полная версия

полная версияPagan and Christian Rome

The fate of the monument has been truly remarkable. I believe there is no other in the necropolis of the Via Salaria which has undergone so many changes in the course of centuries. The first took place in the reign of Trajan, when the monument was buried under a prodigious mass of earth, together with a large section of an adjoining cemetery. In fact, columbaria dating from the time of Hadrian have been found built against the beautiful inscription of Lucilia Polla; and the inscription itself was disfigured by a coating of red paint, to make it harmonize with the color of the three other walls of the crypt. The whole tract between the Salaria and the Pinciana was raised in the same manner twenty-five feet; and contains, therefore, two layers of tombs,—the lower belonging to the republican or early imperial epoch, the upper to the time of Hadrian and later.

Where did this enormous mass of earth come from?

A clew to the answer is given on page 87 of my "Ancient Rome," where, in describing the construction of Trajan's forum, and the column which stands in the middle of it, "to show to posterity how high rose the mountain levelled by the emperor" (ad declarandum quantæ altitudinis mons et locus sit egestus), I stated that I had been able to estimate the amount of earth and rock removed to make room for the forum at 24,000,000 cubic feet, and concluded, "I have made investigations over the Campagna to discover the place where the twenty-four million cubic feet were carted and dumped, but my efforts have not, as yet, been crowned with success." The place is now discovered. None but an emperor would have dared to bury a cemetery so important as that which I am now describing; and if we remember that it was the open space which was nearest of all to Trajan's excavations, easy of access, that the burying of a cemetery for a necessity of state could be justified by the proceedings of Mæcenas and Augustus, described on page 67 of the same book, and that the change must have taken place at the beginning of the second century, as proved by the dates, and by the construction and type of tombs belonging respectively to the lower and upper strata, I think that my surmise may be accepted as an established fact.

Thus vanished the mausoleum of the Lucilii from the eyes and from the memory of the Romans of the second century. Towards the end of the fourth century the Christians, while tunnelling the ground near it, for one of their smaller catacombs, discovered the crypt by accident, and occupied it. The shape of this crypt may be compared to that of Hadrian's mausoleum; that is, it was a hall in the form of a Greek cross, in the centre of the circular structure, and was reached by means of a corridor. The Christians scattered the relics of the first occupants, knocked down their busts, built arcosolia in the three recesses of the Greek cross, and honeycombed with loculi the side walls of the corridor. The transformation was so complete that, when we first entered the corridor, in July, 1886, we thought we had found a wing of the catacombs of S. Saturninus. Some of the loculi were closed with tiles, others with pagan inscriptions which the fossores had found by chance in tunnelling their way into the crypt. Two loculi, excavated near the entrance outside the corridor, contained bodies of infants with magic circlets around their necks. They are most extraordinary objects in both material and variety of shape. The pendants are cut in bone, ivory, rock crystal, onyx, jasper, amethyst, amber, touch-stone, metal, glass, and enamel; and they represent elephants, bells, doves, pastoral flutes, hares, knives, rabbits, poniards, rats, Fortuna, jelly-fish, human arms, hammers, symbols of fecundity, helms, marbles, boar's tusks, loaves of bread, and so on.

The vicissitudes of the mausoleum did not end with this change of religion and ownership. Two or three centuries ago, when the fever of discovering and ransacking the catacombs of the Via Salaria was at its height, some one found his way to the crypt, and committed purely wanton destruction. The arcosolia were dismantled, and the loculi violated one by one. We found the bones of the Christians of the fourth century scattered over the floor, and, among them, the marble busts of Lucilius Pætus and Lucilia Polla, which the Christians of the fourth century had knocked from their pedestals. Such is the history of Rome.

THE APPIAN WAY AND THE CAMPAGNA

Via Appia. A delightful afternoon excursion in the vicinity of the city can be made to the Valle della Caffarella from the so-called "Tempio del Dio Redicolo" to the "Sacred Grove" by S. Urbano. Leaving Rome by the Porta S. Sebastiano, and turning to the left directly after passing the chapel of Domine quo vadis, we descend to the valley of the river Almo, now called the Valle della Caffarella, from the ducal family who owned it before the Torlonias. The path is full of charm, running, as it does, along the banks of the historical stream, and between hillsides which are covered with evergreens, and scented with the perfume of wild flowers. The place is secluded and quiet, and the solitary rambler is unconsciously reminded of Horace's stanza (Epod. II.):—

"Beatus ille, qui procul negotiis,Ut prisca gens mortalium,Paterna rura bobus exercet suis,Solutus omni fœnore,· · · · ·Forumque vitat, et superba civiumPotentiorum limina."In no other capital of the present day can the sentiment expressed by Horace be felt and enjoyed more than in Rome, where it is so easy to forget the worries and frivolities of city life by walking a few steps outside the gates. The Val d'Inferno and the Via del Casaletto, outside the Porta Angelica, the Vigne Nuove outside the Porta Pia, and the Valle della Caffarella, to which I am now leading my readers, all are dreamy wildernesses, made purposely to give to our thoughts fresher and healthier inspirations. Sometimes indistinct sounds from the city yonder are borne to our ears by the wind, to increase, by contrast, the happiness of the moment. And it is not only the natural beauty of these secluded spots that fascinates the stranger: there are associations special to each which increase its interest tenfold. At the Vigne Nuove one can locate within a hundred feet the spot in which Nero's suicide took place. The Val d'Inferno brings back to our memory the two Domitiæ Lucillæ, their clay-quarries and brick-kilns, of which the products were shipped even to Africa; the Valle della Caffarella is full of souvenirs of Herodes Atticus and Annia Regilla, who are brought to mind by their tombs, by the sacred grove, by the so-called Grotto of Egeria, and by the remains of their beautiful villa.

Herodes Atticus, born at Marathon a. d. 104, of noble Athenian parents, became one of the most distinguished men of his time. Philostratos, the biographer of the Sophists, gives a detailed account of his life and fortunes at the beginning of Book II. Inscriptions relating to his career have been found in Rome, on the borders of the Appian Way, the best-known being the Iscrizioni greche triopee ora Borghesiane, edited by Ennio Quirino Visconti in 1794.136 His father, Tiberius Claudius Atticus Herodes, lost his fortune by confiscation for reasons of state, and was therefore obliged, at the beginning of his career, to depend upon the fortune of his wife, Vibullia Alcia, for his support. Suddenly he became the richest man in Greece, and probably in the world. Many writers have given accounts of his extraordinary discovery of treasure, which was made in the foundations of a small house which he owned at the foot of the Akropolis, near the Dionysiac Theatre. He seems to have been more frightened than pleased at the amount found, knowing how complicated was the jurisprudence on this subject, and how greedy provincial magistrates were. He addressed himself in general terms to the emperor Nerva, asking what he should do with his discovery. The answer was that he could make use of it as he pleased. Even then he was not reassured, and wrote again to the emperor declaring that the fortune was far beyond his condition in life. Nerva's answer confirmed him emphatically in the full possession of this wealth. Herodes did much good with it, as a noble revenge for the persecutions which he had undergone in his younger days; and at his death his son inherited, with the fortune, his generous instincts and kindliness.

Curiosity leads us to inquire where this amount of gold and treasure came from, who it was that concealed it in the rock of the Akropolis, and when, and for what reason. Visconti's surmise that it was hidden there by a wealthy Roman, during the civic wars, and the proscriptions which followed them towards the end of the Republic, is obviously incorrect. No Roman general, magistrate, or merchant of republican times could have collected such a fortune in impoverished Greece. I have a more probable suggestion to make. When Xerxes engaged his fleet against the Greek allies in the straits of Salamis, he was so confident of gaining the day that he established himself comfortably on a lofty throne on the slope of Mount Ægaleos to witness the fight. And when he saw Fortune turn against his forces, and was obliged to retire in hot haste, trusting his own safety to flight, I suppose that the funds of war, which were kept by the treasurer of the army at headquarters, may have been buried in a cleft of the Akropolis, in the hope of a speedy and more successful return. The amount of money carried by Xerxes' treasury officials for purposes of war must have been enormous, when we consider that 2,641,000 men were counted at the review held in the plains of Doriskos.

Whatever may have been the origin of the wealth of Atticus it could not have fallen into better hands. His liberality towards men of letters, and needy friends; his works of general utility executed in Greece, Asia Minor, and Italy; his exhibitions of games and entertainments in the Circus and in the Amphitheatre, did not prevent him from cultivating science to such an extent that, on his arrival in Rome, he was selected as tutor of the two adopted sons of Antoninus Pius,—Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus. Here he married Annia Regilla, one of the wealthiest ladies of the day, by whom he had six children. She died in childbirth, and Herodes was accused, we do not know on what ground, of having accelerated or caused her death by ill-treatment or violence. Regilla's brother, Appius Annius Bradua, consul a. d. 160, brought an action of uxoricide against Herodes, but failed to prove his case. Still, the calumny remained in the mind of the public. To dispel it, and to regain his position in society, Herodes, although stricken with grief, made himself conspicuous almost to excess in honoring the memory of his departed wife. Her jewels were offered to Ceres and Proserpina; and the land which she had owned between the Via Appia and the valley of the Almo was covered with memorial buildings, and also consecrated to the gods. On the boundary line of the property, columns were raised bearing the inscription in Greek and Latin:—

"To the memory of Annia Regilla, wife of Herodes, the light and soul of the house, to whom these lands once belonged."137

The lands are described in other epigraphic documents as containing a village named Triopium, wheat-fields, vineyards, olive-groves, pastures, a temple dedicated to Faustina the younger under the title of the New Ceres, a burialspace for the family, placed under the protection of Minerva and Nemesis, and lastly a grove sacred to the memory of Regilla.

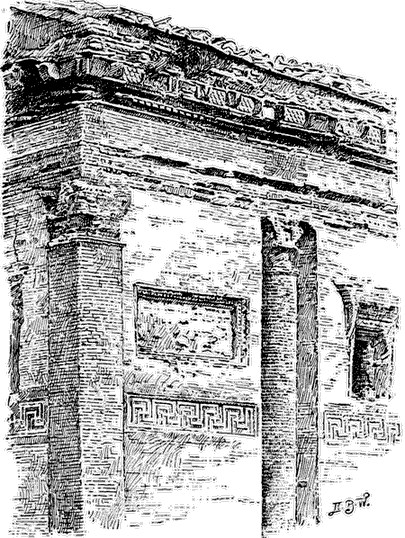

Tomb of Annia Regilla (fragment).

Many of these monuments are still in existence. The first structure we meet with is a tomb of considerable size built in the shape of a temple, the lowest steps of which are watered by the Almo. Its popular name of "Temple of the God Rediculus" is derived from a tradition which points to this spot as the one at which Hannibal turned back before the gates of Rome, and where a shrine to the "God of Retreat" was subsequently raised by the Romans. The Campagna abounds in sepulchral monuments of a similar design, but none can be compared with this in the elegance of its terra-cotta carvings, which give it the appearance and lightness of lace. The polychrome effect produced by the alternate use of dark red and yellow bricks is particularly fine.

Although no inscription has been found within or near this heroön, there are reasons to prove that it was the family tomb of Regilla, Herodes, and their six children. A more beautiful and interesting structure is hardly to be found in the Campagna, and I wonder why so few visit it. Perhaps it is better that it should be so, because its present owner has just rented it for a pig-pen.

Higher up the valley, on a spur of the hill above the springs of Egeria, stands the Temple of Ceres and Faustina, now called S. Urbano alla Caffarella. It belongs to the Barberinis, who take good care of it, as well as of the sacred grove of ilexes which covers the slope to the south of the springs. The vestibule is supported by four marble pillars, but, the intercolumniations having been filled up by Urban VIII. in 1634, the picturesqueness of the effect is destroyed. Here Herodes dedicated to the memory of his wife a statue, minutely described in the second Triopian inscription, alluded to above. Early Christians took possession of the temple and consecrated it to the memory of Pope Urbanus, the martyr, whose remains were buried close by, in the crypta magna of the Catacombs of Prætextatus. Pope Paschal I. caused the Confession of the church to be decorated with frescoes representing the saint from whom it was named, with the Virgin Mary, and S. John. In the year 1011 the panels between the pilasters of the cella were covered with paintings illustrating the lives and martyrdoms of Cæcilia, Tiburtius, Valerianus and Urbanus, and, although injured by restorations, these paintings form the most important contribution to the history of Italian art in the eleventh century. We have therefore under one roof, and within the four walls of this temple, the names of Ceres, Faustina, Herodes and Annia Regilla, coupled with those of S. Cæcilia and S. Valerianus, of Paschal I., and Pope Barberini; decorations in stucco and brick of the time of Marcus Aurelius; paintings of the ninth and eleventh centuries; and all this variety of wealth intrusted to the care of a good old hermit, whose dreams are surely not troubled by the conflicting souvenirs of so many events.

I need not remind the reader that the name of Egeria, given to the nymphæum below the temple, is of Renaissance origin. The grotto in which, according to the legend, and to Juvenal's description, Numa held his secret meetings with the nymph Egeria, was situated within the line of the walls of Aurelian, and in the lower grounds of the Villa Fonseca, that is to say, at the foot of the Cælian Hill, near the Via della Ferratella. I saw it first in 1868, and again in 1880 when collecting materials for my volume on the "Aqueducts and Springs of Ancient Rome."138 In 1887 it was buried by the military engineers, while they were building their new hospital near Santo Stefano Rotondo. The springs still make their way through the newly-made ground, and appear again in the beautiful nymphæum of the Villa Mattei (von Hoffmann) at the corner of the Via delle Mole di S. Sisto and the Via di Porta S. Sebastiano.

As regards the Sacred Grove, there is no doubt that its present beautiful ilexes continue the tradition, and flourish on the very spot of the old grove, sacred to the memory of Annia Regilla, CVIVS HAEC PRAEDIA FVERVNT.

The Sacred Grove and the Temple of Ceres; now S. Urbano alla Caffarella.

To come back, however, to the "Queen of the Roads:" among the many discoveries that have taken place in the cemeteries which line it, that made on April 16, 1485, during the pontificate of Innocent VIII., remains unrivalled.

There have been so many accounts published by modern writers139 in reference to this extraordinary event that it may interest my readers to learn the truth by reviewing the evidence as it stands in its original simplicity. I shall only quote such authorities as enable us to ascertain what really took place on that memorable day. The case is in itself so unique that it does not need amplification or the addition of imaginary details. Let us first consult the diary of Antonio di Vaseli:—

(f. 48.) "To-day, April 19, 1485, the news came into Rome, that a body buried a thousand years ago had been found in a farm of Santa Maria Nova, in the Campagna, near the Casale Rotondo.... (f. 49.) The Conservatori of Rome despatched a coffin to Santa Maria Nova elaborately made, and a company of men for the transportation of the body into the city. The body has been placed for exhibition in the Conservatori palace, and large crowds of citizens and noblemen have gone to see it. The body seems to be covered with a glutinous substance, a mixture of myrrh and other precious ointments, which attract swarms of bees. The said body is intact. The hair is long and thick; the eyelashes, eyes, nose, and ears are spotless, as well as the nails. It appears to be the body of a woman, of good size; and her head is covered with a light cap of woven gold thread, very beautiful. The teeth are white and perfect; the flesh and the tongue retain their natural color; but if the glutinous substance is washed off, the flesh blackens in less than an hour. Much care has been taken in searching the tomb in which the corpse was found, in the hope of discovering the epitaph, with her name; it must be an illustrious one, because none but a noble and wealthy person could afford to be buried in such a costly sarcophagus thus filled with precious ointments."

Translation of a letter of messer Daniele da San Sebastiano, dated MCCCCLXXXV:—

"In the course of excavations which were made on the Appian Way, to find stones and marbles, three marble tombs have been discovered during these last days, sunk twelve feet below the ground. One was of Terentia Tulliola, daughter of Cicero; the other had no epitaph. One of them contained a young girl, intact in all her members, covered from head to foot with a coating of aromatic paste, one inch thick. On the removal of this coating, which we believe to be composed of myrrh, frankincense, aloe, and other priceless drugs, a face appeared, so lovely, so pleasing, so attractive, that, although the girl had certainly been dead fifteen hundred years, she appeared to have been laid to rest that very day. The thick masses of hair, collected on the top of the head in the old style, seemed to have been combed then and there. The eyelids could be opened and shut; the ears and the nose were so well preserved that, after being bent to one side or the other, they instantly resumed their original shape. By pressing the flesh of the cheeks the color would disappear as in a living body. The tongue could be seen through the pink lips; the articulations of the hands and feet still retained their elasticity. The whole of Rome, men and women, to the number of twenty thousand, visited the marvel of Santa Maria Nova that day. I hasten to inform you of this event, because I want you to understand how the ancients took care to prepare not only their souls but also their bodies for immortality. I am sure that if you had had the privilege of beholding that lovely young face, your pleasure would have equalled your astonishment."

Translation of a letter, dated Rome, April 15, 1485, among Schedel's papers in Cod. 716 of the Munich library:

"Knowing your eagerness for novelties, I send you the news of a discovery just made on the Appian Way, five miles from the gate, at a place called Statuario (the same as S. Maria Nova). Some workmen engaged in searching for stones and marbles have discovered there a marble coffin of great beauty, with a female body in it, wearing a knot of hair on the back of her head, in the fashion now popular among the Hungarians. It was covered with a cap of woven gold, and tied with golden strings. Cap and strings were stolen at the moment of the discovery, together with a ring which she wore on the second finger of the left hand. The eyes were open, and the body preserved such elasticity that the flesh would yield to pressure, and regain its natural shape immediately. The form of the body was beautiful in the extreme; the appearance was that of a girl of twenty-five. Many identify her with Tulliola, daughter of Cicero, and I am ready to believe so, because I have seen, close by there, a tombstone with the name of Marcus Tullius; and because Cicero is known to have owned lands in the neighborhood. Never mind whose daughter she was; she was certainly noble and rich by birth. The body owed its preservation to a coating of ointment two inches thick, composed of myrrh, balm, and oil of cedar. The skin was white, soft, and perfumed. Words cannot describe the number and the excitement of the multitudes who rushed to admire this marvel. To make matters easy, the Conservatori have agreed to remove the beautiful body to the Capitol. One would think there is some great indulgence and remission of sins to be gained by climbing that hill, so great is the crowd, especially of women, attracted by the sight.

"The marble coffin has not yet been removed to the city; but I am told that the following letters are engraved on it: 'Here lies Julia Prisca Secunda. She lived twenty-six years and one month. She has committed no fault, except to die.' It seems that another name is engraved on the same coffin, that of a Claudius Hilarus, who died at forty-six. If we are to believe current rumors, the discoverers of the body have fled, taking with them great treasures."

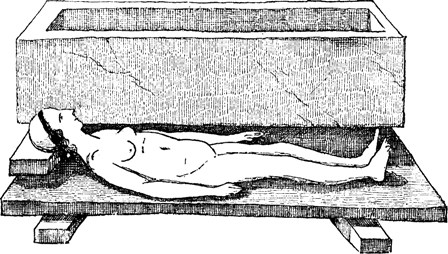

And now let the reader gaze at the mysterious lady. The accompanying cut represents her body as it was exhibited in the Conservatori palace, and is taken from an original sketch in the Ashburnham Codex, 1174, f. 134.

The body of a girl found in 1485.

Celio Rodigino, Leandro Alberti, Alexander ab Alexandro and Corona give other particulars of some interest:—

The excavations were undertaken by the monks of Santa Maria Nuova (now S. Francesca Romana), five miles from the gate. The tomb stood on the left or east side of the road, high above the ground. The sarcophagus was imbedded in the walls of the foundation, and its cover was sealed with molten lead. As soon as the lid was removed, a strong odor of turpentine and myrrh was remarked by those present. The body is described as well arranged in the coffin, with arms and legs still flexible. The hair was blonde, and bound by a fillet (infula) woven of gold. The color of the flesh was absolutely lifelike. The eyes and mouth were partly open, and if one drew the tongue out slightly it would go back to its place of itself. During the first days of the exhibition on the Capitol this wonderful relic showed no signs of decay; but after a time the action of the air began to tell upon it, and the face and hands turned black. The coffin seems to have been placed near the cistern of the Conservatori palace, so as to allow the crowd of visitors to move around and behold the wonder with more ease. Celio Rodigino says that the first symptoms of putrefaction were noticed on the third day; and he attributes the decay more to the removal of the coating of ointments than to the action of the air. Alexander ab Alexandro describes the ointment which filled the bottom of the coffin as having the appearance and scent of a fresh perfume.

These various accounts are no doubt written under the excitement of the moment, and by men naturally inclined to exaggeration; still, they all agree in the main details of the discovery,—in the date, the place of discovery, and the description of the corpse. Who was, then, the girl for the preservation of whose remains so much care had been taken?

Pomponio Leto, the leading archæologist of the age, expressed the opinion that she might have been either Tulliola, daughter of Cicero, or Priscilla, wife of Abascantus, whose tomb on the Appian Way is described by Statius (Sylv. V. i. 22). Either supposition is wrong. The first is invalidated by the fact that the body was of a young and tender girl, while Tulliola is known to have died in childbirth at the age of thirty-two. Moreover, there is no document to prove that Cicero had a family vault at the sixth milestone of the Appian Way. The tomb of Priscilla, wife of Abascantus, a favorite freedman of Domitian, is placed by Statius near the bridge of the Almo (Fiume Almone, Acquataccio) four and a half miles nearer the gate; where, in front of the Chapel of Domine quo vadis, it has been found and twice excavated: the first time in 1773 by Amaduzzi; the second in 1887, under my supervision. The only clew worth following is that given in Pehem's letter of April 15, now in the Munich library; but even this leads to no result. The inscription, which was said to mention the name and age of the girl, is perfectly genuine, and duly registered in the "Corpus Inscriptionum," No. 20,634. It is as follows:—