полная версия

полная версияThe Naval War of 1812

The Constitution's crew showed the most excellent spirit. Officers and men relieved each other regularly, the former snatching their rest any where on deck, the latter sleeping at the guns. Gradually the Constitution drew ahead, but the situation continued most critical. All through the afternoon the British frigates kept towing and kedging, being barely out of gunshot. At 3 P. M. a light breeze sprung up, and blew fitfully at intervals; every puff was watched closely and taken advantage of to the utmost. At 7 in the evening the wind almost died out, and for four more weary hours the worn-out sailors towed and kedged. At 10.45 a little breeze struck the frigate, when the boats dropped alongside and were hoisted up, excepting the first cutter. Throughout the night the wind continued very light, the Belvidera forging ahead till she was off the Constitution's lee beam; and at 4 A. M., on the morning of the 19th, she tacked to the eastward, the breeze being light from the south by east. At 4.20 the Constitution tacked also; and at 5.15 the Aeolus, which had drawn ahead, passed on the contrary tack. Soon afterward the wind freshened so that Captain Hull took in his cutter. The Africa was now so far to leeward as to be almost out of the race; while the five frigates were all running on the starboard tack with every stitch of canvas set. At 9 A. M. an American merchant-man hove in sight and bore down toward the squadron. The Belvidera, by way of decoy, hoisted American colors, when the Constitution hoisted the British flag, and the merchant vessel hauled off. The breeze continued light till noon, when Hull found he had dropped the British frigates well behind; the nearest was the Belvidera, exactly in his wake, bearing W. N. W. 2 1/2 miles distant. The Shannon was on his lee, bearing N. by W. 1/2 W. distant 3 1/2 miles. The other two frigates were five miles off on the lee quarter. Soon afterward the breeze freshened, and "old Ironsides" drew slowly ahead from her foes, her sails being watched and tended with the most consummate skill. At 4 P. M. the breeze again lightened, but even the Belvidera was now four miles astern and to leeward. At 6.45 there were indications of a heavy rain squall, which once more permitted Hull to show that in seamanship he excelled even the able captains against whom he was pitted. The crew were stationed and every thing kept fast till the last minute, when all was clewed up just before the squall struck the ship. The light canvas was furled, a second reef taken in the mizzen top-sail, and the ship almost instantly brought under short sail. The British vessels seeing this began to let go and haul down without waiting for the wind, and were steering on different tacks when the first gust struck them. But Hull as soon as he got the weight of the wind sheeted home, hoisted his fore and main-top gallant sails, and went off on an easy bowline at the rate of 11 knots. At 7.40 sight was again obtained of the enemy, the squall having passed to leeward; the Belvidera, the nearest vessel, had altered her bearings two points to leeward, and was a long way astern. Next came the Shannon; the Guerrière and Aeolus were hull down, and the Africa barely visible. The wind now kept light, shifting occasionally in a very baffling manner, but the Constitution gained steadily, wetting her sails from the sky-sails to the courses. At 6 A. M., on the morning of the 20th the pursuers were almost out of sight; and at 8.15 A. M. they abandoned the chase. Hull at once stopped to investigate the character of two strange vessels, but found them to be only Americans; then, at midday, he stood toward the east, and went into Boston on July 26th.

In this chase Captain Isaac Hull was matched against five British captains, two of whom, Broke and Byron, were fully equal to any in their navy; and while the latter showed great perseverance, good seamanship, and ready imitation, there can be no doubt that the palm in every way belongs to the cool old Yankee. Every daring expedient known to the most perfect seamanship was tried, and tried with success; and no victorious fight could reflect more credit on the conqueror than this three days' chase did on Hull. Later, on two occasions, the Constitution proved herself far superior in gunnery to the average British frigate; this time her officers and men showed that they could handle the sails as well as they could the guns. Hull out-manoeuvred Broke and Byron as cleverly as a month later he out-fought Dacres. His successful escape and victorious fight were both performed in a way that place him above any single ship captain of war.

On Aug. 2d the Constitution made sail from Boston [Footnote: Letter of Capt. Isaac Hull, Aug. 28, 1812.] and stood to the eastward, in hopes of falling in with some of the British cruisers. She was unsuccessful, however, and met nothing. Then she ran down to the Bay of Fundy, steered along the coast of Nova Scotia, and thence toward Newfoundland, and finally took her station off Cape Race in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, where she took and burned two brigs of little value. On the 15th she recaptured an American brig from the British ship-sloop Avenger, though the latter escaped; Capt. Hull manned his prize and sent her in. He then sailed southward, and on the night of the 18th spoke a Salem privateer which gave him news of a British frigate to the south; thither he stood, and at 2 P. M. on the 19th, in lat. 41° 30' N. and 55° W., made out a large sail bearing E. S. E. and to leeward, [Footnote: Letter of Capt. Isaac Hull, Aug. 30, 1812.] which proved to be his old acquaintance, the frigate Guerrière, Captain Dacres. It was a cloudy day and the wind was blowing fresh from the northwest. The Guerrière was standing by the wind on the starboard tack, under easy canvas; [Footnote: Letter of Capt. James R. Dacres, Sept. 7, 1812.] she hauled up her courses, took in her top-gallant sails, and at 4.30 backed her main-top sail. Hull then very deliberately began to shorten sail, taking in top-gallant sails, stay-sails, and flying jib, sending down the royal yards and putting another reef in the top-sails. Soon the Englishman hoisted three ensigns, when the American also set his colors, one at each mast-head, and one at the mizzen peak.

The Constitution now ran down with the wind nearly aft. The Guerrière was on the starboard tack, and at five o'clock opened with her weather-guns, [Footnote: Log of Guerrière.] the shot falling short, then wore round and fired her port broadside, of which two shot struck her opponent, the rest passing over and through her rigging. [Footnote: See in the Naval Archives (Bureau of Navigation) the Constitution's Log-Book (vol. ii, from Feb. 1, 1812, to Dec. 13, 1813). The point is of some little importance because Hull, in his letter, speaks as if both the first broadsides fell short, whereas the log distinctly says that the second went over the ship, except two shot, which came home. The hypothesis of the Guerrière having damaged powder was founded purely on this supposed falling short of the first two broadsides.] As the British frigate again wore to open with her starboard battery, the Constitution yawed a little and fired two or three of her port bow-guns. Three or four times the Guerrière repeated this manoeuvre, wearing and firing alternate broadsides, but with little or no effect, while the Constitution yawed as often to avoid being raked, and occasionally fired one of her bow guns. This continued nearly an hour, as the vessels were very far apart when the action began, hardly any loss or damage being inflicted by either party. At 6.00 the Guerrière bore up and ran off under her top-sails and jib, with the wind almost astern, a little on her port quarter; when the Constitution set her main-top gallant sail and foresail, and at 6.05 closed within half pistol-shot distance on her adversary's port beam. [Footnote: "Autobiography of Commodore Morris" (Annapolis, 1880), p. 164.] Immediately a furious cannonade opened, each ship firing as the guns bore. By the time the ships were fairly abreast, at 6.20, the Constitution shot away the Guerrière's mizzen-mast, which fell over the starboard quarter, knocking a large hole in the counter, and bringing the ship round against her helm. Hitherto she had suffered very greatly and the Constitution hardly at all. The latter, finding that she was ranging ahead, put her helm aport and then luffed short round her enemy's bows, [Footnote: Log of Constitution.] delivering a heavy raking fire with the starboard guns and shooting away the Guerrière's main-yard. Then she wore and again passed her adversary's bows, raking with her port guns. The mizzen-mast of the Guerrière, dragging in the water, had by this time pulled her bow round till the wind came on her starboard quarter; and so near were the two ships that the Englishman's bowsprit passed diagonally over the Constitution's quarter-deck, and as the latter ship fell off it got foul of her mizzen-rigging, and the vessels then lay with the Guerrière's starboard bow against the Constitution's port, or lee quarter-gallery. [Footnote: Cooper, in "Putnam's Magazine." i. 475.] The Englishman's bow guns played havoc with Captain Hull's cabin, setting fire to it; but the flames were soon extinguished by Lieutenant Hoffmann. On both sides the boarders were called away; the British ran forward, but Captain Dacres relinquished the idea of attacking [Footnote: Address of Captain Dacres to the court-martial at Halifax.] when he saw the crowds of men on the American's decks. Meanwhile, on the Constitution, the boarders and marines gathered aft, but such a heavy sea was running that they could not get on the Guerrière. Both sides suffered heavily from the closeness of the musketry fire; indeed, almost the entire loss on the Constitution occurred at this juncture. As Lieutenant Bush, of the marines, sprang upon the taffrail to leap on the enemy's decks, a British marine shot him dead; Mr. Morris, the first Lieutenant, and Mr. Alwyn, the master, had also both leaped on the taffrail, and both were at the same moment wounded by the musketry fire. On the Guerrière the loss was far heavier, almost all the men on the forecastle being picked off. Captain Dacres himself was shot in the back and severely wounded by one of the American mizzen topmen, while he was standing on the starboard forecastle hammocks cheering on his crew [Footnote: James, vi, 144.]; two of the lieutenants and the master were also shot down. The ships gradually worked round till the wind was again on the port quarter, when they separated, and the Guerrière's foremast and main-mast at once went by the board, and fell over on the starboard side, leaving her a defenseless hulk, rolling her main-deck guns into the water. [Footnote: Brenton, v, 51.] At 6.30 the Constitution hauled aboard her tacks, ran off a little distance to the eastward, and lay to. Her braces and standing and running rigging were much cut up and some of the spars wounded, but a few minutes sufficed to repair damages, when Captain Hull stood under his adversary's lee, and the latter at once struck, at 7.00 P. M., [Footnote: Log of the Constitution.] just two hours after she had fired the first shot. On the part of the Constitution, however, the actual fighting, exclusive of six or eight guns fired during the first hour, while closing, occupied less than 30 minutes.

[Illustration: Constitution vs. Guerrière (1): "The Engagement" is the original title of this, the first in a series of four paintings of the action done for Captain Hull by Michele F. Corné. (Courtesy US. Naval Academy Museum)]

[Illustration: Constitution vs. Guerrière (2): "In Action." The Guerrière's mizzenmast goes down. (Courtesy U.S. Naval Academy Museum)]

[Illustration: Constitution vs. Guerrière (3): "Dropping Astern." The Guerrière's mainmast and foremast follow. (Courtesy U.S. Naval Academy Museum)]

[Illustration: Constitution vs. Guerrière (4): "She Fell in the Sea, A Perfect Wreck." The puff of smoke over the Guerrière's bow is from a gun being fired to leeward to signal her surrender, the customary practice when a vessel no longer had a flag to strike. (Courtesy New Haven Historical Society)]

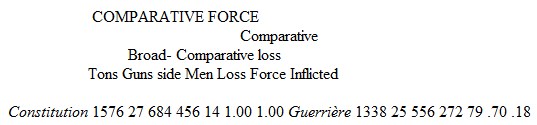

The tonnage and metal of the combatants have already been referred to. The Constitution had, as already said, about 456 men aboard, while of the Guerrière's crew, 267 prisoners were received aboard the Constitution; deducting 10 who were Americans and would not fight, and adding the 15 killed outright, we get 272; 28 men were absent in prizes.

The loss of the Constitution included Lieutenant William S. Bush, of the marines, and six seamen killed, and her first lieutenant, Charles Morris, Master, John C. Alwyn, four seamen, and one marine, wounded. Total, seven killed and seven wounded. Almost all this loss occurred when the ships came foul, and was due to the Guerrière's musketry and the two guns in her bridle-ports.

The Guerrière lost 23 killed and mortally wounded, including her second lieutenant, Henry Ready, and 56 wounded severely and slightly, including Captain Dacres himself, the first lieutenant, Bartholomew Kent, Master, Robert Scott, two master's mates, and one midshipman.

The third lieutenant of the Constitution, Mr. George Campbell Read, was sent on board the prize, and the Constitution remained by her during the night; but at daylight it was found that she was in danger of sinking. Captain Hull at once began removing the prisoners, and at three o'clock in the afternoon set the Guerrière on fire, and in a quarter of an hour she blew up. He then set sail for Boston, where he arrived on August 30th. "Captain Hull and his officers," writes Captain Dacres in his official letter, "have treated us like brave and generous enemies; the greatest care has been taken that we should not lose the smallest trifle."

The British laid very great stress on the rotten and decayed condition of the Guerrière; mentioning in particular that the mainmast fell solely because of the weight of the falling foremast. But it must be remembered that until the action occurred she was considered a very fine ship. Thus, in Brighton's "Memoir of Admiral Broke," it is declared that Dacres freely expressed the opinion that she could take a ship in half the time the Shannon could. The fall of the main-mast occurred when the fight was practically over; it had no influence whatever on the conflict. It was also asserted that her powder was bad, but on no authority; her first broadside fell short, but so, under similar circumstances, did the first broadside of the United States. None of these causes account for the fact that her shot did not hit. Her opponent was of such superior force—nearly in the proportion of 3 to 2—that success would have been very difficult in any event, and no one can doubt the gallantry and pluck with which the British ship was fought; but the execution was very greatly disproportioned to the force. The gunnery of the Guerrière was very poor, and that of the Constitution excellent; during the few minutes the ships were yard-arm and yard-arm; the latter was not hulled once, while no less than 30 shot took effect on the former's engaged side, [Footnote: Captain Dacres' address to the court-martial.] five sheets of copper beneath the bends. The Guerrière, moreover, was out-manoeuvred; "in wearing several times and exchanging broadsides in such rapid and continual changes of position, her fire was much more harmless than it would have been if she had kept more steady." [Footnote: Lord Howard Douglass, "Treatise on Naval Gunnery" (London, 1851), p. 454.] The Constitution was handled faultlessly; Captain Hull displayed the coolness and skill of a veteran in the way in which he managed, first to avoid being raked, and then to improve the advantage which the precision and rapidity of his fire had gained. "After making every allowance claimed by the enemy, the character of this victory is not essentially altered. Its peculiarities were a fine display of seamanship in the approach, extraordinary efficiency in the attack, and great readiness in repairing damages; all of which denote cool and capable officers, with an expert and trained crew; in a word, a disciplined man-of-war." [Footnote: Cooper, ii. 173.] The disparity of force, 10 to 7, is not enough to account for the disparity of execution, 10 to 2. Of course, something must be allowed for the decayed state of the Englishman's masts, although I really do not think it had any influence on the battle, for he was beaten when the main mast fell; and it must be remembered, on the other hand, that the American crew was absolutely new, while the Guerrière was manned by old hands. So that, while admitting and admiring the gallantry, and, on the whole, the seamanship of Captain Dacres and his crew, and acknowledging that he fought at a great disadvantage, especially in being short-handed, yet all must acknowledge that the combat showed a marked superiority, particularly in gunnery, on the part of the Americans. Had the ships not come foul, Captain Hull would probably not have lost more than three or four men; as it was, he suffered but slightly. That the Guerrière was not so weak as she was represented to be can be gathered from the fact that she mounted two more main-deck guns than the rest of her class; thus carrying on her main-deck 30 long 18-pounders in battery, to oppose to the 30 long 24's, or rather (allowing for the short weight of shot) long 22's, of the Constitution. Characteristically enough, James, though he carefully reckons in the long bow-chasers in the bridle-ports of the Argus and Enterprise, yet refuses to count the two long eighteens mounted through the bridle-ports on the Guerrière's main-deck. Now, as it turned out, these two bow guns were used very effectively, when the ships got foul, and caused more damage and loss than all of the other main-deck guns put together.

[Illustration: This diagram is taken from Commodore Morris' autobiography and the log of the Guerrière: the official accounts apparently consider "larboard" and "starboard" as interchangeable terms.]

Captain Dacres, very much to his credit, allowed the ten Americans on board to go below, so as not to fight against their flag; and in his address to the court-martial mentions, among the reasons for his defeat, "that he was very much weakened by permitting the Americans on board to quit their quarters." Coupling this with the assertion made by James and most other British writers that the Constitution was largely manned by Englishmen, we reach the somewhat remarkable conclusion, that the British ship was defeated because the Americans on board would not fight against their country, and that the American was victorious because the British on board would. However, as I have shown, in reality there were probably not a score of British on board the Constitution.

In this, as well as the two succeeding frigate actions, every one must admit that there was a great superiority in force on the side of the victors, and British historians have insisted that this superiority was so great as to preclude any hopes of a successful resistance. That this was not true, and that the disparity between the combatants was not as great as had been the case in a number of encounters in which English frigates had taken French ones, can be best shown by a few accounts taken from the French historian Troude, who would certainly not exaggerate the difference. Thus on March 1, 1799, the English 38-gun 18-pounder frigate Sybille, captured the French 44-gun 24-pounder frigate Forte, after an action of two hours and ten minutes. [Footnote: "Batailles Navales de la France." O. Troude (Paris, 1868), iv, 171.] In actual weight the shot thrown by one of the main-deck guns of the defeated Forte was over six pounds heavier than the shot thrown by one of the main-deck guns of the victorious Constitution or United States. [Footnote: See Appendix B, for actual weight of French shot.]

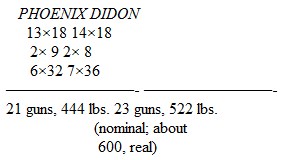

There are later examples than this. But a very few years before the declaration of war by the United States, and in the same struggle that was then still raging, there had been at least two victories gained by English frigates over French foes as superior to themselves as the American 44's were to the British ships they captured. On Aug. 10, 1805, the Phoenix, 36, captured the Didon, 40, after 3 1/2 hours' fighting, the comparative broadside force being: [Footnote: Ibid., lii, 425.]

On March 8, 1808, the San Florenzo, 36, captured the Piedmontaise, 40, the force being exactly what it was in the case of the Phoenix and Didon.[Footnote: Ibid., in, 499.] Comparing the real, not the nominal weight of metal, we find that the Didon and Piedmontaise were proportionately of greater force compared to the Phoenix and San Florenzo, than the Constitution was compared to the Guerrière or Java. The French 18's threw each a shot weighing but about two pounds less than that thrown by an American 24 of 1812, while their 36-pound carronades each threw a shot over 10 pounds heavier than that thrown by one of the Constitution's spar-deck 32's.

That a 24-pounder can not always whip an 18-pounder frigate is shown by the action of the British frigate Eurotas with the French frigate Chlorinde, on Feb. 25, 1814. [Footnote: James, vi, 391.] The first with a crew of 329 men threw 625 pounds of shot at a broadside, the latter carrying 344 men and throwing 463 pounds; yet the result was indecisive. The French lost 90 and the British 60 men. The action showed that heavy metal was not of much use unless used well.

To appreciate rightly the exultation Hull's victory caused in the United States, and the intense annoyance it created in England, it must be remembered that during the past twenty years the Island Power had been at war with almost every state in Europe, at one time or another, and in the course of about two hundred single conflicts between ships of approximately equal force (that is, where the difference was less than one half), waged against French, Spanish, Italian, Turkish, Algerine, Russian, Danish, and Dutch antagonists, her ships had been beaten and captured in but five instances. Then war broke out with America, and in eight months five single-ship actions occurred, in every one of which the British vessel was captured. Even had the victories been due solely to superior force this would have been no mean triumph for the United States.

On October 13, 1812, the American 18-gun ship-sloop Wasp, Captain Jacob Jones, with 137 men aboard, sailed from the Delaware and ran off southeast to get into the track of the West India vessels; on the 16th a heavy gale began to blow, causing the loss of the jib-boom and two men who were on it. The next day the weather moderated somewhat, and at 11.30 P.M., in latitude 37° N., longitude 65° W., several sail were descried. [Footnote: Capt. Jones' official letter, Nov. 24, 1812.] These were part of a convoy of 14 merchant-men which had quitted the bay of Honduras on September 12th, bound for England, [Footnote: James' History, vi, 158.] under the convoy of the British 18-gun brig-sloop Frolic, of 19 guns and 110 men, Captain Thomas Whinyates. They had been dispersed by the gale of the 16th, during which the Frolic's main-yard was carried away and both her top-sails torn to pieces [Footnote: Capt. Whinyates' official letter, Oct. 18, 1812.]; next day she spent in repairing damages, and by dark six of the missing ships had joined her. The day broke almost cloudless on the 18th (Sunday), showing the convoy, ahead and to leeward of the American ship, still some distance off, as Captain Jones had not thought it prudent to close during the night, while he was ignorant of the force of his antagonists. The Wasp now sent down to her top-gallant yards, close reefed her top-sails, and bore down under short fighting canvas; while the Frolic removed her main-yard from the casks, lashed it on deck, and then hauled to the wind under her boom main-sail and close-reefed foretop-sail, hoisting Spanish colors to decoy the stranger under her guns, and permit the convoy to escape. At 11.32 the action began—the two ships running parallel on the starboard tack, not 60 yards apart, the Wasp, firing her port, and the Frolic her starboard, guns. The latter fired very rapidly, delivering three broadsides to the Wasp's two, [Footnote: Cooper, 182.] both crews cheering loudly as the ships wallowed through the water. There was a very heavy sea running, which caused the vessels to pitch and roll heavily. The Americans fired as the engaged side of their ship was going down, aiming at their opponent's hull [Footnote: Miles' Register, in, p. 324.]; while the British delivered their broadsides while on the crests of the seas, the shot going high. The water dashed in clouds of spray over both crews, and the vessels rolled so that the muzzles of the guns went under. [Footnote: Do.] But in spite of the rough weather, the firing was not only spirited but well directed. At 11.36 the Wasp's maintop-mast was shot away and fell, with its yard, across the port fore and foretop-sail braces, rendering the head yards unmanageable; at 11.46 the gaff and mizzentop-gallant mast came down, and by 11.52 every brace and most of the rigging was shot away. [Footnote: Capt. Jones' letter.] It would now have been very difficult to brace any of the yards. But meanwhile the Frolic suffered dreadfully in her hull and lower masts, and had her gaff and head braces shot away.[Footnote: Capt. Whinyates' letter.] The slaughter among her crew was very great, but the survivors kept at their work with the dogged courage of their race. At first the two vessels ran side by side, but the American gradually forged ahead, throwing in her fire from a position in which she herself received little injury; by degrees the vessels got so close that the Americans struck the Frolic's side with their rammers in loading, [Footnote: Capt. Jones' letter.] and the British brig was raked with dreadful effect. The Frolic then fell aboard her antagonist, her jib-boom coming in between the main- and mizzen-rigging of the Wasp and passing over the heads of Captain Jones and Lieutenant Biddle, who were standing near the capstan. This forced the Wasp up in the wind, and she again raked her antagonist, Captain Jones trying to restrain his men from boarding till he could put in another broadside. But they could no longer be held back, and Jack Lang, a New Jersey seaman, leaped on the Frolic's bowsprit. Lieutenant Biddle then mounted on the hammock cloth to board, but his feet got entangled in the rigging, and one of the midshipmen seizing his coat-tails to help himself up, the lieutenant tumbled back on the deck. At the next swell he succeeded in getting on the bowsprit, on which there were already two seamen whom he passed on the forecastle. But there was no one to oppose him; not twenty Englishmen were left unhurt. [Footnote: Capt. Whinyates' letter.] The man at the wheel was still at his post, grim and undaunted, and two or three more were on deck, including Captain Whinyates and Lieutenant Wintle, both so severely wounded that they could not stand without support. [Footnote: James, vi, 161.] There could be no more resistance, and Lieutenant Biddle lowered the flag at 12.15—just 43 minutes after the beginning of the fight. [Footnote: Capt. Jones' letter.] A minute or two afterward both the Frolic's masts went by the board—the foremast about fifteen feet above the deck, the other short off. Of her crew, as already said, not twenty men had escaped unhurt. Every officer was wounded; two of them, the first lieutenant, Charles McKay, and master, John Stephens, soon died. Her total loss was thus over 90 [Footnote: Capt. Whinyates' official letter thus states it, and is, of course, to be taken as authority; the Bermuda account makes it 69, and James only 62;] about 30 of whom were killed outright or died later. The Wasp suffered very severely in her rigging and aloft generally, but only two or three shots struck her hull; five of her men were killed—two in her mizzen-top and one in her maintop-mast rigging—and five wounded, [Footnote: Capt. Jones' letter.] chiefly while aloft.