полная версия

полная версияPagan and Christian Rome

These various accounts are no doubt written under the excitement of the moment, and by men naturally inclined to exaggeration; still, they all agree in the main details of the discovery,—in the date, the place of discovery, and the description of the corpse. Who was, then, the girl for the preservation of whose remains so much care had been taken?

Pomponio Leto, the leading archæologist of the age, expressed the opinion that she might have been either Tulliola, daughter of Cicero, or Priscilla, wife of Abascantus, whose tomb on the Appian Way is described by Statius (Sylv. V. i. 22). Either supposition is wrong. The first is invalidated by the fact that the body was of a young and tender girl, while Tulliola is known to have died in childbirth at the age of thirty-two. Moreover, there is no document to prove that Cicero had a family vault at the sixth milestone of the Appian Way. The tomb of Priscilla, wife of Abascantus, a favorite freedman of Domitian, is placed by Statius near the bridge of the Almo (Fiume Almone, Acquataccio) four and a half miles nearer the gate; where, in front of the Chapel of Domine quo vadis, it has been found and twice excavated: the first time in 1773 by Amaduzzi; the second in 1887, under my supervision. The only clew worth following is that given in Pehem's letter of April 15, now in the Munich library; but even this leads to no result. The inscription, which was said to mention the name and age of the girl, is perfectly genuine, and duly registered in the "Corpus Inscriptionum," No. 20,634. It is as follows:—

D · MIVLIA · L · L · PRISCAVIX · ANN · XXVI · M · I · D · IQ · CLODIVS · HILARVSVIX · ANN · XXXXVINIHIL · VNQVAM · PECCAVITNISI · QVOD · MORTVA · EST"To the infernal gods. [Here lie] Julia Prisca, freedwoman of Lucius Julius, who lived twenty-six years one month, one day; [and also] Q. Clodius Hilarus, who lived forty-six years. She never did any wrong except to die." Pehem, Malaguy, Fantaguzzi, Waelscapple and all the rest of them, assert unanimously that the inscription was found with the body on April 16, 1485, and they are all mistaken. It had been seen and copied, at least twenty-two years before, by Felix Felicianus of Verona, and is to be found in the MSS. collection of ancient epitaphs, which he dedicated to Andrea Mantegna in 1463. The number of spurious inscriptions concocted for the occasion is truly remarkable. Georges of Spalato (1484-1545) gives the following version of this one in his MSS. diary, now in Weimar: "Here lies my only daughter Tulliola, who has committed no offence, except to die. Marcus Tullius Cicero, her unhappy father, has raised this memorial."

The poor girl, whose name and condition in life will never be known, and whose body for twelve centuries had so wonderfully escaped destruction, was most abominably treated by her discoverers in 1485. There are two versions as to her ultimate fate. According to one, Pope Innocent VIII., to stop the excitement and the superstitions of the citizens, caused the conservatori to remove the body at night outside the Porta Salaria, and bury it secretly at the foot of the city walls. According to the second it was thrown into the Tiber. One is just about as probable as the other.

How differently we treat these discoveries in our days! In the early morning of May 12, 1889, I was called to witness the opening of a marble coffin which had been discovered two days before, under the foundations of the new Halls of Justice, on the right bank of the Tiber, near Hadrian's Mausoleum. As a rule, the ceremony of cutting the brass clamps which fasten the lids of urns and sarcophagi is performed in one of our archæological repositories, where the contents can be quietly and carefully examined, away from an excited and sometimes dangerous crowd. In the present case this plan was found impracticable, because the coffin was ascertained to be filled with water which had, in the course of centuries, filtered in, drop by drop, through the interstices of the lid. The removal to the Capitol was therefore abandoned, not only on account of the excessive weight of the coffin, but also because the shaking of the water would have damaged and disordered the skeleton and the objects which, perchance, were buried inside.

The marble sarcophagus was embedded in a stratum of blue clay, at a depth of twenty-five feet below the level of the city, that is, only four or five feet above the level of the Tiber, which runs close by. It was inscribed simply with the name CREPEREIA TRYPHAENA, and decorated with bas-reliefs representing the scene of her death. No sooner had the seals been broken, and the lid put aside, than my assistants, myself, and the whole crowd of workmen from the Halls of Justice, were almost horrified at the sight before us. Gazing at the skeleton through the veil of the clear water, we saw the skull covered, as it were, with long masses of brown hair, which were floating in the liquid crystal. The comments made by the simple and excited crowd by which we were surrounded were almost as interesting as the discovery itself. The news concerning the prodigious hair spread like wild-fire among the populace of the district; and so the exhumation of Crepereia Tryphæna was accomplished with unexpected solemnity, and its remembrance will last for many years in the popular traditions of the new quarter of the Prati di Castello. The mystery of the hair is easily explained. Together with the spring-water, germs or seeds of an aquatic plant had entered the sarcophagus, settled on the convex surface of the skull, and developed into long glossy threads of a dark shade.

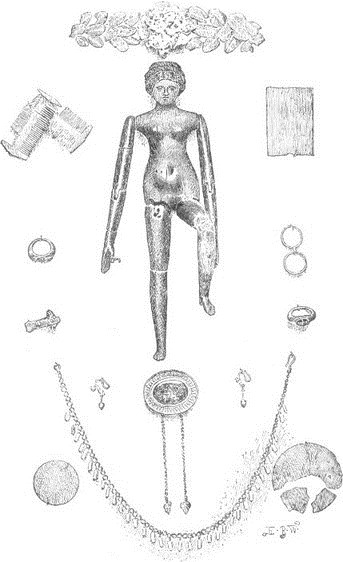

OBJECTS FOUND IN THE GRAVE OF CREPEREIA TRYPHÆNA

The skull was inclined slightly towards the left shoulder and towards an exquisite little doll, carved of oak, which was lying on the scapula, or shoulder-blade. On each side of the head were gold earrings with pearl drops. Mingled with the vertebræ of the neck and back were a gold necklace, woven as a chain, with thirty-seven pendants of green jasper, and a brooch with an amethyst intaglio of Greek workmanship, representing the fight of a griffin and a deer. Where the left hand had been lying, we found four rings of solid gold. One is an engagement-ring, with an engraving in red jasper representing two hands clasped together. The second has the name PHILETVS engraved on the stone; the third and fourth are plain gold bands. Proceeding further with our exploration, we discovered, close to the right hip, a box containing toilet articles. The box was made of thin pieces of hard wood, inlaid alla Certosina, with lines, squares, circles, triangles, and diamonds, of bone, ivory, and wood of various kinds and colors. The box, however, had been completely disjointed by the action of the water. Inside there were two fine combs in excellent preservation, with the teeth larger on one side than on the other: a small mirror of polished steel, a silver box for cosmetics, an amber hairpin, an oblong piece of soft leather, and a few fragments of a sponge.140 The most impressive discovery was made after the removal of the water, and the drying of the coffin. The woman had been buried in a shroud of fine white linen, pieces of which were still encrusted and cemented against the bottom and sides of the case, and she had been laid with a wreath of myrtle fastened with a silver clasp about the forehead. The preservation of the leaves is truly remarkable.

Who was this woman, whose sudden and unexpected reappearance among us on the twelfth of May, 1889, created such a sensation? When did she live? At what age did she die? What caused her death? What was her condition in life? Was she beautiful? Why was she buried with her doll? The careful examination of the tomb and its contents enable us to answer all these questions satisfactorily.

Crepereia Tryphæna lived at the beginning of the third century after Christ, during the reigns of Septimius Severus and Caracalla, as is shown by the form of the letters and the style of the bas-reliefs engraved on the sarcophagus. She was not noble by birth; her Greek surname Tryphæna shows that she belonged to a family of freedmen, former servants of the noble family of the Creperei. We know nothing about her features, except that she had a strong and fine set of teeth. Her figure, however, seems to have been rather defective, on account of a deformity in the ribs, probably caused by scrofula. Scrofula, in fact, seems to have been the cause of her death. In spite of this deformity, however, there is no doubt that she was betrothed to the young man Philetus, whose name is engraved on the stone of the second ring, and that the two happy lovers had exchanged the oath of fidelity and mutual devotion for life, which is expressed by the symbol of the clasped hands. The story of her sad death, and of the sudden grief which overtook her family on the eve of a joyful wedding, is plainly told by the presence in the coffin of the doll and the myrtle wreath, which is a corona nuptialis. I believe, in fact, that the girl was buried in her full bridal costume, and then covered with the linen shroud, because there are fragments of clothes of various textures and qualities mixed with those of the white linen.

And now let us turn our attention to the doll. This exquisite pupa, a work of art in itself, is of oak, to which the combined action of time and water has given the hardness of metal. It is modelled in perfect imitation of a woman's form, and ranks amongst the finest of its kind yet found in Roman excavations. The hands and feet are carved with the utmost skill. The arrangement of the hair is characteristic of the age of the Antonines, and differs but little from the coiffure of Faustina the elder. The doll was probably dressed, because in the thumb of her right hand are inserted two gold keyrings like those carried by housewives. This charming little figure, the joints of which at the hips, knees, shoulders, and elbows are still in good order, is nearly a foot high. Dolls and playthings are not peculiar to children's tombs. It was customary for young ladies to offer their dolls to Venus or Diana on their wedding-day. But this was not the end reserved for Crepereia's doll. She was doomed to share the sad fate of her young mistress, and to be placed with her corpse, before the marriage ceremony could be performed.

CHAPTER VII.

CHRISTIAN CEMETERIES. 141

Sanctity of tombs guaranteed to all creeds alike.—The Christians' preference for underground cemeteries not due to fear at first.—Origin and cause of the first persecutions.—The attitude of Trajan towards the Christians, and its results.—The persecution of Diocletian.—The history of the early Christians illustrated by their graves.—The tombs of the first century.—The catacombs.—How they were named.—The security they offered against attack.—Their enormous extent.—Their gradual abandonment in the fourth century.—Open-air cemeteries developed in proportion.—The Goths in Rome.—Their pillage of the catacombs.—Thereafter burial within the city walls became common.—The translation of the bodies of martyrs.—Pilgrims and their itineraries.—The catacombs neglected from the ninth to the sixteenth century.—Their discovery in 1578.—Their wanton treatment by scholars of that time.—Artistic treasures found in them.—The catacombs of Generosa.—The story of Simplicius, Faustina and Viatrix.—The cemetery of Domitilla.—The Christian Flavii buried there.—The basilica of Nereus, Achilleus and Petronilla.—The tomb of Ampliatus.—Was this S. Paul's friend?—The cemetery "ad catacumbas."—The translation of the bodies of SS. Peter and Paul.—The types of the Saviour in early art.—The cemetery of Cyriaca.—Discoveries made there.—Inscriptions and works of art.—The cemetery "ad duas Lauros."—Frescoes in it.—The symbolic supper.—The discoveries of Monsignor Wilpert.—The Academy of Pomponio Leto.

The Roman law which established the inviolability of tombs did not make exceptions either of persons or creeds. Whether the deceased had been pious or impious, a worshipper of Roman or foreign gods, or a follower of Eastern or barbaric religions, his burial-place was considered by law a locus religiosus, as inviolable as a temple. In this respect there was no distinction between Christians, pagans, and Jews; all enjoyed the same privileges, and were subject to the same rules. It is not easy to decide whether this condition of things was an advantage to the faithful. It was certainly advantageous to the Church that her cemeteries should be considered sacred by the law, and that the State itself should enforce and guarantee the observance of the rules (lex monumenti) made by the deceased in connection with his interment, and tomb; but as the police of cemeteries, and the enforcement of the leges monumentorum, was intrusted to the college of high priests, who were stern champions of paganism, the church was liable to be embarrassed in many ways. When, for instance, a body had to be transferred from its temporary repository to the tomb, it was necessary to obtain the consent of the pontifices; which was also required in case of subsequent removals, and even of simple repairs to the building. Roman epitaphs constantly refer to this authority of the pontiffs, and one of them, discovered by Ficoroni in July, 1730, near the Porta Metronia, contains the correspondence exchanged on the subject between the two parties. The petitioner, Arrius Alphius, a favorite freedman of the mother of Antoninus Pius, writes to the high priests: "Having lost at the same time wife and son, I buried them temporarily in a terra-cotta coffin. I have since purchased a burial lot on the left side of the Via Flaminia, between the second and the third milestones, and near the mausoleum of Silius Orcilus, and furnished it with marble sarcophagi. I beg permission of you, my Lords, to transfer the said bodies to the new family vault, so that when my hour shall come, I may be laid to rest beside the dear ones." The answer was: "Granted (fieri placet). Signed by me, Juventius Celsus, vice-president [of the college of pontiffs], on the 3d day of November [a. d. 155]."

The greatest difficulty with which the Christians had to deal was the obligation to perform expiatory sacrifices in given circumstances; as, for instance, when a corpse was removed from one place to another, or when a coffin, damaged by any accidental cause, such as lightning, inundation, fire, earthquake, or violence, had to be opened and the bones exposed to view. But these were exceptional cases; and there is no doubt that the magistrates of Rome were naturally lenient and forbearing in religious matters, except in time of persecution. The partiality shown by early Christians for underground cemeteries is due to two causes: the influence which Eastern customs and the example of the burial of Christ must necessarily have exercised on them, and the security and freedom which they enjoyed in the darkness and solitude of their crypts. Catacombs, however, could not be excavated everywhere, the presence of veins or beds of soft volcanic stone being a condition sine qua non of their existence. Cities and villages built on alluvial or marshy soil, or on hills of limestone and lava, were obliged to resort to open-air cemeteries. In Rome itself these were not uncommon. Certainly there was no reason why Christians should object to the authority of the pontiffs in hygienic and civic matters. This authority was so deeply rooted and respected, that the emperor Constans (346-350), although a stanch Christian and anxious to abolish idolatry, left the pontiffs full jurisdiction over Christian and pagan cemeteries, by a constitution issued in 349.142

From apostolic times to the persecution of Domitian, the faithful were buried, separately or collectively, in private tombs which did not have the character of a Church institution. These early tombs, whether above or below ground, display a sense of perfect security, and an absence of all fear or solicitude. This feeling arose from two facts: the small extent of the cemeteries, which secured to them the rights of private property, and the protection and freedom which the Jewish colony in Rome enjoyed from time immemorial. The Romans of the first century, populace as well as government officials, made no distinction between the proselytes of the Old Testament and those of the New.

Julius Cæsar and Augustus treated the Jews with kindness, and when S. Paul arrived in Rome the colony was living in peace and prosperity, practising religion openly in its Transtiberine synagogues.143 The same state of things prevailed throughout the peninsula. Thus the rabbi or archon of the synagogue at Pompeii called the Synagoga Libertinorum (the existence of which was discovered in September, 1764), could take, in virtue of his office, an active part in city politics and petty municipal quarrels, and in his official capacity could sign a document recommending the election of a candidate for political honors, as is shown by one of the Pompeian inscriptions:—

Cuspium Pansam æd[ilem fieri rogat] Fabius EuporPrinceps Libertinorum.144The persecution which took place under Claudius was really the first connected with the preaching of the gospel. According to Suetonius (Claud. 25) the Jews themselves were the cause of it, having suddenly become uneasy, troublesome, and offensive, impulsore Chresto, that is to say, on account of Christ's doctrine, which was beginning to be preached in their synagogues. The expression used by Suetonius shows how very little was known at the time about the new religion. Although Christ's name was not unknown to him, he speaks of this outbreak under Claudius as having been stirred up personally by a certain Chrestus, as though he were a living member of the Jewish colony. At that early stage the converts to the gospel were identified by the Romans with the Jews, not by mistake or error of judgment, but because they were legally and actually Jews, or rather one Jewish sect which was carrying on a dogmatic war against the others, on a point which had no interest whatever in the eyes of the Romans,—that is, the advent of the Messiah. This statement is corroborated by many passages in the Acts, such as xviii. 15; xxiii. 29; xxv. 9; xxvi. 28, 32; xxviii. 31. Claudius Lysias writes to the governor of Judæa that Paul was accused by his fellow-citizens, not of crimes deserving punishment, but on some controversial point concerning their law. In Rome itself the apostle could preach the gospel with freedom, even when in custody, or under police supervision.145 And as it was lawful for a Roman citizen to embrace the Jewish persuasion, and give up the religion of his fathers, he was equally free to embrace the Evangelic faith, which was considered by the pagans a Jewish sect, not a new belief.

The pagans despised them both, and mixed themselves up with their affairs only from a fiscal point of view, because the Jews were subject to a tax of two drachms per head, and the treasury officials were obliged to keep themselves acquainted with the statistics of the colony.

This state of things did not last very long, it being of vital importance for the Jews to separate their cause from that of the new-comers. The responsibility for the persecutions which took place in the first century must be attributed to them, not to the Romans, whose tolerance in religious matters had become almost a state rule. The first attempt, made under Claudius, was not a success: it ended, in fact, with the banishment from the capital of every Jew, no matter whether he believed in the Old or the New Testament. Judæos, impulsore Chresto assidue tumultuantes, Claudius Romæ expulit (Suetonius: Claud. 25). It was, however, a passing cloud. As soon as they were allowed to come back to their Transtiberine haunts, the Jews set to work again, exciting the feelings of the populace, and denouncing the Christians as conspiring against the State and the gods, under the protection of the law which guaranteed to the Jews the free exercise of their religion. The populace, impressed by the conquests made by the gospel among all classes of citizens, was only too ready to believe the calumny. The Church, repudiated by her mother the Synagogue, could no longer share the privileges of the Jewish community. As for the State, it became a necessity either to recognize Christianity as a new legal religion, or to proscribe and condemn it. The great fire, which destroyed half of Rome under Nero, and which was purposely attributed to the Christians, brought the situation to a crisis. The first persecution began. Had the magistrate who conducted the inquiry been able to prove the indictment of arson, perhaps the storm would have been short, and confined to Rome; but as the Christians could easily exculpate themselves, the trial was changed from a criminal into a politico-religious one. The Christians were convicted not so much of arson (non tam crimine incendii) as of a hatred of mankind (odio generis humani); a formula which includes anarchism, atheism, and high treason. This monstrous accusation once admitted, the persecution could not be limited to Rome; it necessarily became general, and more violent in one place or another, according to the impulse of the magistrate who investigated this entirely unprecedented case.

Was the hope of a legal existence lost forever to the Church? After Nero's death, and the condemnation of his acts and memory, the Christians enjoyed thirty years of peace. Domitian broke it, first, by claiming with unprecedented severity the tribute from the Jews and those "living a Jewish life;"146 secondly, by putting the "atheists," that is, the Christians, to the alternative of giving up their faith or their life. These measures were abolished shortly after by Nerva, who sanctioned the rule that in future no one should be brought to justice under the plea of impiety or Judaism. The answer given by Trajan to Pliny the younger, when governor of Bithynia, is famous in the annals of persecutions. To the inquiries made by the governor, as to the best way of dealing with those "adoring Christ for their God," Trajan replied, that the magistrate should not molest them at his own initiative; but if others should bring them to justice, and convict them of impiety and atheism, they deserved punishment.147 These words contain the solemn recognition of the illegality of Christian worship; they make persecution a rule of state. The faithful were doomed to have no respite for the next two centuries, except what they could obtain at intervals from the personal kindness and tolerance of emperors and magistrates. Those of the Jewish religion continued to enjoy protection and privileges, but Christianity was either persecuted or tolerated, as it happened; so that, even under emperors who abhorred severity and bloodshed, the faithful were at the mercy of the first vagrant who chanced to accuse them of impiety.

Strange to say, more clemency was shown towards them by emperors whom we are accustomed to call tyrants, than by those who are considered models of virtue. The author of the "Philosophumena" (book ix., ch. 11) says that Commodus granted to Pope Victor the liberation of the Christians who had been condemned to the mines of Sardinia by Marcus Aurelius. Thus that profligate emperor was really more merciful to the Church than the philosophic author of the "Meditations," who, in the year 174, had witnessed the miracle of the Thundering Legion. The reason is evident. The wise rulers foresaw the destructive effect of the new doctrines on pagan society, and indirectly on the empire itself; whereas those who were given over to dissipation were indifferent to the danger; "after them, the deluge!"

At the beginning of the third century, under the rule of Caracalla and Elagabalus, the Church enjoyed nearly thirty years of peace, interrupted only by the short persecution of Maximus, and by occasional outbreaks of popular hostility here and there.148

In 249 the "days of terror" returned, and continued fiercer than ever under the rules of Decius, Gallus, and Valerianus. The last persecution, that of Diocletian and his colleagues, was the longest and most cruel of all. For the space of ten years not a day of mercy shone over the ecclesia fidelium. The historian Eusebius, an eye-witness, says that when the persecutors became tired of bloodshed, they contrived a new form of cruelty. They put out the right eyes of the confessors, cut the tendon of their left legs, and then sent them to the mines, lame, half blind, half starved, and flogged nearly to death. In book VIII., chapter 12, the historian says that the number of sufferers was so great that no account could be kept of them in the archives of the Church. The memory of this decade of horrors has never died out in Rome. We have still a local tradition, not altogether unfounded, of ten thousand Christians who were condemned to quarry materials for Diocletian's Baths, and who were put to death after the dedication of the building.