Полная версия

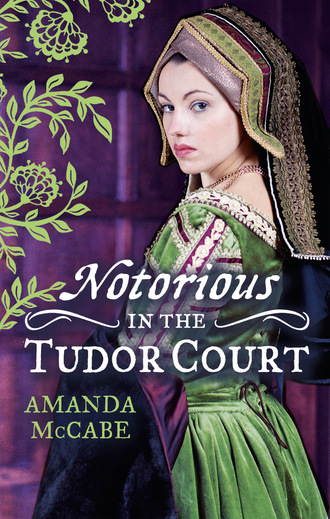

NOTORIOUS in the Tudor Court

Claudine’s maid was putting the finishing touches to her gingery red hair, lowering a stiffened gold headdress into place. Marguerite’s own headdress was the newer, lighter nimbus shape, of green velvet trimmed with pearls, her silvery hair falling free down her back under the short, sheer gold veil.

Claudine’s gaze narrowed when she saw Marguerite in her fine raiment. “How very youthful you look, Mademoiselle Dumas,” she muttered.

“Merci,” Marguerite answered lightly, smoothing down her sleeves. “I am sure we will all put the English and their rustic garments to shame!”

“And especially the Spanish,” Claudine’s husband, the Comte de Calonne, said, as he came into the room with his own richly clad attendants. “Michel tells me they are all in black, like a flock of crows!”

Everyone laughed, and fell into their places to be led into the English queen’s presence. There could be no Spanish jests there, naturellement!

Marguerite did not know what she expected of this lady, who had been daughter to the legendary Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, Queen of England for nearly twenty years. A lady renowned for her piety and great learning, beloved by her subjects. A woman who, as aunt to the Emperor Charles, stood in the way of France’s interests on these shores.

Yet she did not look so formidable as she greeted them with a gracious smile, a few polite words in perfect French. She looked like a settled, contented matron of middle years, not very tall, stout from a plethora of pregnancies that had only produced one living child, Princess Mary. Her once fair hair was liberally streaked with grey, drawn back under a peaked pearl cap and gauze veil. She wore a fine gown of red-and-black figured brocade, flashing ruby jewels and a pearl-encrusted cross, yet all the finery did not conceal the deep lines of worry and care on her round face.

She took them all in with a sweeping glance of her dark eyes. “How very kind you are, Bishop Grammont, to relieve our winter doldrums with your presence!” she said, holding out a be-ringed hand for Grammont’s salute. “We have a great deal of merriment planned for your stay.”

“We thank your Majesty for such a gracious welcome,” the bishop answered. “Our two nations are united, as ever, in the warmest bonds of friendship.”

After a few more pleasantries, Grammont offered Katherine his arm, and they led the whole party along a gallery hung with tapestries of the story of David, lit on their way by green-and-white clad pages bearing torches.

“May I escort you, Mademoiselle Dumas?” a quiet voice asked, as Marguerite moved to take her place behind Claudine.

She turned sharply to find Father Pierre LeBeque standing close, his arm in its black woollen sleeve politely extended. His eyes glowed in the dim light, and he watched her with a tense expectation.

Marguerite glanced hastily around, but there was no one to come to her rescue. At any second it would be their turn to move forward, and she could not fall behind.

She nodded, and placed her hand lightly on his arm. It was coiled beneath her touch, stiff and bony. Was he frightened of something, then, to be so tense?

She had little time to ponder the oddities of Father Pierre. The long gallery opened to a vast banquet hall, where it seemed all the world waited in glittering array.

For a moment, her eyes were dazzled. This must be an enchanted kingdom, like in tales her father told her when she was a child! A land of gods and goddesses, powerful witches and princesses, not the stolid red-brick English world she saw outside. Roger Tilney had told her this space was newly built for this meeting, at vast dimensions of one hundred feet long and thirty feet wide, and she well believed it. The walls and floor were painted to look like marble, with gilded mouldings, the low, timbered ceiling covered with red buckram and embroidered with roses and pomegranates. Tiered buffets lined the walls, displaying a vast amount of gold plate. Bright banners hung from the ceiling.

And the people were clad in such sparkling raiment they added to the golden dazzlement. Many of the Spanish were in black, or wine red or burnt amber, but they served as an outline, a counterpoint to the English in their violet purple, silver tissue, sky blue, vivid rose, tawny and turquoise and sunny yellow.

And, at the end of the room, rose a triumphal arch painted with a large scene of—non! It could not be.

But it was. A painting of Henry’s long-ago victory over the French armies at the Battle of The-rouanne.

Alors! That was not so very diplomatic of the English king. Marguerite’s dazzlement faded into cold clarity. That audacious scene was just the reminder she needed of why she was really here. Why they were all here. To protect France from just such another defeat.

“Welcome, welcome!” a stentorious voice boomed, soaring above the hum of laughter and conversation. All other voices echoed away, and the crowd parted. “Bishop Grammont, for the great love we bear our brother King François, welcome to our Court.”

And the king himself appeared, for it could be none but the legendary Henry. He leaped down from a dais set up beneath the arch, a tall, broad-shouldered, barrel-chested figure swathed in cloth of gold trimmed with ermine and diamonds. He, unlike the queen, was just what Marguerite imagined. His redgold hair cut short in the French style, covered by a crimson velvet cap, his square face framed by a short beard.

He was all bluff heartiness, tremendous good cheer as he greeted the French. All lighthearted welcome. Yet Marguerite saw that his small, shining eyes missed nothing at all. They moved over her—and widened.

She gave him a deep curtsy, and he grinned at her. So, his rumoured regard for the ladies was true! But was it also true he now had attention only for Mistress Boleyn?

Which one was she? Marguerite wondered, studying the array of ladies behind the queen. She saw none there whose beauty could rival her own, but there would be time to look for Anne Boleyn later. They were shown to their seats, at a long table to the right of the hall. The Spanish were to the left, and Henry escorted Katherine back to the dais where they were seated with Grammont and Ambassador Mendoza.

The tables were spread with white damask cloths, embroidered with roses, crowns, and fleurs-de-lis; the benches where they sat were lined with soft gold velvet cushions. In the centre of the table was a golden salt cellar engraved with the initials H and K, and each place boasted a small loaf of manchet bread wrapped in a cover of embroidered linen and a tall silver goblet filled with fine Osney wine from Alsace. Servants soon appeared with great golden platters of venison, capons, partridge, lark and eels, game pie with oranges and King Henry’s favourite baked lampreys. A peacock, redressed in its own feathers, was ceremoniously presented to the king amid copious applause.

A lively song of recorders, lutes and pipes struck up from a gallery hidden behind one of the tapestries, and the conversation grew in vast waves around Marguerite. She nibbled at a piece of gingerbread painted with gold leaf, listening with half an ear as Father Pierre talked to her. All around her were the people she would have to get to know, would have to guard against and fend off, and perhaps even destroy in the end. Her first glimpse of the opposing army.

She knew she was not likely to learn much of use tonight. Everyone was on their best, most guarded behaviour, despite the flowing wine. They, too, were unsure of their surroundings. Unsure of the enemies’ real strength. In a few days, when everyone had settled into long days of delicate negotiations and longer evenings of revelry, when enmities and flirtations had both sprung to full flower, she would be better able to gauge the atmosphere. Better able to take full advantage of rivalries and passions.

Tonight she could only observe, perhaps begin to collect precious droplets of gossip.

An acrobat in motley livery and bright bells performed a series of backward flips along the aisle between the tables, followed by a gambolling troupe of dwarves and trained dogs. Pages poured more wine, carried in yet more platters of fine delicacies. Marguerite laughed at the antics, nibbled at what was put before her, yet always she watched. Watched and listened, as the voices grew louder and the laughter heartier as the night went on.

King Henry, she saw, betrayed no hint of ill will toward the queen. Indeed, he was all solicitude, making sure her goblet was full, that she had the choicest morsels of venison and capon. He laughed heartily at his fools’ jests, and listened intently when Wolsey murmured in his ear.

Princess Mary, the proposed bride of the Duc d’Orléans, sat by her mother, pale-faced and bright-haired, small for her age in her fine white brocade gown. She seemed shy and serene, speaking only to her mother, or to the Spanish ambassador in perfect Castilian Spanish.

The Spanish party across the aisle were not as raucous as the English, but neither were they so dour. They talked and jested just as everyone else did, led in conversation by a pretty woman of near Queen Katherine’s age, a lady with a ready smile and soft brown eyes. As Marguerite watched, the lady laughed gently, holding out her goblet for a man seated next to her to refill.

He leaned forward, illuminated by the rich amber glow of the candelabra. His loose, long hair, golden as the summer sun, fell forward like a curtain, and he swept it back over his shoulder in one smooth movement. His profile, sharply etched as an ancient cameo, was limned in the light.

Marguerite gasped, and shook her head hard, certain she was dreaming! That she had imbibed too much of the fine Alsatian wine and was imagining things. She squeezed her eyes tightly shut.

Yet when she opened them, he was still there. The Russian. Laughing boldly, and just as beautiful as that night in Venice. The fallen angel she had vowed to kill if ever their paths crossed again. There he was, mere steps away, in the last place she ever expected.

She banged her goblet down on the table so violently that vivid red wine splashed over its etched lip, spilling on to her fingers. Bright spots, like blood, bloomed on the white damask cloth.

“The bold cochon,” she muttered roughly.

“Are you ill, Mademoiselle Dumas?” Father Pierre asked solicitously.

Marguerite shook her head. “I am quite well, thank you. Merely tired from the journey, I think.”

“Perhaps a bit more wine will help,” he said, gesturing to one of the pages.

As the boy refilled her goblet, Marguerite surreptitiously studied Nicolai Ostrovsky. He did not appear to have noticed her yet. He sat there laughing and jesting with his companions, making sure the lady had the finest sweetmeats on her plate.

He was certainly far better dressed than in Venice! Or at least more elaborately so. Nor was the motley he wore to walk the tightrope in the Piazza San Marco in evidence. He was clad in a fine silk doublet of dark red trimmed with dull gold braid, his only jewel a single pearl in one ear, half-hidden by that shining golden hair.

What game did he play now?

She would just have to find out. Very soon, before he found her out first.

Chapter Five

The palace was quiet as Marguerite slipped out of her chamber, muffled in a hooded cloak. It was surely somewhere near morning, for the banquet and recital had gone on for long hours. And it was no easy thing to persuade hundreds of courtiers to retire! But all was silent now, almost eerily so in the purple-blackness of deepest night. The only sounds, so soft they were almost imperceptible, were the shuffles of the pages who slept on pallets outside doors, the whispers of Claudine’s maids in their truckle beds.

Marguerite crept down the narrow back stairs, lit on her way by the smoking torches set high in their sconces. She had changed her heeled brocade shoes for soft-soled leather boots and left off her cumbersome petticoats, tucking her skirts into a kirtle to keep them out of her way. Her progress was swift as she dashed down the stairs and out into the gardens.

She had bribed one of the pages into telling her where the Russian was lodged, but it was in a section of the palace off one of the other courtyards, behind the Spanish apartments. She hurried along the twisting pathways, so crowded only that afternoon but now completely deserted. Only the stars and the moon, like tiny crystals in the violet velvet of the sky, watched her progress. The darkened windows of the buildings were blank, turning away from her actions as they had so many others in the past. The doings of humans were swiftly gone, those windows seemed to say, and of no interest at all. Only bricks and mortar, and the river beyond, were eternal.

Or perhaps it was all her own fancy, Marguerite thought, her own imagination taking strange flight. Well, she had no time for fancy now. This was the moment for action.

She had not expected to see Nicolai Ostrovsky again so soon in her life, to have him dropped before her like a ripe prize plum. She had watched him throughout the banquet and during the recital in Henry’s fine new theatre, observing him closely while staying out of his sight.

How very careless he seemed, how caught up in laughter and jokes, the doings of his own companions! How had he ever survived his life of travel and intrigue? She had heard tell of how deftly he moved through the treacherous Courts of Venice, Mantua, Naples, Madrid. Yet he seemed to take no notice of the danger swirling around him.

He could not be so careless and still live, Marguerite knew that well. He and she were two of a kind in many ways, making their way in a cold world with only their wits, their blades, their good looks—their ability to pretend, to be all things to all people. But in his eyes she saw no flicker of awareness, no tense watchfulness like she always felt in herself. And she had watched him very closely all evening.

She finally had to conclude he had indeed taken no notice of her, and that was all to her advantage. Seldom had she found a task so easy. And now it was near to completion. She saw the wing housing the Spanish party just ahead, its silent brick hulk slumbering peacefully.

She slowed her steps, automatically rising on to the balls of her feet as she rounded a marble fountain. The faun poised at its summit stared down at her knowingly, her only witness as she slid the dagger from its sheath beneath her skirt. The hilt was cold and solid in her grasp, a stray beam of moonlight dancing down the polished blade. She was so close now…

Suddenly, a hand shot from behind the fountain, closing like a steel vise on her arm. Startled, Marguerite opened her mouth instinctively to scream, but another hand clamped tight over her lips. She was jerked off her feet in one quick movement, dragged back against a hard chest covered in a soft silk doublet.

Marguerite twisted in that steel trap of an embrace, kicking back with her heels. She managed to work her hand free, and stabbed out with her blade. The sound of tearing fabric echoed loudly in the cold, silent night, but she felt no solid thud of dagger meeting flesh.

“Chert poberi!” her captor cursed roughly. His grasp slid down to her wrist, squeezing until her fingers opened and the knife fell to the pathway.

Of course. She should have known. The Russian. Had she not been sure no one could be as careless as he appeared? Now it seemed she was the careless one.

Her anger at herself, at him, flared up like a white-hot shooting star, and she lashed out madly, kicking and squirming like a wild animal caught in a steel trap.

“Couilles!” she cried out behind his hand.

“Parisian hellcat,” Nicolai growled, his arms tightening around her in a vise. She remembered, in a great fireworks flash, that night in Venice. The coiled, lean strength of his chest and abdomen, the way his long, lazy body, so lithe from years of backflips and somersaults, concealed a core of steel. Her only weapon against such hidden strength was speed and surprise, and she had squandered those with her own carelessness.

She had underestimated him twice now. She could not do so again.

If, that is, she ever had another chance. He could very well slit her throat now, and leave her for the English crows.

The thought was like a cold, nauseating blow to her stomach, and she bent forward in one last struggle to break free. He was too lithe to let her go, though, his body moving with hers.

“We meet again, Emerald Lily,” he said in her ear, his voice full of infuriating amusement. “Or should I say Mademoiselle Dumas?”

“Call me whatever you like,” she said, as his fingers at last loosened over her mouth. “I shall always think of you as cochon. A filthy, barbaric Russian!”

He clicked his tongue chidingly. “How you wound me, mademoiselle. And one always hears of the great charm of the French ladies. How sad to be so disillusioned.”

“I would not waste my charm on you. Muscovite pigs have no appreciation of such delicacies.”

“How you wound me, petite.” He spun her around, backing her up until she felt the solid brick wall at her back, chilly through her velvet. He was outlined by the moonlight, his hair a shimmering curtain, falling in a golden tumble over one shoulder. His face was in shadow so she could not read his expression, but his breath was cool on her cheek, his clean, summery scent surrounding all her senses. He wore no wrap against the cold, and his body in the thin silk was hot where it pressed against her.

She shivered, suddenly frightened beneath her anger.

“I should be the one hurling angry names about,” he said chattily, as if engaged in light conversation in the banquet hall. “After all, mademoiselle, you are the one who tried to kill me. Twice now, if I am not mistaken.”

“You have something that belongs to me.”

“Your pretty dagger, you mean? Ah, but I believe it belongs to me now. I claimed it as a forfeit that memorable night in Venice.”

Marguerite twisted again, overcome by the nearness of him, his heat and strength. She hated this sensation of losing herself, of falling into him, of drowning! “You should have died then.”

“Perhaps I should have, but it seems I have one or two lives yet to go. Fate, mademoiselle, has other plans for me. For us both, it would seem, for here we meet again. What are the odds of that?”

“Fate? Do you believe in it?”

“Of course. Do you not?”

“I believe in skill. In hard work. We all make our own fate, monsieur.”

“Ah, ‘monsieur’ rather than cochon! I must advance in your estimation.”

Marguerite tilted her head back against the hard wall, staring at him in the moonlight. He was certainly still handsome, the sharp, symmetrical angles of his face softened by that mocking half-smile, his pale blue eyes glowing. His hair, his lean acrobat’s body—all perfection. But beauty, as Marguerite well knew, was only a tool, a weapon like any other that a person could learn to wield with skill. She was usually unmoved by that weapon, both in herself and in others. Unmoved by a handsome man’s touch.

Why, then, did his clasp make her tremble so? Make her thoughts tilt drunkenly in her mind? She had to get away from him, to regroup.

She pressed back tight against the wall, but he followed, his hair trailing like silk over her throat, her bare décolletage above the velvet bodice. “I have esteem for any worthy enemy.”

“Am I a worthy enemy?”

“You have defeated me twice now, which no one else has ever done. You are obviously strong and clever, monsieur. Yet you will not defeat me three times.”

His smile widened. “I see I shall have to watch my back while I am in England.” “At every moment.”

“I shall consider myself fairly warned, mademoiselle.”

They stood in silence for a long moment, studying each other warily. Marguerite glanced away first, her gaze shifting over his shoulder to the stone faun, who seemed to laugh at her predicament.

“What are you doing here?” she asked tightly. “Do you work for the Spanish now? Was your task in Venice complete?”

He laughed, a low, rough sound that seemed to echo through her very core. “Mademoiselle, you must know I work for no one but myself. As do you. And as for what I am doing here at Greenwich—well, I must keep some secrets, yes?”

Secrets. That was all life was. Yet Marguerite had spent her own life keeping her own secrets, and discovering those of other people. Even ones they thought so well hidden. She would find his, too.

He seemed to have read her very thoughts, for he leaned closer, so close his breath stirred the fine, loose curls at her temple, and his lips softly brushed her cheek. “Some things, petite, are buried so deeply even you cannot dig them out again.”

“Secrets are my speciality,” she whispered back. “I have not met a man yet who could withhold them from me. One way or another, I always fulfil my task.”

“Ah, but I am not as other men, Mademoiselle Dumas.” He pressed one light, fleeting kiss to her jaw, so swift she was not even sure it happened. “I shall look forward with great anticipation to our next battle. Do svidaniya.”

Then he let her go, his hands and body sliding away from her as one long caress. He melted away, vanishing into the night as if he had never been there at all. Except for the spot of fire that marked his kiss.

Marguerite spun around, but she could find no glimpse of him, no trace of his bright hair or red silk doublet. She was completely alone in the cold garden.

“Abruti,” she muttered. Her whole body felt boneless, exhausted. She longed to fall to the walkway in a heap, to sob out her frustration, to beat her fists against the jagged gravel until they bled!

But there was no time to give into such childish, useless tantrums. Womanish tears would never gain her the revenge she sought, would never achieve her goals for her. So, she scooped up her dagger where it had fallen and hurried back toward the palace, running up the stairs to her quiet little room.

Soon, very soon, a new day would dawn. A new chance to at last best the Russian and get back her emerald dagger.

This time, she would not fail.

Nicolai closed the door to his small chamber, sliding a heavy clothes chest in front of it. He was wary enough to take the Emerald Lily at her word. She would be coming sooner or later for her dagger. At least this way she would have to make a great deal of noise forcing the door open. Unless she could somehow transform herself into a column of mist and come down the chimney, which would not surprise him in the least.

She was not like any woman he had ever met, this French fairy-sprite. She looked so very delicate, so angelic, and yet she was a veritable hellcat. A powerful, shrieking vodyanoi, a sea witch, just like the terrifying tales his nurse told him when he was child.

Perhaps her claws only came out in the moonlight, though, for at the banquet she was all smiles and light charm, even with the dour young priest who sat beside her. None of the men in the vast hall could turn his eyes from her, and that included him, though he carefully did not let her see that. He pretended not to notice her at all, to let her think herself safe, yet in truth he had seen her as soon as she walked in at the end of the French procession.

How could he help it? It was as if she was surrounded by a silvery pool of light. His Emerald Lily. The woman who incited his lusts and then tried to murder him.

He knew she would come for him. She was rumoured to be ruthless to the enemies of France. Such as what had happened to a certain Monsieur Etampes, who dared attempt to be a double agent for Spain! A grotesque end indeed. And Nicolai had slighted her by daring to live.