Полная версия

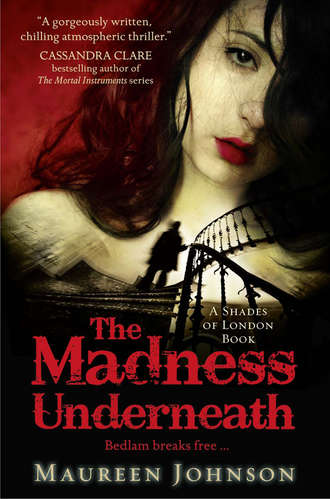

The Madness Underneath

For my friend, the real Alexander Newman, who would never let a tiny thing like having twelve strokes get the better of him. When I grow up, I want to be you. (Maybe without the twelve strokes? You know what I mean.)

Contents

Dedication

The Royal Gunpowder Pub, Artillery Lane, East London November 11 10:15 A.M.

The Crack in the Floor

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

New Dawn Psychic Parlor, East London December 9 11:47 P.M.

The Falling Woman

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

THE ROYAL GUNPOWDER PUB, ARTILLERY LANE, EAST LONDON NOVEMBER 11 10:15 A.M.

Charlie switched on the television. The television in the Royal Gunpowder went on for only two things: when Liverpool played and Morning with Michael and Alice, the relentlessly cheerful talk show. Charlie liked to watch this as he prepared for the day, particularly the cooking part. They always made something good, and for some reason, this made him enjoy his bacon sandwich even more. Today, they were making a roast chicken. His barman, Sam, came up from the basement with a box of tonic water. He set it on the bar and quietly got on with his work, taking the chairs from their upside-down positions on the tables and setting them upright on the floor. Sam was good to have around in the mornings. He didn’t say much, but he was still good company. He was happy to be employed, and it always showed.

“Good-looking chicken, that,” he said to Sam, pointing to the television.

Sam paused his work to look.

“I like mine fried,” Sam said.

“It’ll kill you, all that fried food.”

“Says the man eating the bacon sarnie.”

“Nothing wrong with bacon,” Charlie said, smiling.

Sam shook his head good-naturedly and continued moving chairs. “Think we’ll get more of them Ripper freaks today?” he asked.

“Let’s hope so. God bless the Ripper. We did almost three thousand pounds last night. Speaking of, they do eat a lot of crisps. Get us another box of the plain and”—he sorted through the selection under the bar—“cheese and onion. And some more nuts while you’re there. They like nuts as well. Nuts for the nutters, eh?”

Without a word, Sam stopped what he was doing and returned to the basement. Charlie’s gaze was fixed on the television and the final, critical stages of the cooking segment. The cooked chicken was produced from the oven, golden brown and lovely. The show moved on to the next segment, talking about some music festival that was going on in London over the weekend. This interested Charlie less than the chicken, but he watched it anyway since he had a cigarette to finish. When he was down to the filter, he stubbed it out and got to work.

He had just started wiping down the blackboard to write the day’s specials when he heard the sound of breaking glass from below. He opened the basement door.

“Sam! What in God’s name—”

“Charlie! Get down here!”

“What’s the matter?” Charlie yelled back.

Sam did not reply.

Charlie swore under his breath, allowed himself one heavy post-smoke cough, and headed down the stairs. The basement stairs were narrow and steep, and the basement itself was full of things Charlie largely didn’t want to deal with—broken chairs and tables, heavy crates of supplies, racks of glasses ready to replace the ones that were chipped, cracked, or stolen every day.

“Sam?” he called.

“In here!”

Sam’s voice was coming from a small room off the main one. Charlie ducked down. The ceiling was lower in this room; it just skimmed his head. Many times he had almost knocked himself senseless on it.

Sam was near the wall, cowering between two shelving units. There were two shattered pint glasses, as well as a roughly drawn X in chalk on the stone floor.

“What are you playing at, Sam?”

“I didn’t do that,” Sam replied. “Those weren’t there a few minutes ago.”

“Are you feeling all right?”

“I’m telling you, those weren’t there.”

This was not good, not good at all. The glasses clearly hadn’t fallen off a shelf—they were in the middle of the room. The X was shaky, like the hand that had drawn it could barely hold the chalk. No one looked healthy in the basement’s faintly greenish fluorescent light, but Sam looked particularly bad. The color had drained from his face, and he was quivering and glistening with sweat.

Maybe this had been bound to happen. Charlie had always known the risks, but the risks were part of the agreement. He had gotten sober, and he trusted that others could as well. And you needed to show that trust.

Charlie said quietly, “If you’ve been taking something—”

“I haven’t!”

“But if you have, you just need to tell me.”

“I swear to you,” Sam said, “I haven’t.”

“Sam, there’s no shame in it. Sobriety is a process.”

“I didn’t take anything, and I didn’t do that!”

There was an urgency in Sam’s voice that frightened Charlie, and he was not a man who frightened easily. He’d been through fights, withdrawal, divorce. He faced alcohol, his personal demon, every day. Yet, something in this room, something in the sight of Sam huddled against the wall and this crude X and broken glass on the floor . . . something in this unnerved him.

There was no point in checking to see if anyone else was down here. Every business in the area had fortified itself when the Ripper was around. The Royal Gunpowder was secure.

Charlie bent down and ran his hand over the cool stone floor.

“How about we just get rid of this,” he said, wiping away the chalked X with his hand. In cases like this, it was best to calmly get things back to normal and sit down and talk the issue through. “Come on, now. We’ll go upstairs and have a cup of tea, and we’ll talk this out.”

Sam took a few tentative steps from the wall.

“Good, that’s right. Now let’s just get rid of this and we’ll have a nice cuppa, you and me . . .”

Charlie continued wiping away the last of the X. He didn’t see the hammer.

The hammer was used to pry open crates, to knock sticky valves into action, and to do quick repairs on the often unstable shelving units. Now it rose, lingering just long enough over Charlie’s head to find its mark.

“No!” Sam screamed.

Charlie turned his head in time to see the hammer come down. The first time it did so, Charlie remained upright. He made a noise—not quite a word, more of a broken, gurgling sound. There was a second blow, and a third. Charlie was still upright, but twitching, struggling against the onslaught. The fourth blow seemed to do the most damage. An audible cracking sound could be heard. On that fourth blow, Charlie fell forward and did not move again.

The hammer clattered to the ground.

Out flew the web and floated wide;

The mirror crack’d from side to side;

“The curse is come upon me,” cried

The Lady of Shalott.

—Alfred Lord Tennyson,

“The Lady of Shalott”

I didn’t think hockey had trained me for anything in life until I went to therapy.

“So,” Julia said.

Julia was my therapist. She was Scottish and petite and had a shock of white-blond hair. She was probably in her fifties, but the lines in her face were imperceptible. She was a careful person, well spoken, so achingly professional it actually made me itch. She didn’t fuss around in her chair or need to change over and cross the other leg. She just sat there, calm as a monk. The winds might blow and the rains might fall, but Julia would remain in the same position in her ergonomic chair and wait it out.

The clock in Julia’s office was hidden in plain sight; she put it behind the chair where her patients sat, on top of a bookcase. I followed the clock by watching its reflection in the window, watching time run backward. I had just managed to waste a solid forty-five minutes talking about my grandmother—a new record for me. But I’d run out of steam, and the silence descended on the room like a vague but ever-intensifying smell. There was a lot going on behind her never-blinking eyes. I could tell, from what now amounted to hours of staring at her, that Julia was studying me even more carefully than I was studying her.

And I knew about her relationship with that clock. All she had to do was flick her eyes just a tiny bit to the left, and she could see both me and the time without moving her head. It was an incredibly small move, but I had started to look for it. When Julia checked the time, it meant she was about to do something.

Flick.

Time to get ready. Julia was going to make a move. The ball was heading for my face. Time to dodge.

“Rory, I want you to think back for me . . .”

Dive! Dive!

“. . . we all learn about death somehow. I want you to try to remember. How did you learn?”

I had to restrain myself. It doesn’t look good if your therapist asks you how you learned about death and you practically jump off the couch in excitement because that’s pretty much your favorite story ever. But as it happens, I have a really good “learning about death” story.

I wasted about a full minute, grinding away the airtime, tilting my head back and forth. It’s hard to pretend to think. Thinking doesn’t have an action stance. And I suspected that my “thinking” face looked a lot like my “I’m dizzy and may throw up” face.

“I was ten, I guess. We went to Mrs. Haverty’s house. She lived in Magnolia Hall. Magnolia Hall is this big heritage site, proper antebellum South, Gone with the Wind, look-at-how-things-were-before-the-War-of-Northern-Aggression sort of place. It has columns and shutters and about a hundred magnolia trees. Have you ever seen Gone with the Wind ?”

“A long time ago.”

“Well, it looks like that. It’s where tourists go. It’s on a lot of brochures. Everything about it looks like it’s from 1860 or something. And no one ever sees Mrs. Haverty, because she’s crazy old. Like, maybe she was born in 1860.”

“So an elderly woman in a historical house,” she said.

“Right. I was in Girl Scouts. I was a really bad Girl Scout. I never got any badges, and I forgot my troop number. But once a year there was this amazing picnic thing at Magnolia Hall. Mrs. Haverty let the Girl Scouts use the grounds, because apparently she had been a Girl Scout back when the rocks were young and the atmosphere was forming . . .”

Julia eyed me curiously. I shouldn’t have thrown in that little flourish. I’d told this story so many times that I’d refined it, given it nice little touches. My family loves it. I pull it out every year at our awkward get-together dinners at Big Jim’s or at my grandmother’s house. It’s my go-to story.

“So,” I said, slowing down, “she’d have barbecues set up, and huge coolers of soda, and ice cream. There was a massive Slip ’N Slide, and a bouncy castle. Basically, it was the best day of the year. I pretty much only did Girl Scouts so I could come to this. So this one summer, when I was ten, I guess . . . oh, I said that . . .”

“It’s all right.”

“Okay. Well, it was hot. Like, real hot. Louisiana hot. Like, over a hundred hot.”

“Hot,” Julia summarized.

“Right. Thing was, Mrs. Haverty never came out, and no one was allowed inside. She was kind of legendary. We always wondered if she was looking at us from the window or something. She was like our own personal Boo Radley. Afterward, we would always make her a huge banner where we’d write our names and thank her and draw pictures, and one of the troop leaders would drive it over. I don’t know if Mrs. Haverty let her in or if she just had to throw it out of the car window at the porch. Anyway, usually the Girl Scouts got Porta Potties for the picnic. But this year there was some kind of strike at the Porta Potti place and they couldn’t rent any, and for a week or so, they thought there was going to be no picnic, but then Mrs. Haverty said it was okay for us to use the downstairs bathroom, which was a really big deal. On the bus ride over, they gave us all a lecture on how to behave. One person at a time. No running. No yelling. Right to the bathroom and back out again. We were all excited and sort of freaked out that we could actually go inside. I made up my mind I was going to be the first person in. I was going to pee first if it killed me. So I drank an entire bottle of water on the ride—a big one. I made sure our troop leader, Mrs. Fletcher, saw me. I even made sure she said something to me about not wasting my water. But I was determined.”

I don’t know if this happens to you, but when I get talking about a place, all the details come back to me at once. I remember our bus going up the long drive, under the canopy of trees. I remember Jenny Savile sitting next to me, stinking of peanut butter for some reason and making an annoying clicking noise with her tongue. I remember my friend Erin just staring out the window and listening to something on her headphones, not paying any attention. Everyone else was looking at the crew that was inflating the bouncy castle. But I was on high alert, watching the house get closer, getting that first view of the columns and the grand porch. I was on a mission. I was going to be the first to pee in Magnolia Hall.

“My Scout leader was probably on to me,” I continued, “because I had a reputation for being that girl—not the leader or the baddest or the prettiest, or whatever that girl is. I was that girl who always had some little idea, some bone to pick or personal quest, and I would not be stopped until I had settled the matter. And if I was gulping water and bouncing in my seat, claiming extreme need of the bathroom, she knew I was not going to shut up until I was taken inside of Magnolia Hall.”

Julia couldn’t conceal the whisper of a smile that stole across her lips. Clearly, she had picked up on this aspect of my personality.

“When we pulled up,” I went on, “she said, ‘Come on, Rory.’ There was a real bite in how she said my name. I remember it scared me.”

“Scared you?”

“Because the Scout leaders never really got mad at us,” I explained. “It wasn’t part of their jobs. Your parents got mad at you, and maybe your teachers. But it was weird to have another adult be mad at me.”

“Did it stop you?”

“No,” I said. “I’d had a lot of water.”

“Let me ask you this,” Julia said. “Why do you think you behaved that way? Why did it matter so much to you to be the first one to use the toilet?”

This was something so obvious to me that I had no mechanism to explain it. I had to be first to that bathroom for the same reason that people climb mountains or go to the bottom of the sea. Because it was new and uncharted territory. Because being first meant . . . being first.

“No one had ever seen the inside of her house,” I said.

“But it was just a toilet. And you said this was a behavior you were aware of in yourself. That you come up with plans, ideas.”

“They’re usually bad plans,” I clarified.

Julia nodded slightly and wrote a note in her pad. I’d given her a clue about my personality. I hated when that happened. I refocused on the story. I remembered the heat. Heat—real heat—was something I hadn’t felt in England since I’d arrived. Louisiana summer heat has a personality, a weight to it. It wraps you entirely in its sweaty embrace. It goes inside of you. Magnolia Hall had never known an air conditioner. It was like an oven that had been on for a hundred years, and it felt entirely possible that some of the air trapped in there had been there since the Civil War, blown in during a battle and locked away for safekeeping.

I can always remember my first step through that doorway, that slap of dust-stinking heat. The stillness. The entrance hall with the genuine family portraits, the marble-topped table with a bowl of parched and drooping azaleas, the hoarded stacks of old newspapers in the corner. The bathroom was in an alcove under the stairs. Mrs. Fletcher had to supervise the unloading of the bus and make sure Melissa Murphy had her EpiPen in case she was stung by a bee, so she told me to come right out when I was done and not to touch anything. Just go to the bathroom and leave.

“I was in there by myself,” I said. “The first person ever . . . I mean, first person that I knew, so I couldn’t not look around. I only looked in rooms with open doorways. I didn’t snoop. I just had to look. And there was this dog in the middle of one of the sitting rooms in the front, a big golden retriever . . . and I like dogs. A lot. So I petted him. I didn’t even hear Mrs. Haverty come in. I just turned around and there she was. I guess I expected her to be in a hoop skirt or covered in spiderwebs or something, but she was wearing one of those sportswear things that actual senior citizens wear, pink plaid culottes and a matching T-shirt. She was incredibly pale, and she had all these varicose veins—her calves had so many blue lines on them, she looked like a road map. I thought I’d been caught. I thought, ‘This is it. This is when I get killed.’ I was so busted. But she just smiled and said, ‘That’s Big Bobby. Wasn’t he beautiful?’ And I said, ‘Was?’ And she said, ‘Oh, he’s stuffed, dear. Bobby died four years ago. But he liked to sleep in here, so that’s where I keep him.’”

It took Julia a moment to realize that that was the end of the story.

“You’d been petting a stuffed dog?” she said. “A dead one?”

“It was a really well stuffed dog,” I clarified. “I have seen some bad taxidermy. This was top-notch work. It would have fooled anyone.”

A rare moment of sunlight came in through the window and illuminated Julia’s face. She was giving me a long and penetrating stare, one that didn’t quite go through me. It got about halfway inside and roamed around, pawing inquisitively.

“You know, Rory,” she said, “this is our sixth meeting, and we really haven’t talked about the reason why you’re here.”

Whenever she said something like that, I felt a twinge in my abdomen. The wound had closed and was basically healed. The bandages were off, revealing the long cut and the new, angry red skin that bound the edges together. I searched my mind for something to say, something that would get us off-roading again, but Julia put up her hand preemptively. She knew. So I kept quiet for a moment and discovered my real thinking face. I could see it, but I could tell it looked pained. I kept pursing and biting my lips, and the furrow between my eyes was probably deep enough to hold my phone.

“Can I ask you something?” I finally said.

“Of course.”

“Am I allowed to be fine?”

“Of course you are. That’s our goal. But it’s also all right not to be fine. The simple fact of the matter is, you’ve had a trauma.”

“But don’t people get over traumas?”

“They do. With help.”

“Can’t people get over traumas without help?” I asked.

“Of course, but—”

“I’m just saying,” I said, more insistently, “is it possible that I’m actually okay?”

“Do you feel okay, Rory?”

“I just want to go back to school.”

“You want to go back?” she asked, her brogue flicking up to a particularly inquisitive point. You want tae go back?

Wexford leapt into my mind, like a painted backdrop on a suddenly slackened rope crashing down onto a stage. I saw Hawthorne, my building, looking like the Victorian relic that it was. The brown stone. The surprisingly large, high windows. The word WOMEN carved over the door. I imagined being in my room with Jazza, my roommate, at nighttime, when she and I would talk across the darkness from our respective beds. The ceilings in our building were high, and I’d watch passing shadows from the London streets and hear the noise outside, the gentle clang and whistle of the heaters as they gave the last blast of heat for the night.

My mind flashed to a time in the library, when Jerome and I were together in one of the study rooms, making out against the wall. And then I flashed somewhere else. I pictured myself in the flat on Goodwin’s Court with Stephen and Callum and Boo—

“We’re at time for today,” she said, her eye flicking toward the clock. “We can talk about this some more on Friday.”

I snatched my coat from the back of the chair and got it on as quickly as possible. Julia opened the door and looked out into the hall. She turned back to me in surprise.

“You came by yourself today? That’s very good. I’m glad.”

Today, my parents had let me come to therapy by myself. This was what passed for excitement in my life now.

“We’re getting there, Rory,” she said. “We’re getting there.”

She was lying. I guess we all have to lie sometimes. I was about to do the same.

“Yeah,” I said, stretching my fingers into the tips of my gloves. “Definitely.”

I like to talk. Talking is kind of my thing. If talking had been a sport option at Wexford, I would have been captain. But sports always have to involve running, jumping, or swinging your arms around. You don’t get PE points for the smooth and rapid movement of the jaw.