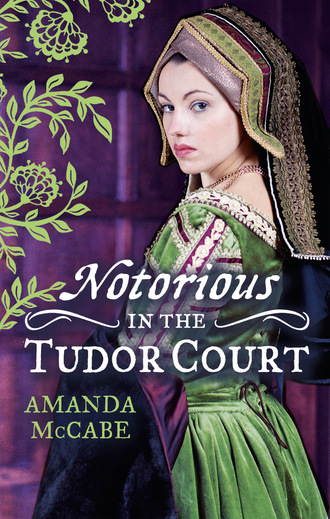

Полная версия

NOTORIOUS in the Tudor Court

“A good wife would settle you, Nicolai, make a home for you, as Julietta has for my son,” she said. “Do you not desire a family?”

Fortunately, he was saved from her matchmaking by a round of seasickness that overcame Dona Elena and many of her ladies. He did not have time to fend her off and plan for their troubled mission in England!

Ostensibly, he was meant to be a sort of Master of the Revels to the Spanish party, devising entertainments to impress the English Court and the French, to show off Spanish wealth, piety and strength in the face of all their challenges. His years as a travelling player and acrobat would stand him in good stead in such a task, and in his less obvious assignments as well. Not only was he to protect Dona Elena and her new husband, he was to keep an eye out for the interests of the Tsar of Russia. Tsar Vasily III had seen much success in his new trading schemes with the East, and now thought to expand westward as well.

Tricky, indeed, to balance France, Spain, England, Venice, Russia on an acrobat’s tightrope. And a far cry from the pleasurable winter he had once envisioned! But it was blood-stirring, as well. Masqueing was his life’s work, and there was none better at it than he was. This English meeting was a challenge greater than any he had faced in a long time, and he was ready for it. And, if he had his way, it would be his last dangerous mission, as well.

Nicolai reached for the sheath at his waist and drew out a dagger, balancing it on his gloved palm. The emerald in the hilt gleamed in the pale light, glinting with a silent threat—a promise—that had yet to be answered.

He tossed it lightly into the air, catching it so he could see the tiny lily etched into the finely honed steel. He carried the dagger everywhere, a reminder that once he had met the notorious Emerald Lily, the shadowy French assassin feared throughout Europe. Met her—and bested her, though more by luck than any great skill on his part.

He never spoke of that strange night in a Venetian brothel to anyone, not even Marc and Julietta. For one thing, except for this dagger, he could not be sure it was not a dream. For another, he could never convey the power those eyes, as green as this emerald, held over him, from the first moment he glimpsed them through the smoke and haze of that whorehouse’s common room.

She was beautiful, truly, like an angel or a fairy with that silvery hair, yet her allure that night was far more than mere loveliness. A thousand women possessed that. It was those eyes. So hard, so cold, yet with a spark underneath that could not be extinguished.

It was foolish of him to leave her alive, to show a mercy that was so unlike him, and that she would never have shown him. The Emerald Lily was rumoured to be ruthless, and she would not take well to being made a fool of. She would come after him again one day, probably when he least expected it.

Perhaps that was what made him leave her there, trussed up on the rumpled bed. The knowledge—or was it hope?—that they would one day meet again. She would want her dagger back, after all.

The trouble was, another meeting would surely leave one or both of them mouldering in the grave.

Nicolai tossed the blade in the air again, catching it with a light twirl of his fingertips. Until that fateful day, he had more to worry about than beautiful, green-eyed killers.

And his chief worry was coming toward him right now.

Dona Elena appeared on deck, followed by two of her ladies who had recovered from their mal de mer. She certainly seemed the pious Spanish matron, her coffee-brown hair, only lightly streaked with silver, smoothed back beneath a pearl-edged, veiled cap, garnet-crusted cross clasped around her throat. A black cloak covered her dark red gown, shielding her from the salty wind, and her gloved hands held a gilt-edged prayer book. But her soft brown eyes were full of determination.

Her son, Marc, surely got that from her. The Velazquez family always got their own way.

“Ah, Nicolai, there you are!” she said, joining him at the rail. “The captain says we will without doubt make land today.”

Nicolai gestured toward the horizon, where towering, stark white cliffs were just peeking through the mist. “At any moment, Dona Elena.”

“Thanks be to God.” She quickly crossed herself. “This voyage has not been enjoyable.”

“It is seldom a good idea to set out in the middle of winter.”

Elena sighed. “Especially for someone as accustomed to the comforts of land as me! I know Marc would have preferred I stay at home in Madrid and wait for Carlos to return, yet he does not understand. He and his wife are always together now, but it has been a long time since I enjoyed the pleasures of marriage.” She frowned, and Nicolai knew all too well what was coming. “The comforts of a home, Nicolai, are inestimable. If you only knew the great benefits…”

By the time he had fended her off, and sent her and her ladies below decks to finish their packing, the ship had drawn closer to the rocky shore, those cliffs looming like a stark white welcome.

The rough sea voyage was ending at last, yet Nicolai feared his travails were only just beginning.

Chapter Three

Marguerite sat bundled in her cloak at the back of the barge as they made their way along the Thames, her sable-edged hood eased back so she could observe the scenery as it glided past. The English were so proud of their little river, lined with the estates of their nobles! Their escorts, a brace of Henry’s courtiers sent to guide them to Greenwich, gestured toward stone towers and brick halls, declaring them the abodes of the Carews, the Howards, the Poles.

Marguerite sniffed. If they could only see the vast, fairy-tale spires of the châteaux along the Loire! They would not be so quick with their boasts then, these swaggering English boys.

She had to admit, though, they were handsome enough. Rumour said that Henry enjoyed being surrounded by young people, full of energy and fun and high spirits, and their escorts seemed to confirm that. Tall, strong men, bright-eyed, lavishly dressed—if not as stylish as Frenchmen, of course. Quick with a jest as well as a boast, and with a keen eye for a pretty face. Each of them had already bowed before her, and she was one of the least of the French party.

Still pretending to study the river, she actually watched them from the corner of her eye, those exuberant young men. If they were full of guile and trickery, as all men were, they hid it well. There was no hint of suspicion on their handsome faces, no flicker of deception in their laughing voices.

Her task here was either going to be easier than she expected, or far harder.

“Have you even been to England before, Mademoiselle Dumas?”

She turned to see that one of the English courtiers, the raven-haired Roger Tilney, had sat down beside her on the narrow bench.

She smiled at him. “Never. I have been to Italy, but not your England. It is fascinating.”

“Wait until we arrive at Greenwich, mademoiselle. The king has prepared a great surprise there, and there will be many entertainments every day from dawn until midnight.”

Marguerite laughed. “Many entertainments? And here I thought you men had most important business to see to!”

“One cannot work all the time, especially with such welcome distractions in sight.”

He leaned closer, and she found Englishmen did not smell like the French, either. His cologne was spicy rather than flowery, overlaying the crisp cold of the day, the scent of wool and leather.

Hmm. Surely this Master Tilney was correct—one could not work all the time.

Yet that was exactly what she had to do. Work all the time. For it was in the instant she let her guard down that all went awry. The Russian had taught her that.

“I do love to dance,” she said. “Will there be time for such frivolous pastimes?”

Tilney laughed, and she felt the swift, warm press of his hand on her arm through her thick cloak. “Dancing is one of King Henry’s greatest delights.”

“I am glad to hear it. A Court that does not dance or make merry music could be called…”

“Spanish, mayhap?”

They chuckled together at the naughty little dig. As Marguerite pressed her hand to her lips to hide her giggles, she noticed Father Pierre watching her, a frown on his pale, thin face.

She turned resolutely away from him, determined that his stares would not distract her today.

“I do hear that the Spanish care little for such worldly pursuits,” she murmured. “But is your own queen not Spanish? What does she think of dancing?”

Tilney shrugged. “Queen Katherine is usually of good cheer. She is most indulgent, and famous for her serene smile and even temper. She may no longer dance herself, but she is a gracious hostess.” “Usually?”

He opened his mouth to reply, then seemed to think better of it. Instead he smiled, and gestured to the bank of the river. “See there, mademoiselle. Your first glimpse of the palace of Greenwich.”

Marguerite leaned to the side, watching closely as the barge slowed on its approach. Greenwich was not pale and graceful, as François’s plans for Fontainebleau were. It obviously did not intend to convey a deceptive delicacy. It was long and low, and pretended to nothing but what it was—a strong palace, a home yet also the receptacle of power.

The pitched roof was as grey as the sky above, blending with the wispy smoke that curled from its many chimneys, but the walls were faced in red brick in the old Burgundian style.

There was no moat or fortifications; that would have been too old-fashioned even for the English. Instead, narrow windows, glinting like a thousand watchful eyes, stared out over the river.

“It is very pretty,” she said. “A fit setting for revels, I would say.”

“It is built around three courtyards,” Tilney said. “Perfect for games of bowls. And there are tennis courts and tiltyards.”

Marguerite laughed. “It does sound a merry place. Dancing, bowls, tennis…”

“Ah, mademoiselle, I fear you will think us nothing but frivolous! Look you there, the Church of the Observant Friars of St Francis. The queen is their patron, and they are always there to remind us of a higher purpose.”

“And to immediately take your confession when needed?”

“That, too.” Tilney was summoned to join the English courtiers as the barge docked, and Marguerite went to see if Claudine, the Comtesse de Calonne, required her assistance. The young comtesse was enceinte, and the voyage was not a comfortable one for her. She bore it all well enough, her face so pale that her golden freckles stood out in stark relief, but she spent most of her time with eyes tightly shut, listening to one of her ladies read poetry aloud while another massaged her temples with lavender oil. She did not often need—or want—Marguerite’s assistance.

The rumours of her handsome husband’s many infidelities could not help her temper, either. The comte and comtesse were cousins, married very young, but it was said Claudine cared more for her husband than he did for her.

“We have arrived, madame la Comtesse,” Marguerite said, kneeling beside Claudine to help her gather her gloves and smooth her cloak and headdress. “Soon you will be tucked up in your own feather bed, with a warm fire and a cup of spiced wine.”

Claudine smiled tightly. “Or more likely pressed into a cold room with ten other people and only ale to drink! These English—pah. They do not understand true hospitality.”

“Then we must teach them, madame!” Marguerite nodded to one of Claudine’s maids, and between them they helped her to her feet so she could join her husband in disembarking. “We will set a fine French example.”

“At least they sent a cardinal to greet us,” Claudine said, gesturing to the man in scarlet who awaited them, surrounded by so many attendants in black he seemed enmeshed in a flock of crows. “Not some mere clerk.”

“I am sure King Henry has a better sense of protocol than all that,” Marguerite replied, examining the man. It had to be Wolsey himself—the dangerous, all-powerful Wolsey—for he had the wide girth and long, bumpy nose of his portraits.

She had heard tell that the great Cardinal, Archbishop of York, the one man Henry relied on above all others, wore a hair shirt beneath his opulent scarlet velvets and satins. And Marguerite could well believe it, to judge by his pinched, grey face. He did not look like a well man. Still, she would not like to cross swords with him. It was fortunate he promoted the French treaty so assiduously.

Marguerite fell into step behind Claudine as they all left the barge and the play commenced at last.

Claudine’s fears proved to be unfounded, for she was given an apartment to herself, albeit a rather small one almost beneath the eaves of the palace. Marguerite had an even tinier room tucked behind, a closet with scarcely space for a bed and clothes chest, and one tiny window set high in the wall. But the insignificant space was perfect for her needs—private, quiet, and, as the page told her, near a hidden staircase that led to the jakes and then out to the gardens.

Ideal for secret errands.

Left to her own devices while Claudine rested before the evening’s festivities, Marguerite set about unpacking her travelling cases. All the velvet gowns and silk sleeves, the quilted satin petticoats and jewelled headdresses, were shaken, smoothed and tucked with lavender into the chest. The high-heeled brocade shoes and embroidered stockings, her small jewel case and fitted box of toilette items, were arrayed on top.

Once the case was emptied of its fine, feminine cargo, Marguerite lifted out the false bottom. There, carefully swathed in cotton batting, were her daggers and her sword.

The blades were made to her own specifications in the king’s own forge, smaller and lighter to fit her size and strength, perfectly balanced, delicate as a dancer, strong as marble.

Holding her sword outstretched, she took up a fighting stance and thrust once, twice at the air. The steel sang in the cold breeze, a quick, fatal whine, then perfect silence. It was truly a thing of beauty.

Smiling, she tucked it safely away, where it could rest until needed. She took up one of the daggers, a thin blade that appeared almost as dainty, and useless, as a lady’s eating knife. But it was designed to slip quickly, neatly, between a man’s ribs, leaving only a fatal drop of blood behind.

The hilt was set with tiny rubies, winking in the hazy light like serpent’s eyes. For a moment, she remembered her old blade, her favourite, with its rare emerald.

She remembered, too, how she had lost it. But one day she would get it back.

Marguerite lifted the hem of her skirt, tucking the blade into a sheath attached to her garter. She couldn’t think about him now. He had no place here. She had her errand laid out before her, and it would begin with tonight’s formal banquet to welcome their delegation. She needed to bathe and change her gown, to don her disguise of velvet and pearls.

Why, then, did it seem like the Russian followed her everywhere she went, and had for more than the last year? Those icy blue eyes…

Marguerite slammed the lid of her case and pushed it beneath the window, as if she could break his memory in two. The tiny pane of precious glass was so high she had to climb atop the case to see out. Her room looked down on one of the three courtyards Tilney had told her of, a carefully laid-out garden that slumbered in the winter chill. The square and diamond-shaped flowerbeds were brown and brittle, the trees bare, the fountains still. Yet she could clearly see that come summer it would be spectacular, a riot of roses, lilies, violets, gillyflowers, scented herbs, green vines twisting over the low railings and trellises.

The gardens were hardly dead now, for people strolled along the white gravel pathways, their Court raiment as bright as any flower could hope to be. Were they English, French, Spanish? She could not tell from her high perch. But she would know all soon enough.

Chapter Four

“And you see there, Master Ostrovsky, the king’s newly built banquet house. And, over there, at the other end of the tiltyard, the theatre,” Sir Henry Guildford, the king’s Master of the Revels, said, waving toward a long, low wooden building as they strolled through the gardens. Even at this late moment, as the sun set on the first day of this vital meeting, workmen scurried about, hammering, sawing, putting the last details in place on these new structures.

“That space shall be for the planned pageants and masquerades,” Guildford said, leading Nicolai toward the theatre. They ducked around a crowd of servants building two towering silk trees, a Tudor hawthorn and a Valois mulberry. “The king is also very fond of spontaneous disguisings, but one never knows when those will occur, no matter how organised my office strives to be.”

The tightening of Guildford’s mouth in his plump face was the only sign of the vexation such “spontaneous” displays engendered. The Master of the Revels was meant to oversee all the Court’s entertainments, even to keeping account of all the costumes and properties, the casting of various roles. That could not be easy when the one person most meant to be impressed by these careful displays kept subverting them!

Nicolai had a hard enough time herding his own small troupe on their travels. He did not envy Sir Henry his task of shepherding an entire Court. “It must be a fine thing to have your own space for this great task, Sir Henry,” Nicolai said, nodding toward the new theatre.

“‘Tis not only my space, Master Ostrovsky. We must share it with the Master of the King’s Minstrels and his musicians,” Guildford answered. “But there is room for us to store our properties, which is a blessing. Usually they must be fetched from a great distance.”

Nicolai’s props were often stored in a painted wagon, with more dangerous items hidden among the masks and bells. Items for more—discreet tasks. But he merely nodded understandingly.

“We are very glad to welcome you here, Master Ostrovsky,” Guildford went on. His smooth tone gave no hint of curiosity about what Nicolai, a player and a Russian to boot, might be doing among the Spanish party. “Assistance with our revels is always greatly to be desired, and Señor Mendoza tells us you have much experience with Italian pageants. All things Italian are very fashionable, you know.”

“It is true I am recently come from Venice,” Nicolai answered.

“Ah, yes, the Venetians. They do enjoy their masquerades and fêtes, do they not? Excellent, excellent! I have so very many tasks, and most of my idiotish assistants can do naught unless I watch them at every moment.”

“I am happy to assist in any way I can, Sir Henry.” In Nicolai’s experience, it was often the actors at Court—both the professionals from the Office of the Revels and the courtiers who so often took on roles—who knew most of the secrets. The hidden plans and desires. If he could do what he did best, insinuate himself into a play, his task would be that much easier.

“The king has ordered a different entertainment for almost every evening. I will be happy of your assistance in directing some of our players.” Sir Henry shook his head, muttering, “The ladies all want to take part, but they do not want to work, you see. Merely gossip and giggle together without learning their lines and postures.”

Nicolai laughed. “I am told I work well with the ladies, Sir Henry.”

“I would wager you do. They always seek to impress a handsome face. Well, here we are at the theatre, then. Just long enough for a quick glance round, I think, before the sun quite vanishes.”

Sir Henry opened the tall double doors of the new theatre, the rich wood carved with vines and flowers, surmounted by the king’s Tudor roses and portcullises, the queen’s pomegranate of Granada and arrow-sheaf of Aragon.

How long, Nicolai wondered, would those badges remain, if the rumours were true? The tales of a certain Mistress Boleyn and the king’s anguish over his lack of a son. And what vast trouble would their removal cause?

Today, though, the pomegranates were firmly in place, boasting of a long, solid marriage, a firm dynasty. Sir Henry led Nicolai into the interior of the theatre, so new it still smelled of paint and sawdust. It was beautiful, unlike any place Nicolai had ever performed in before. Long, soaring, lit with a profusion of flickering torches, the theatre gave the impression of a celestial realm. The ceiling was painted the pale blue of a summer sky, while below was hung a transparent cloth painted in gold with stars, moons and the signs of the zodiac.

Seats rose in tiers along the walls, while at the far end a large proscenium arch marked the performance space. Workmen were still putting in place terracotta busts and statues.

“‘Tis a most glorious space, Sir Henry,” Nicolai said truthfully. “And yet you say it is just temporary?”

“Oh, I am sure we will find a use for it once the French depart,” Sir Henry said. “But it is all wood and gilt, meant to deceive.”

He led Nicolai behind the arch, where several trunks were stacked. Scrolls, lengths of bright satin, cushions and spangles spilled forth in a confusing jumble. As Sir Henry dug through the glittering array, a chorus of angelic voices rose up somewhere in the shadows, a tangle of silvery sound that grew and expanded, soaring up to the ceiling-sky. Nicolai turned his head to listen, enchanted.

“The chorus of the Chapel Royal,” Sir Henry said. “They are to give a recital after tonight’s banquet. Fortunately, they are not my responsibility. Ah, here we are!”

He drew out a scroll, untidily bound with a scrap of ribbon, and handed it to Nicolai. “This is to be the pageant to follow the king’s great tournament a few weeks hence. With your permission, Master Ostrovsky, I put you in charge of it.”

Nicolai quickly read over the programme. “The Castle Vert?”

“The Green Castle, yes. An old piece, perhaps, but always a Court favourite. As you see, there are roles for all of sixteen ladies.”

Sixteen? “Are the parts already cast?”

“Not at present. Lady Fitzwalter and Lady Elizabeth Howard must have a turn, of course. And Mistress Anne Boleyn, who at least knows how to sing and dance already. Oh, and they say there is a lady among the French who is uncommonly lovely. A veritable angel, according to Master Tilney. Perhaps it would be a diplomatic gesture to cast her as Beauty. But, Master Ostrovsky, I leave it all up to you. I must work on The Fortress Dangerous, which fortunately only calls for six ladies.”

Sir Henry clapped Nicolai affably on the arm, and turned to hurry off on some new task. “Good fortune, Master Ostrovsky, and my deepest thanks! I will send some of my staff to assist you on the morrow.”

Nicolai grinned ruefully, slapping the scroll against his palm. Fifteen English Court ladies, and one French angel, all vying for their selected parts. All of them with the force of family and faction behind them.

Oh, Marc, Nicolai thought. I hope you appreciate what I do for the sake of friendship!

The French delegation was to gather in Queen Katherine’s presence chamber before progressing to the great new banquet hall. Once Marguerite was bathed and dressed, in a gown of emerald green velvet over an embroidered petticoat of gold satin, her wide oversleeves turned back to reveal more gold and a sable trim, she joined the others in Claudine’s apartment to wait for Bishop Grammont and his officers, including Claudine’s husband, the Comte de Calonne.

A rest seemed to have done Claudine some good, Marguerite observed. She was not as pale, and even looked a bit rosy in her dark crimson silk gown, her stays loosely laced over her swelling belly. That was very good. If she was confined to her chamber, then Marguerite, her ostensible attendant, would be hard pressed to find excuses to go about in Court.