полная версия

полная версияThe Naval War of 1812

At 9 A. M., Dec. 29, 1812, while the Constitution was running along the coast of Brazil, about thirty miles offshore in latitude 13° 6' S., and longitude 31° W., two strange sail were made, [Footnote: Official letter of Commodore Bainbridge, Jan. 3, 1813.] inshore and to windward. These were H. B. M. frigate Java, Captain Lambert, forty-eight days out of Spithead, England, with the captured ship William in company. Directing the latter to make for San Salvador, the Java bore down in chase of the Constitution. [Footnote: Official letter of Lieutenant Chads, Dec. 31, 1812.] The wind was blowing light from the N.N.E., and there was very little sea on. At 10 the Java made the private signals, English, Spanish, and Portuguese in succession, none being answered; meanwhile the Constitution was standing up toward the Java on the starboard tack; a little after 11 she hoisted her private signal, and then, being satisfied that the strange sail was an enemy, she wore and stood off toward the S.E., to draw her antagonist away from the land, [Footnote: Log of the Constitution.] which was plainly visible. The Java hauled up, and made sail in a parallel course, the Constitution bearing about three points on her lee bow. The Java gained rapidly, being much the swifter.

At 1.30 the Constitution luffed up, shortened her canvas to top-sails, top-gallant sails, jib, and spanker, and ran easily off on the port tack, heading toward the southeast; she carried her commodore's pendant at the main, national ensigns at the mizzenpeak and main top-gallant mast-head, and a Jack at the fore. The Java also had taken in the main-sail and royals, and came down in a lasking course on her adversary's weather-quarter, [Footnote: Lieutenant Chads' Address to the Court-martial, April 23, 1813.] hoisting her ensign at the mizzen-peak, a union Jack at the mizzen top-gallant mast-head, and another lashed to the main-rigging. At 2 P. M., the Constitution fired a shot ahead of her, following it quickly by a broadside, [Footnote: Commodore Bainbridge's letter.] and the two ships began at long bowls, the English firing the lee or starboard battery while the Americans replied with their port guns. The cannonade was very spirited on both sides, the ships suffering about equally. The first broadside of the Java was very destructive, killing and wounding several of the Constitution's crew. The Java kept edging down, and the action continued, with grape and musketry in addition; the swifter British ship soon forereached and kept away, intending to wear across her slower antagonist's bow and rake her; but the latter wore in the smoke, and the two combatants ran off to the westward, the Englishman still a-weather and steering freer than the Constitution, which had luffed to close. [Footnote: Log of the Constitution.] The action went on at pistol-shot distance. In a few minutes, however, the Java again forged ahead, out of the weight of her adversary's fire, and then kept off, as before, to cross her bows; and, as before, the Constitution avoided this by wearing, both ships again coming round with their heads to the east, the American still to leeward. The Java kept the weather-gage tenaciously, forereaching a little, and whenever the __Constitution_ luffed up to close, [Footnote: Log of Constitution.] the former tried to rake her. But her gunnery was now poor, little damage being done by it; most of the loss the Americans suffered was early in the action. By setting her foresail and main-sail the Constitution got up close on the enemy's lee beam, her fire being very heavy and carrying away the end of the Java's bowsprit and her jib-boom. [Footnote: Lieutenant Chads' letter.] The Constitution forged ahead and repeated her former manoeuvre, wearing in the smoke. The Java at once hove in stays, but owing to the loss of head-sail fell off very slowly, and the American frigate poured a heavy raking broadside into her stern, at about two cables' length distance. The Java replied with her port guns as she fell off. [Footnote: Lieutenant Chads' letter.] Both vessels then bore up and ran off free, with the wind on the port quarter; the Java being abreast and to windward of her antagonist, both with their heads a little east of south. The ships were less than a cable's length apart, and the Constitution inflicted great damage while suffering very little herself. The British lost many men by the musketry of the American topmen, and suffered still more from the round and grape, especially on the forecastle, [Footnote: Testimony of Christopher Speedy, in minutes of the Court-martial on board H. M. S. Gladiator, at Portsmouth, April 23, 1813] many marked instances of valor being shown on both sides. The Java's masts were wounded and her rigging cut to pieces, and Captain Lambert then ordered her to be laid aboard the enemy, who was on her lee beam. The helm was put a-weather, and the Java came down for the Constitution's main-chains. The boarders and marines gathered in the gangways and on the forecastle, the boatswain having been ordered to cheer them up with his pipe that they might make a clean spring. [Footnote: Testimony of James Humble, in do., do.] The Americans, however, raked the British with terrible effect, cutting off their main top-mast above the cap, and their foremast near the cat harpings. [Footnote: Log of Constitution.] The stump of the Java's bowsprit got caught in the Constitution's mizzen-rigging, and before it got clear the British suffered still more.

[Illustration: Constitution vs. Java: a comptemporary American engraving done under the supervision of a witness to the action. (Courtesy Beverley R. Robinson Collection, U.S. Naval Academy Museum)]

Finally the ships separated, the Java's bowsprit passing over the taffrail of the Constitution; the latter at once kept away to avoid being raked. The ships again got nearly abreast, but the Constitution, in her turn, forereached; whereupon Commodore Bainbridge wore, passed his antagonist, luffed up under his quarter, raked him with the starboard guns, then wore, and recommenced the action with his port broadside at about 3.10. Again the vessels were abreast, and the action went on as furiously as ever. The wreck of the top hamper on the Java lay over her starboard side, so that every discharge of her guns set her on fire, [Footnote: Lieut. Chads' Address.] and in a few minutes her able and gallant commander was mortally wounded by a ball fired by one of the American main-top-men. [Footnote: Surgeon J. C. Jones' Report.] The command then devolved on the first lieutenant, Chads, himself painfully wounded. The slaughter had been terrible, yet the British fought on with stubborn resolution, cheering lustily. But success was now hopeless, for nothing could stand against the cool precision of the Yankee fire. The stump of the Java's foremast was carried away by a double-headed shot, the mizzen-mast fell, the gaff and spanker boom were shot away, also the main-yard, and finally the ensign was cut down by a shot, and all her guns absolutely silenced; when at 4.05 the Constitution, thinking her adversary had struck, [Footnote: Log of the Constitution (as given in Bainbridge's letter).] ceased firing, hauled aboard her racks, and passed across her adversary's bows to windward, with her top-sails, jib, and spanker set. A few minutes afterward the Java's main-mast fell, leaving her a sheer hulk. The Constitution assumed a weatherly position, and spent an hour in repairing damages and securing her masts; then she wore and stood toward her enemy, whose flag was again flying, but only for bravado, for as soon as the Constitution stood across her forefoot she struck. At 5.25 she was taken possession of by Lieutenant Parker, 1st of the Constitution, in one of the latter's only two remaining boats.

The American ship had suffered comparatively little. But a few round shot had struck her hull, one of which carried away the wheel; one 18-pounder went through the mizzen-mast; the fore-mast, main-top-mast, and a few other spars were slightly wounded, and the running rigging and shrouds were a good deal cut; but in an hour she was again in good fighting trim. Her loss amounted to 8 seamen and 1 marine killed; the 5th lieutenant, John C. Alwyn, and 2 seamen, mortally, Commodore Bainbridge and 12 seamen, severely, and 7 seamen and 2 marines, slightly wounded; in all 12 killed and mortally wounded, and 22 wounded severely and slightly. [Footnote: Report of Surgeon Amos A. Evans.]

"The Java sustained unequalled injuries beyond the Constitution," says the British account. [Footnote: "Naval Chronicle," xxix. 452.] These have already been given in detail; she was a riddled and entirely dismasted hulk. Her loss (for discussion of which see farther on) was 48 killed (including Captain Henry Lambert, who died soon after the close of the action, and five midshipmen), and 102 wounded, among them Lieutenant Henry Ducie Chads, Lieutenant of Marines David Davies, Commander John Marshall, Lieut. James Saunders, the boatswain. James Humble, master, Batty Robinson, and four midshipmen.

In this action both ships displayed equal gallantry and seamanship. "The Java," says Commodore Bainbridge, "was exceedingly well handled and bravely fought. Poor Captain Lambert was a distinguished and gallant officer, and a most worthy man, whose death I sincerely regret." The manoeuvring on both sides was excellent; Captain Lambert used the advantage which his ship possessed in her superior speed most skilfully, always endeavoring to run across his adversary's bows and rake him when he had forereached, and it was only owing to the equal skill which his antagonist displayed that he was foiled, the length of the combat being due to the number of evolutions. The great superiority of the Americans was in their gunnery. The fire of the Java was both less rapid and less well directed than that of her antagonist; the difference of force against her was not heavy, being about as ten is to nine, and was by no means enough to account for the almost fivefold greater loss she suffered.

[Illustration: This differs somewhat from the English diagram: the American officers distinctly assert that the Java kept the weather-gage in every position.]

The foregoing is a diagram of the battle. It differs from both of the official accounts, as these conflict greatly both as to time and as regards some of the evolutions. I generally take the mean in cases of difference; for example, Commodore Bainbridge's report makes the fight endure but 1 hour and 55 minutes, Lieutenant Chads' 2 hours and 25 minutes: I have made it 2 hours and 10 minutes, etc., etc.

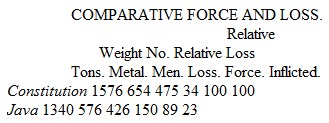

The tonnage and weight of metal of the combatants have already been stated; I will give the complements shortly. The following is the

In hardly another action the war do the accounts of the respective forces differ so widely; the official British letter makes their total of men at the beginning of the action 377, of whom Commodore Bainbridge officially reports that he paroled 378! The British state their loss in killed and mortally wounded at 24; Commodore Bainbridge reports that the dead alone amounted to nearly 60! Usually I have taken each commander's account of his own force and loss, and I should do so now if it were not that the British accounts differ among themselves, and whenever they relate to the Americans, are flatly contradicted by the affidavits of the latter's officers. The British first handicap themselves by the statement that the surgeon of the Constitution was an Irishman and lately an assistant surgeon in the British navy ("Naval Chronicle," xxix, 452); which draws from Surgeon Amos A. Evans a solemn statement in the Boston Gazette that he was born in Maryland and was never in the British navy in his life. Then Surgeon Jones of the Java, in his official report, after giving his own killed and mortally wounded at 24, says that the Americans lost in all about 60, and that 4 of their amputations perished under his own eyes; whereupon Surgeon Evans makes the statement (Niles' Register, vi, p. 35), backed up by affidavits of his brother officers, that in all he had but five amputations, of whom only one died, and that one, a month after Surgeon Jones had left the ship. To meet the assertions of Lieutenant Chads that he began action with but 377 men, the Constitution's officers produced the Java's muster-roll, dated Nov. 17th, or five days after she had sailed, which showed 446 persons, of whom 20 had been put on board a prize. The presence of this large number of supernumeraries on board is explained by the fact that the Java was carrying out Lieutenant-General Hislop, the newly-appointed Governor of Bombay, and his suite, together with part of the crews for the Cornwallis, 74, and gun-sloops Chameleon and Icarus; she also contained stores for those two ships.

Besides conflicting with the American reports, the British statements contradict one another. The official published report gives but two midshipmen as killed; while one of the volumes of the "Naval Chronicle" (vol. xxix, p. 452) contains a letter from one of the Java's lieutenants, in which he states that there were five. Finally, Commodore Bainbridge found on board the Constitution, after the prisoners had left, a letter from Lieutenant H. D. Cornick, dated Jan. 1, 1813, and addressed to Lieutenant Peter V. Wood, 22d Regiment, foot, in which he states that 65 of their men were killed. James ("Naval Occurrences") gets around this by stating that it was probably a forgery; but, aside from the improbability of Commodore Bainbridge being a forger, this could not be so, for nothing would have been easier than for the British lieutenant to have denied having written it, which he never did. On the other hand, it would be very likely that in the heat of the action, Commodore Bainbridge and the Java's own officers should overestimate the latter's loss. [Footnote: For an account of the shameless corruption then existing in the Naval Administration of Great Britain, see Lord Dundonald's "Autobiography of a seaman." The letters of the commanders were often garbled, as is mentioned by Brenton. Among numerous cases that he gives, may be mentioned the cutting out of the Chevrette, where he distinctly says, "our loss was much greater than was ever acknowledged." (Vol. i, p. 505, edition of 1837.)]

Taking all these facts into consideration, we find 446 men on board the Java by her own muster-list; 378 of these were paroled by Commodore Bainbridge at San Salvador; 24 men were acknowledged by the enemy to be killed or mortally wounded; 20 were absent in a prize, leaving 24 unaccounted for, who were undoubtedly slain.

The British loss was thus 48 men killed and mortally wounded, and 102 wounded severely and slightly. The Java was better handled and more desperately defended than the Macedonian or even the Guerrière. and the odds against her were much smaller; so she caused her opponent greater loss, though her gunnery was no better than theirs.

Lieutenant Parker, prize-master of the Java, removed all the prisoners and baggage to the Constitution, and reported the prize to be in a very disabled state; owing partly to this, but more to the long distance from home and the great danger there was of recapture, Commodore Bainbridge destroyed her on the 31st, and then made sail for San Salvador. "Our gallant enemy," reports Lieutenant Chads, "has treated us most generously"; and Lieutenant-General Hislop presented the Commodore with a very handsome sword as a token of gratitude for the kindness with which he had treated the prisoners.

Partly in consequence of his frigate's injuries, but especially because of her decayed condition, Commodore Bainbridge sailed from San Salvador on Jan. 6, 1813, reaching Boston Feb. 27th, after his four months' cruise. At San Salvador he left the Hornet still blockading the Bonne Citoyenne.

In order "to see ourselves as others see us," I shall again quote from Admiral Jurien de la Gravière, [Footnote "Guerres Maritimes," ii, 284 (Paris, 1881).] as his opinions are certainly well worthy of attention both as to these first three battles, and as to the lessons they teach. "When the American Congress declared war on England in 1812," he says, "it seemed as if this unequal conflict would crush her navy in the act of being born; instead, it but fertilized the germ. It is only since that epoch that the United States has taken rank among maritime powers. Some combats of frigates, corvettes, and brigs, insignificant without doubt as regards material results, sufficed to break the charm which protected the standard of St. George, and taught Europe what she could have already learned from some of our combats, if the louder noise of our defeats had not drowned the glory, that the only invincibles on the sea are good seamen and good artillerists.

"The English covered the ocean with their cruisers when this unknown navy, composed of six frigates and a few small craft hitherto hardly numbered, dared to establish its cruisers at the mouth of the Channel, in the very centre of the British power. But already the Constitution had captured the Guerrière and Java, the United States had made a prize of the Macedonian, the Wasp of the Frolic, and the Hornet of the Peacock. The honor of the new flag was established. England, humiliated, tried to attribute her multiplied reverses to the unusual size of the vessels which Congress had had constructed in 1799, and which did the fighting in 1812. She wished to refuse them the name of frigates, and called them, not without some appearance of reason, disguised line-of-battle ships. Since then all maritime powers have copied these gigantic models, as the result of the war of 1812 obliged England herself to change her naval material; but if they had employed, instead of frigates, cut-down 74's (vaisseaux rasés), it would still be difficult to explain the prodigious success of the Americans. * * *

"In an engagement which terminated in less than half an hour, the English frigate Guerrière, completely dismasted, had fifteen men killed, sixty-three wounded, and more than thirty shot below the water-line. She sank twelve hours after the combat. The Constitution, on the contrary, had but seven men killed and seven wounded, and did not lose a mast. As soon as she had replaced a few cut ropes and changed a few sails, she was in condition, even by the testimony of the British historian, to take another Guerrière. The United States took an hour and a half to capture the Macedonian, and the same difference made itself felt in the damage suffered by the two ships. The Macedonian had her masts shattered, two of her main-deck and all her spar-deck guns disabled; more than a hundred shot had penetrated the hull, and over a third of the crew had suffered by the hostile fire. The American frigate, on the contrary, had to regret but five men killed and seven wounded; her guns had been fired each sixty-six times to the Macedonian's thirty-six. The combat of the Constitution and the Java lasted two hours, and was the most bloody of these three engagements. The Java only struck when she had been razed like a sheer hulk; she had twenty-two men killed and one hundred and two wounded.

* * * * *"This war should be studied with unceasing diligence; the pride of two peoples to whom naval affairs are so generally familiar has cleared all the details and laid bare all the episodes, and through the sneers which the victors should have spared, merely out of care for their own glory, at every step can be seen that great truth, that there is only success for those who know how to prepare it.

* * * * *"It belongs to us to judge impartially these marine events, too much exalted perhaps by a national vanity one is tempted to excuse. The Americans showed, in the War of 1812, a great deal of skill and resolution. But if, as they have asserted, the chances had always been perfectly equal between them and their adversaries, if they had only owed their triumphs to the intrepidity of Hull, Decatur, and Bainbridge, there would be for us but little interest in recalling the struggle. We need not seek lessons in courage outside of our own history. On the contrary, what is to be well considered is that the ships of the United States constantly fought with chances in their favor, and it is on this that the American government should found its true title to glory. * * * The Americans in 1812 had secured to themselves the advantage of a better organization [than the English]."

The fight between the Constitution and the Java illustrates best the proposition, "that there is only success for those who know how to prepare it." Here the odds in men and metal were only about as 10 to 9 in favor of the victors, and it is safe to say that they might have been reversed without vitally affecting the result. In the fight Lambert handled his ship as skilfully as Bainbridge did his; and the Java's men proved by their indomitable courage that they were excellent material. The Java's crew was new shipped for the voyage, and had been at sea but six weeks; in the Constitution's first fight her crew had been aboard of her but five weeks. So the chances should have been nearly equal, and the difference in fighting capacity that was shown by the enormous disparity in the loss, and still more in the damage inflicted, was due to the fact that the officers of one ship had, and the officers of the other had not, trained their raw crews. The Constitution's men were not "picked," but simply average American sailors, as the Java's were average British sailors. The essential difference was in the training.

During the six weeks the Java was at sea her men had fired but six broadsides, of blank cartridges; during the first five weeks the Constitution cruised, her crew were incessantly practised at firing with blank cartridges and also at a target. [Footnote: In looking through the logs of the Constitution, Hornet, etc., we continually find such entries as "beat to quarters, exercised the men at the great guns," "exercised with musketry," "exercised the boarders," "exercised the great guns, blank cartridges, and afterward firing at mark."] The Java's crew had only been exercised occasionally, even in pointing the guns, and when the captain of a gun was killed the effectiveness of the piece was temporarily ruined, and, moreover, the men did not work together. The Constitution's crew were exercised till they worked like machines, and yet with enough individuality to render it impossible to cripple a gun by killing one man. The unpractised British sailors fired at random; the trained Americans took aim. The British marines had not been taught any thing approximating to skirmishing or sharp-shooting; the Americans had. The British sailors had not even been trained enough in the ordinary duties of seamen; while the Americans in five weeks had been rendered almost perfect. The former were at a loss what to do in an emergency at all out of their own line of work; they were helpless when the wreck fell over their guns, when the Americans would have cut it away in a jiffy. As we learn from Commodore Morris' "Autobiography," each Yankee sailor could, at need, do a little carpentering or sail-mending, and so was more self-reliant. The crew had been trained to act as if guided by one mind, yet each man retained his own individuality. The petty officers were better paid than in Great Britain, and so were of a better class of men, thoroughly self-respecting; the Americans soon got their subordinates in order, while the British did not. To sum up: one ship's crew had been trained practically and thoroughly, while the other crew was not much better off than the day it sailed; and, as far as it goes, this is a good test of the efficiency of the two navies.