Полная версия

When I Had a Little Sister

One way or another there seemed to be a lot of death about as we grew up – Old Jack, Great-Great-Aunt Alice, Grandad, endless farm cats, sickly piglets and occasional calves born dead, which is possibly why I was obsessed with ghost stories – tales of people coming back, people who were dead but not truly gone. I read and reread Aidan Chambers’s Ghost Stories and More Ghost Stories and, when all else failed, my Sunday-school prize, Saints by Request.

One afternoon Wuthering Heights came on the television. Mum said, ‘You might like this, it’s a ghost story.’ I watched, enraptured by Merle Oberon and Laurence Olivier. The following day Mum went specially to John Menzies in Preston and bought me the book. I was ten years old and sat on the hearthrug doggedly reading it although I did not understand many words and had to skip Joseph and his broad Yorkshire dialect altogether (even though Joseph was basically Gran). Over several evenings I immersed myself in the passion and the brutality, the obsessive revenge, the jealousy and the violence of a story about a girl called Cathy that took place largely in a Northern kitchen. Mum recalled me finishing the book, turning to the front, reading the introduction, asking ‘What’s incest?’ (pronounced in-kest), getting no answer and starting the book again. This was a wild world where life and death were close to each other; where it was better to commune with somebody even if they were dead than not commune with them at all.

Elizabeth, Tricia and I attended a Church of England primary school and we regularly went to Sunday school at the village church. Sunday school mainly consisted of Mr Herbert, the vicar (or ‘parson’ as my father called him), reminiscing about being bombed in Coventry during the Second World War and did not seem to have much to do with God – or at least did not address the interesting questions like did God really look like Old Jack and where, exactly, was heaven.

As a child I did not think to question the existence of God and took comfort in both the idea of a Gentle Jesus Meek and Mild Looking Upon this Little Child, and the vague notion of a heaven – which, I supposed, hovered somewhere or other full of all the dead people and animals I had ever known. At Christmas, God and Father Christmas became rolled into one – a jolly-faced old man who knew exactly what you’d been up to. The Father Christmas version of God was more worrying than normal-God because he could punish you by failing to bring the selection boxes, talc and bath-cube sets and embroidered hankies that appeared under the tree every year.

My Aunty Dorothy gave me a white King James Bible when I was confirmed aged ten which contained photographs of the Holy Land; of barren rocks, entitled In the Wilderness, and silhouettes in a boat upon sparkling water, called Fishermen on the Sea of Galilee – photographs I half-believed were taken in the time of Jesus Christ himself. There was also a ‘Births, Deaths and Marriages’ section for me to fill in. I was proud of my Bible and found it considerably more interesting than the Book of Common Prayer I received at the same time. I noticed there was a chapter in the Bible that was never mentioned at school or Sunday school – the Revelation of St John the Divine. I wondered if perhaps the vicar didn’t want to jump ahead and spoil the end of the story.

I asked my mother what it was like when we were dead. She said, ‘Ask Mr Herbert.’ Mr Herbert had white hair that stood on end and waved like a dandelion clock, he wore thick black-rimmed glasses and a dog collar and his hands shook. I once met him on the way back from a trip to the grocer’s. He was carrying a wicker basket in which a lone half-sized tin of spaghetti hoops in tomato sauce rolled forlornly back and forth.

Mr Herbert came to school every Friday to tell us a story from the Bible but he did not engage in casual conversation with the pupils so I did not feel able to ask him anything. Instead I made up my own idea of heaven and decided heaven was a party in the village hall. I pictured the wooden chairs lined up around the edge of the dance floor, George the disc jockey getting his records ready, unseen ladies in the kitchen cutting sandwiches, arranging slices of Battenberg cake and over-diluting orange juice, the coloured lights glowing and the disco ball throwing sparkles hither and thither as it gently rotated – just like before the annual children’s WI Christmas party, in fact. But, this being heaven, it was a party only for the dead. Early doors Old Jack was there by himself but by the end of the 1970s all the empty spaces on the ‘Deaths’ page in my Bible were complete and the party was in full swing.

One night lying in bed in our freezing bedroom I asked Elizabeth whereabouts in the sky this heaven might be and she said, ‘Guess.’ I pointed up into the blackness somewhere over the milking parlour. ‘Nope,’ she said, pointing over the back garden towards the hen cabins, ‘other way! I win! That means you’ve got to get out of bed to put the light out!’

As a child there were a lot of people in my world and many of them were old.

I remember the moment I realized not everyone lived a life like mine, not everyone lived on a farm or even in a village. I was three or four years old and standing on the pavement in the local town waiting for the Whit Monday parade. Crowds two or three deep waited for the marching bands, the floats covered in crêpe paper and the festival queens with their retinues from all the surrounding villages – but I faced away from the road and stared at the toy-town houses behind me. I could tell they were tiny even though my head barely reached the door handles.

These houses were not like farmhouses; their front doors opened onto a pavement not a garden path or a farmyard, they had windowsills that I – somebody who didn’t even live there – could sit on, and they had windowpanes that I could press my forehead against and see right through. I stared harder. Yes, I could definitely see somebody’s ornaments and their settee and their fireplace.

Everybody I knew lived on a farm, usually down a long lane, surrounded by fields and woods and ponds and a yard and a garden and an orchard. Nobody could sit on our windowsills or look through our windows at our ornaments or our settees or our fireplaces.

‘Turn round,’ my mother said. I didn’t. I kept staring. Were these houses for old people, people who couldn’t walk and who sat in armchairs all day, like Old Jack? They couldn’t be for children, surely; not children like me and my sisters and my gaggle of cousins who could run as hard as we liked for as long as we liked and still not reach the neighbours.

I couldn’t believe how unlucky other children were not to have their own farms. All my relations had farms and each family was known by the name of their farm: ‘Sharples are here!’ ‘Crookhey have landed up!’

Each farm was popular for a different reason. ‘Sharples’ had a wood, ‘Crookhey’ had a pony, ‘High House’ had a brook, ‘Hookcliffe’ had a mountain, ‘Throstle Nest’ had a grassed-over gravel pit, ‘New House’ (us) had a great stone barn with the world’s best rope swing and an old hen cabin filled with discarded furniture – tables and chairs riddled with woodworm, cupboards with warped doors that wouldn’t open and then wouldn’t shut again, an old camp bed with creaky springs, and everything coated in dust – which was the best den in the world. Farms were chock-a-block with hiding places and climbing trees and animals and it was easy to escape the adults while you created whatever world you wanted, but the people who lived in these houses, these tiny houses right beside the pavement, apparently all sat together in cramped little spaces, with strangers staring at them through the window.

Despite having so many cousins, my sisters and I were thrown together a lot without the company of other children. I knew I was lucky to have Tricia from very early on.

I was maybe six years old. It was dinner-time (the meal we ate at midday). We had set places at the kitchen table: Dad at the head, me and Tricia with our backs to the lumpy Artex wall, Elizabeth and Mum with their backs to the kitchen fire, Mum near the cooker, and Gran at the bottom. On this day I was upset and left the table – did I ask for permission? I don’t remember – but asking for permission was considered important in our family. Please may I leave the table? Table manners were some of the few rules I remember my parents explicitly teaching us – presumably so other people would think we’d been brought up right.

Don’t put your elbows on the table; Don’t talk with your mouth full; Always put your knife and fork together when you have finished; Never lean in front of other people; Don’t scrape your knife on your plate; God forbid don’t lick your knife; Don’t say ‘God Forbid’; and always chew with your mouth closed.

I was once sent away from the table for laughing.

I can’t remember what upset me on this particular day but I left my place and curled into a ball on the living-room carpet, forehead pressed to knees, crying. I heard Mum and Dad laugh and I looked up. Next to me Tricia – only a toddler at the time – had curled into an identical ball to keep me company. I sat up, my face wet and cold with tears and with bits of dust stuck to it from the carpet. Tricia sat up too and looked at me with her solemn brown eyes. I of course did not know the word ‘empathy’ but I thought: Tricia is here. Tricia is with me. Tricia understands. Tricia is the one who loves me.

Tricia was the most loving and lovable child, so sweet-natured it was easy to take advantage of her. She was cooperative and eager to please – not in a needy way but in a happy way.

Elizabeth and I were good at giving her orders: get this, get that, fetch this, fetch that, go for this, go for that, play this, play that, watch this, watch that. I made her play ‘Schools’ before she knew what a school was and had no idea about bells and desks and lessons, and stared at me baffled as I kept ringing an imaginary bell in her face expecting her to line up for playtime. I made her play ‘Hospitals’ when she was small enough to be crammed into the dolls’ cot and be fed ‘medicine’ of sugar and water. She wasn’t keen on the sugar and water but she wanted to play so much she went along with it. Tricia was always game – we’d realized that when she suddenly stood up and walked at nine months old.

Inevitably, as two’s company and three’s a crowd, Elizabeth and I fought over Tricia and, with me being younger than Elizabeth, I often lost. When all three of us played ‘Houses’ in the old hen cabin, Elizabeth was ‘mother’ in the best cabin with all the best junk furniture and Tricia was her baby while I got to live in the rubbish cabin (the cabin next door filled with logs and chicken wire) and be the nasty neighbour, Mrs Crab-Apple.

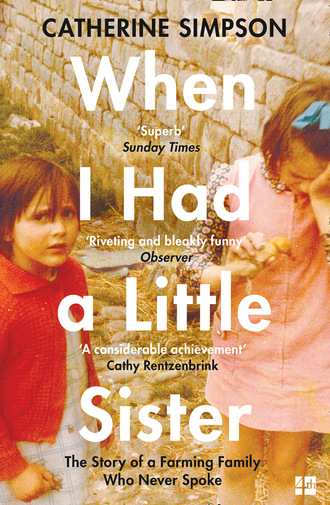

Me, Elizabeth and Tricia, centre front, at the WI Christmas party – my idea of heaven

I liked to get Tricia to myself and on Tuesday evenings, when Elizabeth went off in the car with Mum for her piano lesson, Tricia and I had our own game to play: ‘Hiding from the Germans’. This entailed dashing around the farm from one hiding place or vantage point to another – from among the hay bales in the loft to the back of Gran’s Dairy, from behind the dog kennel (a metal barrel on its side) to the top of the great stone cheese presses in the farmyard we sprinted here and there, flinging ourselves onto our bellies, ‘Ssssh! Keep your head down. Keep quiet!’ as we tried to evade capture and spot the enemy before they spotted us. As a rule we were not a film-watching family and nobody bar Mr Herbert, the vicar, talked about the war (although this was only twenty-five years after the end of the Second World War) so I can only think this game stemmed from watching The Guns of Navarone or The Great Escape or something similar in the sitting room with Uncle George one Christmas Day.

The farm provided great reading hideaways – up trees, on roofs, inside a stack of straw bales with a torch, where I’d read and itch and sneeze. I enjoyed finding a hidden place to escape into a book. Unseen among the branches of a tree or high up on a building I’d watch and think and feel safe. I always knew if Dad or Gran were near by the rattle of buckets.

At other times I’d lie on the back lawn staring into the sky at the white vapour trails from Manchester Airport. Sometimes the longing to be on board a flight was so strong it was an out-of-body experience. It didn’t matter where it was going, anywhere was better than here. Second only to flying away was the dream of a road trip. I watched wagon drivers jealously when they visited the farm, imagining the freedom of the road. Sometimes they’d turn up with a girlfriend slumped in the passenger seat looking bored, chewing gum with her bare feet up on the dashboard among the toffee wrappers and under the rabbit’s foot dangling from the rear-view mirror, and I’d know those girls were truly blessed.

Freedom for me meant wearing no shoes. My sisters and I were never bothered by dirt and as we ran about the farm I never wore shoes, just socks, and I could leap from one dry patch to another, from one clean, flat stone to the next, avoiding mucky puddles and nettles and sharp stones. For many years I half-believed I could fly, just a little, if I willed it hard enough. That is the sort of thing I told Tricia; that I could fly and that she could too if she tried hard enough; if she ran fast enough and didn’t breathe and only touched the ground with her very tippy toes she would fly. I can see her face now as she drank it in, solemn-eyed, amazed but believing it, believing every word I said.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.