Полная версия

Claves del derecho de redes empresariales

From this perspective not only the first assumption (against network financing) but also the second (against contractual network financing) should be revisited. The advantages of a contractual setting for self-financing in networks could be valued.

As seen above, the multi-party contract could also oblige participants to financially contribute to the common project through the formation of “special purpose funds”. “Peer to peer” forms of internal monitoring could help to enforce such a commitment. Enforcement of contribution duties could be ensured through a more formalized assignment of monitoring powers to internal bodies in charge of controlling payments and sanctioning any possible breach. Indeed, the use of internal governance and monitoring mechanisms is compatible with mere contractual schemes and is becoming more and more common in collaboration contracts238. The Italian experience of network contracts shows that a participant’s exclusion from the network for lack of financial contribution is a very common sanction as provided by the contracts239.

The role of the network contract as a means to improve the efficiency of asset allocation among different projects should also be emphasized, though the practice is still quite poor in this respect: internal auctions or other comparative procedures as well as pre-defined processes for possible renegotiation and reallocation of resources among the projects at stake could be provided by the contract design, so limiting discretion of network managers and directors under these respects.

In the specific perspective of contribution duties, mere contractual networks could even show higher flexibility than organizational networks, especially if the law of corporations is taken into account. Indeed, once the corporate capital legislation is considered, limitations might be provided by the law as to individual financial contributions to the company240.

Conversely, the law of organizations (and corporate law in particular) shows higher potential with regard to a different type of rule that has been mentioned above, concerning the asset lock over special purpose funds241. Once financial contributions are pooled together, the effective use of these resources for the accomplishment of the common interest project depends on the level of fund partitioning, as allowed by the applicable law. As seen above, although differences exist among domestic legal systems, organizational law normally ensures both affirmative and defensive asset partitioning to a larger extent than contract law: preventing participants from diverting the pooled resources from their destination; preventing their individual creditors from seizing these goods; assigning seizing powers only to the creditors whose rights are connected with the fund’s purpose242. The possibility of attaining similar effects when the network is merely contractual depends on domestic legislation but is generally limited.

In a different way other types of “lock” on the network assets could be established on a contractual basis. Depending on applicable law, these measures might be enforceable among parties only, without being opposable against third parties. For example, parties could limit for a certain time the dissolution of joint property or could limit the participant’s right to recover his/her contribution in case of a withdrawal or exclusion, as is the case in many network contracts in the recent Italian experience.

6. CONTRACTUAL NETWORKS AND ACCESS TO BANK FINANCING

The previous analysis demonstrates a critical view on bank financing of inter-firm network projects. In fact, moving from the European legislation on credit institutions, the interdependence among network participants’ assets and activities represents a source of concern and higher risk of credit more than an element enhancing the economic perspectives of the financed project. The banks’ persistent focus on the applicant’s assets and guaranties more than on the characteristics of the project due to be financed, seems to currently reduce, rather than increase, opportunities for networks’ financing, especially in case of mere contractual networks.

Some banks interested in network projects financing are currently exploring a different view. This interest is being significantly stimulated by the new legislation on network contracts in Italy, as presented above.

More particularly, these banks are considering the possibility of adopting specific standards for a network’s rating within the “Internal Ratings Based Approach”243. Such an approach would imply a higher focus on the qualitative aspects of the project due to be financed, though in addition to ordinary quantitative measures normally used to assess credit merit. In this perspective banks would start to consider that “high quality networks” may improve participants’ financial rating and, consequently, credit conditions.

What could a “high quality network” be, however? Could a mere contractual network ever qualify as “high standard”?

Pursuant to one of the schemes proposed by a European bank to evaluate the credit merit of networks’ participants, the following elements, as provided by the network contract, would positively influence this evaluation: (i) the medium-long term of the project, consistently with the business plan; (ii) the general definition of the objectives; (iii) the general determination of the operational program; (iv) the specific determination of rules concerning relations among participants, consistently with the operational program; (v) the governance rules, including internal and external control; (vi) the accounting rules; (vii) the asset/contributions pooling, common fund, if consistent with the operational program; (viii) the asset safeguard and protection measures244.

This evaluation scheme would subscribe to the hypothesis according to which contractual design and internal governance of a partnership can reinforce trust in the relation between partners and third parties, including financiers. The quality of collaboration can indeed influence the parties’ capabilities to effectively accomplish the envisioned project, eventually increasing the common assets’ value and/or raising sufficient revenues to return capital and pay interests. For example, another very significant aspect is represented by the rules concerning entry and exit in the network contract, themselves influencing the stability of the business collaboration together with the feasibility of the network programme245. An adequate contractual network design could then help to align the financier’s and borrowers’ incentives to “invest” in the network project. Which type of contractual design and which governance rules would better pursue this scope is an issue that deserves further analysis and investigation, also at a practical level.

Additionally, law and economic literature also suggests that affirmative and defensive asset partitioning is due to enhance a firm’s ability to access (bank) credit246. Under this perspective, although the conventional tool to attain such partitioning is still the incorporation of the (firm or) network into an entity that is distinct from the one of each person participating into the (firm or) network, legal systems are evolving towards more flexible schemes of asset partitioning that do not require any establishment as an entity. After the latest development the case of the Italian network contract has followed this path. To what extent this model may be replicated in other contexts and legal systems depends on legal traditions and applicable domestic law247.

7. CONCLUDING REMARKS

Within the current economic crisis, networks may not represent a panacea, nor a sheet-anchor for enterprises in distress. They may however provide opportunities for enterprises willing to collaborate for the accomplishment of strategic programs direct to improve their innovation capability and competitiveness.

Among other obstacles, the difficulties in financing collaboration programs risk to undermine such opportunities, inducing enterprises to persist in their monadic approach to market.

A shift from personal financing to project financing is envisioned, so that the plurality of actors involved in the accomplishment of a project becomes a source of value rather than a mere lever for transaction costs in financial contracts.

Of course, this change cannot take place at the financial and credit market’s expenses through a shift of risk towards financiers. Such a change would be unrealistic at the present conditions.

Not only could networks develop internal financing strategies taking advantages of economy of scale and sharing already available resources within the network, but also external financing could be promoted through an adequate contractual design able to reinforce potential financiers’ trust through the establishment of internal monitoring structures, auditing procedures, accountancy rules, cross-guaranty mechanisms, reserve funds and the like.

The mere contractual form of a network would not represent an obstacle as such under these approaches, provided that the legislation was clear in defining the general legal framework in which inter-firm collaboration contracts could be drafted and, particularly, as far as financing is concerned, liability regimes should be determined in terms of both contractual liability and asset liability (responsabilità patrimoniale) as specifically regards asset partitioning effects.

The recent Italian experience of legislation on network contracts shows some potential in terms of contractual design and, at least partially and at a former level, in terms of a bank’s availability to engage in a process of experimental evaluation of credit merit within a network. More can be done in terms of development of planning and accounting rules to be applied to network activities and economic interaction among participants.

The European echo of this debate is still hard to perceive. European industrial policies are paying increasing attention to inter-firm networks248. By contrast, the present debate on European Contract Law is not yet adequately considering the importance of longterm, collaboration and network contracts249. As a result, some scholars are envisioning a path towards the definition of general principles on inter-firm networks as well as the study of model contracts250. What role, rights and duties should be reserved to financiers within these models? Should general principles state requirements and conditions under which networks can enjoy some level of asset partitioning and limited liability? To what extent would European intervention with regard to inter-firm networks induce any change in the Basel Accords approach towards risk concentration? Is there any room for a pro-active (rather than defensive) approach to networks in the international debate on merit credit standards? These are among the questions to which networks’ financing theory would still need to provide answers.

CAPÍTULO 5

Cooperation and Competition Dynamics of Business Networks: Strategic Management Perspective

SASCHA ALBERS

1. INTRODUCTION

Strategic management is concerned with explaining superior firm performance. Researchers in this field try to find sources of (sustained) competitive advantage vis-à-vis other firms, and suggest that firms that have a competitive advantage outperform their competitors (Barney & Arikan, 2001; Powell, 2001). Various sources of competitive advantage have been identified, and represent the capstones of the dominant strategy theories: A firm’s distinct resource endowment (Barney, 1991), capabilities (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997), method of interacting with rivals (Chen & Miller, 2012), and positioning in its industry (Porter, 2008). Additionally, a firm’s design of single relationships with other firms (for example, its suppliers, distribution channels, but also competitors), as well as the configuration, management and development of its overall relationships with other organizations, have together been identified as source of competitive advantage (Dyer & Singh, 1998). These inter-firm relations are usually discussed under such labels as (strategic) alliances, joint ventures, or networks (Cropper, Ebers, Huxham & Smith Ring, 2008). The creation, maintenance, adaptation and termination of cooperative relationships are complex tasks that have earned the interest and attention of numerous managers and scholars alike.

2. BUSINESS NETWORKS AND STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT

Business networks are a specific manifestation of inter-organizational relations. They consist of multiple members and are purposefully formed. In management and organization theory, they are also labeled alliance networks (Koka & Prescott, 2008), multilateral alliances (Kleymann, 2005), alliance constellations (Gomes-Casseres, 2003) or alliance blocks (Vanhaverbeke & Noorderhaven, 2001). Business networks have spread over the last years across a variety of industries, and their strategic effectiveness— that is, their means of achieving and sustaining competitive advantage — is undisputed.

Scholars have acknowledged the role of various industry contexts that influence the design of networks in competitive interaction (Lazzarini, 2007; Vanhaverbeke & Noorderhaven, 2002). They have even observed some network-intensive industries where competition is said to take place among cooperating sets of firms rather than individual firms (Gomes-Casseres, 1994; Nohria& García-Pont, 1991; Silverman and Baum, 2002). The automobile, biotechnology, mainframe, and airline industries have all been described as being, “polarize(d) into competing alliance constellations” (Gimeno, 2004: 821).

However, alliances and networks as cooperative relationships are inherently unstable (Das &Teng, 2000): studies regularly report failure rates of more than 50 percent (Park &Ungson, 2001). In contexts and situations where network membership is essential for firms’ economic performance, the network’s fitness and survival are major member concerns. Exits or member failures can result in troublesome repercussions for remaining partners. Especially in highly specialized networks with only a few large-sized members, the exit of one firm can lead to serious gaps in the remaining members’ service portfolio, potentially leading, in turn, to the failure of the whole network. For example, in the global airline industry, Star Alliance suffered from failures of members Ansett Australia (bankruptcy in 2001) and Varig (ceased operations in 2007), which resulted in substantial white spots on the Star route network. The remaining members from the United States, Europe, Africa and Asia were hindered in their ability to offer seamless connections to and from Oceania and South America, putting them at a competitive disadvantage. Mergers and acquisitions also impact members of competing networks. For example, LAN from Oneworld acquired TAM, a Star Alliance member, in 2012, and subsequently announced that the merged company, Latam, will turn to Oneworld for both of its airline brands. As Latam’s chief executive explained, “We evaluated all possibilities and we chose Oneworld, because it is the alliance that offers the best benefits, connections and products for our passengers, as well as better synergies for the Latam group” (as cited in Pearson, 2013).

For this reason, network members have an interest in establishing stable yet adaptable network structures as well as in attracting and keeping the “right” members in their ranks.

3. BUSINESS NETWORK DYNAMICS

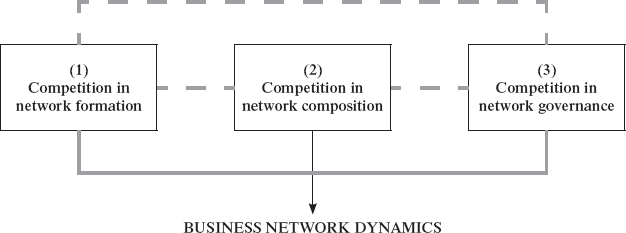

Business networks are cooperative entities formed by more than two firms in order to generate competitive advantages for each member. However not all business networks are alike: they vary with regard to their purpose, structure, size, effectiveness and efficiency. In many industries, firms can join alternative networks, and will select whichever brings the greatest advantage, as the Latam example illustrates. Cooperative entities are thus faced with specific forms of network competition as a main driver of network dynamics (see figure 1):

First, business networks can be challenged in their purposeby other competing networks (competition in network formation). Such competing networks might be substitutes with regard to their raison d’être and the function they serve for their members. Firms may consider the membership in their present network (incumbent network) as obsolete or less advantageous, project higher benefits (of whatever kind, e.g. financial benefits or higher status) to their membership in the newcomer network, and can decide to switch from one to the other. If many member firms decide to follow this logic, incumbent networks that are unable to match the benefits of competing networks, or have lost sight of their specific advantage for their members, will degenerate. On the other hand, this type of competition gives rise to innovative networks that provide timely and relevant benefits to their members and do not lose sight of their purpose.

Second, networks compete for growth and stability in their member constellation (competition in network composition). They attempt to attractnew members, but also to retain existing members. To do so, networks need to employ processes and tactics that produce more or unique member advantages. This relates to network competition with regard to membership structure.

Third, networks compete in achieving and maintaining an effective and efficient administrative structure (competition in network governance): The most effectively organized network can generate more benefits for its members than other networks, or it can generate similar benefits than other networks faster, at lower costs, or with greater frequency or reliability. In order to devise the most effective governance for a network, questions of decision-making mode, organizational structures and processes need to be addressed.

FIGURE 1: Three forms of network competition as drivers of network dynamics

In the remainder of this chapter, I will further elaborate on each of these network competition forms, present one exemplary research study for each and suggest implications for network and corporate management.

3.1. Competition in Network Formation

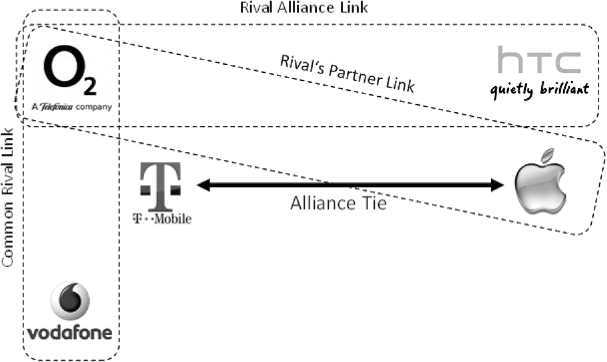

Competition in network formation occurs when a firm (or a group of firms) discovers an opportunity to realize a relevant benefit or advantage that can most effectively be exploited by cooperating with others. In this case, competitors will ponder whether they are brought into a disadvantageous situation and consider a potential reaction. Of course, a firm will strive to compensate any potential disadvantage brought about by a rival. Network formation as a competitive move has only slowly gained research attention (Silverman & Baum, 2002). Gimeno (2004) analyzed alliance formation dynamics between competitors; that is, how firms respond to their rivals’ alliance strategies. He suggested that firms react by either trying to ally with the same partner that the rival has formed cooperative ties with, or building a countervailing alliance with different partners that provide similar benefits (see figure 1).An example is T-Mobile’s exclusive 2007 distribution agreement for Apple’s fashionable iPhone in Germany, a move that put the firm’s competitors at a major disadvantage. T-Mobile’s rivals (for example, Telefonica’s O2, or Vodafone) were faced with two options:

FIGURE 2: Illustration of Reaction-Types in Alliance Formation

Source: adapted from Gimeno (2004)

First, try to neutralize T-Mobiles’s advantage by imitating its move and form an alliance with Apple that would challenge T-Mobile’s exclusivity (a “rival’s partner link” in Gimeno’s terminology). This would depend on the exclusivity clause in the T-Mobile-Apple agreement, but also on T-Mobile’s bargaining power. Since Apple intentionally foregoes additional revenues and efficiency potentials in exploiting its resources by restricting its customer base to those of a single network, T-Mobile will have to pay an exclusivity premium. Depending on the size and bargaining power of T-Mobile and its competitors, however, the exclusivity premium and clause will be more or less enduring and strict.

Second, T-Mobile’s rivals could establish countervailing alliances. Within this option, two further possibilities exist: forming an alliance with one of Apple’s competitors, ideally a close substitute, such as Samsung or HTC (Gimeno’s “rival alliance link”) in order to address similar consumer desires by different technologies, and thereby reduce the (potential) drain of own customers that turn to T-Mobile due to the iPhone offer. Or T-Mobile’s competitors could form an alliance among themselves, e.g. O2 could ally with Vodafone (Gimeno’s “common rival link”) and attempt to jointly attack T-Mobile on different features of its offers. This countermove could then address an element in T-Mobile’s product and service portfolio totally unrelated to smartphones and expose a weak spot in its competitive posture, a phenomenon known from multi-market contact theory (Yu & Cannella, 2013).

Gimeno (2004) suggested that partner selection and the type of alliance formed as a response to a competitor do not follow a naïve logic; that is, neither allying with a rival’s partner nor the formation of countervailing alliances is systematically preferred. Rather, alliance type choice depends on the degree of co-specialization, which itself reflects the degree to which alliance partners emphasize the specific needs of the particular partner, inter alia through specific investments, or by providing proprietary knowledge. In our example, if Apple offered a specific version of the iPhone in the shape of a T-Mobile logo, and T-Mobile installed specific T-Mobile-iPhone stores, this would reflect relationship-specific investments into the alliance that would be lost if the alliance broke up. Gimeno is thus able to show that rivals’ co-specialized alliances may involve exclusivity, precluding alliances with rivals’ partners and thus encouraging countervailing alliances.

Overall, a firm’s network formation, or its joining an existing network, can lead to manifold competitor responses. From a strategic management perspective, this implies at least three imperatives:

First, firms need to make sure that they are aware of competitors’ partnering actions as an essential part of competitor analysis (Gnyawali & Madhavan, 2001).

Second, firms need to implement and improve the capability to assess the consequences of competitor actions in alliancing and quickly generate potential responses. The options that Gimeno (2004) provided are certainly neither exclusive nor exhaustive, but might serve as a first framework to devise possible reaction strategies.

Third, taking a proactive approach to the opportunities generated by alliance formation can lead to a temporary advantage: Firms could therefore actively seek opportunities in order to improve their own positions via alliances, and consider that first-mover advantages may offer substantial returns, at least in some environments (Suarez & Lanzolla, 2007).

3.2. Competition in Network Composition

The competition for «good ideas», that is, identifying sources of beneficial cooperation that could otherwise not be realized, is only one dynamic that challenges firms and existing networks. Once established, networks will discover the potential — and, over time, even the imperative — to improve their setup, including their organizational structure and management (to be dealt with in the subsequent section of this chapter), as well as their member base.

The specific member constellation (network composition) with its idiosyncratic resource and capability endowment determines whether networks can deliver on their intended benefits. Therefore, to improve their resource and capability base, they often proactively search for new members. However, in most industries, strategically relevant resources are owned by a limited number of firms (Gomes-Casseres, 1996) and networks often compete for identical partners in order to secure or increase their share of the industry’s available rent (Uzzi, 1997; Gomes-Casseres, 2003). As a result, the fastest-moving network gets the most appropriate members, thereby improving its competitive position (Gomes-Casseres, 1994; Silverman & Baum, 2002). The urge to acquire new members is especially great if rival networks enlarge rapidly (Gomes-Casseres, 1994). Along with the growth of rival networks the pool of desirable members shrinks, provoking membership competition for appropriate partners (Möllering, 2010; Silverman & Baum, 2002). Due to the existence of dual membership and the usually fluid nature of network contracts, competition exceeds the remaining pool of available partners in the industry and also affects existing memberships (Möllering, 2010). Thus, networks need to deploy sufficient retention efforts, since the loss of a core member potentially reduces the network's viability (Gomes-Casseres, 1994). In the airline industry, for example, Austrian Airlines was a founding member of Swissair’s Qualiflyer Alliance that was formed in 1992. However, in 2000, Austrian changed to the Star Alliance, which contributed to the demise of Qualiflyer and eventually to Swissair’s 2002 collapse.