Полная версия

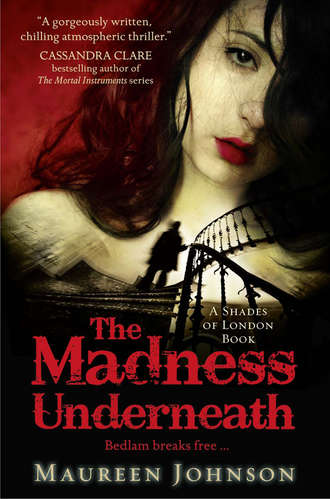

The Madness Underneath

Three times a week, I was sent to talk to Julia. And three times a week, I had to avoid talking to Julia—at least, I couldn’t talk about what had really happened to me.

You cannot tell your therapist you have been stabbed by a ghost.

You cannot tell her that you could see the ghost because you developed the ability to see dead people after choking on some beef at dinner.

If you say any of that, they will put you in a sack and take you to a room walled in bouncy rubber and you will never be allowed to touch scissors again. The situation will only get worse if you explain to your therapist that you have friends in the secret ghost police of London, and that you are really not supposed to be talking about this because some man from the government made you sign a copy of the Official Secrets Act and promise never to talk about these ghost police friends of yours. No. That won’t improve your situation at all. The therapist will add “paranoid delusions about secret government agencies” to the already quite long list of your problems, and then it will be game over for you, Crazy.

The sky was the same color as a cinder block, and I didn’t have an umbrella to protect me from the dark rain cloud that was clearly moving in our direction. I had no idea what to do with myself, now that I was actually out of the house. I saw a coffee place. That’s where I would go. I’d get a coffee, and then I’d walk home. That was a good, normal thing to do. I would do this, and then maybe . . . maybe I would do another thing.

Funny thing when you don’t get out of the house for a while—you reenter the outside world as a tourist. I stared at the people working on laptops, studying, writing things down in notebooks. I flirted with the idea of telling the guy who was making my latte, just blurting it out: “I’m the girl the Ripper attacked.” And I could whip up my shirt and show him the still-healing wound. You couldn’t fake the thing I had stretching across my torso—the long, angry line. Well, I guess you could, but you’d have to be one of those special-effects makeup people to do it. Also, people who get up to the coffee counter and whip off their shirts for the baristas usually have other problems.

I took my coffee and left quickly before I got any other funny little ideas.

God, I needed to talk to someone.

I don’t know about you, but when something happens to me—good, bad, boring, it doesn’t matter—I have to tell someone about it to make it count. There’s no point in anything happening if you can’t talk about it. And this was the biggest something of all. I ached to talk. I mean, it literally hurt me, sitting there, holding it all in hour after hour. I must have been clenching my stomach muscles the whole time, because my whole abdomen throbbed. Sometimes, if I was still awake late at night, I’d be tempted to call some anonymous crisis hotline and tell some random person my story, but I knew what would happen. They’d listen, and they’d advise me to get psychiatric help. Because my story was nuts.

The “official” story:

A man decides to terrorize London by re-creating the murders of Jack the Ripper. He kills four people, one of them, unluckily, on the green right in front of my building at school. I see this guy when sneaking back into my building that night. Because I’m a witness, he decides to target me for the last murder. He sneaks into my building on the night of the final Ripper murder and stabs me. I survive because the police get a report of a sighting of something suspicious and break into the building. The suspect flees, the police chase him, and he jumps into the Thames and dies.

The real version:

The Ripper was the ghost of a man formerly of the ghost policing squad. He targeted me because I could see ghosts. His whole aim was to get his hands on a terminus, the tool the ghost police use to destroy ghosts. The termini (there were actually three of them) were diamonds. When you ran an electrical current through them, they destroyed ghosts. Stephen had wired them into the hollow bodies of cell phones, using the batteries to power the charge. I survived that night because Jo, another ghost, grabbed a terminus out of my hand and destroyed the Ripper—and, in the process, herself.

The only people who really knew the whole story were Stephen, Callum, and Boo, and I was never allowed to talk to them again. That was one of the conditions when I left London. A man from the government really had made me sign the Official Secrets Act. Measures had been taken to make sure I couldn’t reach out to them. While I was in the hospital after the attack, knocked out cold, someone took my phone and wiped it clean.

Keep quiet, they said.

Just get on with your life, they said.

So now I was here, in Bristol, sitting around in the rented house that my parents lived in. It was a nice enough little house, high up on a rise, with a good view of the city. It had rental house furnishings, straight out of a catalog. White walls and neutral colors. A non-place, good for recuperating. No ghosts. No explosions. Just television and rain and lots of sleep and screwing around on the Internet. My life went nowhere here, and that was fine. I’d had enough excitement. I just had to try to forget, to embrace the boredom, to let it go.

I walked along the waterside. The mist dropped layer upon delicate layer of moisture into my clothes and hair, slowly chilling me and weighing me down. Nothing to do but walk today. I would walk and walk. Maybe I would walk right down the river into another town. Maybe I would walk all the way to the ocean. Maybe I would swim home.

I was so preoccupied in my wallowing that I almost walked right past him, but something about the suit must have caught my attention. The cut of the suit . . . something was strange about it. I’m not an expert on suits, but this one was somehow different, a very drab gray with a narrow lapel. And the collar. The collar was odd. He wore horn-rim glasses, and his hair was very short, but with square sideburns. Everything was just a centimeter or two off, all the little data points that tell you someone isn’t quite right.

He was a ghost.

My ability to see ghosts, my “sight,” was the result of two elements: I had the innate ability, and I’d had a brush with death at the right time. It was not magic. It was not supernatural. It was, as Stephen liked to put it, the “ability to recognize and interact with the vestigial energy of an otherwise deceased person, one who continues to exist in a spectrum usually not perceived by humans.” Stephen actually talked like that.

What it meant was simply this: some people, when they die, don’t entirely eject from this world. Something goes wrong in the death process, like when you try to shut down a computer and it goes into a confused spiral. These unlucky people remain on some plane of existence that intersects with the one we inhabit. Most of them are weak, barely able to interact with our physical world. Some are a bit stronger. And lucky people like me can see them, and talk to them, and touch them.

This is why in my many, many hours of watching shows about ghost hunters (I’d watched a lot of television in Bristol) I’d gotten so angry. Not only were the shows stupid and obviously phony, but they didn’t even make sense. These people would rock up to houses with their weird night-vision camera hats and cold-spot-o-meters, set up cameras, and then turn off all the lights and wait until dark. (Because apparently ghosts care if the lights are on or off and if it’s day or night.) And then, these champions would fumble around in the dark, saying, “IF SPIRITS ARE HERE, MAKE YOURSELVES KNOWN, SPIRITS.” This is roughly equivalent to a tourist bus stopping in the middle of a foreign city and all of the tourists getting out in their funny hats with their video cameras and saying, “We are here! Dance for us, natives of this place! We wish to film you!” And, of course, nothing happens. Then there’s always a bump in the background, some normal creaking of a step or something, and they amplify that about ten million times, claim they’ve found evidence of paranormal activity, and kick off for a cold, self-congratulatory brew.

I edged around for a few minutes, taking him in from a few different angles, making sure I knew what I was looking at. I wondered what the chances were that the first time I came out and walked around Bristol on my own, I’d see a ghost. Judging from what was going on right now, those chances were very good. A hundred percent, in fact. It made a kind of sense that I’d find one here. I was walking along a river and, as Stephen had explained to me once, waterways have a long history of death. Ships sink and people jump into rivers. Rivers and ghosts go together.

I crossed in front of him, pretending to talk on my phone. He had a blank stare on his face, the stare of someone who truly had nothing to do but just exist. I stared right at him. Most people, when stared at, stare back. Because staring is weird. But ghosts are used to people looking right through them. As I suspected, he didn’t react in any way to my staring. There was a grayness, a loneliness about him that was palpable. Unseen, unheard, unloved. He was still existing, but for no reason.

Definitely a ghost.

It occurred to me, he could have a friend. He could have someone to share this existence with. Something welled up in me, a great feeling of warmth, of generosity, a swelling of the spirit. I could share something with him, and in return, he could help me as well. Whoever this guy was, I could tell him the truth. He was part of the truth. No, he didn’t know me, but that hardly mattered. He was about to get to know me. We would be friends. Oh, yes. We would be friends. We were meant to be together. For the first time in weeks, there was a path—a logical, clear, walkable path. And it started with me sitting on the bench.

“Hi,” I said.

He didn’t turn.

“Hi,” I said again. “Yes, I’m talking to you. On the bench. Here. With me. Can you hear me?”

He turned to look at me, his eyes wide in surprise.

“Bet you’re surprised,” I said, smiling. “I know. It’s weird. But I can see you. My name’s Rory. What’s yours?”

No answer. Just a wide, eternal stare.

“I’m new here,” I said. “To Bristol. I was in London. I’m from America, but I guess you can tell that from my accent? I came here to go to school, and—”

The man bolted from his seat. Ghosts have a fluidity of movement that the living don’t know—they remain solid, yet they can move like air. I didn’t want him to go, so I bounced up and reached as far as I could to catch his coat. The second I made contact, I felt my fingers getting pulled into his body, like I had put them into the suction end of a vacuum. I felt the ripple of energy going up my arm, the inexorable force linking us both together now, then the rush of air, far greater than any waterside breeze. Then came the flash of light and the unsettling floral smell.

And he was gone.

But no. It was me.

I walked home, an entirely uphill walk in every way, feeling queasy and shaky. Once there, I went to the “conservatory,” which was really just a glassed-in porch. I sat with my head resting on my knees and replayed the scene again and again in my head. The inevitable rain came and tapped on the roof, rolling down the panes of glass.

I’d tried to make a new friend, and I had blown him up.

I’d been told to keep quiet, and I had. But it wasn’t going to work anymore. I needed Stephen, Callum, and Boo again. I needed them to know what was going on with me. I had made a few efforts to find them in the last week. Nothing serious—I’d just tried to find profiles on social networking sites. No matches. This much I expected.

Today I was going to try a bit harder. I Googled each of their names. I found one set of links that were definitely about Callum. Callum had mentioned that he was good at football. What he didn’t say was that he had been a member of the Arsenal Under-16s, a premier-level junior club. He’d been in training to become a professional footballer. And all of that ended one day when he was fifteen, when a malicious ghost let a live wire drop into the puddle Callum was stepping through. He survived the electrocution and recovered, but something in him was never the same. Whether it was physical or psychological, who knew, but he couldn’t play football anymore. The magic was gone. Callum hated ghosts. He wanted them to burn.

In terms of contact information, though, there was nothing.

I moved on to Boo, Bhuvana Chodhari. Boo had been sent into Wexford as my roommate after I saw the Ripper. It was her first job with the squad. There were a lot of Chodharis in London, and even quite a few Bhuvana Chodharis. I knew Boo had been in a serious car accident, but I found nothing about it. Nothing about Boo at all, really. That surprised me. Of the three of them, I expected her to pop up somewhere. But I guess once you joined the squad, your Facebook days were over.

I searched for Stephen last. In terms of his past, I knew very little. I think he said once he was from Kent, but Kent was a big place. He went to Eton. He had been on the rowing team while he was there. I started with that, and managed to come up with one photo of a rowing team in which I could clearly see him in the back. He was one of the tallest, with dark hair and eyes fixed at the camera. He was one of the not-smiling ones. In fact, he was the least-smiling person in the photo. Like everyone else, he had his arms folded over his chest, but he seemed to mean it.

But again, there was nothing in terms of how to make contact.

I stared at the photo of Stephen for a long time, then at the ceiling of the conservatory, which was thick with condensation and fat drops of water. I knew that Stephen and Callum shared a flat on a small street in London called Goodwin’s Court. I’d been there. I had never, however, looked at the building number. The few times I’d been there, I was following someone to the door, usually in a state of distress.

I pulled up a map and some images of the street. The trouble with Goodwin’s Court was that it was very picturesque, and very small, and all of it looked more or less the same. The houses were all quite dark, with dark brick and black trim, so it was hard to see numbers. I found one pretty grainy picture that I thought was probably their house, but I couldn’t see the number.

My phone rang. It was Jerome. He often called me on his break between classes. Jerome had been what I suppose I could call my “make-out buddy” at Wexford. But since I’d been gone, we had become something much more. I still couldn’t talk to him the way I needed to talk to someone, but it was nice that I had someone in theory. An imaginary boyfriend I never saw. We were planning to see each other over the Christmas break in a few weeks, probably only for a day, but still. It was something.

“Hey, disgusting,” he said.

Jerome and I had developed a code for expressing whatever it was we felt for each other. Instead of saying “I like you” or whatever mush expresses that sentiment, we had started saying mildly insulting things. Our entire correspondence was a string of heartfelt insults.

“What’s wrong?”

“Nothing,” I said quickly. “Nothing.”

“You sound funny.”

“You look funny,” I replied.

I could hear Wexford noises in the background. Not that Wexford noises were so particular. It was just noise. People. Voices. Guys’ voices.

He was talking quickly, telling me a story about some guy in his building who’d been busted for claiming to have an interview at a university, but actually he went off to see his girlfriend in Spain, and how someone had ratted him out to Jerome, and Jerome had the unwelcome task of reporting him. Or something.

I was only half listening. I rubbed at my legs and stared at the images of Goodwin’s Court. I hadn’t shaved in three weeks, so that was quite a situation I had going. For the first few days, I hadn’t been able to bend over completely or get the injured area wet, so I couldn’t shave. The hairs sprouted, and they were kind of cute. So I just let them go to see what would happen, and what had happened was that I had a fine web of delicate hair all over my legs that I could ruffle while I watched television, like some people absently pet their cats. I was my very own fuzzy pet.

The grainy picture told me nothing.

“Hello?” Jerome said.

“I’m listening,” I lied. I guess the story had finished.

“I have to go,” he said. “You’re disgusting. I want you to know that.”

“I heard they named a mold after you,” I replied. “Poor mold.”

“Vile.”

“Gross.”

After I hung up, I pulled the computer closer to stare at the image. I moved the view up and down the row of tiny, dark houses with their expensive gaslights and security system warning signs. Up and down. And then I saw something. There was a tiny plaque on the outside of one of the houses, right above the buzzer. That plaque. I knew it. That was their building. There was some kind of a small company downstairs, a graphic designer or photographer or something like that. The print was impossible to make out in the photo, but it began with a Z. I knew that much. Zoomba, Zoo . . . Zo . . . something.

It was a start, enough to search the Internet. I tried every combination I could with Z and design and art and photography and graphic design. It took a while, but I eventually hit it. Zuoko. Zuoko Graphics. With a phone number. I pulled up the address in maps, and sure enough, it was the same building.

Now all I had to do was call and ask them . . . something. Get them to go upstairs. Leave a note. I would say it was an emergency and that they needed to call Rory, and I would leave my number. So simple, so clever.

So I called, and Zuoko Graphics answered. Well, some woman did. Not the entire agency.

“Hi,” I said. “I’m trying to reach someone else in this building. It’s kind of an emergency. Sorry to bug you. But there are some guys? Who live upstairs? From you?”

“Two guys, right?” the woman said. “About nineteen or twenty?”

“That’s them,” I said.

“They moved out, about a week and a half ago.”

“Oh . . .”

“You said it’s an emergency? Do you have another way of reaching them, or—”

“It’s okay,” I said. “Thanks.”

So that was that. I struck that off the list. They’d moved out. Because of me? Because I knew where they lived? Maybe they were really cleaning up their tracks so they could never be found again.

I heard someone come into the house. I quickly clicked on a link to BBC news and pretended to be deeply engrossed in world affairs. My mom came into the kitchen.

“We have chairs,” she said.

“I like it down here. It’s where I belong.”

“Doing some work?” she asked.

My parents weren’t stupid. They knew I hadn’t really been keeping up with school stuff, but they hadn’t been pressuring me. I was recovering. Everyone was very gentle with me. Soft voices. Food on demand. Command of the remote control. But there was just a little lilt of hope in her voice, and I hated to disappoint her.

“Yup,” I lied.

“I just got a call from Julia. She’s asking all of us to come in tomorrow for a group session. Is that all right with you?”

I ran my thumbs along the bottom edge of my computer. This wasn’t right. We didn’t do group sessions. Was this an intervention? It sounded like an intervention, at least like the ones I had seen on TV. They get your family and a psychologist, and they sit you in a room and tell you that the game is up, you have to change. Change or die. Except . . . I didn’t drink or do drugs, so I wasn’t sure what they could intervene about. You can’t stop someone from doing nothing all time.

I thought about the man again . . . my hand reaching out in greeting. Maybe the first greeting he’d had in years. The hand that wiped him from existence. Or something.

“Sure,” I said, slightly dazed. “Whatever.”

The next day at noon, the three of us waited by Julia’s door, staring down at the little smoke-detector-shaped noise-reduction devices that lined the hallway. That’s how you could tell a therapist was behind the door. One of these little privacy devices would spring up naturally, like a mushroom after a rainstorm.

“So,” Julia said, once we were all squeezed onto her sofa, “I want to talk to all of you about the progress we’ve made, and just a little bit about the process. Recovering from a trauma like this. There’s no one method that fits everyone. I want you to know, and I want you to hear this, Rory . . . I think Rory is very, very strong. I think she’s resilient and capable.”

It was supposed to make me feel good, but I burned . . . burned with anger or embarrassment or resentment. I felt my cheeks flush. This was the worst of it. Right now, this. I’d survived the stabbing. I’d survived all of the other, much crazier stuff. But now I was a victim. I might as well have had the word tattooed on my face. And victims get strange looks and psychologists. Victims have to sit between their parents while they’re told how “resilient” they are.

“In my opinion, I feel . . . very strongly . . . that Rory should be returned to Wexford.”

I seriously almost fell off the sofa.

“I’m sorry?” my mother said. “You think she should go back?”

“I realize what I’m saying may run counter to all your instincts,” Julia said, “but let me explain. When someone survives a violent assault, a measure of control is taken away. In therapy, we aim to give victims back their sense of control over their own lives. Rory’s been removed from her school, taken away from her friends, taken out of her routine, out of her academic life. I believe she needs to return. Her life belongs to her, and we can’t let her attacker take that away.”

My dad had a look in his eye that I’d once seen in a painting at the National Gallery. It was of a man who was facing down an angel that had just come crashing through his ceiling and was now glowing expectantly in the corner of the room. A surprised look.

“I say this with full understanding that the idea may be difficult for all of you,” she continued, mostly to my parents. “If you decide against this, that’s absolutely fine. But I feel the need to tell you this . . . Rory and I have done quite a lot of work in our sessions. I’m not saying we’ve done all we can do. I’m saying the next logical step is to get her back into a normal routine.”

She was lying. Julia, right now, was lying. And she was looking right at me, as if challenging me to contradict her. We both knew perfectly well that I’d told her nothing at all. Why the hell would Julia lie? Had I said things without even realizing it?

“She can have a normal routine here,” my mom said.

“It’s not her normal routine. It’s a new routine based around the attack. Right now, keeping her away from the learning environment is punitive. I’m not talking about sending Rory out to live in a wild and dangerous environment—this is a structured one, with everything in place to allow her to resume her life.”

“An environment where she was stabbed,” my dad said.

“Very true. But that particular case was a true anomaly. You need to separate your fears from the actual risk involved. What happened will not be repeated. The attacker is deceased.”