Полная версия

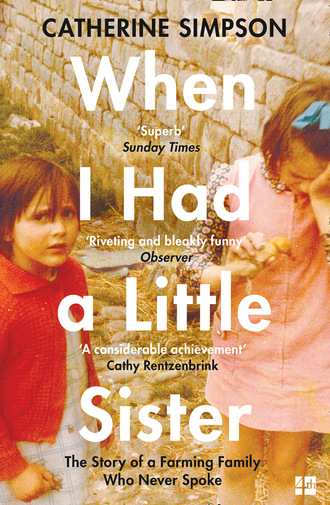

When I Had a Little Sister

Eighty years later my dad keeps a postcard in his desk, addressed to ‘Master Stuart Simpson’, sent by his mother from hospital in Preston as she waited to give birth. The card shows a painting of a spaniel. ‘Wasn’t Preston lucky on Saturday. I heard it on the wireless. Hope you are doing your best for Daddy.’

He still cries when he sees it.

Also in his desk is the bill from the hospital for the maternity services his mother received. A bill issued to her husband after her death.

Grandma Marjorie was survived by her baby girl, who was also named Marjorie. As a girl, Young Marjorie was red-haired and sparky. She worked on the farm, throwing herself into everything – baking with gusto and covering herself and the kitchen with flour, chopping logs and accidentally hacking her finger-end off with the axe. She got engaged to a local undertaker called John but Young Marjorie had a digestive disorder and no one realized how serious it was until she collapsed and died. Instead of being married in 1959 she was buried. This was four years before I was born. She was twenty-one.

Young Marjorie, aged 21, the year she died

I think it was in 2005 that the Kilner jars of damsons, picked from the orchard and bottled by Young Marjorie, and that had been lining the far-pantry shelves my entire life, were finally thrown out.

It took me a long time to realize that Grandma Marjorie was so scarcely mentioned I didn’t have a proper name for her and had settled on ‘Dad’s Mum’. Stories about her were rare not because nobody cared but because Dad and Gran cared so much. On this subject, as on so many others, we were dumbstruck.

In my lifetime the cupboard halfway up the farmhouse stairs had been painted shut with layer upon layer of thick gloss paint. As a child I pressed my eye to the keyhole, shone in a torch and saw book spines untouched for more than twenty years.

Books were my escape from a world with the wrong kind of drama in it. I hungered for stories and books to make reality fall away.

I read to find circuses, wild animals, long dresses, castles, enchanted forests and magic faraway trees. Re-entering real life after being lost in a book was painful and disorientating.

At the table I read the back of the cereal packet. I read the primary-school library over and over again. I read the set texts Elizabeth brought home from secondary school: Animal Farm, White Fang, The Otterbury Incident. I read the Daily Express. I read the Radio Times. When I ran out of stories I read the dictionary. I compiled my own dictionary of words I didn’t understand. ‘Tippet: a woman’s shawl; Brougham: a horse-drawn carriage; Stucco: plaster used for decorative mouldings’ reads the list, in what must have been a Georgette Heyer phase.

Until sixth-form college my reading was unguided so I read Tender is the Night but not The Great Gatsby, Anna Karenina but not War and Peace, Lady Chatterley’s Lover but not Women in Love. I chose books from Garstang Library purely on covers and titles. I read the entire works of P. G. Wodehouse and Agatha Christie, fascinated by their versions of English country houses. I read everything Catherine Cookson wrote and pronounced ‘whore’ with a ‘w’.

My mother brought back library books in the Ulverscroft Large Print series for me, knowing I wore glasses without understanding they were for distance not for reading. Producing a child who needed glasses was perturbing for my mother: ‘I fell down stairs when I was expecting. I didn’t make such a good job of you.’ I never told her I could read small print perfectly well, because I liked getting lost in the great big words.

But my mother did give me occasional random compliments. ‘Your ears lie good and flat. The back of your head is well shaped. Your eyebrows suit your face.’

I was short of books and often panicked about it, so one day I prised open the cupboard door on the stairs as the hinges made sharp cracking sounds and splinters of paint flaked off. Inside were dusty and faded hard-backed books. I inched one out and shut the door, pressing the cracked paint on the hinges back into place. The book was Sue Barton, Senior Nurse and was signed on the flyleaf ‘Marjorie Simpson, 1956’.

I took it downstairs and sat on the hearthrug in front of the open fire. My mother said: ‘What’s that? It looks like rubbish.’ I struggled through a few pages but there was no adventure here; it seemed to be about nothing but a nurse in trouble with ‘Sister’ for being on the ward with her ‘slip’ showing. My mother was right, it was rubbish. I squeezed my hand again between the painted-up doors, scraping my knuckles as I put Aunty Marjorie’s book back in the past.

I have wanted to be a writer for as long as I’ve been able to read. I wrote my first book aged nine in a hard-backed Silvine notebook with marbled endpapers. It chronicled the adventures of ‘Sandra’ and ‘Barbara’ – two girls who apparently went everywhere (mainly to dancing lessons) on horseback and had a sworn enemy called Mr White. My best friend, Alex, and I acted out the adventures of Sandra and Barbara every day in the school playground.

My writing ambitions faltered after that because writing became embarrassing; self-indulgent and pointless, particularly after a boyfriend found something I’d written when I was a teenager and flicked through with a sneer on his face. ‘What is this? What do you think you are – a writer?’ Later I discovered he had scrawled in the margin ‘This is stupid’, in case I hadn’t got the message.

My mother read gardening books, dressmaking books, yoga books and recipe books, but no fiction. She referred to fiction as ‘made-up stuff’, and asked ‘why do you read that?’

I left school at eighteen with dismal A-level results and became a bank clerk then a civil servant, jobs taken for the sake of taking a job – because that’s what you did. I also had to pay the mortgage I’d saddled myself with aged nineteen – because buying a house was something else that you did. In my mid-twenties I retrained as a journalist because that seemed an acceptable way to earn a living with words. My mother died when I was forty-two and shortly after that I began to write pieces of fiction and memoir. It took me until my first novel was published, when I was fifty-one, to realize the death of my mother and the birth of my writing were linked – that in losing my mother I had acquired the right to write my own life.

Chapter Five

After Tricia died the thought of what would be involved in clearing the farmhouse was terrifying.

A few years earlier I had viewed a house for sale in which the owner had died of a heart attack only days before and I had been appalled to see bread on the kitchen units that was still in date and the dead owner’s appointments on the calendar for the following week: Coffee with Bernard, 2 o’clock.

Families move at different speeds. Tricia had been dead six months when Dad said, ‘What about doing something wi’ yon house?’ and we knew we couldn’t put it off any longer. At first I thought we’d get a skip, but no, Dad built another enormous bonfire in the orchard – this time away from the telephone wires – and, bit by bit, we ferried generations of possessions onto what was in effect a funeral pyre.

Not knowing what to do with many things with sentimental value, we threw them into a ‘Memory Box’, actually a yellow cardboard box in which my new boots had just arrived.

These were the things we saved:

Tricia’s childhood jewellery: tangled silver chains, little charms and bent and twisted earrings; her drawings and paintings, watercolours of cats and dogs and horses and self-portraits; photographs of Tricia with friends we didn’t know in places we didn’t recognize. I studied her face, scanning her expression for signs of distress – did she want to be there? Was she enjoying herself or was she desperate to be alone, smoking? Was that a false smile? Was she suffering? Was that one of her good days or one of her bad?

We saved stacks of her notebooks and diaries that I couldn’t bear to read – including the notebook that the police officer had removed along with her body. ‘She wrote a lot, didn’t she?’ he said the following day when he returned to take down more details. Elizabeth was angry. We did not know what she’d written in that notebook so why should he? Apparently, though, the book did not shed any light on her thoughts on her last night on this earth – it did not contain a suicide note. We were allowed to have it back after the inquest, except by then it was lost. Incensed they had been so careless with her things, we asked the Coroner’s Office to chase it up until the police found it and hand-delivered it to Dad’s in a sealed envelope to stop him reading it and getting upset.

We saved Tricia’s soft toys. How do you burn a teddy bear you remember from childhood, no matter how filthy? We saved a home-made sheep, a rock-hard badger and a gangly Pink Panther. Who made these? Nobody could remember. It was probably Mum’s mum, Grandma Mary, who took up handicrafts with a passion after her husband, Grandad Ben, died – sublimating her grief in patchwork dogs, hessian dolls and punched leather work.

We saved Tricia’s one-legged Tiny Tears doll called Karen who we found naked except for a bikini drawn on in green felt pen and wrapped in Mum’s old fox fur with its flat nose and glass eye. Karen and the toys were rescued from the farmhouse only to be flung on a rocking chair in a corner of Dad’s house where they remain, described by my teenage daughter, Lara, as ‘that pile of old weird shit’.

We saved sherry glasses – stacks of sherry glasses in styles ranging from the delicately etched of the 1930s to the clunky and chunky of the 1970s – even though we had never drunk sherry except at Christmas. Where had all these sherry glasses come from? Dead great-aunts? Grandma? No one could remember but we took to drinking Harveys Bristol Cream before supper.

I saved a page of doodles I discovered with the words ‘My name is Nina, and I am brilliant and I must not forget it’ written on, surrounded by trees and hearts, shoes and cats. I framed it and hung it on my daughter, Nina’s, wall.

Although many items had been removed in the weeks after Tricia died, there were still plenty of things dangling in the wardrobe. I saved clothes that would never fit me and would never be worn again even if they did but that I remembered Tricia wearing, including the twenty-year-old bridesmaid’s dress she wore at my wedding. We saved a flowery skirt that I turned into a cushion, a dress I turned into a jumper and a jumper I turned into a hat. We saved broken beads to be made into Christmas decorations. We saved her piano certificates. We saved her swimming badges, from 50 metres to bronze lifesaving, which were still attached to her red stripy swimsuit. Going to ‘the baths’ at Lancaster had been a big deal. The first time we went I must have been about seven and expected it to be one big claw-foot bath like we had at home. I wore a swimsuit with polystyrene floats fitted round the waist – a costume rejected by Tricia. I gazed, fascinated, at the sign NO RUNNING, PUSHING, SHOUTING, DUCKING, PETTING, BOMBING, SMOKING with its helpful cartoon illustrations and I clung to the side as Tricia set off on tiptoe, splashing across the shallow end seemingly unconcerned by water lapping at her nostrils. It was similar to the only time we went ice skating. Then I’d gripped the safety rail while Tricia’s game spirit was spotted by a stranger – a middle-aged woman – who led her around the rink. By the end of a torturous hour for me they glided serenely back, side by side with crossed hands, like something off a Victorian Christmas card. Tricia was always braver than me.

Some things were easy to burn: the piles of medication in blister packs, which went straight on the bonfire, as did stacks of appointment letters from the mental-health services. We burned her last packet of fags – the pack of ten with the four missing that we found on the bathroom floor – but by then I regretted we hadn’t put these with her in the coffin. Tobacco had been a good friend to Tricia.

Many things were hard to burn; for instance her socks. Cello cried as he emptied her sock drawer onto the bonfire and watched Dad stopping the balled-up socks from rolling out of the flames with his big stick.

Sometimes we got cavalier. I tossed a toilet bag into the fire without checking carefully enough what was inside, only to discover too late that it contained aerosols and sealed tubes that exploded and sent my father diving for cover behind the giant bamboo.

During the weekends of clearing, the flames burned bright throughout Saturday afternoon and if they began to flag Dad would douse them in diesel and they’d soon be ten feet high again. The bonfire would still be smouldering on Sunday morning which meant we could continue; sofas, mattresses, damp quilts and bedspreads, all the velvet curtains, carpets, lino, on they went.

It felt cleansing and became addictive; you’d find your eyes scanning a room for flammable materials. A battered screen! Dried-flower arrangements! More wool! Let’s drag them out and burn them!

Once the rooms were empty we started pulling off wallpaper that hung loose and damp in places – great lengths of woodchip painted in shiny turquoise and mauve that came away bringing layers of plaster with it. We’d bang the flaking plaster with a brush until it all fell and we had at last got back to a sound surface. We wrenched off sheets of plasterboard that had been used to box in original features in the 1970s, to reveal wallpaper from the 1950s with hand-painted roses and lily of the valley.

To watch dusty, neglected, largely unloved items set alight, burn, smoulder and turn to ashes felt right. It also felt very warm and, despite it being summer when we did the clearing, the heat on my face was comforting and gazing into the heart of a fire consuming my family history was mesmerizing.

As a seven-year-old, I had watched the disposal of my Great-Great-Aunt Alice’s things and been fascinated by the dismantling of a life, fascinated to see someone’s life story being taken apart into its bits and pieces and each one being held up to the light, valued in some way, then kept or discarded.

There were legends about Great-Great-Aunt Alice: she was a suffragette; she founded her own bus company between Manchester and Blackpool; she was a ‘man-hater’ who married a much younger man only to pay for him to go to Australia and never come back. It was said she was so tight with money she reused old stamps. She was a hoarder whose bungalow was only navigable via narrow corridors between the piles of junk. She nearly killed herself by keeping warm with an electric fire placed on the bed because there was nowhere else to put it and which then set the bedding alight; and, as recalled by one uncle, ‘she had a dirty parrot who shit everywhere’.

But you only heard these legends if you asked, because Great-Great-Aunt Alice had no children and so when she died she began to fade fast into history.

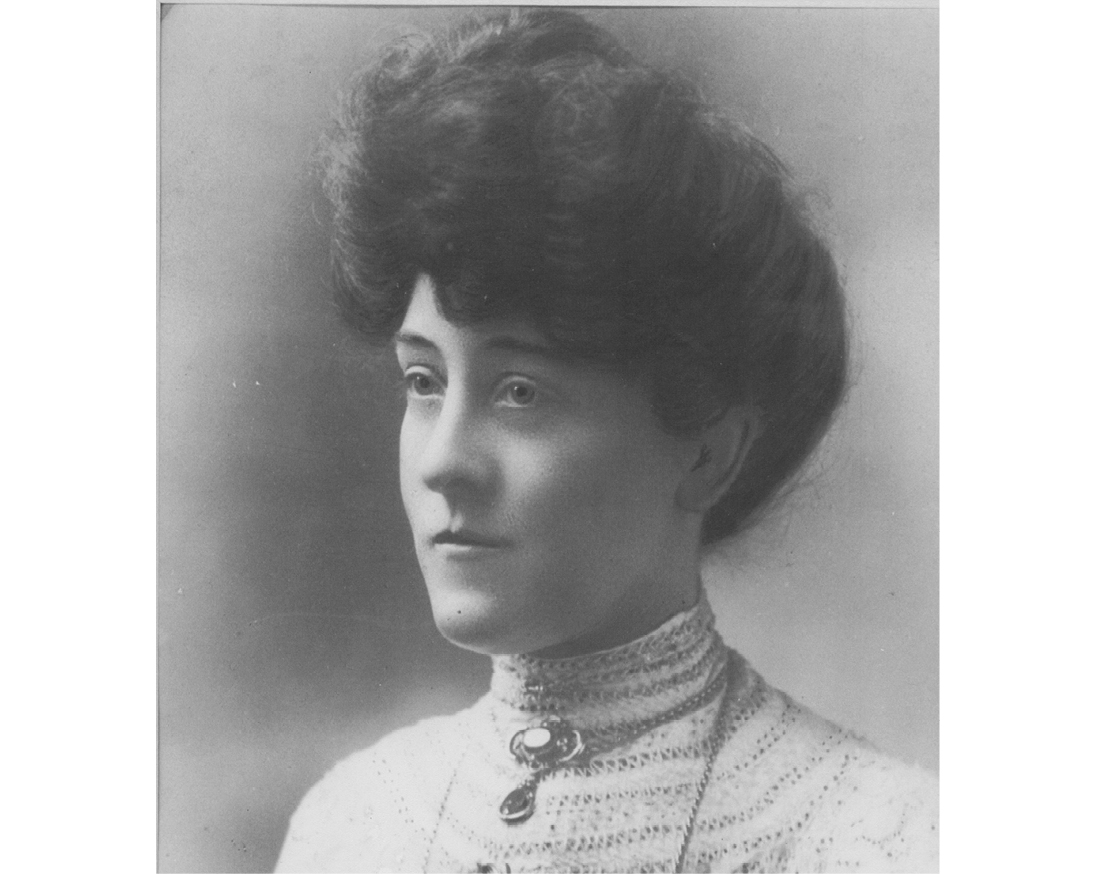

Great-Great-Aunt Alice: suffragette, businesswoman and hoarder

I have her photograph on my living-room wall in my gallery of ancestors. The picture dates from around 1914 when she was in her mid-twenties. She is wearing a high-necked Edwardian blouse and two thick gold chains with pendants of amethyst and quartz. She has a cameo brooch pinned on one side and a gold nurse’s-style watch on the other. Her hair is swept up into a chignon and she stares past the camera with a determined expression. She is clearly a woman who amounted to something.

When I was six or seven she was very old and dying and she came to stay for a few weeks with Grandma Mary. Mum and I went upstairs to take her a bowl of prunes on a tray. The air hung heavy in the bedroom where Great-Great-Aunt Alice was a small hump under the bobbly candlewick counterpane. Her little grey head turned as we entered.

She struggled to get her tiny shoulders up onto the pillow so she could taste the prunes in their sticky brown juice. The spoon shook in her hand and clacked against the rim of the bowl and dribbles of juice trickled down her chin. In a loud and forced-cheery voice Mum said, ‘We’ve come to have a look at you,’ which was the usual greeting in our family, but Great-Great-Aunt Alice said nothing; all her fading energy was concentrated on getting the prunes onto the spoon and up into her toothless mouth.

Being so infirm, taking so much effort to raise a spoon to your mouth, and to suck and to swallow, to not be able to talk, to want to eat prunes at all – this looked to me like somewhere between life and death, but nearer to death.

A week or two later we went to Grandma Mary’s for the usual Sunday afternoon visit and Great-Great-Aunt Alice was nowhere to be seen. Instead there were Great-Great-Aunt Alice’s things; boxes and boxes of shoes and handbags and petticoats, so many things that the big farmhouse kitchen was like a jumble sale. I particularly remember the petticoats in satin and silk and watching Tricia and Cousin Elaine clop past wearing one each, lifting them up like Cinderella’s ball gowns as they clattered and wobbled by in Great-Great-Aunt Alice’s shoes. There was a reek of mothballs.

One of my uncles held up a great pair of white bloomers and said, ‘Run them up a flagpole and folks’ll know you’ve surrendered,’ and everybody laughed.

We poked through drawers that had been removed from chests and dressing tables, which must have been brought from Great-Great-Aunt Alice’s bungalow after her death and dumped on Grandma Mary’s kitchen table. They were filled with the usual stuff that accumulates in drawers: dried-out pens, purses with the odd sixpence inside, bottles gummed up with the residue of sticky yellow cologne, tickets for long-forgotten trips, postcards from long-lost friends. In the grime in the corner of one drawer an aunt found a garnet and seed-pearl ring and trilled, ‘Is it finders keepers?’ Grandma, who was standing at the kitchen unit slicing boiled eggs for tea with a plastic and wire contraption, didn’t look round and said, ‘Take what you want.’

I left with a bracelet of coloured stones and an evening bag all silky inside and infused with a lingering scent of a long-ago perfume. I was delighted to own such glamorous things, and, as both the bracelet and the bag were considered rubbish by my mother, I was at liberty to drag them around the farmyard with me until both the bag and the bracelet were broken and lost.

Many years after the disposal of my Great-Great-Aunt’s things I read Mrs Gaskell’s Cranford. In it Miss Matty burns her parents’ love letters.

‘We must burn them, I think,’ said Miss Matty, looking doubtfully at me. ‘No one will care for them when I am gone.’ And one by one she dropped them into the middle of the fire, watching each blaze up, die out, and rise away, in faint, white, ghostly semblance, up the chimney, before she gave another to the same fate.

I ask myself now: is it possible to dispose of a person’s effects with dignity?

Some months after writing this I discussed these memories with my Cousin Mary. She remembered all the stories of Great-Great-Aunt Alice; yes, she did indeed buy her husband a one-way ticket to Australia, writing ‘liar, thief and all that is bad’ on the back of his remaining photograph. And yes she was a suffragette and made money in stocks and shares and in business, and tried to keep warm by putting the electric fire on the bed – and she did set the bed on fire. But here my memory proved faulty. The bed-fire had in fact killed Great-Great-Aunt Alice after a short hospital stay. So who was the tiny grey-haired lady eating prunes whose stuff we had shared out? It turned out to be another unmarried, childless great-great-aunt called Annie. And this underlined for me that after death not only do we disappear and our belongings become scattered, but our stories begin to blend with the stories of others and meld and shapeshift like a flock of murmurating starlings.

A few years after Great-Great-Aunt Alice (or, as it now seems, Annie) died, my Great-Aunty Margaret died too, also leaving no children, so the contents of her seaside bungalow went up for public auction. I had moved away by then and didn’t go and afterwards I asked Mum what had happened to Great-Aunty Margaret’s most prized possession – her silver epergne, an elaborate candelabra centrepiece that she displayed on her sideboard, proudly telling everyone it had once belonged to Rochdale Town Hall. My mother said, ‘She’d polished it so much she’d worn the silver plate off.’ She shrugged. ‘Somebody must have bought it, I suppose.’

Great-Aunty Margaret suffered from dementia and as it progressed she told us the same stories over and over again. The one she recounted most often was how she got up on her twelfth birthday to be told she was never returning to school and there was a job waiting for her in a Rochdale cotton mill. ‘I did cry,’ she repeated. ‘Oh, I did cry.’ She spent the last months of her life in a home. Her upright piano, and the sheet music for ‘I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles’ and ‘I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now’, went to the home with her in the hope she would play for the other residents. On arrival she declared she had never set eyes on that piano before and it most certainly was not hers. She never touched it again.

Great Aunty Margaret left school at 12 to work in the cotton mill

Some of Great-Aunty Margaret’s more personal effects, which in her handwritten, home-made will she had earmarked for particular old friends, were brought to our farm in a black bin liner for my mother to distribute. They included her fur three-quarter-length, her astrakhan coat and her engagement ring – a small flower set with diamonds.

My mother dumped the bag in Gran’s Dairy – I don’t know why, the farmhouse was big enough for umpteen bin bags – and my father mistakenly, but inevitably, dragged it out for the bin men. Within days it was flung in the dustcart and that was the end of Great-Aunty Margaret’s legacy. Mum and Dad made a mad dash to the council tip at Fleetwood to try to retrieve the bag of Great-Aunty Margaret’s treasures but arrived to find a sea of similar black plastic bags stretching to the horizon and realized the furs and diamonds were gone for ever.

As a young woman Great-Aunty Margaret had wanted a family. There was a story that she once thought she was having a baby. She got fat. She made preparations. Unfortunately she stayed pregnant for more than nine months, at which point the phantom baby faded away.

We emptied the farmhouse over many weekends during spring and summer, 2014.

It was filthy, dusty work. I dug through the dead weight of Tricia’s vinyl records and found a Roy Wood album from forty years ago and played it at full blast. ‘Look Thru the Eyes of a Fool’ crackled and slurred and jumped and blurred under the blunt needle and vibrated the stagnant air in the house just a little. As fire was cleansing, so was noise.

I found a load of washing Tricia had done months before still in the machine mouldy and rotting and loaded it straight into a bin bag.

I took photographs to remember the things we burned and to feel I was keeping a part of them: the fusty Disney picture books of Cinderella and Bambi and Alice in Wonderland from the 1970s, the disintegrating 1950s Vogue pattern for evening gloves, the handbook for a 1960s wringer, a 3d pattern for a crocheted hat that would ‘only take one hour to make’, hard-backed books with titles like Ezra the Mormon and The Major’s Candlesticks, rotting, mildewed Sunday-school prizes signed in fading ink and in a formal script ‘for Stuart, for regular attendance, 1934’. From under the stairs we dragged out half-made rag rugs from the 1950s and a romantic print of a Regency couple marked on the back ‘Christmas 1908’.