полная версия

полная версияA Manual of the Operations of Surgery

Excision of the Hip-Joint.—The question as to the propriety of performing this operation in any case is still debated by some surgeons, and the selection of suitable cases for the operation is greatly modified by the varying opinions of the different schools of surgery. Enough here to describe the method of operating, and the amount of the bone which is to be removed.

As in the shoulder-joint, the head of the femur is much more liable to disease, and, as a rule, much earlier attacked than is the acetabulum, but unfortunately the acetabulum does eventually become affected also in probably a much larger proportionate number of cases than the glenoid. Caries of the head, neck, and trochanters of the femur is a very common disease in this variable climate, and frequently connected with the strumous taint. After much suffering, abscesses form and discharge, giving considerable pain, and often end by carrying off the patient. As a result of the abscess and destruction of the ligaments, the head of the bone is apt to be displaced, and under some sudden muscular exertion or involuntary spasm, consecutive dislocation of the femur (generally on to the dorsum ilii) very often occurs.

In such a case the operation of excision of the head of the femur is by no means difficult, and not excessively dangerous, especially in young children.

Operation.—It is hardly necessary, or indeed possible, to lay down exact rules for the performance of this operation, in so far as the external incisions are concerned, for the sinuses which exist ought in general to be made use of.

When the surgeon has his choice, a straight incision (Plate II. fig. a.), parallel with the bone, extending from the top of the great trochanter downwards for about two inches, and also from the same point in a curved direction with the concavity forwards, upwards towards the position of the head of the bone (see diagram), will be found most convenient. The incisions should be carried boldly down to the bone, which will often be felt exposed and bathed in pus, any remains of the ligamentous structures must be cautiously divided with a probe-pointed bistoury, and then by bringing the knee of the affected side forcibly across the opposite thigh, with the toes everted, the head of the bone is forced out of the wound. The head, neck, and great trochanter should be fully exposed, and the saw applied transversely below the level of the trochanter, so as to remove it entire. If this is not done, it prevents discharge, protrudes at the wound, and besides this it is almost invariably diseased along with the head. Chain saws are quite unnecessary, it being in most cases easy to apply an ordinary one to the bone, if it is properly everted.

Great care in the after-treatment is required to prevent undue shortening of the limb, or in the event of a cure to secure the most favourable position for the anchylosis. The femur occasionally tends to protrude at the wound, and hence may require to be counter-extended by splints. If required at all, the splint should be made with an iron elbow opposite the wound to admit of its being easily dressed. In most cases counter-extension may be best managed by a weight and pulley.

Various forms of hammock swings to support the whole body, and slings of leather or canvas to support the limb only, have been found to aid recovery, and render the patient much more comfortable.

When the acetabulum is also diseased the prognosis is much more unfavourable than when it is sound.

The experiments of Heine and Jäger on the dead body, and operations by Hancock, Erichsen, and Holmes, on patients, have shown that in cases of extensive disease of the acetabulum it is quite possible by a prolonged and careful dissection to remove it all without injury of the pelvic viscera.

The details of incisions for such an operation need scarcely be given, as they must vary in each case with the amount of bone diseased, and the position of the already existing sinuses. The amount of bone that may be removed varies much. Erichsen in one case excised "the upper end of the femur, the acetabulum, the rami of the pubis, and of the ischium, a portion of the tuber ischii, and part of the dorsum ilii."62

A less formidable proceeding may be useful in cases where the acetabulum is diseased, but not deeply. The moderate use of an ordinary gouge may succeed in removing the diseased bone.

Experience and the cold evidence of statistics prove, however, that the prognosis in any case is modified very much for the worse by the presence of any disease of the acetabulum, more than one-half of the cases proving fatal in which it is diseased, whether attempts to remove the disease of the acetabulum be made or not, and that those cases do best in which the head of the femur has been displaced, and lies outside the joint almost like a loose sequestrum among the soft parts.

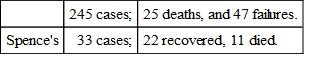

The results of excision of the hip have as yet been very discouraging, the mortality of the whole series of published cases being, according to Dr. Hodge's careful table, very little under 1 in every 2 cases, viz., 1 in 2-5/53. Later statistics are however more favourable.

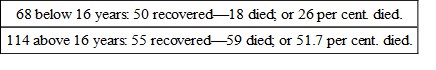

Like all other excisions, the mortality increases very much with the patient's age.

Thus of 103 completed cases in which the age is given, 53 recovered and 50 died, but dividing the cases at the end of the sixteenth year, we find that of the children below this age 43 recovered and 29 died, a mortality of 40.2 per cent.; of the adults, 10 recovered, and 21 died, or a mortality of 67.6 per cent.

If we remember the marvellous power of recovery from joint diseases we find in childhood, under the influence of good diet, cod-liver oil, and fresh air, we cannot shut our eyes to the fact that such results and such a mortality are by no means encouraging.

From an extensive experience in a special hospital for hip-disease, where fresh air, abundant nourishment, and very excellent nursing are provided, the author is learning more and more to trust to the power of nature in the cure of even very advanced cases of hip-disease in children, and he believes that operation is rarely necessary, or even warrantable, except for the removal of sequestra.

Mr. Holmes's63 statistics are interesting. He has operated on no fewer than nineteen cases. Of these seven died, one after secondary amputation at the hip. Another required amputation and recovered. Two others died of other diseases without having used their limb. Of the remaining nine, three were perfectly successful, four were promising cases, and two unpromising.

Professor Spence in 19 cases had 6 deaths, or a mortality of 31.6 per cent.

Culbertson's collection gives out of 426 cases, 192 deaths, or 45 per cent.

Mr. Croft, whose skill and success as an operator are well known, has recorded 45 cases of excision of hip in his own practice; of these 16 died, 11 were under treatment, 18 had recovered, of which 16 had moveable joints and useful limb; the other two are "potentially cured."64

Various other incisions have been devised for gaining access to the joint. The most noticeable are those in which a flap is made instead of a linear incision. Sedillot makes a semilunar or ovoid flap, the base of which is just below the great trochanter, and which includes it, the convexity being upwards and the flap being turned down. Gross's modification of this is preferable, being turned the opposite way, the convexity being downwards (Plate III. fig. e.), and the flap thus being turned up.

Results in successful cases.—Of fifty-two in Hodge's table, thirty-one had useful limbs, six indifferent, three decidedly useless, four died within three years, and of the remaining eight no details are given.

The shortening is always considerable, a high-heeled shoe being required in most cases; a stick is indispensable; in many, crutches are necessary.

Various operations have been devised for the treatment of osseous anchylosis of the hip-joint when in a bad position. All are more or less dangerous. Perhaps one of the least dangerous is the plan of subcutaneous division of the neck of the femur by a narrow saw, proposed by Mr. Adams of London. It is sometimes a very laborious operation.

Excision of Knee-Joint.—Removal of Bone.—In every case the excision of the joint ought to be complete. Some attempts have been made to save one or other of the articular surfaces, but they have proved failures. The patella has frequently been left when it was not diseased, as is often the case, but the results have not been such as to recommend such a practice.

Direction of Section of the Bones.—The bones should be cut transversely, and, as far as possible, be in accurate and complete apposition. A slight bevelling at the expense of the posterior margin will produce an anchylosis of the limb in a very slightly flexed position, which is found to aid the patient in walking.

It has been proposed by some65 to cut both bones obliquely, so as to obviate the difficulty of making the transverse surfaces parallel. This involves a still greater practical difficulty in keeping these oblique surfaces in position during the after-treatment.

This plan might possibly be valuable in cases where the disease was limited to one or other edge of the bone.

Among the various incisions recommended, the best seems to be the Semilunar Incision.

Operation.—The limb being held in an extended position, a single semilunar incision (Plate I. fig. b.) is made, entering the joint at once, and dividing the ligamentum patellæ. It should extend from the inner side of the inner condyle of the femur to a corresponding point over the outer one, passing in front of the joint midway between the lower edge of the patella and tuberosity of the tibia. The flap is then dissected back, the ligaments divided, when by extreme flexion of the limb the articular surface of the tibia and femur are thoroughly exposed. The crucial ligaments must then be divided cautiously, and the articular portion of the femur cleaned anteriorly by the knife, posteriorly by the operator's finger, so far as possible to avoid injury of the artery. The whole articular surface of the femur must then be removed by a transverse cut with the saw as exactly as possible at a right angle with the axis of the bone. The amount of the femur which will require removal will in the adult vary from an inch to an inch and a half or even more. It must involve all the bone normally covered by cartilage; and this being removed, if the section shows evidence of disease, slice after slice may require removal till a healthy surface is obtained. Occasionally, if the diseased portion appears limited, though deep, the application of a gouge may succeed in removing disease without involving too great shortening of the limb. Specially in children, it is of great importance to avoid removing the whole epiphysis. The tibia must then be exposed in a similar manner, and a thin slice removed; if the bone be tolerably healthy, even less than half an inch will prove quite sufficient.

This method has an immense advantage in that it provides an excellent anterior flap for the amputation, which may be required in cases where the disease of bone is found too extensive to admit of the excision being practised.

This method, with slight deviations, is substantially that of Richard Mackenzie of Edinburgh, Wood of New York, Jones of Jersey.

Hæmorrhage must then be stopped, and that as thoroughly as possible, by torsion, cold, and pressure, and the flap brought accurately together with sutures.

In some rare cases, it may be found necessary to divide the hamstring tendons to rectify spastic contraction of the muscles; but this can generally be done quite well from the original wound.

Holt makes a dependent opening in the popliteal space for drainage. This is unnecessary if the incisions are made sufficiently far back, and if the wound is properly drained. It is unsafe, as approaching so close to the artery and veins. If much bagging takes place, the use of a drainage-tube will prove quite sufficient.

After-treatment.—Wire splints lined with leather and provided with a foot-piece; special box-splints with moveable sides, as Butcher's;66 plaster-of-Paris moulds are used by Dr. P.H. Watson67 of Edinburgh and others; this last form of dressing is the best, and allows the limb to be suspended from a Salter's swing.

H-shaped incision.—The internal incision should commence at a point about two inches below the articular surface of the tibia, and in a line with its inner edge; it should then be carried up along the femur in a direction parallel to the axis of the extended limb, so as to pass in front of the saphena vein, and thus avoid it, for a distance of five inches. The external incision, commencing just below the head of the fibula, must be carried upwards parallel to the preceding for the same distance. Both incisions must be made by a heavy scalpel with a firm hand, so as to divide all the tissues down to the bone. The vertical incisions are then united by a transverse one passing across just below the lower angle of the patella. The flaps thus formed must then be dissected up and down, and the internal and external lateral ligaments divided, thus thoroughly opening the joint and exposing the crucial ligaments. These must be divided carefully, remembering the position of the artery. The bones are then to be cleared and divided, as in the operation already described. This is the method of Moreau and Butcher.68

Patella and Ligamentum Patellæ retained.—"A longitudinal incision, full four inches in extent, was made on each side of the knee-joint, midway between the vasti and flexors of the leg; these two cuts were down to the bones, they were connected by a transverse one just over the prominence of the tubercle of the tibia, care being taken to avoid cutting by this incision the ligamentum patellæ; the flap thus defined was reflected upwards, the patella and the ligament were then freed and drawn over the internal condyle, and kept there by means of a broad, flat, and turned-up spatula; the joint was thus exposed, and after the synovial capsule had been cut through as far as could be seen, the leg was forcibly flexed, the crucial ligaments, almost breaking in the act, only required a slight touch of the knife to divide them completely. The articular surfaces of the bones were now completely brought to view, and the diseased portions removed by means of suitable saws, the soft parts being hold aside by assistants."69

Results of Excision of Knee-joint:—Holmes's Table of recent cases from 1873-1878—

Buck's Operation for Anchylosed Knee-Joint.—The principle of this operation is to remove a triangular portion of bone, which is to include the surfaces of the femur and tibia, which have anchylosed in an awkward position, and by this means to set the bones free, and enable the limb to be straightened. Access to the joint may be obtained by either of the two methods already described. Sections of the bones are then to be made with the saw, so as to meet posteriorly a little in front of the posterior surface of the anchylosed joint, and thus remove a triangular portion of bone; the portion still remaining, and which still keeps up the deformity, is then to be broken through as best you can, either by a chisel, or a saw, or forced flexion. The ends are to be pared off by bone-pliers, and the surfaces brought into as close apposition as possible. The operation is a difficult one, a gap being generally left between the anterior edges of the bones, from the unyielding nature of the integuments behind, and the difficulty of removing the posterior projecting edges from their close proximity to the artery. Of twenty cases on record, eight died, and two required amputation.

Relation of Age to result in Excision of Knee-Joint from Hodge's Tables.

Of 182 complete cases:—

Excision of the Ankle-Joint.—In what cases is it to be done, and how much bone is to be removed?

In cases of compound dislocation of the ankle-joint, the tibia and fibula are apt to be protruded either in front or behind. When this happens it is a dislocation generally very difficult to reduce, and when reduced to retain in position. In such cases, if there seems to be any chance of retaining the foot, excision of the articular ends of tibia and fibula greatly add to the probabilities in its favour. It may be done without any new wound, and, in general, by an ordinary surgeon's saw.

When the astragalus does not protrude, it seems to matter little for the future result whether its articular surface be removed or not. When, on the other hand, it protrudes, as a result either of the displacement of the entire foot, or of a dislocation complete or partial of the astragalus itself, there is no doubt that excision either of its articular surface or of the entire bone will give very excellent results. Jäger reports twenty-seven such cases, with only one fatal, and one doubtful result.

In cases of disease of the Ankle-joint.—Excision has been performed a good many times, and should in most cases be complete. A work like this is not the place to discuss the propriety of operations so much as the method of performing them, but one remark may be permitted. Few points of surgical diagnosis are more difficult than it is to tell whether in any given case disease is confined to the ankle-joint, and whether or not the bones of the tarsus participate. If they do even to a slight extent, no operation which attacks the ankle-joint only has any reasonable chance of success. It may look well for a time, but sinuses remain, the irritation of the operation only hastens the progress of the disease of the bone, and the result will almost certainly be disappointing, amputation being almost the inevitable dernier ressort.

Methods of Operating:—

Mr. Hancock has been very successful by the following method:—

Commence the incision (Plate II. figs. B.B.) about two inches above and behind the external malleolus, and carry it across the instep to about two inches above and behind the internal malleolus. Take care that this incision merely divides the skin, and does not penetrate beyond the fascia. Reflect the flap so made, and next cut down upon the external malleolus, carrying your knife close to the edge of the bone, both behind and below the process, dislodge the peronei tendons, and divide the external lateral ligaments of the joint. Having done this, with the bone-nippers cut through the fibula, about an inch above the malleolus, remove this piece of bone, dividing the inferior tibio-fibular ligament, and then turn the leg and foot on the outside. Now carefully dissect the tendons of the tibialis posticus and flexor communis digitorum from behind the internal malleolus. Carry your knife close round the edge of this process, and detach the internal lateral ligament, then grasping the heel with one hand, and the front of the foot with the other, forcibly turn the sole of the foot downwards, by which the lower end of the tibia is dislocated and protruded through the wound. This done, remove the diseased end of the tibia with the common amputating saw, and afterwards with a small metacarpal saw placed upon the back of the upper articulating process of the astragalus, between that process and the tendo Achillis, remove the former by cutting from behind forwards. Replace the parts in situ; close the wound carefully on the inner side and front of the ankle; but leave the outside open, that there may be a free exit for discharge, apply water-dressing, place the limb on its outer side on a splint, and the operation is completed.

Skin, external, and internal ligaments, and the bones are the only parts divided, no tendons and no arteries of any size.70

Barwell's method by lateral incisions is briefly as follows:—

On the outer side, an incision over the lower three inches of the fibula turns forward at the malleolus at an angle, and ends about half an inch above the base of the outer metatarsal. The flap is to be reflected, fibula divided about two inches from its lower end by the forceps, and dissected out, leaving peronei tendons uncut. A similar incision on the inner side terminates over the projection of the internal cuneiform bone; the sheaths of the tendons under inner angle are then to be divided, and the artery and nerve avoided; the internal lateral ligament is then to be divided, the foot twisted outwards, so as to protrude the astragalus and tibia at the inner wound. The lower end of the tibia and top of the astragalus are to be sawn off by a narrow-bladed saw passing from one wound to the other.71

Dr. M. Buchanan of Glasgow has described an operation by which the joint can be excised through a single incision over the external malleolus.

Results.—So far as can be gathered from cases already published, the results are very often (at least in one out of every two cases) unsatisfactory. Sinuses remain, which do not heal, the limbs are useless, and amputation is in the end necessary.

Langenbeck has performed it sixteen times during the last Schleswig-Holstein war (in 1864), and the Bohemian war in 1866, with only three deaths. In these cases the operation was subperiosteal.

Excision of the Scapula.—More or less of the scapula has in many cases been removed along with the arm, and even with the addition of portion of the clavicle.

Excision of the entire bone, leaving the arm, has been performed in two instances by Mr. Syme. The procedure must vary according to the nature and shape of the tumour on account of which the operation is performed. Mr. Syme operated as follows:—

In the first case, one of cerebriform tumour of the bone, he "made an incision from the acromion process transversely to the posterior edge of the scapula, and another from the centre of this one directly downwards to the lower margin of the tumour. The flaps thus formed being reflected without much hæmorrhage, I separated the scapular attachment of the deltoid, and divided the connections of the acromial extremity of the clavicle. Then, wishing to command the subscapular artery, I divided it, with the effect of giving issue to a fearful gush of blood, but fortunately caught the vessel and tied it without any delay. I next cut into the joint and round the glenoid cavity, hooked my finger under the coracoid process, so as to facilitate the division of its muscular and ligamentous attachments, and then pulling back the bone with all the force of my left hand, separated its remaining attachments with rapid sweeps of the knife." (Plate III. fig. g.)

Mr. Syme's second case was also one of tumour of the scapula; the head of the humerus had been excised two years before.

He removed it by two incisions, one from the clavicle a little to the sternal side of the coracoid, directed downwards to the lower boundary of the tumour, another transversely from the shoulder to the posterior edge of the scapula. The clavicle was divided at the spot where it was exposed, and the outer portion removed along with the scapula.72

The author has in a case of osseous tumour removed the whole body of the scapula, leaving glenoid, spine, acromion and anterior margin with excellent result and a useful arm.

Large portions of the shafts of the humerus, radius, and ulna have been removed for disease or accident, and useful arms have resulted; but as the operative procedures must vary in every case, according to the amount of bone to be removed, and the number and position of the sinuses, no exact directions can be given.

For very interesting cases of such resections reference may be made to Wagner's treatise on the subject, translated and enlarged by Mr. Holmes, and to Williamson's Military Surgery, p. 227.

Excision of Metacarpals and Phalanges.—To excise the metacarpal implies that the corresponding finger is left. Except in cases of necrosis, where abundance of new bone has formed in the detached periosteum, the results of such excisions do not encourage repetition, the digits which remain being generally very useless. It is quite different, however, if it is the thumb that is involved; and every effort should, in every case, be made to retain the thumb, even in the complete absence of its metacarpal bone. For the good results of a case in which Mr. Syme excised the whole metacarpal bone for a tumour, see his Observations in Clinical Surgery, p. 38.