полная версия

полная версияThe Naval War of 1812

[Illustration: Wasp vs. Frolic: a contemporary painting by Thomas Birch, believed to have been done for the Wasp's captain, James Biddle. (Courtesy Peabody Museum of Salem)]

The two vessels were practically of equal force. The loss of the Frolic's main-yard had merely converted her into a brigantine, and, as the roughness of the sea made it necessary to fight under very short canvas, her inferiority in men was fully compensated for by her superiority in metal. She had been desperately defended; no men could have fought more bravely than Captain Whinyates and his crew. On the other hand, the Americans had done their work with a coolness and skill that could not be surpassed; the contest had been mainly one of gunnery, and had been decided by the greatly superior judgment and accuracy with which they fired. Both officers and crew had behaved well; Captain Jones particularly mentions Lieutenant Claxton, who, though too ill to be of any service, persisted in remaining on deck throughout the engagement.

The Wasp was armed with 2 long 12's and 16 32-pound carronades; the Frolic with 2 long 6's, 16 32-pound carronades, and 1 shifting 12-pound carronade.

COMPARATIVE FORCE.

Tons. No. Guns. Weight Metal. Crews. Loss. Wasp 450 9 250 135 10 Frolic 467 10 274 110 90

Vice-Admiral Jurien de la Gravière comments on this action as follows [Footnote: "Guerres Maritimes," ii, 287 (Septième Édition, Paris, 1881).]:

DIAGRAM [Footnote: It is difficult to reconcile the accounts of the manoeuvres in this action. James says "larboard" where Cooper says "starboard"; one says the Wasp wore, the other says that she could not do so, etc.]

[Illustration: Shows the paths of the Wasp and the Frolic during their battle and the positions of the ships at various times during the battle from 11.32 to 12.15]

"The American fire showed itself to be as accurate as it was rapid. On occasions when the roughness of the sea would seem to render all aim excessively uncertain, the effects of their artillery were not less murderous than under more advantageous conditions. The corvette Wasp fought the brig Frolic in an enormous sea, under very short canvas, and yet, forty minutes after the beginning of the action, when the two vessels came together, the Americans who leaped aboard the brig found on the deck, covered with dead and dying, but one brave man, who had not left the wheel, and three officers, all wounded, who threw down their swords at the feet of the victors." Admiral de la Gravière's criticisms are especially valuable, because they are those of an expert, who only refers to the war of 1812 in order to apply to the French navy the lessons which it teaches, and who is perfectly unprejudiced. He cares for the lesson taught, not the teacher, and is quite as willing to learn from the defeat of the Chesapeake as from the victories of the Constitution—while most American critics only pay heed to the latter.

The characteristics of the action are the practical equality of the contestants in point of force and the enormous disparity in the damage each suffered; numerically, the Wasp was superior by 5 per cent., and inflicted a ninefold greater loss.

Captain Jones was not destined to bring his prize into port, for a few hours afterward the Poictiers, a British 74, Captain John Poer Beresford, hove in sight. Now appeared the value of the Frolic's desperate defence; if she could not prevent herself from being captured, she had at least ensured her own recapture, and also the capture of the foe. When the Wasp shook out her sails they were found to be cut into ribbons aloft, and she could not make off with sufficient speed. As the Poictiers passed the Frolic, rolling like a log in the water, she threw a shot over her, and soon overtook the Wasp. Both vessels were carried into Bermuda. Captain Whinyates was again put in command of the Frolic. Captain Jones and his men were soon exchanged; 25,000 dollars prize-money was voted them by Congress, and Captain and Lieutenant Biddle were both promoted, the former receiving the captured ship Macedonian. Unluckily the blockade was too close for him to succeed in getting out during the remainder of the war.

On Oct. 8th Commodore Rodgers left Boston on his second cruise, with the President, United States, Congress, and Argus, [Footnote: Letter of Commodore Rodgers. Jan. 1. 1813.] leaving the Hornet in port. Four days out, the United States and Argus separated, while the remaining two frigates continued their cruise together. The Argus, [Footnote: Letter of Capt. Arthur Sinclair, Jan. 4, 1813.] Captain Sinclair, cruised to the eastward, making prizes of 6 valuable merchant-men, and returned to port on January 3d. During the cruise she was chased for three days and three nights (the latter being moonlight) by a British squadron, and was obliged to cut away her boats and anchors and start some of her water. But she saved her guns, and was so cleverly handled that during the chase she actually succeeded in taking and manning a prize, though the enemy got near enough to open fire as the vessels separated. Before relating what befell the United States, we shall bring Commodore Rodgers' cruise to an end.

On Oct. 10th the Commodore chased, but failed to overtake, the British frigate Nymphe, 38, Captain Epworth. On the 18th, off the great Bank of Newfoundland, he captured the Jamaica packet Swallow, homeward bound, with 200,000 dollars in specie aboard. On the 31st, at 9 A. M., lat. 33° N., long. 32° W., his two frigates fell in with the British frigate Galatea, 36, Captain Woodley Losack, convoying two South Sea ships, to windward. The Galatea ran down to reconnoitre, and at 10 A. M., recognizing her foes, hauled up on the starboard tack to escape. The American frigates made all sail in chase, and continued beating to windward, tacking several times, for about three hours. Seeing that she was being overhauled, the Galatea now edged away to get on her best point of sailing; at the same moment one of her convoy, the Argo, bore up to cross the hawse of her foes, but was intercepted by the Congress, who lay to to secure her. Meanwhile the President kept after the Galatea; she set her top-mast, top-gallant mast and lower studding-sails, and when it was dusk had gained greatly upon her. But the night was very dark, the President lost sight of the chase, and, toward midnight, hauled to the wind to rejoin her consort. The two frigates cruised to the east as far as 22° W., and then ran down to 17° N.; but during the month of November they did not see a sail. They had but slightly better luck on their return toward home. Passing 120 miles north of Bermuda, and cruising a little while toward the Virginia capes, they reentered Boston on Dec. 31st, having made 9 prizes, most of them of little value.

When four days out, on Oct. 12th, Commodore Decatur had separated from the rest of Rodgers' squadron and cruised east; on the 25th, in lat. 29° N., and long. 29° 30' W. while going close-hauled on the port tack, with the wind fresh from the S. S. E., a sail was descried on the weather beam, about 12 miles distant. [Footnote: Official letter of Commodore Decatur, Oct. 30. 1812.] This was the British 38-gun frigate Macedonian, Captain John Surnam Carden. She was not, like the Guerrière, an old ship captured from the French, but newly built of oak and larger than any American 18-pounder frigate; she was reputed (very wrongfully) to be a "crack ship." According to Lieut. David Hope, "the state of discipline on board was excellent; in no British ship was more attention paid to gunnery. Before this cruise, the ship had been engaged almost every day with the enemy; and in time of peace the crew were constantly exercised at the great guns." [Footnote: Marshall's "Naval Biography," vol. iv, p. 1018.] How they could have practised so much and learned so little is certainly marvellous.

The Macedonian set her foretop-mast and top-gallant studdings sails and bore away in chase, [Footnote: Capt. Carden to Mr. Croker, Oct. 28, 1812.] edging down with the wind a little aft the starboard beam. Her first lieutenant wished to continue on this course and pass down ahead of the United States, [Footnote: James, vi. 165.] but Capt. Carden's over-anxiety to keep the weather-gage lost him this opportunity of closing. [Footnote: Sentence of Court-martial held on the San Domingo, 74. at the Bermudas. May 27, 1812.] Accordingly he hauled by the wind and passed way to windward of the American. As Commodore Decatur got within range, he eased off and fired a broadside, most of which fell short [Footnote: Marshall, iv, 1080.]; he then kept his luff, and, the next time he fired, his long 24's told heavily, while he received very little injury himself. [Footnote: Cooper, 11, 178.] The fire from his main-deck (for he did not use his carronades at all for the first half hour) [Footnote: Letter of Commodore Decatur.] was so very rapid that it seemed as if the ship was on fire; his broadsides were delivered with almost twice the rapidity of those of the Englishman. [Footnote: James, vi, 169.] The latter soon found he could not play at long bowls with any chance of success; and, having already erred either from timidity or bad judgment, Captain Carden decided to add rashness to the catalogue of his virtues. Accordingly he bore up, and came down end on toward his adversary, with the wind on his port quarter. The States now (10.15) laid her main-topsail aback and made heavy play with her long guns, and, as her adversary came nearer, with her carronades also.

[Illustration: Shows the paths of the United States and the Macedonian during their battle and the positions of the ships at various times during the battle from 09.45 to 11.15]

The British ship would reply with her starboard guns, hauling up to do so; as she came down, the American would ease off, run a little way and again come to, keeping up a terrific fire. As the Macedonian bore down to close, the chocks of all her forecastle guns (which were mounted on the outside) were cut away [Footnote: Letter of Captain Carden.]; her fire caused some damage to the American's rigging, but hardly touched her hull, while she herself suffered so heavily both alow and aloft that she gradually dropped to leeward, while the American fore-reached on her. Finding herself ahead and to windward, the States tacked and ranged up under her adversary's lee, when the latter struck her colors at 11.15, just an hour and a half after the beginning of the action. [Footnote: Letter of Commodore Decatur.]

[Illustration: Captain Stephen Decatur: a charcoal drawing done in 1809 by Charles B.J.F. St.-Memin. (Courtesy Library of Congress)]

The United States had suffered surprisingly little; what damage had been done was aloft. Her mizzen top-gallant mast was cut away, some of the spars were wounded, and the rigging a good deal cut; the hull was only struck two or three times. The ships were never close enough to be within fair range of grape and musketry, [Footnote: Letter of Commodore Decatur.] and the wounds were mostly inflicted by round shot and were thus apt to be fatal. Hence the loss of the Americans amounted to Lieutenant John Messer Funk (5th of the ship) and six seamen killed or mortally wounded, and only five severely and slightly wounded.

The Macedonian, on the other hand, had received over a hundred shot in her hull, several between wind and water; her mizzen-mast had gone by the board; her fore—and maintop-masts had been shot away by the caps, and her main-yard in the slings; almost all her rigging was cut away (only the fore-sail being left); on the engaged side all of her carronades but two, and two of her main-deck guns, were dismounted. Of her crew 43 were killed and mortally wounded, and 61 (including her first and third lieutenants) severely and slightly wounded. [Footnote: Letter of Captain Carden.] Among her crew were eight Americans (as shown by her muster-roll); these asked permission to go below before the battle, but it was refused by Captain Carden, and three were killed during the action. James says that they were allowed to go below, but this is untrue; for if they had, the three would not have been slain. The others testified that they had been forced to fight, and they afterward entered the American service—the only ones of the Macedonian's crew who did, or who were asked to.

The Macedonian had her full complement of 301 men; the States had, by her muster-roll of October 20th, 428 officers, petty officers, seamen, and boys, and 50 officers and privates of marines, a total of 478 (instead of 509 as Marshall in his "Naval Biography" makes it).

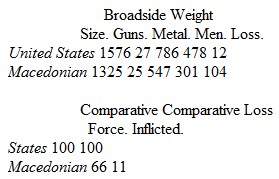

COMPARATIVE FORCE.

That is, the relative force being about as three is to two, [Footnote: I have considered the United States as mounting her full allowance of 54 guns; but it is possible that she had no more than 49. In Decatur's letter of challenge of Jan. 17, 1814 (which challenge, by the way, was a most blustering affair, reflecting credit neither on Decatur, nor his opponent, Captain Hope, nor on any one else, excepting Captain Stackpole of H. M. S. Statira), she is said to have had that number; her broadside would then be 15 long 24's below, 1 long 24, 1 12-pound, and 8 42-pound carronades above. Her real broadside weight of metal would thus be about 680 lbs., and she would be superior to the Macedonian in the proportion of 5 to 4. But it is possible that Decatur had landed some of his guns in 1813, as James asserts; and though I am not at all sure of this, I have thought it best to be on the safe side in describing his force.] the damage done was as nine to one!

Of course, it would have been almost impossible for the Macedonian to conquer with one third less force; but the disparity was by no means sufficient to account for the ninefold greater loss suffered, and the ease and impunity with which the victory was won. The British sailors fought with their accustomed courage, but their gunnery was exceedingly poor; and it must be remembered that though the ship was bravely fought, still the defence was by no means so desperate as that made by the Essex or even the Chesapeake, as witnessed by their respective losses. The Macedonian, moreover, was surrendered when she had suffered less damage than either the Guerrière or Java. The chief cause of her loss lay in the fact that Captain Carden was a poor commander. The gunnery of the Java, Guerrière, and Macedonian was equally bad; but while Captain Lambert proved himself to be as able as he was gallant, and Captain Dacres did nearly as well, Captain Carden, on the other hand, was first too timid, and then too rash, and showed bad judgment at all times. By continuing his original course he could have closed at once; but he lost his chance by over-anxiety to keep the weather-gage, and was censured by the court-martial accordingly. Then he tried to remedy one error by another, and made a foolishly rash approach. A very able and fair-minded English writer says of this action: "As a display of courage the character of the service was nobly upheld, but we would be deceiving ourselves were we to admit that the comparative expertness of the crews in gunnery was equally satisfactory. Now, taking the difference of effect as given by Captain Carden, we must draw this conclusion—that the comparative loss in killed and wounded (104 to 12), together with the dreadful account he gives of the condition of his own ship, while he admits that the enemy's vessel was in comparatively good order, must have arisen from inferiority in gunnery as well as in force." [Footnote: Lord Howard Douglass, "Naval Gunnery." p. 525]

On the other hand, the American crew, even according to James, were as fine a set of men as ever were seen on shipboard. Though not one fourth were British by birth, yet many of them had served on board British ships of war, in some cases voluntarily, but much more often because they were impressed. They had been trained at the guns with the greatest care by Lieutenant Allen. And finally Commodore Decatur handled his ship with absolute faultlessness. To sum up: a brave and skilful crew, ably commanded, was matched against an equally brave but unskilful one, with an incompetent leader; and this accounts for the disparity of loss being so much greater than the disparity in force.

At the outset of this battle the position of the parties was just the reverse of that in the case of the Constitution and Guerrière: the Englishman had the advantage of the wind, but he used it in a very different manner from that in which Captain Hull had done. The latter at once ran down to close, but manoeuvred so cautiously that no damage could be done him till he was within pistol shot. Captain Carden did not try to close till after fatal indecision, and then made the attempt so heedlessly that he was cut to pieces before he got to close quarters. Commodore Decatur, also, manoeuvred more skilfully than Captain Dacres, although the difference was less marked between these two. The combat was a plain cannonade; the States derived no advantage from the superior number of her men, for they were not needed. The marines in particular had nothing whatever to do, while they had been of the greatest service against the Guerrière. The advantage was simply in metal, as 10 is to 7. Lord Howard Douglass' criticisms on these actions seem to me only applicable in part. He says (p. 524): "The Americans would neither approach nor permit us to join in close battle until they had gained some extraordinary advantage from the superior faculties of their long guns in distant cannonade, and from the intrepid, uncircumspect, and often very exposed approach of assailants who had long been accustomed to contemn all manoeuvring. Our vessels were crippled in distant cannonade from encountering rashly the serious disadvantage of making direct attacks; the uncircumspect gallantry of our commanders led our ships unguardedly into the snares which wary caution had spread."

These criticisms are very just as regards the Macedonian, and I fully agree with them (possibly reserving the right to doubt Captain Carden's gallantry, though readily admitting his uncircumspection). But the case of the Guerrière differed widely. There the American ship made the attack, while the British at first avoided close combat; and, so far from trying to cripple her adversary by a distant cannonade, the Constitution hardly fired a dozen times until within pistol shot. This last point is worth mentioning, because in a work on "Heavy Ordnance," by Captain T. F. Simmons, R. A. (London, 1837), it is stated that the Guerrière received her injuries before the closing, mentioning especially the "thirty shot below the water-line"; whereas, by the official accounts of both commanders, the reverse was the case. Captain Hull, in his letter, and Lieutenant Morris, (in his autobiography) say they only fired a few guns before closing; and Captain Dacres, in his letter, and Captain Brenton, in his "History," say that not much injury was received by the Guerrière until about the time the mizzen-mast fell, which was three or four minutes after close action began.

Lieutenant Allen was put aboard the Macedonian as prize-master; he secured the fore- and main-masts and rigged a jury mizzen-mast, converting the vessel into a bark. Commodore Decatur discontinued his cruise to convoy his prize back to America; they reached New London Dec. 4th. Had it not been for the necessity of convoying the Macedonian, the States would have continued her cruise, for the damage she suffered was of the most trifling character.

Captain Garden stated (in Marshall's "Naval Biography") that the States measured 1,670 tons, was manned by 509 men, suffered so from shot under water that she had to be pumped out every watch, and that two eighteen-pound shot passed in a horizontal line through her main-masts; all of which statements were highly creditable to the vividness of his imagination. The States measured but 1,576 tons (and by English measurement very much less), had 478 men aboard, had not been touched by a shot under water-line, and her lower masts were unwounded. James states that most of her crew were British, which assertion I have already discussed; and that she had but one boy aboard, and that he was seventeen years old,—in which case 29 others, some of whom (as we learn from the "Life of Decatur") were only twelve, must have grown with truly startling rapidity during the hour and a half that the combat lasted.

During the twenty years preceding 1812 there had been almost incessant warfare on the ocean, and although there had been innumerable single conflicts between French and English frigates, there had been but one case in which the French frigate, single-handed, was victorious. This was in the year 1805 when the Milan captured the Cleopatra. According to Troude, the former threw at a broadside 574 pounds (actual), the latter but 334; and the former lost 35 men out of her crew of 350, the latter 58 out of 200. Or, the forces being as 100 to 58, the loss inflicted was as 100 to 60; while the States' force compared to the Macedonian's being as 100 to 66, the loss she inflicted was as 100 to 11.

British ships, moreover, had often conquered against odds as great; as, for instance, when the Sea Horse captured the great Turkish frigate Badere-Zaffer; when the Astrea captured the French frigate Gloire, which threw at a broadside 286 pounds of shot, while she threw but 174; and when, most glorious of all, Lord Dundonald, in the gallant little Speedy, actually captured the Spanish xebec Gamo of over five times her own force! Similarly, the corvette Comus captured the Danish frigate Fredrickscoarn, the brig Onyx captured the Dutch sloop Manly, the little cutter Thorn captured the French Courier-National, and the Pasly the Spanish Virgin; while there had been many instances of drawn battles between English 12-pound frigates and French or Spanish 18-pounders.

Captain Hull having resigned the command of the Constitution, she was given to Captain Bainbridge, of the Constellation, who was also entrusted with the command of the Essex and Hornet. The latter ship was in the port of Boston with the Constitution, under the command of Captain Lawrence. The Essex was in the Delaware, and accordingly orders were sent to Captain Porter to rendezvous at the Island of San Jago; if that failed several other places were appointed, and if, after a certain time, he did not fall in with his commodore he was to act at his own discretion.

[Illustration: Captain William Bainbridge: a portrait by John Wesley Jarvis, circa 1814. (Courtesy U.S. Naval Academy Museum)]

On October 26th the Constitution and Hornet sailed, touched at the different rendezvous, and on December 13th arrived off San Salvador, where Captain Lawrence found the Bonne Citoyenne, 18, Captain Pitt Barnaby Greene. The Bonne Citoyenne was armed with 18 32-pound carronades and 2 long nines, and her crew of 150 men was exactly equal in number to that of the Hornet; the latter's short weight in metal made her antagonist superior to her in about the same proportion that she herself was subsequently superior to the Penguin, or, in other words, the ships were practically equal. Captain Lawrence now challenged Captain Greene to single fight, giving the usual pledges that the Constitution should not interfere. The challenge was not accepted for a variety of reasons; among others the Bonne Citoyenne was carrying home half a million pounds in specie. [Footnote: Brenton and James both deny that Captain Greene was blockaded by the Hornet, and claim that he feared the Constitution. James says (p. 275) that the occurrence was one which "the characteristic cunning of Americans turned greatly to their advantage"; and adds that Lawrence only sent the challenge because "it could not be accepted," and so he would "suffer no personal risk." He states that the reason it was sent, as well as the reason that it was refused, was because the Constitution was going to remain in the offing and capture the British ship if she proved conqueror. It is somewhat surprising that even James should have had the temerity to advance such arguments. According to his own account (p. 277) the Constitution left for Boston on Jan. 6th, and the Hornet remained blockading the Bonne Citoyenne till the 24th, when the Montagu, 74, arrived. During these eighteen days there could have been no possible chance of the Constitution or any other ship interfering, and it is ridiculous to suppose that any such fear kept Captain Greene from sailing out to attack his foe. No doubt Captain Greene's course was perfectly justifiable, but it is curious that with all the assertions made by James as to the cowardice of the Americans, this is the only instance throughout the war in which a ship of either party declined a contest with an antagonist of equal force (the cases of Commodore Rodgers and Sir George Collier being evidently due simply to an overestimate of the opposing ships.)] Leaving the Hornet to blockade her, Commodore Bainbridge ran off to the southward, keeping the land in view.