Полная версия

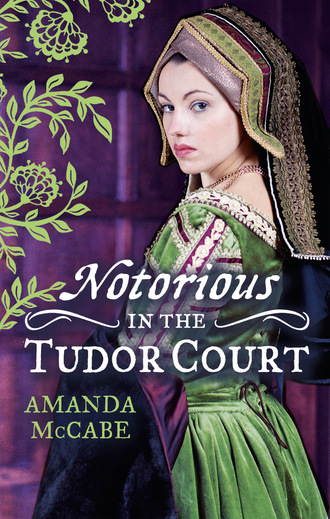

NOTORIOUS in the Tudor Court

She remembered too well the taste of his mouth in Venice, the feeling of his lips on her body, those graceful fingers on her stomach, her breasts. He was surely as skillful in the arts of lovemaking as he was on that rope.

Yes, she lost herself for a moment, drowned in the force of that cursed Russian’s allure and charisma. Only Sir Henry’s arrival saved her, and she had to flee when she heard she was actually to be working with Nicolai!

“Idiot,” she muttered. She could not succumb to weakness now. There were yet long days ahead here in England, and she needed her wits and skills to see her through. She would not give in to the allure of a lithe body and golden hair.

Remember, he stole your dagger, she told herself sternly. She had to get it back, and find out what his business was among the Spanish.

She closed her eyes, envisioning a sheet of pure, white ice encasing her whole body, her mind and heart, erasing the heat and light of Nicolai Ostrovsky. When she opened them again, she felt calmer, more rational.

She lowered her book to her lap, hands steady. Passion, agitation, achieved nothing. Her feelings for Nicolai were a mere physical manifestation, her weak, womanly body clamouring for pleasure. Focusing on her work would soon overcome such foolishness.

Marguerite heard a burst of laughter, a flurry of chatter in Spanish, and she turned to see a group of ladies strolling toward her. At their head was the woman Nicolai sat next to at the banquet, the one with the sweet smile. That smile was in evidence now as she drew near Marguerite’s bench.

“Ah, señorita, are you alone this afternoon?” she asked. As she stopped before Marguerite, her dark red velvet skirts swaying in a cloud of violet scent, Marguerite saw she was older than she first appeared. Tiny lines fanned out from her brown eyes and her lips, and grey threaded her brown hair at the temples. She was obviously quite wealthy, too, with a heavy garnet-and-pearl cross around her neck, hanging low over her fur-trimmed surcoat, and pearl drops in her ears. An important member of the Spanish party, then, Marguerite decided. But her eyes were kind.

Marguerite stood up to make a curtsy. “I am reading, señora…”

“This is the Duchess of Bernaldez,” one of her attendants said sternly.

The lady waved these words away. “Dona Elena when we are outdoors, if you please, Esperanza.” She whispered to Marguerite, “I have spent many years at a quiet convent, you see, and have yet to become accustomed to the strict etiquette my husband seems sadly to enjoy so much.”

Marguerite laughed in surprise. “I, too, prefer informality. I am Marguerite Dumas, Dona Elena.”

“I know. You are quite famous, Señorita Dumas.”

“Famous?” Oh, no. That would surely make things so much more difficult! It was hard enough to engage in subterfuge in a crowded Court without being well known.

“Of course. The men can talk of nothing but your rare beauty. I see now why that is so.”

“You are very kind.”

“I just speak as I find, and I must say I enjoy having beauty around me as much as anyone. It brightens these grey English days. Would you care to walk with us? We were going to take a turn by the river.”

Ah, an opportunity! They so rarely just fell into her lap like that. Hoping to compensate for her silly behaviour with Nicolai, Marguerite nodded and said, “I would be honoured, Dona Elena.”

She fell into step next to the duchess as they strolled around the palace to the long walkway that ran beside the Thames. The river was placid today, grey and flat as a length of sombre silk, broken only by a few boats and barges floating past on their way to London and the sea. Dona Elena’s attendants gradually went back to their conversations, their whispers like those waves that broke and ebbed along the banks.

“You have not long been married, then, Dona Elena?” Marguerite asked.

“A few months only. My first husband, a sea captain, died many years ago, señorita. I loved him a great deal, and when he was gone I sought the refuge of a convent. I thought to stay there for the rest of my life.”

“Until the duke swept you off your feet?” Marguerite teased.

Dona Elena laughed. “You certainly have it aright! His sister, you see, is abbess of the convent, and we met when he came to visit her. We spent a great many hours walking in the garden together, and before he left he asked me to marry him.”

“Such a romantic story!”

Dona Elena gave her a wink. “And an unlikely one, you are thinking. An old lady like myself—why would an exalted duke choose such a wife?”

“Not at all, Dona Elena. You can hardly be so ‘old’ and still be so beautiful.”

“You do possess the art of flattery, Señorita Dumas. I had heard that of the French.”

“Like you, I must speak as I find.”

“Are you married yourself?”

Marguerite shook her head. “I fear not.”

“I was first married when I was fifteen. My new husband was also wed when he was quite young, and his wife gave him many children before she died. We did our duty in our youth, you see; we have our families. Now we are blessed to find companionship and affection in our old age.”

“It sounds a marvellous thing indeed, Dona Elena. I can only pray to find such contentment myself one day.”

“You must surely have received many offers!” Dona Elena examined her closely, until Marguerite felt her blush returning. “I wonder you are yet unwed.”

“My duties at Court keep me very busy. And, too, I am an orphan, with no one to see to such matters.”

“Oh, pobrecito! How very, very sad.” Dona Elena took Marguerite’s hand in her plump, be-ringed fingers, patting it consolingly. “Have you been alone in the world very long?”

“My mother died when I was born, and my father died above seven years ago.”

“And you were their only child?”

“I fear so.”

Dona Elena sighed. “I have but one child myself, my son Marc. He has been the greatest blessing of my life, but I would have wished to give him brothers and sisters.” She drew a gold locket on a chain from inside her surcoat, opening the engraved oval to show Marguerite the miniature portrait inside.

Marguerite peered down at the painted image of a dark-haired young man. “He is certainly very handsome.”

“That he is. And he is soon to make me a grandmother!”

“How very gratifying. You must wish to hurry back to Spain to see the new baby.”

Dona Elena pursed her lips as she snapped the locket shut. “Alas, he makes his home near Venice now. But I hope to see him again soon after we leave England.”

Whenever that would be. Marguerite feared they would all be at Greenwich, strolling round and round the gardens for weeks to come, with nothing at all resolved. And she could not even devise how to discover what this lady knew of Nicolai.

“You must wish for children of your own one day, Señorita Dumas,” Dona Elena said.

For one flashing instant, Marguerite remembered the kicks of the horse’s hooves, the burning, searing pain in her belly. Her twelve-year-old body, barely budding into womanhood, bleeding on to the ground. “If God wills, Dona Elena,” she said, knowing full well His will for her had already been revealed. He turned from her long ago.

“If you were one of my ladies, I would have you settled with a fine husband in a trice,” Dona Elena said confidently. “Even from the convent, I arranged seven happy marriages among the children of my friends! I am known for my eye for a good match.”

Marguerite laughed. “That must be a useful gift indeed, Dona Elena.”

“It gives me great satisfaction. Some people, though, do not trust my skills. They resist what is best for them.”

“Do they? I vow I am convinced, Dona Elena! I would be happy to put my fate in your hands, if I was fortunate enough to be one of your ladies.”

Dona Elena shook her head ruefully. “If only you could help me convince poor Nicolai.”

“Nicolai?” Marguerite asked innocently, a bubble of excitement rising up in her at the mere mention of his name. She was a fool in truth.

“Nicolai Ostrovsky, who is a friend of my son. He leads such a disorganised life, señorita! Travelling up and down, no home of his own, though his fortune could surely afford one. Such a lovely gentleman.”

“Is he the handsome one, with the golden hair?” Marguerite whispered.

“Ah, you see, Señorita Dumas, even you have taken notice of him! All the ladies do. I have told him many times that any of my young attendants would be most happy to marry him, but he refuses.”

Marguerite glanced back over her shoulder at Dona Elena’s chattering ladies. They were pretty enough, she supposed, with their smooth, youthful complexions and shining dark hair. Surely too young and pious and—and Spanish for Nicolai! How could any of them possibly understand a man like him, when not even Marguerite herself could?

“Does he give a reason for his refusal?” she asked casually.

“Only that his life has no room for a wife. But I say he grows no younger! If his life has no room for a family, he must change his life. Make a home before it is too late.”

A home. Marguerite feared she did not even know what the word meant, as wondrous as it sounded. “He must be a great friend to your son, Dona Elena, for you to take such concern.”

“He is indeed! He saved Marc’s life.”

Very interesting. “How so?”

“I do not know the particulars. It happened in Venice. Or was it Vienna? No matter. He saved my son, and I shall always be grateful to him. And now he comes all this way to watch over me! Such a good man, señorita. If only he would let me repay him by finding him a fine wife.”

They walked on, the conversation turning to lighter matters of fashion, but Marguerite’s thoughts whirled. Could it really be that Nicolai was not here at Greenwich on matters of state and politics, but merely—friendship?

It scarcely seemed possible. Marguerite had never heard of such a thing. There must be something else, something Nicolai hid from the sweet Dona Elena, that brought him to this meeting. He had to be in the pay of someone else. But what was it he really sought?

Marguerite was more determined than ever to find out.

Chapter Eight

“What will you wear tonight, mistress?” asked Marguerite’s borrowed English maid, sorting through the clothes chest.

“Hmm?” Marguerite asked, distracted. She was sitting before her small looking glass, restlessly moving combs and jars about though she was meant to be dressing her hair. She would never be ready for the banquet in time if she carried on like this! Then she would have to go down in her chemise and stays. “What do you think?”

The maid examined the jumble of garments, at last holding up a skirt and bodice of silver-and-white satin. “This one, mistress! And the gold tissue sleeves.”

It was one of Marguerite’s best outfits, with the trim worked in a flower pattern of tiny crystals and silver-gilt embroidery, and she had meant to save it for the end of their English stay. But she remembered Dona Elena’s pretty attendants, her vow to see Nicolai married to one of them. It aroused in Marguerite a fierce, irrational yearning to outpretty them all, to capture Nicolai’s gaze and hold it only to herself. To never surrender it to some Spanish ninny, who might indeed make a fine, sweet wife, but who could never keep his interest for long.

“Abruti!” she cursed, throwing down a comb so hard one of the delicate teeth snapped. What was wrong with her tonight? She didn’t want Nicolai’s attention. Indeed, those unearthly blue eyes watching her just made her task that much harder. And it was nothing to her if he married fifty featherbrained Spanish girls. A hundred, a thousand!

Marguerite pressed her hands to her temples, feeling the throbbing veins just under her skin. She had sometimes heard of François’s spies going mad under the unceasing pressure of their work, turning into raving lunatics who had to be locked away because they no longer knew friend from foe. Was that what was happening to her?

“Non,” she whispered.

“Mistress? Is aught amiss?” the maid asked, her voice full of concern. Perhaps she did not often see ladies throw small tantrums, as the placid, polite English queen kept everyone under such control.

“Nay, I think I am just tired,” Marguerite answered steadily. “The white will do very well. You have a good eye.”

As the maid laid out the garments, Marguerite reached for her bottle of perfume. It was a special scent, blended for her by the royal perfumer. Her father used to tell her how her mother wore the fragrance of springtime lilies all the time, so Marguerite wore it, too. Its fresh sweetness seemed to revive her now, quiet the rush of her blood.

She was tired, that was all. The long journey, and now this unceasing round of activity. She could scarcely draw breath, let alone think. And Nicolai was just an unexpected complication.

She had to confess she did not understand him, could not decipher him at all. She, who prided herself on her knowledge of people, her ability to discover what motivated them, what they craved, and then using that for her own ends. She had no idea of what Nicolai desired, what brought him here to Greenwich. For all his lightness, his seeming good humour, he had depths she could not read.

Unless he was just here for the Spanish ladies…

The maid held up the white satin skirt, and Marguerite left the looking glass and the mess she had made of her toiletries to let her fasten it over the petticoats, the quilted silver underskirt. Marguerite stood still as the maid adjusted the bodice, the stiff silver stomacher, and tied on the delicate gold sleeves.

Every person had weaknesses, desires. Every person had a price. Nicolai Ostrovsky’s was just harder to find—and surely far more expensive—than most. He had to be up to something—no one would come all this way for the sake of mere friendship. To leap into the fray of Henry, François and Emperor Charles just because a friend asked? Absurd!

Non, he had some agenda, and the Spanish were surely part of it. She just had to be patient and steady, and she would find what his motives were. What price he asked.

To do that, she would have to be very careful. No more temper tantrums. And no more touching his hair! It was clear she could not trust herself in that direction.

She fastened her silver brocade shoes, and let the maid settle the nimbus-shaped headdress over her smooth hair. It was made of stiffened silver satin, embroidered with crystals and pearls that sparkled in the candlelight. The effect was of an angel’s halo, shimmering atop her pale hair.

It was a good fashion choice the maid had made, Marguerite thought, examining herself in the looking glass. Who would suspect an innocent, shining angel of any subterfuge?

Except perhaps Nicolai himself. For had she not compared him to an angel? And he was full of prevarication, of feints and dodges.

Marguerite opened her jewel case and took out a piece she rarely wore but always treasured, a large, square-cut diamond on a thin silver chain. Like the essence of the perfume, it had been her mother’s. Tonight it would give her courage.

When the doors opened on the banquet hall, a gasp went up. Marguerite stood on tiptoe, peering around Claudine’s shoulder to see that the arrangement of the tables was changed. Rather than two long, straight tables, French and Spanish, on either side of an aisle, they were arranged as a large horseshoe, facing the king’s dais.

“My beloved guests!” King Henry boomed, striding toward them like a purple velvet-clad bull, all hearty enthusiasm and good fun. He held Princess Mary by the hand, clad in a matching purple gown. Her large eyes were wary in her pale face.

“Welcome to our feast,” Henry went on. “It is much deserved after all our hard work this day. As we are united in the great cause of peace, so must we be united at the banquet table. My servants will show you each to your seats. We can no longer be divided!”

A murmur of speculation rose up, mutters of excitement and protest. “How can one know one’s proper place, in such an arrangement?” Claudine said, gesturing angrily toward the rounded table.

“Just play along with the English king’s whims, chère,” her husband answered through gritted teeth. “It will be over soon enough.”

Marguerite watched with interest as they were each led away to their assigned seats, men and women, French, Spanish, and English alternating. This could serve her purposes very well indeed! An easy way to chat with the enemy, much like her stroll with Dona Elena. Simple, informal, completely unsuspicious.

Plus, it would get her away from Father Pierre, who appeared to have assigned himself as her official escort, or perhaps guard, while they were at Greenwich. His silent presence at her side, the rustle of his black robes, his strange watchfulness, was becoming an irritant.

She waved to him as he was led away, protesting, to a place at the far end of the horseshoe. A page took Marguerite to a seat at the middle curve, where she was between Roger Tilney and Dona Elena’s husband, the Duke of Bernaldez. Dona Elena, across from them, greeted her happily, telling her husband of their afternoon walk by the river.

“And she listened to me prattling on about Marc, and about how you and I met, mi corazon, with nary a complaint!” Dona Elena said. “Such great patience.”

“Not at all, Dona Elena,” Marguerite answered. “I enjoyed our meeting very much. It can get lonely, being in a strange country, and your wife, Don Carlos, is so very amiable.”

He gave her a cordial smile, and Marguerite saw that he matched his wife for fine looks and kind eyes. Despite the stark formality of his black velvet clothes and thick white hair and beard, his glance was most gentle when he looked at Dona Elena. “She is indeed amiable, Señorita Dumas, and I am grateful she has found a new friend here. It is not easy for her to be so far from her son at this time. I’m happy for any distraction you can provide for her. Perhaps you would do us the honour of joining us for a small card party in our apartment after the banquet?”

“Oh, yes, do say you will come, Señorita Dumas,” Dona Elena urged. “It is only a few friends for a hand of primero, and will be much quieter than these great feasts. I would enjoy knowing you better.”

“Merci, Dona Elena. I happily accept your invitation.”

That was even easier than she expected. Marguerite sat back, satisfied with her progress. Then she felt a sharp, stabbing prickle on the back of her neck, like a sewing needle jabbing at her skin. She laid her fingers over the spot, under her hair, and glanced down the table to find Nicolai watching her.

For an instant, she caught him unaware, and his mask of merriment was down. His face was hard and serious as he looked at her, his eyes hooded. Even thus she could feel the force of them, like celestial blue daggers. She felt caught, pinned in place, unable to move or think. The entire vast, crowded hall vanished, narrowed to that one point—just him.

He grinned at her, breaking the spell, and lifted his goblet to her in mocking salute. As the room widened out again, she saw that he sat next to one of Dona Elena’s ladies, a young woman who stared up at him with shining adoration writ large on her pretty, heart-shaped face.

Marguerite turned away, taking a large gulp of her wine. It was fine stuff, a golden sack from Provence, that even her father, who firmly believed only his home in Champagne could produce truly fine wine, would not have scorned. Yet she hardly even tasted it.

Across the table, Dona Elena caught her eye and gave her a wink. “My plan is working!” she mouthed.

She could say nothing else, though, for a procession arrived bearing an enormous subtlety for the courtiers’ applause. It was a rendition of Greenwich Palace itself all in sugar and almond paste, its turrets and courtyards and windows, even a river of blue marzipan dotted with tiny boats and barges. Yet, like the wine, Marguerite did not fully appreciate the fine artistry. Her skin still prickled, and it took all her strength not to turn back to Nicolai. Not to stare at him like a dull-witted peasant girl.

The subtlety was presented to King Henry and Queen Katherine, and followed by more practical fare of meats, fish and stewed vegetables.

Roger Tilney laid a tender morsel of duck with orange sauce on her plate. “How are you enjoying your time in England thus far, Mademoiselle Dumas?” he asked.

Marguerite smiled at him, and speared the duck with her eating knife. She imagined the blade entering Nicolai’s golden flesh, and it gave her a childish flash of satisfaction. “Very well, Master Tilney. You were right, Greenwich is endlessly fascinating.”

“I am glad you find it so. I hear of nothing else but ‘the beautiful Mademoiselle Dumas’ everywhere I go!”

Marguerite laughed, reaching for a bite of the soft white manchet bread. “I doubt that. Perhaps two people have said that, including yourself. But I do hear that I have you to thank for one thing. Thank—or curse.”

“I am most intrigued. Ladies have surely cursed me before, but rarely on such short acquaintance. What must I beg pardon for?”

“For recommending me to the Master of Revels for his pageants.”

Tilney laughed. “I merely suggested that it would be a fine gesture to include some of the French ladies. Your beauty and sweetness recommended themselves.”

“I am scarcely sweet, Master Tilney! In fact, I have often been told quite the opposite.”

“Mademoiselle Dumas, methinks you protest too much.” He reached for a sugar wafer from one of the silver platters, offering it to her with a flourish. “These rare delicacies could not be more agreeable than you.”

Marguerite accepted it with a smile, but the delicate flavor turned dry in her mouth as she saw that Nicolai still laughed with his pretty Spanish companion. Her sweetness no doubt far surpassed any honey or sugar.

The banquet went on for what seemed like hours, a succession of artichokes in cream sauce, whole pigs stuffed with spiced apples, swan and peacock, lamb dressed with mint, and sweetmeats coloured pink and pale green and dusted with more sparkling sugar.

As the wine flowed, the shrill laughter grew, until Marguerite could scarcely hear above the hum in her head. She ate little and drank less, her smile growing more pained as the revelry went on. Would her face simply crack, like one of the statues in the garden? The marble of her skin corroding under the bombardment of rain and laughter, flaking away until she was nothing at all, just a handful of white dust.

At last, the platters and cloths were carried away, the curved table pushed forward so there could be dancing in its hollowed space. The musicians, who had been playing sweet madrigals practically unnoticed during the feasting, struck up a stately pavane. King Henry led the dance with his daughter, her tiny hand in his giant paw.

Princess Mary was a graceful little thing, Marguerite observed, pointing her toe, turning with a flourish of her wrist. Her thin face was solemn with concentration, but her father beamed down at her. Queen Katherine watched it all with a serene smile. Would the princess truly marry the Duc d’Orleans one day, and be a credit to the French royal family? Marguerite could not yet say. It was early days yet in the treaty negotiations, and Princess Mary seemed so solemn, so—Spanish. But it could be an important, and long-lasting, alliance for François and Henry both.

As the music ended, Henry lifted Mary high, twirling her around as he laughed. “You behold here, gentles, my pearl of the world!” he announced. Amid applause, the princess bowed prettily.