black hat with a broad brim upon which he had painstakingly embroidered the white lines that make up the starred pattern of that particular historical headpiece. He drew much of his inspiration from a portrait of the French sovereign that appeared in Lives of the Saints and even went so far as to wear old-fashioned stockings—borrowed from the same aunt who had loaned him the fox fur—under the salmon-pink petticoat breeches that made him vaguely resemble a peony and, the one and only anachronism in his otherwise wholly convincing attire, Charles IX shoes that had also served the year before when the senior students had put on Le Malade imaginaire.

The troupe of seminarists gave the actor who had triumphed as Toinette in Le Malade imaginaire the role of Joan of Arc in The Maid of Orleans. The irony being, Father Cousineau remarked, that the Brothers of the Holy Cross, who had written the play, had included one rather lengthy scene depicting the trial of Joan of Arc, particularly her indictment, in which she was reproached, among many other offences, for wearing men’s clothing. So it was that when the young seminarist played this role dressed up as a woman, a sigh or gasp always went up from the audience, as a train of thought arrived in the station. But in The Maid of Orleans, Father Cousineau had stolen the show from the cross-dressing seminarist thanks to his magnificent costume and the deep voice he had used to reply to Joan of Arc when she was crowned.

“Your Majesty, we absolutely must take Paris. Our victory is unimaginable without Paris.”

“Joan, above all else we must be careful,” Charles VII had replied, under the approving gaze of the audience, Cousineau’s presence so eclipsing poor Levasseur that people almost began to hope he would be burned as quickly as possible.

And so Father Cousineau belonged to those who you could say had missed their vocation in life, even though his Sunday mass attracted four to five hundred souls, rain or shine. To a liturgy as regular as clockwork and in which there was on the face of it no place for creativity or improvisation, the ingenious Father Cousineau always found a way to introduce a dash of theatricality to the proceedings, as though the popes had not already personally seen to it that Catholic mass remained the best show in town. On the feast day of St. John the Baptist, for instance, Father Cousineau made sure that the altar boys were all very young, with curly blond hair. He had arranged it so that the Sisters of the Child Jesus, newly arrived in Fraserville, joined a very active choir that parishioners would turn out to hear at the drop of a hat.

And so it was that on Sunday, November 17, 1918, a very special mass came to be sung at the church of Saint-François-Xavier. Father Cousineau, always with a keen eye for staging and an ear for music, had demanded that each parishioner be at the mass, adding that absentees had better be on their deathbeds. They were going to give glory to God, ask forgiveness for their sins, and praise the Virgin Mary for having brought an end to an interminable war, a senseless, horrifying war, and no grounds would be deemed acceptable for failing to attend the ceremony. Without a word of explanation to the parishioners, Father Cousineau asked the couples he had personally married during the war to fill the first pews, thereby upsetting an established order determined by how much the faithful had contributed to the parish finances. He had also tasked the choirmaster with having the choir sing a Te Deum, a hymn sung on various occasions, notably at the end of a smallpox epidemic or whenever a siege of a city had been lifted, an heir to the throne had been born, spring had arrived after a particularly deadly winter, a shipwrecked crew had been saved, a harvest of oats had been especially bountiful, or an end had come to a war that no one had wanted and that had brought nothing but death, sadness, and pestilence down upon humanity. Father Cousineau’s sermon was clear: “My fellow Canadiens! Go forth and have children to replace those the war has taken from us!”

And he addressed his message to the first rows of the congregation in particular, for the most part sprightly and willing young men married to very young women deprived of all means of contraception.

The Te Deum was magnificent. Papa Louis chanted in Latin to impress his children:

“Te æternum Patrem omnis terra veneratur!” he sang in a tuneful tenor. “What does it mean?” chorused the children, who belonged to a time where people still wanted these mysterious phrases translated.

It means, “All the earth doth worship thee, the father everlasting!” Papa Louis replied, proud to prove that not only was he able to lift a horse clean off the ground but he could translate from the Latin, too.

In a way, the parishioners, and especially those whom Father Cousineau addressed on that first Sunday following the armistice, were singing for their priest a silent hymn full of thanks to a man who, through some sleight of hand, falsification, and manipulation had managed to unite before God and man an unrivaled number of couples, a good many of whom had not yet reached adulthood. With their chubby, smiling faces, not the slightest grey hair among them, their hands still plump, sometimes already expecting, unsuspecting though they were, they wanted nothing more than for the interminable mass to end so they could get on with the task Father Cousineau had set them in the intimacy of their wooden homes. Everyone would remember the impeccable organization behind that armistice mass, the emotion that had washed over the congregation, and Father Cousineau’s touching affection for young people, family, and music. Could there possibly be, east of Quebec City, a parish priest more pleasant, more determined, more kindly? They had their doubts. At any rate, in the hearts of Louis-Benjamin and the American, Father Cousineau was truly a savior, a guardian, an indispensable guide.

But Cousineau still had an idea or two to ensure his masses would live long in the memory of his congregation, masses as unforgettable as opening night at the theater. It goes without saying that he considered Louis-Benjamin and the American something of a creation of his own making. From one Sunday to the next, he could see how the pretty American was thriving, developing more curves, and illuminating with her hopeful face the gazes of the other parishioners. With her bulging belly, rosy cheeks, and glowing complexion, the American exuded maternity and joy. According to the priest’s calculations, she would bring her child into the world after New Year’s Day, which gave him cause to consider realizing a dream he had cherished for years: a live nativity scene at midnight mass. Never had he dared bring up this desire with any of Fraserville’s young couples, fearing they would refuse outright or misinterpret his intentions. But he was so close to the American, and young Louis-Benjamin was, out of all his flock, the closest thing to the son he would never have. And so in September he revealed his plans to them. It wouldn’t be a big deal for Louis-Benjamin and his young wife: between the ox and the little donkey they would come in from the sacristy and walk calmly toward the altar. They would, of course, be appropriately attired, faithfully harkening back to the days of the nativity.

“With real lambs, I promise!” Cousineau had assured them.

He had already spoken to a farmer on Témiscouata Road, who had agreed to supply two of them. They would be led by young shepherds, the same who had played the role of Saint John the Baptist.

“There will be singing, and music, Bach, Balbastre . . . Fraserville will still be talking about this mass in one hundred years’ time!”

In the Lamontagne household, the thought had brought a smile to the little girls’ faces, already imagining their big brother as Joseph and his wife as the Virgin Mary. Old Ma Madeleine immediately expressed her clear disapproval: the young woman would likely not be able to live up to the priest’s ambitions. And it would cause the whole parish to turn its attentions to the pair when all eyes had already been on them for months. At any rate, if the project were to go ahead, it would do so without her consent.

“People are talking. Saying the girl was put in the family way by my Louis-Benjamin before the wedding.”

What Old Ma Madeleine did not know, but what anyone in the parish could have told her, was that that was the most harmless rumor doing the rounds about Madeleine the American. The town gossips had come up with whole new chapters for the tall tales surrounding her origins and the real reasons why she had turned up in Fraserville.

Nobody had officially bought the story of the family decimated by Spanish flu. For scandalmongers, the idea that Madeleine the American had been a victim of circumstance was much too bland. It didn’t fit with the story they had already scripted for her and so they came up with two explanations for her pregnancy. The first had it that the child had been conceived out of wedlock, the very night the American first set foot in the Lamontagne home. The sorry reputation the women of America held in Canadian eyes only added fuel to the fire. An American! Just imagine! The young lad had surely been seduced from the first minute by the red-haired devil. Two reliable witnesses had even seen them kissing on the lips, right under the noses of Old Ma Madeleine, Father Cousineau, and Louis-Benjamin’s little sisters, whose salvation had surely now been compromised by such debauchery. They would have to be watched carefully. But that was far and away the least hurtful of the tall tales circulating along Rue Lafontaine.

There was much worse.

Among the many stories Old Ma Madeleine had never heard about her daughter-in-law was the vile rumor that she had come to Fraserville already carrying the child whose paternity was now being ascribed to Louis-Benjamin. It goes without saying that this version nicely complemented rumors that the American had led a loose life before repenting and winding up in Fraserville. The rest was said to have been a ruse on her part: she seduced Louis-Benjamin, they said, so that he would raise the child whose real father would never be known. At any rate, Old Ma Madeleine was against the idea of a living nativity and did not mince her words. Louis-Benjamin’s father, for his part, was completely indifferent to the whole affair. Only the little Lamontagne girls seemed keen on Father Cousineau’s project. Perhaps they would be allowed to take part themselves?

“The angels are boys,” Old Ma Madeleine snapped, nipping in the bud her daughters’ dreams of the theater.

Louis-Benjamin’s young brother Napoleon wanted to know if they needed a shepherd, making it clear to the priest that any support for his project would come from the youngsters. Louis-Benjamin and the American had laughed long and hard at the priest’s plan and were largely in agreement, provided they had very few lines to deliver. The priest had reassured them immediately: they would have very little to say; the whole thing would be narrated by a nun from the Sisters of the Child Jesus, who would read the story of the nativity from the gospels. This eased the American’s mind in particular. Her hesitant French caused her to blush every time she had to speak in public.

The priest remarked that the young woman was wearing a very simple gold cross on her ample bosom. He had not noticed it when she arrived in the spring. Perhaps it had been hidden by layer upon layer of clothing. But now he could see it shining in the light. The cross was about an inch long and made from real gold. Seeing the priest staring at the piece of jewelry, the girl tried to explain its provenance in French peppered with English. Louis-Benjamin had given it to her for her birthday, on June 24, the feast of St. John the Baptist. She unfastened the gold chain and handed it to the priest, saying, “Could you please bless my cross, Father Cousineau?” The priest fingered the pendant. There was an inscription on the back, its owner’s initials in cursive script: ML. The priest, well used to being asked to bless entire farms, new homes, telephones, and even locomotives, didn’t think twice about blessing the piece of jewelry, especially since he felt that by performing this simple task for the naive little soul, he would surely improve the odds of her taking part in his living nativity. He blessed the small cross and returned it to its owner, pink with gratitude. How much must it have cost? Much more than Louis-Benjamin was earning at Old Michaud’s, that was for sure. But Louis-Benjamin had not let material considerations dampen his ardor for his Madeleine. The cross was brilliant, scintillating proof of it. The priest told the American to be very careful, to never go out in the evening wearing her cross too ostentatiously, and to take good care of it.

“I will, Father Cousineau.”

Much to Old Ma Madeleine’s chagrin, the deal was sealed quickly. They agreed on a dress rehearsal in December, and then the meal was served, to Father Cousineau’s great delight. At last he would have the midnight mass he had always dreamed of.

Father Cousineau thought about his living nativity every day, had costumes made, sat down with the nun to decide on which text to read, did everything in the church to make sure the scene would have every bit the impact he hoped for, even for those who would be sitting at the back or standing. The American was now enormous. She dragged herself with more and more difficulty from one chore to the next. Sometimes she would be caught sleeping on a stool, her head leaning against the kitchen wall, as the soup she had begun to heat up boiled over. On days like those, Old Ma Madeleine would excuse her from all strenuous tasks and order her to remain seated or lying down, to keep away from the stove at any rate, a miserable sentence for a woman used to cooking morning, noon, and night.