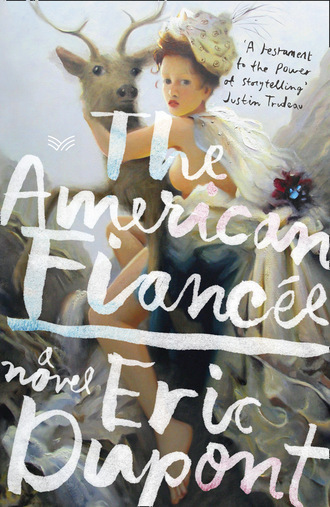

The American Fiancée

“The baby’s facing the wrong way. When was the last time he moved?” she asked the American, who was suffering too much to reply. “This child should have been turned three days ago!” the nun shouted, lubricating her hand with a greasy substance a fellow nun held out to her. “Madeleine, I’m going to have to put my hand inside you to turn the child. It’s not facing the right way at all.”

Sister Mary of the Eucharist slowly put her hand up into the American’s dilated vagina. A flood of amniotic fluid cascaded out onto the straw. A man sitting in the third row fainted. Madeleine screamed blue murder. “Push,” the nun shouted. She removed her hand from deep inside Madeleine, who, her mouth wide open, was now begging to be put out of her misery. From time to time, she would crane her neck to glance down at the nun who was helping her bring her child into the world, only to let out a cry of terror at the sight of her hideous face.

“Try to calm her down!” the nun hissed at the father.

Louis-Benjamin sang into his wife’s ear the only English song he knew: Will you love me all the time? The song did seem to soothe her a little, and there was almost the hint of a smile on her lips. Sister Mary of the Eucharist seemed quite irritated.

“Madeleine, you have to push. Push as hard as you can!”

The congregation held its breath; the little angels sobbed in the pulpit; the women who had given birth themselves felt Madeleine the American’s pain as their own. The men did their best not to rest their eyes on the terrible scene. Madeleine wasn’t making it easy for them: she wouldn’t stop screaming. Suddenly a terrible spasm went through her body and her piercing yell gave way to a thin, reedy sound, a pianissimo con forza howl that shattered Louis-Benjamin’s eardrums. Sister Mary of the Eucharist shook her head. A small, grey arm could now be seen between the American’s legs. The child had chosen this position to be born into the world, but that seemed the least of Sister Mary of the Eucharist’s worries.

“The child has been dead for a while. Now we must try to save the mother.”

Sister Mary of the Eucharist leaped up and ran to the sacristy, where she lived with the other nuns. She reemerged after a minute armed with a peculiar instrument. It looked like a pair of metal pliers, glistening like a jewel in the half-light. The nun ran a determined hand along the little dead arm and pushed her own arm in until she could feel the whole child in its mother’s womb. The maneuver caused a terrible ripping and tearing, and the American began to bleed profusely. The smell of excrement mixed with the scent of the Christmas candles. The nun’s bony fingers found the child’s neck and gripped it firmly. Then, very carefully, with her right hand she picked up the instrument she had brought from the sacristy.

“What is that?” Louis-Benjamin gasped.

“Forceps. We use them to turn and extract babies when they are being born. Madeleine, I’m going to use this instrument to get your baby out. Don’t be afraid. I use them all the time. It’s absolutely normal. Even kings and princesses are delivered using forceps.”

The nun inserted the forceps into Madeleine’s body, found the dead child’s head, and caught hold of it. Then she waited for the next contraction to pull the baby from its mother’s belly.

“Push, Madeleine! Push!”

Resistance was spongy and strong. The baby’s head, spattered with mucus and blood, appeared, lodged between the forceps’ metallic arms. In front of the traumatized onlookers, the nun managed, with a painful grunt, to extract the dead child from the body of its mother who, after arching violently, had fallen onto her back, exhausted from the pain. Madeleine’s wounds continued to bleed horribly, despite the nun’s efforts to contain the hemorrhage. Someone in the congregation began to vomit noisily. The nun looked up at the ceiling, wondering which saint to turn to next. She motioned for Father Cousineau to come forward. She spoke softly into his ear. The priest nodded twice, then knelt down beside the American to give her the last rites. Every gaze followed the same trajectory, tracing a triangle from the dead child, then to Madeleine, before falling inevitably back to Sister Mary of the Eucharist’s sad, frightful face. As soon as it was extracted from its mother’s body, the child was laid on the straw. All eyes were now on the tiny, stiff, greyish-white form, its eyes closed.

“It was a girl,” someone said.

Hands covered in mucus and blood, the nun had her eyes locked on the mother’s open belly, still shaken by contractions. The audience was stunned. Moments before the birth, some had made a break for the jube, clambering up the stairs four at a time to find refuge and escape the gaze of the American and the priest, trying to forget they had ever been witness to the scene. Up above, Louis-Benjamin’s little sisters sobbed in each other’s arms. Two women tried to console them.

“Your brother will have other children. Hush now. Let us pray to the Lord.”

A man stood with his hands over his ears, trying to block out the prayers and the shouting. Of all those the storm had trapped inside the church of Saint-François-Xavier that Christmas night, very few escaped without lasting psychological damage. The parishioners huddled together in the jube tried to strike up a conversation that would have distanced them, in mind if not in body, from this cursed place. But even from up there, any escape from the terrible racket that followed was impossible. After five minutes when nothing but crying, sobbing, and the voices of the obstinate few who persisted with the rosary could be heard, a cry of unprecedented force rang out in the church. The American’s body had started to convulse once again, as the nun held her legs apart. The nun appeared to be no longer aware of anything else around her.

“Jesusmaryandjoseph!” she gasped.

A tiny foot could be seen kicking the American’s still-enormous belly. This one was very much alive, and apparently demanding their attention.

“Madeleine! Madeleine! You need to push! Push harder!”

The American had no strength left. She tried to contract her muscles one last time. The nun plunged her arm back inside her to grab hold of the living child and waited again, patiently, for the last contraction to come. By this point, all life seemed to have abandoned the mother’s body. She was now breathing only feebly to the sound of the prayers mumbled by Father Cousineau. And yet, something in her was still alive: the second child whose existence she had only just learned of.

“Madeleine, push . . .” murmured Louis-Benjamin.

Then Madeleine pushed, slowly and painfully, helped by Sister Mary of the Eucharist, who had a firm grip on the second child’s head. A cry tore through the church. “She’s having another! And this one’s alive!” Every head, which out of respect for the stillborn child had been bowed, suddenly rose again. A drumming of feet could be heard from those who had sought refuge from the horror in the jube and were now racing back down the stairs to see the miracle for themselves. Kneeling on the blood-soaked straw, Sister Mary of the Eucharist, herself dumbfounded at the turn of events, struggled to pull the second child out of the American. From the front rows, people had already seen the child’s huge head emerge, then its shoulders and pelvis, and last of all its tiny feet. Pale pink in color, the baby was already moving its arms, as though to reassure everyone of its health. Sister Mary of the Eucharist patted it on the back a few times, holding it by the feet. A subdued, somber, sinister silence fell over the congregation. The little one’s birth had been a total surprise, but there were already very precise though modest hopes for him: that he let out a cry. They waited another five seconds, then Papa Louis’s voice was heard for the first time, strong, clear, and resonant, immediately followed by one “Thanks be to God” after another, ending the very short period of mourning in memory of his twin sister.

In Louis-Benjamin’s lap, the American showed no signs of life. Her face, glistening in pallor, was even whiter than the statue of the Madonna. An inverse Pietà, the couple was no longer of interest to anyone. Madeleine had passed away in the arms of Louis-Benjamin, who had tenderly closed her eyes. Attention now turned to the child, to the huge baby wailing at the top of its lungs, turning its head right and left like an old man in the throes of a nightmare. “It’s a boy!” Old Ma Madeleine cried from the pew where she was sitting, rosary beads still in hand. Beneath the wooden shelter, Sister Mary of the Eucharist passed the child to his father, whose arms trembled as he reached out. The American’s head fell back against the floor with a dull thud. The nun leaned over and kissed her on the forehead. Before moving away, discreetly, quickly, furtively, she removed the gold chain and little cross that Louis-Benjamin had given her for her birthday on the feast of St. John the Baptist. The piece of jewelry disappeared into the folds of her voluminous habit.

Two or three hours after the child was born, the wind ceased battering Fraserville. Everyone took the opportunity to go home. Madeleine the American and her stillborn child could not be buried right away, so their caskets were stored for the winter at the charnel house. It was only in spring, once the ground had thawed, that mother and baby were buried. Old Ma Madeleine searched high and low for the little cross the deceased had been given as a gift by her husband. But she could not find it anywhere. She asked all those present at the scene, even Sister Mary of the Eucharist, who claimed never to have set eyes on it.

“She should be buried with her little cross,” Old Ma Madeleine sighed in vain.

The Fraserville undertaker engraved Madeleine Lamontagne (The American) on her tombstone, which was solidly planted in the ground that spring at a funeral ceremony Louis-Benjamin did not attend, since on March 1, 1919, one year to the day after Madeleine the American first arrived in Fraserville, his body was found in the Rivière du Loup, at the foot of the waterfall where he had thrown himself to his death, inconsolable, desperate. He was given the burial reserved for those who chose death over life, interred in a small, separate cemetery, far from the mortal remains of Madeleine the American, who, having died of natural causes, had been given a Christian burial. The child was baptized Joseph-Louis-Benjamin Lamontagne on the very day of his birth, but his grandmother, Old Ma Madeleine, always called him Louis, and raised him alongside her remaining five children.

Of the American there remained only a handful of objects: items of clothing, a prayer book, wedding photos, and The New England Cookbook, which the young woman had had in her bags the day she arrived in Fraserville and which Old Ma Madeleine did not have the heart to throw out, and which she could not make out a word of in any case. She packed all the items away in boxes and had her son Napoleon drop them off at the Sisters of the Child Jesus to be given to those in need.

Louis was an unusually robust boy. At birth, he already weighed twelve pounds, a very respectable weight for a boy born in 1918, and a twin to boot. By the time Fraserville had calmed down, by the time Old Ma Madeleine had mourned her daughter-in-law, and then her son, it was spring of 1919, the first year of peacetime after a long war. Father Cousineau had lost the pounds he had put on during the American’s brief stay in Fraserville. Old Ma Madeleine did not really know what she should tell the child. The people of Fraserville would no doubt take care of that for her soon enough. There was always a doubt at the back of her mind; she was suspicious of a boy who was too big and would eat enough for two, already managing to sit up by himself barely a few weeks after he was born. Nonetheless, Old Ma Madeleine had other things to be worried about. One day in June, after the American’s funeral, she insisted on meeting Father Cousineau alone at the presbytery with the child. She wanted, she said, to ask his opinion on a matter concerning the baby. Nothing serious, just a nagging doubt, a question sparked by that sixth sense somewhere between the heart and the mind that serves neither to think nor to love, but that allows a woman to feel rightfully worried.

The priest was only too happy to meet her.

And so Old Ma Madeleine arrived at the presbytery the following day with the child she had difficulty carrying and who was already demanding to be fed even though he had eaten barely twenty minutes earlier. Strangely, the baby stopped bawling as soon as the priest took him in his arms.

“How may I be of assistance, Madeleine?”

By way of reply, Old Ma Madeleine took the child, set him down on the table, and began undressing him. Once he was wearing nothing more than a cotton diaper and babbling ga-ga-gaa, the priest repeated his question.

“The child seems perfectly normal to me,” he added. “A little hefty for such a young thing, but when you think of so many other children being born all sickly and skinny, it’s nice to see one so robust! He’ll be a strong man, your Louis!”

The priest gently pinched the child’s plump thighs between his thumb and index finger as Louis smiled, revealing what looked like a tooth on its way. Old Ma Madeleine sighed and undressed the child completely to show him to Father Cousineau as God intended. She pointed between little Louis’s legs. Father Cousineau squinted, then put on his spectacles, because he was rather far-sighted. His jaw dropped. There was a moment of silence, then he looked Old Ma Madeleine in the eye and muttered: “May God preserve it for him!”

In the living room on Rue Saint-François-Xavier, Papa Louis’s impression of Father Cousineau had the children rolling about laughing.

“And then in 1919, Fraserville became Rivière-du-Loup,” he went on. “Officially, I’m as old as our town! You children should know that!” he said, finishing his fourth gin of the evening.

In the meantime, Madeleine and Marc had undressed their brother Luc. He was already sound asleep. He barely made a sound when his sister Madeleine slipped his undershirt off. Then they pulled their pants down and inspected each other. Madeleine buried her face in her hands in shame.

“Papa Louis! I don’t have one!” Marc lamented.

“Not all three of you have one,” Papa Louis responded. “Only your sister and your little brother.”

They all gathered around Luc first, still asleep on the sofa. An inch above his ankle, he had a small birthmark about the size of a dime and shaped somewhat like a bass clef.

“What is it?” he asked, waking at last.

“A bass clef,” replied Papa Louis. “It’s for writing music on staves.”

The children looked at it, wide eyed. In their excitement they hadn’t heard their mother Irene return home from the convent. This was how she found them, bedtime long since passed, Papa Louis tipsy, Luc stark naked, Madeleine and Marc with their pants down. Too late, they turned to see her, standing fuming at the living-room door. If it is possible to describe such an expression in words, it could be said Irene had the end of the world written all over her face. In a flash, she grabbed her pantsless son by the scruff of the neck and marched him upstairs to his bedroom. Without a word—just a look—she picked up Luc and ordered Madeleine up the stairs, where she closed the door to her daughter’s bedroom and told her in no uncertain terms to go to sleep.

“We’ll talk about all this tomorrow.”

In a dream, half awake, little Madeleine could hear her mother’s shouts rising from the living room. The glass thrown against the wall shattering into pieces. A “Christ Almighty!” from Papa Louis. The dull thud of a woman’s body flung against a wooden floor. Once. Twice. Then silence. The sound of water running. In the parlor, Sirois’s body went on decaying to general indifference.

The dead mind their own business.

A Black Eye is Watching You

YEARS BEFORE A journalist dubbed her the “Queen of Breakfast” at the opening of one of her restaurants in a Toronto suburb, Madeleine had been a little girl almost like any other. Lots of people could have told you that, people like Siegfried Zucker, a kind of door-to-door salesman who once a month traveled the length and breadth of the Lower St. Lawrence in a truck chock-full of foodstuffs that he hawked at knock-down prices that could be knocked down even further if you were ready to bargain. Zucker, an Austrian who came to Canada after the war, had decided to make the Lamontagne home the last stop of the day. He was always welcomed by Irene Caron, a hardened negotiator, and her little girl, Madeleine. It was probably the Austrian who first picked up on Madeleine’s nose for business. When she was eight, Zucker once offered Madeleine a barley sugar lollipop in the shape of a maple leaf. They were standing outside on the steps while her mother carried what she’d bought into the kitchen.

“Can I have one for my brother Marc?”

“Why of course!” Zucker replied, handing over a second candy.

When Zucker came to deliver Irene Caron’s order the following month, there was no sign of little Madeleine. Instead, he found her brother Marc playing on the porch with a cat. The boy thanked him for the previous month’s lollipop.

“At that price, you’re practically giving them away!” he laughed to Zucker, who realized that Madeleine had sold the candy to her brother.

Far from being shocked, Zucker developed an instant fondness for Madeleine. In some ways, she became his favorite customer. He would often haggle with her over imaginary wares, testing the child’s perspicacity, and she never let him down. Madeleine in turn grew fond of the man she came to associate with abundance, profit, and barley sugar.

Aside from Zucker, no one in the parish of Saint-François-Xavier could ever have imagined that the undertaker’s daughter would one day turn the restaurant world on its head, revolutionizing how North Americans defined breakfast. Madeleine seemed predisposed to nothing but the ordinary, tedious, and laborious life of any French-Canadian woman. But from the moment she entered the convent school, the nuns discovered she had a gift for mental arithmetic. As it happened, her brothers had been the first to realize her talent the day all three of them had been watching The Horse do a bench press and Marc had wondered out loud how much the barbell weighed.

“How much do you think, Madeleine?”

In a split second, Madeleine had, to her brother’s astonishment, added and multiplied the round weights plus the bar.

“Two hundred and thirty-five pounds.”

Then, at the age of eight, she had, without really meaning to and in the offhand way that only little girls can manage, surprised an entire grieving family with her math skills. It was at the wake of the widow, April. Madeleine, holding a tray of cookies, was following her mother about while she poured coffee into the cups of the family come to keep vigil over the wrinkled corpse of the old woman whose niece had found her sitting dead in her rocking chair. The niece, a woman in her thirties whom grief had made voluble to a fault, chattered incessantly while the other relatives, absorbed by their rosary, seemed oblivious to her.

“It’s strange just to go like that. She wasn’t even ill. Of course, considering her age . . . How old was Aunt Jeanne anyway? Let’s see, she was three years younger than her husband and he was born in 1891, so that would make her, uh . . .”

“Sixty-four,” Madeleine piped up, as she proffered the tray of cookies, instantly reducing the woman to silence, much to the relief of the rest of the family.

Besides this gift for numbers and the effect the stories of Louis “The Horse” Lamontagne—a man she considered a demigod—had on her, Madeleine had only one other exceptional character trait: she had a jealous streak, a poison she had begun imbibing without reserve the day the letter from Potsdam, New York, arrived. In theory, the letter from Potsdam should never have fallen into Madeleine’s hands, but fate had decided otherwise. On that particular day in September 1958, Irene had kept her daughter home so that she could catch chicken pox from her little brother Marc, who had caught it at the boys’ school.

“Better to have it at her age than once she’s an adult. It’ll be over and done with.”

Irene tucked the still-sleeping Madeleine into the bed of her crying brother, whose hands Papa Louis had tied behind his back to keep him from scratching himself raw. There he was, trussed up like a turkey and itching all over, when his sister arrived in his bed. Irene had to go out for a few minutes and Louis had left to pick up a corpse from a house on Rue Saint-Pierre. Which meant that the children were all by themselves when the letter dropped into the letterbox on Rue Saint-François-Xavier. Madeleine heard the metal click and the postman’s footsteps on the wooden porch. Curious, she went downstairs, ignoring Marc’s pleas.

“Scratch me or untie me, will you!”

The envelope with the red and blue border caught her attention. It bore an American stamp with an old man on it. And the address, which wasn’t easy to read for a youngster of eight:

Louis “The Horse” Lamontagne

Rivière-du-Loup

Province of Quebec, Canada

The sender, a lady by the name of Floria Ironstone, had written the return address on the back of the envelope. Potsdam, New York. Madeleine read the name one syllable at a time, stumbling when she got to the impossible-to-pronounce Ironstone. She took an instant dislike to the name Floria. This person—she could feel it—wanted to steal her Horse away from her. She immediately sensed the letter was a threat to her happiness and decided then and there that it would never reach its intended recipient. Seeing her mother at the end of the road, she scampered up the stairs, holding her booty at arm’s length. She barely had time to hide the letter behind a baseboard and race back to her brother’s room (where poor Marc was being driven mad by the itching) before Irene opened the door downstairs. Apart from this letter from America that she had intercepted in the nick of time, Madeleine used to hide all kinds of valued finds behind that board, little treasures she had “discovered” here and there, and that glinted and gleamed. Sometimes at night she would pry back the board, the door to her secret safe, to admire her fortune by the light of a polished-glass lamp. And this is what she would see there, shining in the magpie’s dusty nest:

—a wedding band stripped from a dead man’s hand at a boisterous wake where the grieving relatives had decided, just before closing the casket for the last time, to settle a few old scores over fisticuffs on Louis Lamontagne’s lawn. While Papa Louis separated the men, Madeleine had snuck up to the casket and pocketed the shiny ring that had been calling out to her with every ray it had for the past two days;

—a silver spoon given to her brother Luc and every other child in the Commonwealth who had been born on June 2, 1953, to commemorate the coronation of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II;

—and a cheap flower-shaped earring her brother Marc had found in the mud in the spring of 1957.

Irene was upstairs now.

Madeleine pushed the board back in place.

“Put that on your brother’s spots, Madeleine. It’s calamine lotion, it’ll help.”

Madeleine made a face. Marc begged his mother to untie him.

“It itches so bad!”

“It’s perfectly normal. It’ll pass.”

Ten days later, it was Madeleine’s turn to be smeared in pink calamine lotion, her wrists tied tight behind her back.

“It’s for your own good.”

Now, you may well wonder why Madeleine refused to open Floria Ironstone’s letter. The explanation is quite simple. She was convinced that its contents, for as long as they remained imprisoned inside the envelope, wouldn’t be able to disrupt things. To the little girl’s mind, a letter is only a letter once it has been opened. By opening the envelope, she risked setting free a virus that she knew would prove fatal to The Horse.