Полная версия

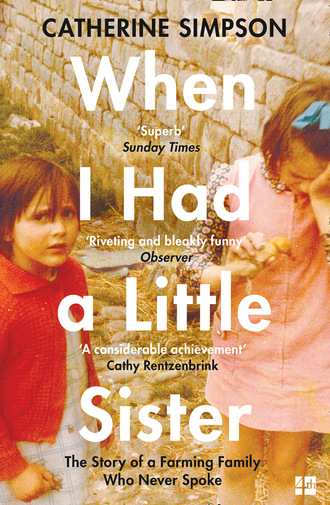

When I Had a Little Sister

Growing up surrounded by all this lingering stuff, with the past and the present and the living and the dead tangled and colliding, it’s hardly surprising that as a child I looked out of my bedroom window and glimpsed Grandma Marjorie, dead since 1938, carrying a basket of washing across the back yard.

By taking photographs of what we were removing, I believed I was in some way keeping the spirit of the thing. It was unthinkable that I should forget. What if I suddenly needed to know the exact shade of blue of Grandma Mary’s old beaded evening gown? The one she wore in the 1970s to meet the Queen. Was it sky blue or was it nearer royal blue? Or what if it was important to recall the precise swirling pattern on the sitting-room carpet? The carpet that was being fitted when half our feral cats climbed in the back of the fitter’s van and were driven off and lost for ever.

I took photographs of Dad’s mummified football boots which had hung on the garage wall for seventy years, of the view from every window, of the texture of the brickwork, the rust on the outhouse window locks, of the flaking paint on the barn door, of the weeds sprouting between the cobbles and the ivy coiling round the fence posts. Turning these story fragments and half-memories into photographs meant the past was not completely lost nor the memories obliterated. All these things were part of our lives here and might in some small way explain how that story ended as it did.

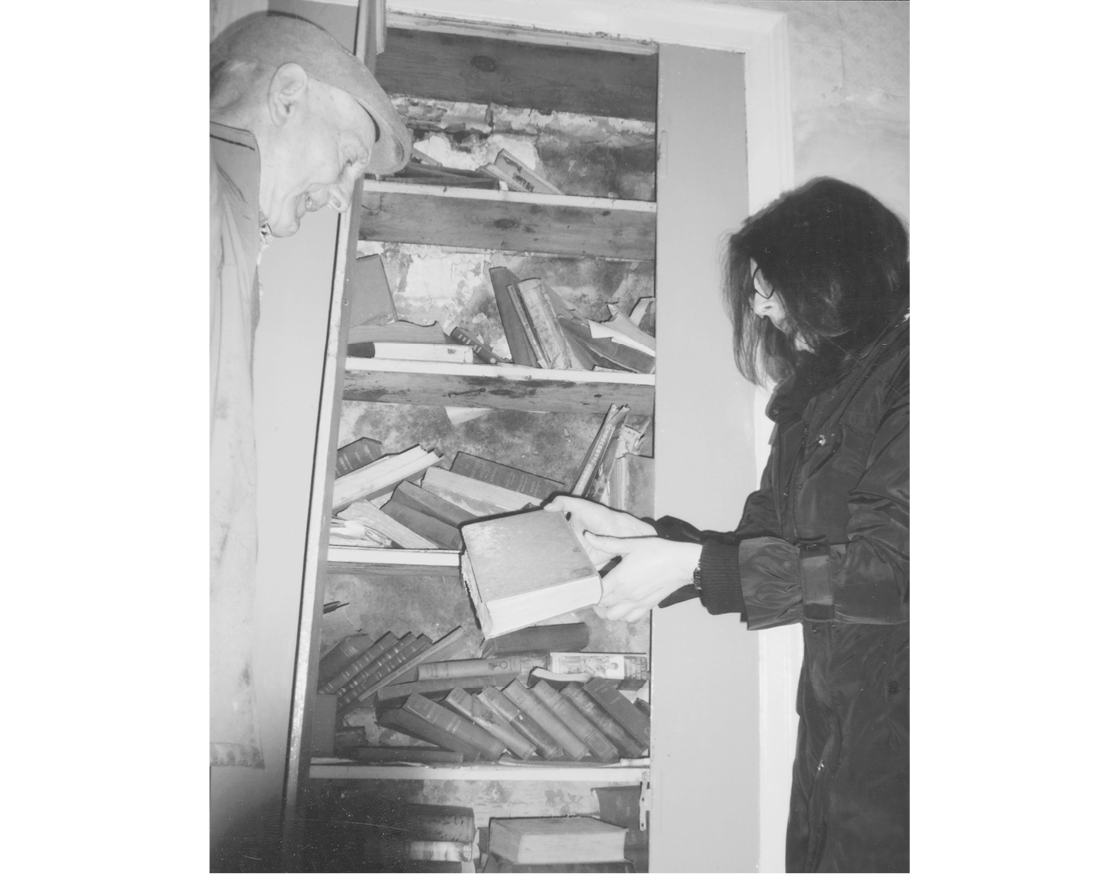

Me and Dad, discovering Ezra the Mormon and The Major’s Candlesticks

I snapped away and heard Lara whisper to Cello, ‘Mum’s just taken a photo of the ground.’

If things could be saved – if they weren’t stinking of mould or half-eaten by moths – we sometimes packed whatever it was into a box and dumped it in Dad’s garage to create a whole new problem for another day, saying to ourselves, ‘Well, you never know.’

I framed a certificate I discovered in the sealed-up cupboard halfway up the stairs that still housed Aunty Marjorie’s Sue Barton books, the paint on the cupboard doors finally cracking from top to bottom as I wrenched them fully open. The certificate was from the Ministry of Agriculture’s ‘1944 Victory Churn Contest’ and had been awarded to the ‘farmers and farm labourers of New House Farm’ for increasing the farm’s milk yield by over 10 per cent during the country’s ‘time of need’.

I took tarnished silver spoons home to Scotland and polished them until they shone, only to let them blacken again without using them. I put the headless dressmaker’s dummy, still set to Mum’s exact measurements, to stand vigil in Dad’s spare bedroom. I gathered stacks of photographs of unnamed, unknown people and tried to persuade aunts and cousins to identify them and take them away, largely without success. Some were marked but the markings left more questions than answers; on the back of one black and white photograph of a man in a suit and spectacles and bowler hat who looked like a bank manager, written in Grandma Mary’s hand was ‘Uncle Percy; cut his throat on a park bench’, or another of a woman in a 1930s dress, written in an unknown hand: ‘My mother.’ When I asked around about ‘Uncle Percy’, no one seemed to know.

As Mum had not liked sharing her things, she had been equally unwilling to share information. Family anecdotes were treated like state secrets and any request for details was greeted with tight lips and a Stop mithering or a What do you want to know THAT for? Telling stories was ‘gossiping’, even if the people involved had been dead for a generation – which meant stacks of photographs were left untethered from their stories.

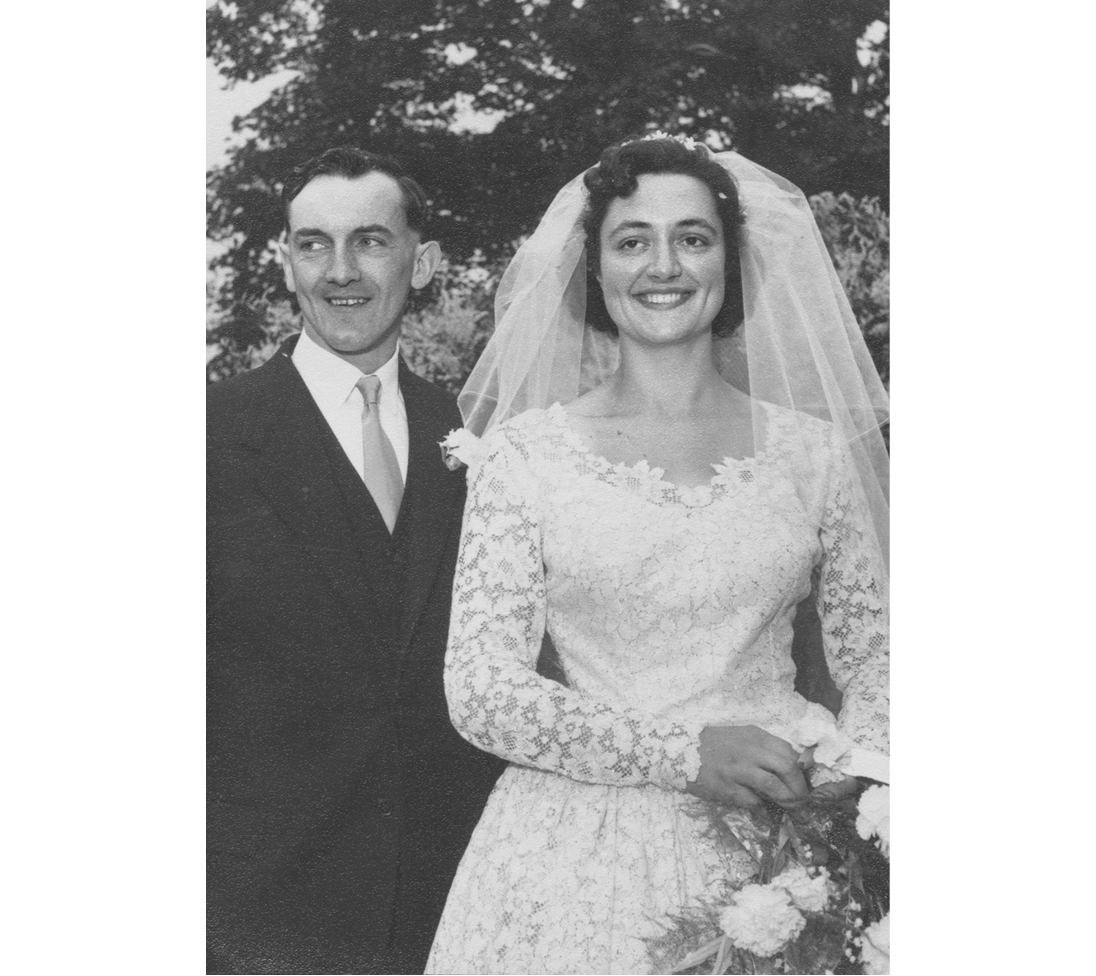

There was a white box of wedding photographs showing my mother and father on the day they married in 1959; my mother beautiful without make-up and in a home-made dress – a lace and duchesse satin creation that could have come from a couture house. A dress I was disappointed as a child to discover she had chopped up to make satin cot quilts for us as babies – a decision that I now see makes perfect sense. In the black and white wedding photographs my father is handsome in a bespoke suit and white carnation and, in some, with what must be a bright red ‘L for Learner’ sign pinned to his back by my mother’s brothers.

As a child I would have revelled in the glamour of these photographs and listened rapt to the details of the day, but those details were never divulged by my mother who kept the pictures out of sight at the bottom of the wardrobe with stacks of wool and material on top. We’d get tantalizing glimpses of the white box but were strictly forbidden to ‘root’. And now it was too late. Now my mother’s memories of the day were lost for ever. My mother wasted an opportunity to talk and to share and it still makes me mad with her, even though she has been dead ten years. What was the point of having these photographs at all if they were to be abandoned to moulder out of sight?

Mum and Dad married in 1959

By contrast my father keeps the brochure for their honeymoon in his desk drawer. He takes out the small blue booklet, Cook’s Motor Coach Tour to the Sunny French and Italian Rivieras, Taking in London, Grenoble, Nice, Monte Carlo, San Remo and Paris, at every opportunity to tell us again about the casino in Monte Carlo and the ‘Paris by Night’ coach tour on the way home. This must have been quite some tour in 1959; the brochure’s instructions hint at the novelty of the trip: ‘It is not practice for hotels to provide toilet soap and it is recommended that you take your own soap and at least one hand towel … Cameras can be taken on the Continent, and films purchased quite easily … As there may be opportunities for bathing you may wish to pack a bathing suit … Sunglasses will add to your comfort … Baths (unless you have booked a room with private bath at a supplementary charge) and afternoon teas are not included.’ Torquay or, God forbid, Blackpool would not have done for my mother, but whenever Dad talked about their glamorous trip she’d respond with a dismissive wave of the hand. Who wants to know about that?

When we were left with only heavy furniture in the farmhouse we called a house clearance cum antique dealer who sent along a pair of rough-looking blokes called Pete and Trev. Pete and Trev pulled up outside with a van already packed, and with no apologies for being two hours late. The things we wanted them to take included the enormous bedroom suite my father’s parents, David and Marjorie, had arrived with in 1925 as newly-weds. This suite was heavyset mahogany elaborately carved with leaves and flowers and smelling of camphor. There were four pieces: a wardrobe with an arched bevelled mirror, a marble-topped washstand, a dressing table and a bedside cupboard with a shelf for a chamber pot.

As Pete and Trev sauntered about the farmhouse their eyes never looked where we pointed but flickered around each room, alighting briefly on everything else. Furniture was touched, smoothed, handled, turned upside down, and pronounced upon with a shaking head. ‘Brown furniture, you can hardly give it away these days,’ said Pete or Trev. ‘It’s all IKEA now.’ Pete or Trev grimaced. ‘A piano? It’d cost me more to take it than to leave it. The last one – I couldn’t give it away – had to get it dropped from a crane to break it up.’ Cupboard doors were opened and shut; drawers were slid in and out, out and in, removed, twizzled round. ‘Where are the drawers for this Georgian chest?’ asked Pete or Trev. Unfortunately the answer was ‘on the bonfire’. ‘Where is the other table from this G Plan nest?’ We looked at each other; maybe our eyes flickered to the window with the view of the bonfire. Nest? Was there another table as ugly as that one? Eventually Pete or Trev brought out a roll of banknotes from a trouser pocket and rapidly peeled off several. ‘Three-fifty and it’s off yer hands.’

There was almost a hysteria by now about finishing this task which had been generations in the making. The decisions we made were hasty and getting hastier because Elizabeth and I lived hundreds of miles apart and so we did the job in bursts at weekends. It felt at times as though we would never get to the end of it. I had the sensation of trying to free myself from a sticky cobweb that clung relentlessly, refusing to let go and entangling me further no matter how hard I grappled.

Not long after Pete or Trev paid us for the bedroom furniture we found a list of wedding presents, handwritten by Marjorie in 1925, headed up ‘Walnut Bedroom Suite – given by Mother and Father’. So it was walnut not mahogany. I felt a guilty stabbing – what were we doing? – before common sense reasserted itself.

As the house became emptier and brighter it seemed physically to lighten and relax. When David and Marjorie’s enormous bedroom suite was finally removed by Pete and Trev ninety years after it arrived, it was as though the house had lost its anchor or had its roots severed. The farmhouse was now empty and echoing and it seemed there was every chance that, unencumbered by our family detritus, I might return to it one day and find it had gone – that it had floated entirely away.

Chapter Six

My sisters and I were born at New House Farm in the sitting room; the same room in which my dad was born thirty-eight years before me; a room otherwise only used on Christmas Day to watch films and eat Quality Street; a room that would one day have Pete and Trev strolling round it talking about pianos and cranes and brown furniture as they weighed up brass pots and pieces of china and searched for marks on the silver.

Me and Elizabeth ‘helping’ Dad mend a puncture around 1966

On the day I was born, Nurse Steele came with her canister of gas and air to deliver me, as she had done three years earlier when Elizabeth arrived and as she would do three years later for the birth of Tricia.

On that occasion Elizabeth and I were not told what was happening in the sitting room directly below our bedroom. We woke one morning to discover our bedroom door so firmly shut it was impossible to open. Was it locked? Were we trapped? We hammered and screamed ‘Help! Help! Mummy! Mummy!’ until Dad wrenched the door open. ‘Sssh!’ An aunt took us downstairs and gave us Chocolate Fingers and milky coffee in front of the kitchen fire to keep us quiet until we were eventually taken into the sitting room for the first sight of our new sister.

We were led through the lobby and the sitting-room door, past the grand piano, until I was on eye level with the bed that my father had brought downstairs the week before for the arrival of this baby. Mum was propped up against the pillows, smiling a little, wearing a crocheted bed jacket with satin ties. Tricia was lying on the counterpane wrapped in a white blanket. I think Mum probably decided not to be cuddling Tricia as we came in for our first look so we wouldn’t be jealous.

Nurse Steele said, ‘Isn’t she lovely?’ and I stared at this red-raw mewling thing moving in slow motion. I looked sidelong at the smiling nurse – was she laughing at me? Why was she saying it was lovely? I felt betrayed. This was not the playful, chubby-cheeked baby I had been promised – the one I could be ‘good’ with and share my toys with; I was doubtful it was even a baby at all. It reminded me of new kittens when you first found them in the barn in the nest; eyes shut and rooting for milk. Nurse Steele gave a tinkling laugh and I looked at the carpet.

Someone had played a dirty trick on me.

Years later Tricia claimed she could remember being born – the violence of it, the darkness, the eventual light. When I told Mum she snorted and rolled her eyes. As if!

She banged her Daily Express, with an expression like Whistler’s mother, and that was the end of it. Perhaps the act of childbirth was below my mother’s dignity and she didn’t want anyone remembering that.

In our family, it seemed sitting rooms were for Christmas, for being born or for dying. This was the first room you saw, and the last.

The first dead person I saw was in 1973 when I was nine years old and I was taken to see my maternal grandad lying in an open coffin in the best sitting room of my grandparents’ farmhouse. We rarely got to see the inside of this room but there was no time today to examine the upright piano or the cabinet of china ornaments – including a china cat about to kill a cowering china mouse – or the eight black and white wedding photographs of my mother and her seven siblings framed and hanging on the wall like a catalogue of wedding styles through the 1950s and 60s.

No, today the settee had been pushed back against the piano to make room for the coffin, which was shiny oak, top of the range, and resting on some kind of stand. Grandad Ben was wearing a white satin shroud and was surrounded by white satin padding. He had died of lung cancer after being ill for only two months. He had rapidly grown thinner and weaker and his cheeks had sunk but nobody had told me he was dying.

His bed had appeared unannounced and unexplained in the living room of my grandparents’ farmhouse where the old sofa used to be – the one we sat on to watch The Golden Shot and Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased) on a Sunday afternoon while we ate finger rolls with mashed egg and salad cream followed by Great-Aunty Margaret’s jam slice – and he had gathered ever-more bowls and containers around him to cough and spit into; but still nobody told me he was dying.

Illness was frightening; adults whispering and shaking their heads was frightening. Frustrated that he looked worse every week and puzzled when Grandma smiled a little too brightly and said, ‘He did so well!’ when all Grandad had done was walk to the bottom of the yard and back, I asked my mother: ‘When’s Grandad going to get better?’ She was stirring a pan of gravy with a wooden spoon and kept her eyes on it and said, ‘Maybe he won’t.’

Shock trickled from the top of my head to the tips of my toes like a bucket of iced water. I had never considered there were important things grown-ups could not fix.

I wondered if my mother would ever have told me if I hadn’t asked.

When he died my mother asked me and my sisters if we wanted to go and see him. Grandad was six feet tall, a strong farmer with a forceful personality, and now here he was in his coffin looking like a waxwork. We were told his body had been embalmed so he would never change. This, I understood, was because Grandad was a Very Important Person; someone his family looked up to and respected without question. Grandad was a Worshipful Master in the local lodge of the Freemasons; Grandad was a Duchy of Lancaster tenant and had been invited to meet the Queen at St James’s Palace more than once; Grandad had played rugby for the Rochdale Hornets and as a young man had been sparring partner for professional boxer Jock McAvoy, known as the Rochdale Thunderbolt; Grandad was a personal friend of Gracie Fields and on the marble mantelpiece by the television was a postcard from the island of Capri to prove it, curling at the edges and a little singed from when it had drifted into the open fire, but still legibly signed ‘best wishes, Gracie’. Grandad was all-knowing, all-powerful and immortal.

We edged towards the coffin. I could see Grandad’s profile; it was him and yet not him. I wasn’t sure that embalming was such a good idea if it meant he would look like this for ever. His hands lay white and frozen on the shiny satin shroud. They looked different; they looked very clean. A farmer’s hands never look very clean, no matter how much they scrub them with globs of Swarfega. I learned years later when my own father was ill in hospital with the first of his bouts of cancer that if a farmer’s hands are not ingrained with soil he is either dangerously ill or he is already dead.

My mother leaned over the coffin and kissed Grandad’s cheek and I watched, horrified. I’d never seen my mother kiss anyone before, let alone a dead person.

I’d been reluctant to kiss Grandad when he was alive because he and my uncles had a habit of grabbing your face and rubbing their stubbly chins on you. This painful experience was known as a ‘chin pie’ and was supposed to be funny. It certainly made my uncles roar with laughter but it had made me wary. I knew on this occasion Grandad was not going to give me a chin pie but I still didn’t want to kiss him.

Elizabeth, Tricia and I inched nearer the coffin, side by side, halting at a safe distance. Grandad had been a generous man who regularly went to the cash-and-carry to buy sweets in wholesale quantities for his grandchildren and handed them out like Father Christmas every Sunday, yet bellowed at me for switching on the stair light in the farmhouse to find my way to the loo because I thought the turn in the creaking stairs was haunted. Grandad was a man who read Titbits yet disapproved of many things including a child using the word ‘pregnant’ (‘don’t let your grandad hear you saying that word’). Grandad travelled the world with Grandma Mary, including cruising to South Africa, yet I once saw him pluck a partially sucked sweet off my cousin’s jumper, say ‘waste not, want not’, and eat it. I had joined in games where he sat beside a doorway and tried to whack you with a rolled-up newspaper as you ran past, partly excited but mainly terrified.

‘Say goodbye to your grandad,’ my mother said. She started to cry. I watched, frozen.

I’d never seen my mother cry before either.

I learned when Grandad died that certain rituals follow a death; relatives gather together and speak in undertones and drink tea, but as kids my twenty-odd cousins and I had not yet learned to respect these rituals. On the Sunday after Grandad’s death, but before his funeral, we played Blind Man’s Buff along the farmhouse corridor like on any ordinary Sunday; except this time not only were we trying to evade the blindfolded ‘blind man’, we were trying not to touch the sitting-room door because it had dead-Grandad behind it. If one of the younger cousins stumbled against the door an older cousin would chant, ‘You’re haunted! You’re haunted!’ and the younger cousin would start blubbering, whereupon an aunt would poke her head out of the kitchen and hiss, ‘Ssssh! Don’t you know your grandad’s dead?’ as though there was a danger our racket would wake him up.

I wanted to go to Grandad’s funeral but was told, ‘No, and don’t ask again.’ Neither Elizabeth nor Tricia expressed any interest in going. My mother was knocked sideways by the death of her father and she probably thought she had enough on her plate without taking me. I considered this unfair – especially as this was not the first funeral I had been banned from attending.

Five years earlier, when I was four, I’d asked to go to my first funeral when Old Jack died.

Old Jack was our neighbour and looked like a manifestation of God himself – if God ever wore fustian breeches and lived in a red-brick cottage in the middle of Lancashire. He had white hair, a white moustache and a mahogany desk full of chocolate.

We took up his dinner (his midday meal) every day on the tractor the quarter of a mile from our farm. My dad drove and Elizabeth and I bounced along clinging to the tractor cab, struggling to keep the plate straight to stop the gravy and the peas from dribbling into our wellies.

We’d find him sunk in his armchair by the open fire. He wore a jacket and weskit and trousers shiny with age and of an indeterminate colour best described as ‘old’. He had pockets of mint imperials and barley sugars.

He was glad to see us and would greet us with a ‘How do’ and creak out of his chair and root around in his antique desk to find each of us an Aero bar. The desk had shiny black knobs down each side and soft fraying leather on top and a secret drawer. Old Jack showed us how to slide out one of the knobs to open the secret drawer.

Old Jack’s cottage had no running water, no electricity and no gas. It was 1968, and by then his wife had been dead more than thirty years. Old Jack had lived there on his own since his brother Old Jem died of lung cancer in 1962. Old Jem had never smoked but had spent every night huddled over the coal fire in the cottage to keep himself warm. Old Jack had had two brothers and a sister, all unmarried, who had lived with him after his wife died and who themselves then died at seven-year intervals – Agnes was the first to go in 1948. She was a woman with an ‘erratic mind’ who ‘fizzled out somehow or other’, as my father remembers it. Seven years later Bob shot himself with a 12-bore shotgun on the back cobbles of the cottage. Bob was seventy years old, newly retired and unable to face life without his job on the dykes.

My dad had been visiting Old Jack every Sunday evening since the 1940s and for years there had been games of Nap and Pontoon, with Agnes, Bob and Old Jem, playing for pennies; the oil lamp rocking on the table as they excitedly slapped down the cards.

By the time Old Jack died in 1968 we’d been delivering his meals by tractor every day for ten years and we were the closest thing he had to family.

A year or two earlier when Old Jack was well into his eighties, he’d turned up at our farm on his bike with his Last Will and Testament shoved in his weskit pocket. He was leaving the lot to my dad and another neighbour, he said; his tiny cottage, its contents and his ten-acre meadow with his cow in it. To Elizabeth he was leaving his ebony and gold antique chiming clock, to my baby sister Tricia he was leaving his Edwardian sofa, and to me he was leaving the loveliest thing I have ever been given – the beautiful antique writing desk with the shiny black knobs and the secret drawer full of chocolate.

Old Jack died ‘of old age’ in his sleep when he was eighty-six and he was laid out in an open coffin in the cottage’s tiny sitting room. I was four years old and wanted to go and see him.

‘I want to see Old Jack.’

‘No.’

‘I want to see him.’

‘Stop mithering.’

‘What does he look like?’

‘Like he’s asleep. Now stop mithering.’

‘Is he in bed?’

‘No, he’s in a coffin.’

‘What’s a coffin?’

(Sigh.) ‘It’s a box you get buried in. Now that’s enough.’

‘What kind of a box?’

‘Oak with brass handles. It’s a box that’s oak with brass handles.’

I thought about this. A few years later I would learn about oak boxes with brass handles; I would see them on The Dave Allen Show where they were usually balanced on the crossbars of bikes or slithering out of vans and sliding down hills chased by the vicar. But at the age of four I had never seen one and they intrigued me.

‘Can I go to the funeral?’

‘No.’

‘Why not?’

‘You’re too young.’

‘Why?’

‘Children don’t go to funerals. Don’t ask again.’

‘Why?’

‘Ask again and you’ll go to bed.’

Dad brought the antique desk from Old Jack’s with the tractor and trailer. He wrapped his long arms round it and staggered into the house with his knees bent. Unlike with Great-Great-Aunt Alice’s bracelet and evening bag, my mother did not consider the desk rubbish. She said, ‘That desk’s mahogany, it’s a Davenport – put it straight in the sitting room.’ That meant I’d only see it on Christmas Day or if somebody was born or if somebody died.

It was not going in my bedroom because it would get ruined. It was too good, my mother said. It was too good to get scribble gouges and felt-pen marks and cup rings on it. The mahogany desk was going in the sitting room and that was that.

Occasionally over the years I would turn the brass knob on the sitting-room door and push the door over the thick carpet and stare at the mahogany desk wedged between the grand piano and Tricia’s Edwardian sofa. It was a long way away; acres away over the swirling turquoise and gold carpet and flanked by tarnished photograph frames and piles of sheet music and china vases that I wasn’t allowed to touch either. It was far, far away – much farther away than it had been in Old Jack’s living room. It was not covered in scribble gouges or felt-pen marks or cup rings. It was not ruined, but its secret drawer was never opened and no one ever stroked its frayed leather top. No, the mahogany desk may not have been ruined but it was dusty and fading and empty of chocolate and so far away it was lost to me.