полная версия

полная версияPagan and Christian Rome

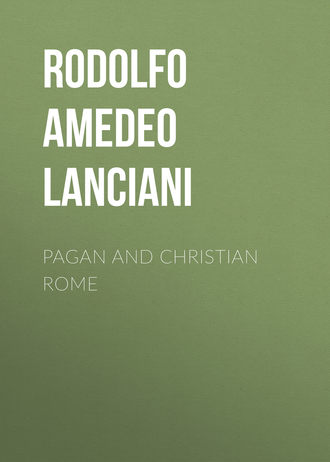

The entrance to the crypt, discovered in 1714 and again in 1865, near the farmhouse of Tor Marancia, at the first milestone of the Via Ardeatina, is hewn out of a perpendicular cliff, which is conspicuous from the high road (the modern Via delle Sette Chiese). The crypt is approached through a vestibule, which was richly decorated with terra-cotta carvings, and, on the frieze, a monumental inscription enclosed by an elaborate frame. No pagan mausolea of the Via Appia or the Via Latina show a greater sense of security or are placed more conspicuously than this early Christian tomb. The frescoes on the ceiling of the vestibule, representing biblical scenes, such as Daniel in the lions' den, the history of Jonah, etc., were exposed to daylight, and through the open door could be seen by the passer. No precaution was taken to conceal these symbolic scenes from profane or hostile eyes. We regret the loss of the inscription above the entrance, which, besides the name of the owner of the crypt, probably contained the lex monumenti, and a formula specifying the religion of those buried within. In this very catacomb, a few steps from the vestibule, an inscription has been found, in which a Marcus Aurelius Restitutus declares that he has built a tomb for himself and his relatives (sibi et suis), provided they were believers in Christ (fidentes in Domino). Another tombstone, discovered in 1864, in the Villa Patrizi, near the catacombs of Nicomedes, states that none might be buried in the tomb to which it was attached except those who belonged to the creed (pertinentes ad religionem) of the founder.

Entrance to the Crypt of the Flavians.

The time soon came when these frank avowals of Christianity were either impossible or extremely hazardous; and although legally a tomb continued to be a locus religiosus, no matter what the creed of the deceased had been, a vague sense of anxiety was felt by the Church, lest even these last refuges should be violated by the mob and its leaders. Hence the extraordinary development which underground cemeteries underwent towards the end of the first and the beginning of the second century. These catacombs were considered by the law to be the property of the citizen who owned the ground above, and who either excavated them at his own cost, or gave the privilege of doing so to the Church. This is the reason why the names of our oldest suburban cemeteries are derived, not from the illustrious saints buried in them, but from the owner of the property under which the catacomb was first excavated. Balbina, Callixtus, Domitilla were never laid to rest in the catacombs which bear their names. Prætextatus, Apronianus, the Jordans, Novella, Pontianus, and Maximus, after whom other cemeteries were named, are all totally unknown persons. When these cemeteries became places of worship and pilgrimage, after the Peace of Constantine, the old names which had sheltered them from the violence of persecutors were abandoned, and replaced by those of local martyrs. Thus the catacomb of Domitilla became that of Nereus and Achilleus; that of Balbina was named for S. Mark; that of Callixtus for SS. Sixtus and Cæcilia; and that of Maximus for S. Felicitas.

One characteristic of Christian epigraphy shows what a comparatively safe place the catacombs were. Inscriptions belonging to them never contain those requests to the passer to respect the tomb, which are so frequent in sepulchral inscriptions from tombs above-ground, and which sometimes, on Christian as well as pagan graves, take the form of an imprecation. An epitaph discovered by Hamilton near Eumenia, Phrygia, contains this rather violent formula: "May the passer who damages my tomb bury all his children at the same time." In another, found near the church of S. Valeria, in Milan, the imprecation runs: "May the wrath of God and of his Christ fall on the one who dares to disturb the peace of our sleep."

The safety of the catacombs was not due to the fact that their existence was known only to the proselytes of Christ. The magistrates possessed a thorough knowledge of their location, number, and extent; and we have evidence of raids and descents by the police on extraordinary occasions, as, for instance, during the persecutions of Valerian and Diocletian. The ordinary entrances to the catacombs, which were known to the police, were sometimes walled up or otherwise concealed, and new secret outlets opened through abandoned pozzolana quarries (arenariæ). Some of these outlets have been discovered, or are to be seen, in the cemeteries of Agnes, Thrason, Callixtus, and Castulus. In May, 1867, while excavating on the southern boundary line of the Cemetery of Callixtus, de Rossi found himself suddenly confronted with sandpits, the galleries of which came in contact with those of the cemetery several times. The passage from one to the other had been most ingeniously disguised by the fossores, as those who dug the catacombs were called.149

The defence of these cemeteries in troubled times must have caused great anxiety to the Church. Tertullian tells how the population of Carthage, excited against the Christians, sought to obtain from Hilarianus, governor of Africa, the destruction of their graves. "Let them have no burial-ground!" (areæ eorum non sint) was the rallying cry of the mob.

The catacombs are unfit for men to live in, or to stay in even for a few days. The tradition that Antonio Bosio spent seventy or eighty consecutive hours in their depths is unfounded. When we hear of Popes, priests, or their followers seeking refuge in catacombs, we must understand that they repaired to the buildings connected with them, such as the lodgings of the keepers, undertakers, and local clergymen. Pope Boniface I., when molested by Symmachus and Eulalius, found shelter in the house connected with the Cemetery of Maximus on the Via Salaria. The crypts themselves were sought as a refuge only in case of extreme emergency. Thus Barbatianus, a priest from Antiochia, concealed himself in the Catacombs of Callixtus to escape the wrath of Galla Placidia.

Many attempts have been made to estimate the extent of our catacombs, the length of their galleries, and the number of tombs which they contain. Michele Stefano de Rossi, brother of the archæologist, gives the following results for the belt of catacombs within three miles of the gates of Servius:150—

(A) Surface of tufa beds, capable of being excavated into catacombs, 67,000,000 square feet.

(B) Surface actually excavated into catacombs, from one to four stories deep, 22,500,000 square feet,—more than a square mile.

(C) Aggregate length of galleries, calculated on the average construction of six different catacombs, 866 kilometres, equal to 587 geographical miles.

The sides of the galleries contain several rows of loculi, sometimes six or eight. Some bodies are buried under the floor, or in the cubiculi which open right and left at short intervals. Assuming these galleries to be capable of containing two bodies per metre, the number of Christians buried in the catacombs, within three miles from the gates of Servius, may be estimated at a minimum of 1,752,000.

The construction of this prodigious labyrinth required the excavation and removal of 96,000,000 cubic feet of solid rock.

With regard to the number of inscriptions, I quote the following passage from Northcote's "Epitaphs," page 3: "Of Christian inscriptions in Rome, during the first six centuries, de Rossi has studied more than fifteen thousand, the immense majority of which were taken from the catacombs; and he tells us there is still an average yearly addition of about five hundred, derived from the same source. This number, vast as it is, is but a poor remnant of what once existed. From the collections made in the eighth and ninth centuries it appears that there were once at least one hundred and seventy ancient Christian inscriptions in Rome, which had an historical or monumental character; written generally in metre, and to be seen at that time in the places which they were intended to illustrate. Of these only twenty-six remain, either whole or in parts. In the Roman topographies of the seventh century, one hundred and forty sepulchres of famous martyrs and confessors are enumerated; we have recovered only twenty inscribed memorials, to assist us in the identification of these. Only nine epitaphs have come to light belonging to the bishops of Rome during the same six centuries; and yet, during that period, there were certainly buried in the suburbs of the city upwards of sixty. Thus, whatever facts we take as the basis of our calculation, it would seem that scarcely a seventh part of the original wealth of the Roman church in memorials of this kind has survived the wreck of ages; and de Rossi gives it as his conviction that there were once more than one hundred thousand of them."

When the catacombs began to be better known to the general public, and were visited by crowds of the devout or curious, they became one of the marvels of Rome. Travellers who so admired the syringes or crypts of the kings of Thebes, calling them τα θαυματα (the wonders), could not help being struck with awe at the great work accomplished by our Christian community in less than three centuries. An inscription found by Deville at Thebes, in one of the royal crypts, and published in the "Archives des missions scientifiques," 1866, vol. ii. p. 484, thus refers to the parallel wonders of Roman and Egyptian catacombs: "Antonius Theodorus, intendant of Egypt and Phœnicia, who has spent many years in the Queen-city of Rome, has seen the wonders (τα θαυματα) both there and here." The allusion to the catacombs in comparison with the syringes is evident. The inscription dates from the second half of the fourth century.

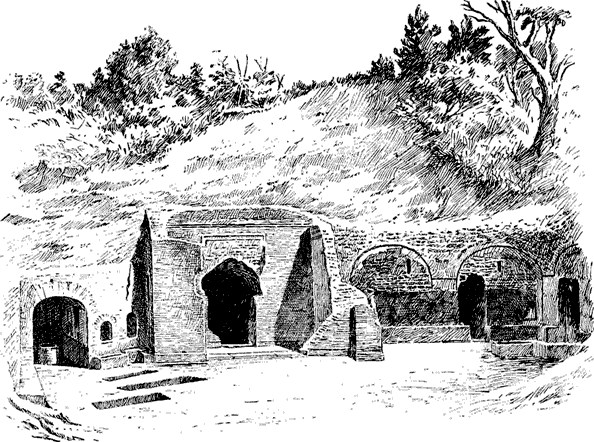

To the edict of Milan, and to the peace which it gave to the Church, we must attribute the origin of the decadence of underground cemeteries. Burial in open-air cemeteries having become secure once more, there was no reason why the faithful should give preference to the unhealthy and overcrowded crypts below. The example of desertion was set by the Popes themselves. Melchiades (311-314), who was the first to occupy the Lateran palace after the victory of the Church, was the last Pope buried near his predecessors in cœmeteris Callisti in cripta. Sylvester, his successor, was buried in a chapel built expressly, above the crypt of Priscilla, Mark above the crypts of Balbina, Julius above those of Calepodius, and so on. Still, the desire of securing a grave in proximity to the shrine of a martyr was so intense that the use of the catacombs lasted for a century longer, although in diminishing proportions. When a gallery is discovered which contains more graves than usual, and has been excavated even in the narrow ledges of rock which separated the original loculi, or else at the corners of the crossings, which were usually left untouched, as protection against the caving-in of the earth, we may be sure we are approaching a martyr's altar-tomb. Sometimes the paintings which decorate a martyr's cubiculum have been disfigured and their inscriptions effaced by an overzealous devotee. The accompanying cut shows the damage inflicted on a picture of the Good Shepherd in the cubiculum of S. Januarius, in the Catacombs of Prætextatus, by an unscrupulous disciple who wished to be buried as near as possible to his patron-saint.

Cubiculum of Januarius.

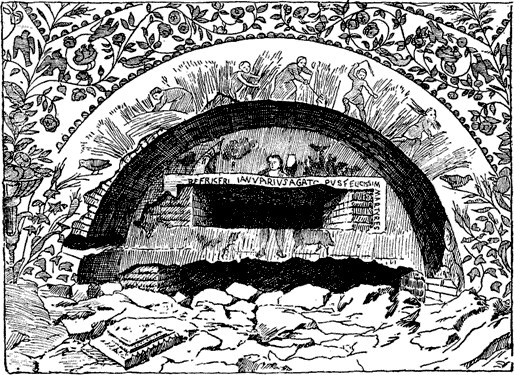

By the end of the fourth century burials in catacombs became rare, and still more between 400 and 410. They were apparently given up altogether after 410. The development of open-air cemeteries increased in proportion, those of S. Lorenzo and S. Paolo fuori le Mura being among the most popular. In 1863, when the entrance-gate to the modern Camposanto adjoining S. Lorenzo was built, fifty tombs, mostly unopened, were found in a space ninety feet long by forty feet wide. Since that time five hundred tombstones have been gathered in the neighborhood of that favorite church. As regards S. Paul's cemetery, more than one thousand inscriptions, whole or in fragments, were found in rebuilding the basilica and its portico, after the fire of 1823;151 two hundred in the excavations of S. Valentine's basilica, outside the Porta del Popolo. These last excavations are the only ones illustrating a Christian cemetery which are left visible; but their importance is limited. The cemeteries of Arles and Pola, alluded to by Dante, have disappeared; and so has the magnificent one of the officers and men employed in the Roman arsenal at Concordia Sagittaria, which was discovered in 1873, near Portogruaro, by Perulli and Bartolini. This cemetery, which contains, in the section already explored, nearly two hundred sarcophagi, cut in limestone, in the shape of Petrarch's coffin, at Arquà, or Antenor's at Padua, was wrecked by Attila in 452, and buried soon after by an inundation of the river Tagliamento, which spread masses of mud and sand over the district, and raised its level five feet. The accompanying plate is from a photograph taken at the time of the discovery.

I have just stated that burial in catacombs seems to have been abandoned in 410, because no inscription of a later date has yet been found. The reader will easily perceive the reason for the abandonment. On August 10, 410, Rome was stormed by Alaric, and the suburbs devastated. This fatal year marks the end of a great and glorious era in Christian epigraphy, and in the history of catacombs the end of the work of the fossores. More fatal still was the barbaric invasion of 457. The actual destruction began in 537, during the siege of Rome by Vitiges. The biographer of Pope Silverius expressly says: "Churches and tombs of martyrs have been destroyed by the Goths" (ecclesiæ et corpora sanctorum martyrum exterminata sunt a Gothis). It is difficult to explain why the Goths, confessed and even bigoted Christians (Arians) as they were, and full of respect for the basilicas of S. Peter and S. Paul, as Procopius declares, should have ransacked the catacombs, violated the tombs of martyrs, and broken their historical inscriptions. Perhaps it was because none of the barbarians could read Latin or Greek epitaphs, and make the distinction between pagan and Christian cemeteries; or perhaps they were moved by the desire of finding hidden treasures, or securing relics of saints. Whatever may have been the reason of their behavior, we must remember that two encampments, at least, of the Goths were just over catacombs and around their entrances; one on the Via Salaria, over those of Thrason; the other on the Via Labicana, above those of Peter and Marcellinus. The barbarians could not resist the temptation of exploring those subterranean wonders; indeed they were obliged to do so by the most elementary rules of precaution in order to insure the safety of their intrenchments against surprises. Here I have to record a remarkable coincidence. In each of these two catacombs the following memorial tablet has been seen or found, written in distichs by Pope Virgilius:—

CHRISTIAN MILITARY CEMETERY OF CONCORDIA SAGITTARIA

"When the Goths pitched their camps under the walls of Rome, they declared an impious war against the Saints:

"And destroyed in their sacrilegious attack the tombs dedicated to the memory of martyrs:

"Whose epitaphs, composed by Pope Damasus, have been destroyed.

"Pope Virgilius, having witnessed the destruction, has repaired the tombs, the inscriptions, and the underground sanctuaries after the retreat of the Goths."

The repairs must have been made in haste, between March, 537, the date of the flight of Vitiges, and the following November, the date of the journey of Virgilius to Constantinople, from which he never returned. Traces of this Pope's restorations have been found in other catacombs. In those of Callixtus the fragments of a tablet, dedicated by Damasus to S. Eusebius, have been found, dispersed over a large area, and also a copy set up by Virgilius in the place of the original. In those of Hippolytus, on the Via Tiburtina, an inscription was discovered in 1881, which stated that the "sacred caverns" had been restored præsule Virgilio. The example of Virgilius and his successors in the See of Rome was followed by private individuals. The tomb of Crysanthus and Daria on the Via Salaria was restored, after the retreat of the barbarians, pauperis ex censu, that is to say, with the modest means of a devotee.

Nibby has attributed the origin of cemeteries within the walls to the invasion of Vitiges, burial within the city limits having been strictly forbidden by the laws of Rome. But the law seems to have been practically disregarded even before the Gothic wars. Christians were buried in the Prætorian camp, and in the gardens of Mæcenas, during the reign of Theodoric (493-526). I have mentioned this particular because it marks another step towards the abandonment of suburban cemeteries. The country around Rome having become insecure and deserted, it was deemed necessary to place within the protection of the city walls the bodies of martyrs who had been buried at a great distance from the gates. The first translation took place in 648: the second in 682, when the bodies of Primus and Felicianus were removed from Nomentum, and those of Viatrix, Faustinus and Simplicius from the Lucus Arvalium (Monte delle Piche, by la Magliana). The last blow to the catacombs was given by Paschal I. (817-824). Contemporary documents mention innumerable transferences of bodies. The mosaic legend of the apse of S. Prassede says that Pope Paschal buried the bodies of many saints within its walls.152

The official catalogue of the remains removed on July 20, 817, which was compiled by the Pope's notary and engraved on marble, has come down to us. It speaks of the translation of twenty-three hundred bodies, most of which were buried under the chapel of S. Zeno, which Paschal I. had built as a memorial to his mother, Theodora Episcopa. The legend in the apse of S. Cæcilia speaks, likewise, of the transference to her church of bodies "which had formerly reposed in crypts" (quæ primum in cryptis pausabant): among them those of Cæcilia herself, Valerianus, Tiburtius, and Maximus. The finding and removal of Cæcilia's remains from the Catacombs of Callixtus is one of the most graceful episodes in the life of Paschal I. He describes it at length in a letter addressed to the people of Rome.

After many unsuccessful attempts to discover the coffin of the saint, he had come to the conclusion that it must have been stolen by the Lombards, when they were besieging the city in 755. S. Cæcilia, however, told him in a vision where her grave was; and hurrying to the catacombs of the Appian Way he at last discovered her crypt and coffin, together with those of fourteen Popes, from Zephyrinus to Melchiades. It is only fair to say that the discoveries made in this very crypt, between 1850 and 1853, confirm the account of Paschal in its minutest details.

The first half of the ninth century thus marks the final abandonment of the catacombs, and the cessation of divine worship in their historical crypts. In later times we find little or no mention of them in Church annals. When we read of Nicholas I. (858-867) and of Paschal II. (1099-1118) visiting the cemeteries, we must believe that their visits were to the basilicas erected over the catacombs, and to their special crypts, not to the catacombs themselves. In the chronicle of the monastery of S. Michael ad Mosam we read of a pilgrim of the eleventh century who obtained relics of saints "from the keeper of a certain cemetery, in which lamps are always burning." He refers to the basilica of S. Valentine and the small hypogæum attached to it (discovered in 1887), not to catacombs in the true sense of the word. The very last account referring directly to them dates from the time of Pope Nicholas I. (858-867) who is said to have restored the crypt of Mark on the Via Ardeatina, and of Felix, Abdon, and Sennen on the Via Portuensis. At this time also the visits of pilgrims, to whose itineraries, or guidebooks, we are indebted for so much knowledge of the topography of suburban cemeteries, come to an end. The best itineraries are those of Einsiedeln, Salzburg, Wurzburg, and William of Malmesbury; and the list of the oils from the lamps burning before the tombs of martyrs, which were collected by John, abbot of Monza, at the request of queen Theodolinda. The pilgrims left many records of their visits scratched on the walls of the sanctuaries; and to these graffiti also we are indebted for much information, since they contain formulas of devotion addressed to the saint of the place. They are very interesting in their simplicity of thought and diction, as are generally the memoirs of early pilgrims and pilgrimages. I shall mention one, discovered not many years ago in the cemetery of Mustiola at Chiusi. It is a plain tombstone, inscribed with the words:—

HIC · POSITUS · EST · PEREGRINUS · CICONIAS · CUIUS ·NOMEN · DEUS · SCIT"Here is buried a pilgrim from Thrace, whose name is known only to God." The tale is simple and touching. A pilgrim on his way to Rome, or back to his country, was overtaken by death at Chiusi, before he could make himself known to those who had come to his help. They could only suppose he had come from Thrace, the country of the Cicones, possibly from the language he spoke, or from the costume he wore.

On May 31, 1578, a workman, while digging a sandpit in the vineyard of Bartolomeo Sanchez at the second milestone of the Via Salaria, came upon a Christian cemetery containing frescoes, sarcophagi, and inscriptions. This unexpected discovery created a great sensation,153 and the report was circulated that an underground city had been found. The leading men of the age hastened to the spot; among them Baronius, who speaks of these wondrous crypts three or four times in his annals.154 It seems that the network of galleries, crossing one another at various angles, the skylights, the wells, the symmetry of the cubiculi and arcosolia, the number of loculi with which the sides of the galleries were honeycombed, affected the imagination of visitors even more than the pictures, the sarcophagi, and the epitaphs. The subjects of the frescoes were so varied as to contain almost the whole cycle of early Christian symbolism. There were the Good Shepherd and the Praying Soul, Noah and the ark, Daniel and the lions, Moses striking the rock, the story of Jonah, the sacrifice of Isaac, the three men in the fiery furnace, the resurrection of Lazarus, etc. The bas-reliefs of the marble coffins represented Christian love-feasts and pastoral scenes. The epitaphs contained simply names, except one, which was raised by a girl "to her sweet nurse Paulina, who dwells in Christ among the blessed." These pious memorials of the primitive church led the learned visitors to investigate their meaning and value, as well as the history and name of those mysterious labyrinths. The origin of Christian archæology, therefore, really dates from May 1, 1578. Antonio Bosio, the Columbus of subterranean Rome, was but three years old at that time, but he seems to have developed his marvellous instinct on the strength of what he saw in the Vigna Sanchez in his boyhood. The crypts, however, had but a short life: the quarry-men damaged and robbed them to such an extent that, when Bosio began his career in 1593, every trace of them had disappeared. They have never been found since. We can only point out to the lover of these studies the site of the Vigna Sanchez. It is marked by a monumental gate, on the right side of the Via Salaria, crowned by the well-known coat-of-arms of the della Rovere family, to whom the property was sold towards the end of the sixteenth century. The gate is a little more than a mile from the Porta Salaria.

From that time to the first quarter of the present century, we have to tell the same long tale of destruction. And who were responsible for this wholesale pillage? The very men—Aringhi, Boldetti, Marangoni, Bottari—who devoted their lives, energies and talents to the study of the catacombs, and to whom we are indebted for many standard works on Christian archæology. Such was the spirit of the age. Whether an historical inscription came out of one cemetery or another did not matter to them; the topographical importance of discoveries was not appreciated. Written or engraved memorials were sought, not for the sake of the history of the place to which they belonged, but to ornament houses, museums, villas, churches and monasteries. In 1863, de Rossi found a portion of the Cemetery of Callixtus, near the tombs of the Popes, in incredible confusion and disorder: loculi ransacked, their contents stolen, their inscriptions broken and scattered far and wide, and the bones themselves taken out of their graves. The perpetrators of the outrage had taken care to leave their names written in charcoal or with the smoke of tallow candles; they were men employed by Boldetti in his explorations of the catacombs, between 1713 and 1717. Some of the tombstones were removed by him to S. Maria in Trastevere, and inserted in the floor of the nave. Benedict XIV. took away the best, and placed them in the Vatican Library. They have now migrated again to the Museo Epigrafico of the Lateran Palace. Those left in the floor of S. Maria in Trastevere were removed to the vestibule of the church in 1865.