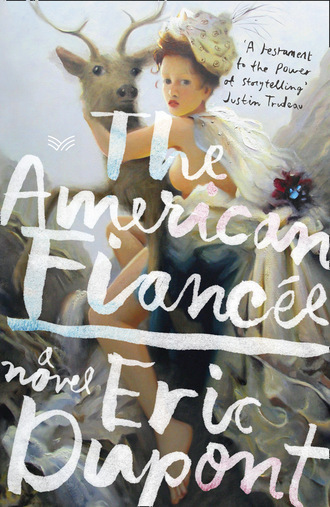

The American Fiancée

With a wave in his hair that, on particularly windy days, transformed into a small tuft, with the long eyelashes inherited from his mother, with shoulders as broad as an ox, with his pale complexion and cheeks turned rosy by the cold, the young man, had he not already been promised to the American lass, would have had no trouble at all finding a wife for himself from among Fraserville’s six thousand souls. The catch was that she had to be called Madeleine, a condition that disqualified the vast majority of admirers at a time when, as Papa Louis put it, “No one ever dreamed of changing their name.”

“You were born Louis, you died Louis. Not like young what’s-her-name. That Norma one who calls herself Marilyn for the movies. Anyhow, if the girls of Fraserville had known that just by changing their name the way Fraserville changed its name to Rivière-du-Loup in 1920 they would have stood a chance of catching young Louis-Benjamin’s eye, well they’d all have changed their names to Madeleine overnight. He was a good-looking young lad, was your grandpa!”

And yet Papa Louis had been through his fair share of name changes himself. Papa Louis might have been born Louis Lamontagne, but then he became Louis “The Horse” Lamontagne—the name everyone throughout the region respectfully called him as soon as he started performing public feats of strength—then, once tamed by Irene Caron, Papa Louis it was until the day he died. Between “The Horse” and Papa Louis, there had been, depending on where he found himself, other nicknames: The Incredible Lamontagne, Cheval Lamontagne, The Great Canadian, and others that had never reached his ears. But he was still yet to be born in his own story.

“Papa, it’s complicated enough as it is . . .”

And so it was a bolt out of the blue, or its Nordic equivalent, a Northern Light, that marked the first encounter between the sturdy Lamontagne boy and Madeleine the American as she took from her purse the photograph of Louis-Benjamin sent by Old Ma Madeleine. The American looked down at the photo, then up at its model, then back down from the model to her photo. Her face lit up as though she had just seen an apparition. With not a thought for good manners or the rules of etiquette, Louis-Benjamin scooped up the traveler as if to see how much she weighed, like he did with his cousins and sisters several times a day to build his strength, the little girls having become something akin to living dumbbells that had only to be caught as they ran by. Louis-Benjamin held his new bride tight against him, because this was the girl he would marry, the doubt in his mind having several minutes ago given way to a certainty as implacable as winter, as strong as the squall from the east that had just picked up in the starry night. The bride’s feet floated a foot off the ground, like those of an angel in flight. During the warm but brief embrace, Madeleine felt through her marten fur coat precisely why she had been summoned from so far away. When he set her back down onto the ice, a giggle could be heard; then Madeleine said in the prettiest New England accent:

“I see you’re happy to meet me.”

She spoke English. Old Ma Madeleine coughed, cleared her throat, and inquired:

“Vous parlez français, Mademoiselle?”

By way of response, the young lady twirled around three times, gazed up into the starry sky, and sang in a thick American accent: “À la claire fontaine, m’en allant promener . . .” Jaws dropped to the floor. Father Cousineau piped up in English. He explained to the girl that she must be on the wrong car: they were waiting for “a French girl” promised to “this young Catholic man.” The young Catholic man felt as though his heart was about to burst through his ribcage and explode into the March night. Madeleine was still laughing. She produced a letter from her purse and handed it to the priest.

My dear sister,

We were glad to hear from you. Your letter arrived yesterday. We were sad to learn that Louis-Benjamin lost his bride. We understand his grief and sorrow. The flu is also killing many here in New Hampshire. Thank you for your good intentions for our little Madeleine. You are right. We adopted her in 1909 after the death of her parents, who were from the Beauce region in Canada. She will make a perfect little wife for your Louis-Benjamin. She is very happy to go live in the land of her natural and adoptive parents. She was baptized in the one true Church and still understands the French from back home. She will turn seventeen this spring, and I told her all the men in the family make good husbands. I entrust her into your care and into the care of your son, whom I imagine to be as fine a person as you are, my dear sister. May they be very happy together in our beautiful Canada!

Your brother, Alphonse

Illiterate though she might have been, Old Ma Madeleine demanded to see the piece of paper as if able to detect some detail the priest had missed.

“It’s not exactly what I was expecting!”

Louis-Benjamin paid no heed to the details. He was already tossing the American girl’s bags up into the priest’s sled, followed by his sisters, one by one, like bales of hay. He plunked the American lass down between two of the girls to keep her warm. The journey to the lower end of town went by in a silence that held a different meaning for each of the sled’s occupants.

Back at the Lamontagne home, Old Ma Madeleine required all her maternal authority to separate Louis-Benjamin from his bride—as he now considered her—come bedtime. They realized, after dropping the priest off at the presbytery, that the young woman did indeed understand French, but there was absolutely no way she had been born into a French-Canadian family that had recently immigrated to the United States. Where did her red hair come from? And the freckles and teal eyes?

“She looks more like a Scotch!” Old Ma Madeleine had remarked in a fit of pique.

Scotch, English, or Irish, the newcomer was clearly of Nordic descent. All she would ever say on the matter was that she had been born in New Hampshire in 1900, she was as old as the century, and she had been adopted by a French-Canadian family at the age of nine, which led people to believe she was probably Irish Catholic because the Americans would never have put a little Protestant girl in the hands of a hopelessly papist French-Canadian family.

In Fraserville, news of the American girl’s arrival spread like syphilis through a Berlin whorehouse. Fraserville was never one to pass up on a bit of gossip. The finest idle tongues from up and down the town relayed the tale like an Olympic torch. After the inevitable laughter sparked by the story of the young girl’s arrival in response to a simple letter from Old Ma Madeleine inquiring if a daughter-in-law might possibly be available, each had his or her own interpretation of events. And so it was that a great many extravagant rumors did the rounds about Madeleine the American, only three of which survived until that night of December 28, 1958, in Papa Louis’s living room.

According to the first version of the story peddled in the parish of Saint-François-Xavier, the Lamontagnes had fallen victim to a dastardly plot hatched by Old Ma Madeleine’s brother. There must have been vengeful thoughts behind it, because who sends his own daughter, adopted or not, hundreds of miles away into the arms of a stranger? The young woman must have been insufferable; her adoptive parents had jumped at the first chance they got to be rid of her once and for all. Now who knew what might happen? And Louis-Benjamin would be left to pick up the tab.

The second version of the story, perhaps a little more refined and more shrouded in mystery, cast Madeleine the American in the role of a woman of passion, flitting from one widower to the next unsuspecting bachelor, amassing inheritances and leaving funeral processions and grieving families in her wake. She had, of course, stolen Old Ma Madeleine’s letter at the post office, before having someone pen a reply to take in the Lamontagnes. Old Ma Madeleine would have only to perform the usual checks by telegraph in order to be clear in her own mind and be rid of the parasite. In its darkest versions, this story prophesied an accidental death for Louis-Benjamin in the near future. All bets were off.

And finally, more twisted minds ascribed darker intentions to the little schemer. Probably a lady of the night, she had, they said, met Madeleine the American on the train, made sure she was well and truly out of the picture (there’s just no stopping those kinds of vermin), and taken her belongings to organize the whole sorry sham. The rest was nothing but theater and strength of conviction. No matter, uniformed men would soon be arriving to write an epilogue to the improbable tale.

“No one ever got to the bottom of it,” sighed Papa Louis, staring at his glass of gin.

The following day, March 2, Old Ma Madeleine wrote to her brother Alphonse, demanding an explanation for the previous evening’s events. Who was this girl? Had he really sent her packing to a foreign land without even inquiring as to the worth of young Louis-Benjamin? Was the young lady really that docile? Was he absolutely certain he had made the right decision? In the meantime, the American girl would have to be housed somewhere. Neither the Sisters of the Good Shepherd nor the Sisters of the Child Jesus had room for the poor thing. As for the priest, it was out of the question that he put up such a strange creature about whom virtually nothing was known and from whom the most surprising revelations might well be expected. And so the Lamontagnes resolved to let her stay with them. From the day after she arrived, the girl began to behave in a most unusual manner. First of all, she confirmed by way of a particularly nasal early morning rosary that she was indeed of the true faith. Then, every morning at the crack of dawn, she would cook dishes the Lamontagnes were not in the least used to. On the first day, she went to the general store for provisions since it appeared she had brought a modest dowry with her from the United States. On the second morning, she set to work in the kitchen, humming all the while a heartwarming song for the cold of heart:

Will you love me all the time?

Summer time, winter time.

Will you love me rain or shine?

As I love you?

Will you kiss me every day?

Will you miss me when away?

Will you stay at home and play?

When I marry you?

The little waltz in three-quarter time was so catchy that it stayed in your head for hours after hearing it. Papa Louis sang it for his audience, which was beginning to shrink as time ticked on. Luc was now asleep, collapsed on top of his brother Marc, who was himself fighting a battle of epic proportions against Morpheus. Madeleine, eyes wide as saucers, was gripped by the tale of horses and deadly epidemics and entirely under the storyteller’s spell. She hummed along to the American girl’s song, which their father sang to them in their little beds at night. The whole of America, a whole century, used to fall asleep to this lullaby that sang of worry, doubt, promises, and love.

Marc watched his sister Madeleine’s head nod gently as she began to drift off. He was suddenly gripped by a terrible fear: Papa Louis, realizing his audience was asleep, would bring his story to an end so that he wouldn’t have to pick it up again the following week. The boy was dying to hear what happened to his grandparents next.

“Madeleine, go make Papa Louis a gin!” he cried, shaking his sister like a plum tree.

Madeleine went off to mix the toddy.

“But what did the American girl cook?”

The question came, once again, from the kitchen.

“Breakfast. Pancakes, beans, fried eggs, you name it! And the people of Fraserville had never known the like of it,” Papa Louis replied, gazing off into the distance.

The American had gotten it into her head that the way to Canadians’ hearts was through their stomachs. But she would have her work cut out for her. Without ever having read it, she knew full well the contents of the letter Old Ma Madeleine had dictated to the parish priest the day after she had arrived. They would have to be won over one by one, calorie by calorie, carb by carb . . . On the third day, the American girl baked a sandwich loaf that relegated Old Ma Madeleine’s bread to the rank of mere ship’s biscuit. That American bread was white and fluffy as a cloud. It caressed Louis-Benjamin’s lips like the wings of a dove. On the fourth day, the girl baked hot cross buns topped with caramelized sugar. Their aroma alone had the young man foaming at the mouth from the woodshop where, as Old Michaud’s apprentice, he crafted small, simple pieces of furniture to order for the people of Fraserville. Cribs more than anything else. And always to the melody of Will you love me all the time?, which the parish priest had agreed, after much beseeching and imploring, to translate, whispering into his ear so that people would not think he had succumbed to an unspeakable, unnatural vice before the handsome Louis-Benjamin. The aroma of the hot cross buns, the American girl’s red hair, the baby cribs, Will you love me all the time? . . . It was all enough to make his head spin. The poor boy, who had never known the torments of love, was so distracted he flattened his thumb with a hammer. The cry of a wounded animal reverberated from one side of the St. Lawrence to the other. On the north shore, people thought it was the cry of a drowning man, and a search was launched on the snow-covered ice of the enormous river for the poor devil who had fallen into the water.

But the drowning man was Louis-Benjamin . . .

“Drowning in an ocean of love!” exclaimed Papa Louis, beating out each syllable with his left hand on the arm of his chair.

On the sofa, the peals of laughter from Madeleine and Marc were almost enough to stir Sirois from the dead. Luc remained buried in his impenetrable sleep, his body occasionally convulsed by a passing bad dream.

Old Michaud was saddened to see the young man so devoured by desire. How many times had he tried to reason with the lad? He even went as far as to explain that sometimes burning blazes could be snuffed out, temporarily at least, and that it sufficed to find some place or other where you could be certain of being alone to “plane the big beam” until your ears buzzed. Louis-Benjamin listened politely to the fellow’s advice, not daring to admit that, in this particular case, a mere plane would be but a droplet of water on a burning stone. He confessed to his master that he was considering eloping with the American girl to marry her in another parish, before a priest who did not know them. Old Michaud explained to him that the plan was destined to fail, that he would only bring disgrace upon himself, and that, in any case, no priest in the province of Quebec would agree to marry a young tenderfoot to a mere slip of a girl without their parents’ consent. When he saw the young boy’s eyes fill with water, Michaud promised to put in a word for him with the priest. He himself had no idea what this initiative might bring, but speaking to the priest never did any harm.

Father Cousineau received Old Michaud just before mass. Michaud tried to find the words to make the man of the cloth understand that young Louis-Benjamin was languishing with love for the young American girl and that the nuptials between the two lovebirds should be celebrated without delay. He himself had taken a wife at nineteen; it wasn’t at all out of the ordinary. He also tried to get the priest to understand that some trees grow more quickly than others, an allusion that was somewhat lost on him. Nevertheless, Michaud added that his main concern was getting the boy back to working at the same pace he had been at before the American girl arrived. Nothing less than a marriage before God—and before Pentecost—would settle the matter. The priest waited patiently for Old Michaud to finish. At the end of the discussion, he invited the cabinetmaker to pray with him for the intervention of the Blessed Virgin. Before leaving, Michaud made an offering to the parish, which, that day, took the form of a sugar pie his wife had baked that very morning, knowing that her husband was off to the presbytery with a request. It was only fifteen minutes until the start of mass. Taking one look at the pie, the priest calculated that by sending Michaud on his way and hurrying just a little, he might have time to eat just the tiniest slice, Lent or no Lent. Old Michaud walked into the church, and when the priest appeared in the sacristy five minutes later, he still had crumbs on his belly.

The sermon was sweeter than usual.

Meanwhile, Old Ma Madeleine was at her wit’s end. On the one hand, the young American was as nice as could be, showed an uncommonly healthy appetite for work, and had won the approval of Louis-Benjamin’s young sisters, with whom she shared a room. She helped the girls get dressed in the morning, braided their hair, kept them clean, and taught them good manners. To say thank-you. To clear the table. To smile. On the other hand, no one knew the first thing about the woman. Where had she come from? Why hadn’t she learned French like everyone else? Had Alphonse’s family taken to English to fit in better in the United States? And what about the girl’s past? Was she going to transmit some terrible disease to her Louis-Benjamin? And in the improbable event she agreed to hand over her oldest son to this mysterious American, would their children grow up to look down on their Canadian father?

One month passed. Then, on the morning of April 2, Easter Tuesday, Father Cousineau knocked on the Lamontagnes’ door, holding a letter mailed in New Hampshire. The torn envelope was proof that the priest had already read and translated its contents. Delicious aromas wafted in from the kitchen. Eggs, Father Cousineau was quite certain, and unless he was mistaken, fresh bread, baked beans, cretons, some kind of pork glistening with fat, and a full and generous teapot were standing by. The American girl was at work. He noted happily that everyone in the Lamontagne family appeared to have gained weight, even though Lent had just ended. Well-rounded cheeks, tight clothes, generous bosoms . . . Old Ma Madeleine’s sons and daughters had spent an anti-Lent to which the American cook’s arrival was surely no stranger. The breakfast table had not yet been cleared when Madeleine the American asked the priest to take a seat. “Please, Father . . .” She disappeared into the kitchen, returning with a plate piled high with pancakes, eggs, and slices of ham. All swimming in a half-inch of maple syrup. The priest, a man used to a leaner diet, dug courageously into the mountain of treats that towered before him. The rich food gave him the courage to announce the news he had come to tell the Lamontagne family. While continuing to eat—because, truth be told, he had never tasted pancakes so fluffy, so light, nor ham so tender—he first asked to speak to the American girl alone. The rest of the family piled into the kitchen. Three of the children spilled out onto the lawn to play in the early rays of the April sun.

From the kitchen, the priest’s low voice could be heard as he spoke hesitantly in the English he had learned at the seminary. It went on for some minutes. Then a prayer went up. Next, after a short silence, three sighs from a woman were heard, followed by a sob. Upon hearing the sobs of the woman he so desired, Louis-Benjamin wanted to burst into the dining room and take her in his arms. Old Ma Madeleine looked daggers at him. “You stay put!” she hissed at her excitable son. After a moment’s silence, the girl swept into the kitchen, her face streaming with tears, sobbing uncontrollably. Intrigued, Old Ma Madeleine and her son went over to the priest, who was busily mopping up his yolk with a slice of toast. He wiped his mouth before he spoke.

He had received a letter from the United States, penned in English by the priest in the girl’s parish of Nashua. Shortly after their adoptive daughter’s departure, Alphonse’s family had suffered much misfortune. First, their youngest son had been struck by a terrible fever that no remedy had managed to cool. They realized too late that the boy had, like so many others, contracted the Spanish flu. The boy of twelve was dead within a week. But the Grim Reaper did not stop there. Two days before the boy breathed his last, his mother felt the beginning of the end stir in her throat. Then it was the father’s turn, and he lasted no more than four days. In all, the flu had plundered four members from a family of only seven, including Madeleine. The Spanish flu had left her an orphan again, depriving her of a father and mother for a second time. Of the three children death had spared, two had already left the family home to get married. The remaining daughter had watched death take the home’s occupants one by one, only to find herself alone. The priest was careful to note in his letter that Clarisse, the unfortunate survivor, was now in the care of the nuns of the state of New Hampshire.

“Are there any of those divine pancakes left?” Father Cousineau inquired. “I think there are indeed!” said Old Ma Madeleine, getting up.

Father Cousineau waited until she was in the kitchen before giving Louis-Benjamin a wink. Between two Americans sobs, the sound of utensils in the kitchen reached them. The priest ruffled the young man’s hair.

“So, my boy. If someone asked you to choose between a trip to France and the American girl, what would you do?”

The boy reddened. He looked down at the wooden table, trying to hold back tears with a weak laugh.

“France is real far!” he said.

“Yes, my boy. Much too far,” the priest replied, taking a sip of tea. “And it’s infested with Germans,” he spat.

“We’re Germans too, Father.”

“I know, but that was before the war, long before. Do you remember Germany?”

“No.”

“Your father neither, nor his father before him. It goes all the way back to the eighteenth century. I don’t think there can be much German left in you.”

“Is the eighteenth century far back?”

“As far away as Germany. And if I were you, I’d keep quiet about it,” he concluded.

Old Ma Madeleine set down a second plate in front of the priest, who didn’t even wait for her to take her hand away before he swiped a piece of pancake, voraciously eyeing a slice of ham glistening in the springtime sun. Outside, the gulls’ cries became more piercing, a few chickadees announced better days, and melted snow ran down the streets, comforting those in mourning. The priest chewed noisily enough for Old Ma Madeleine to consider putting a word in the bishop’s ear the next time he visited. Wasn’t the seminary there to teach good manners? With a nod, the priest signalled for Louis-Benjamin to leave the room so that he could speak in private with Old Ma Madeleine. The youngster leaped up to join Madeleine the American in the kitchen while the priest seized the opportunity to swallow an enormous mouthful of ham.

“There was trouble in Quebec City yesterday,” he announced gravely.

“What sort of trouble?”

“The army is looking for young men to conscript, Mrs. Lamontagne. They sent soldiers from Toronto, English-speaking men who opened fire on an unarmed crowd. Five innocents are dead. It won’t be long until they cross the river and come looking up here. They’ll be after Louis-Benjamin. That good-looking son of yours is eighteen years old.”

Old Ma Madeleine sighed. What could any of this have to do with the drama that had been playing since the priest had arrived?

“The girl no longer has a home to go back to,” the priest said.

“Are you asking me to keep her, Father? She doesn’t understand half of what we tell her.”

“The army doesn’t go around taking fathers from their families, Mrs. Lamontagne.”

There was a silence. Old Ma Madeleine looked outside, where two of her daughters were throwing snowballs at Louis-Benjamin’s brother. It seemed to her that only yesterday her oldest boy had been doing exactly the same thing. She smiled.