Полная версия

Three men in a boat / Трое в лодке, не считая собаки. Книга для чтения на английском языке

The next morning we read that it was going to be a “warm, fine day; much heat;” and we put light clothing on, and went out, and, half-an-hour after we had started, it began raining hard, and an extremely cold wind sprang up, and both would keep on steadily for the whole day, and we came home with colds and rheumatism all over us, and went to bed.

The weather is a thing that is beyond me63 altogether. I never can understand it. The barometer is useless: it is as misleading as the newspaper forecast.

There was one barometer hanging up in a hotel at Oxford at which I was staying last spring, and, when I got there, it was pointing to “set fair64.” It was simply pouring with rain outside, and had been all day; and I couldn’t quite make matters out65. I tapped the barometer, and it jumped up and pointed to “very dry.” I tapped it again the next morning, and it went up still higher, and the rain came down faster than ever. On Wednesday I went and hit it again, and the pointer went round towards “set fair,” “very dry,” and “much heat,” until it was stopped by the peg, and couldn’t go any further. It tried its best, it evidently wanted to go on, and prognosticate drought, and water famine, and sunstroke, and such things, but the peg prevented it, and it had to be content with pointing to the commonplace “very dry.”

Meanwhile, the rain came down in a steady torrent, and the lower part of the town was under water, because the river had overflowed. The fine weather never came that summer. I expect that machine must have been referring to the following spring.

Then there are those new styles of barometers, the long straight ones. I never can make head or tail of those66. There is one side for 10 a.m. yesterday and one side for 10 a.m. today; but you can’t always get there as early as ten, you know. It rises or falls for rain and fine, with much or less wind, and if you tap it, it doesn’t tell you anything. And you’ve to correct it to sea-level, and reduce it to Fahrenheit, and even then I don’t know the answer.

But who wants to be foretold the weather? When it becomes bad enough, we don’t want to have the misery of knowing about it beforehand. The prophet we like is the old man who, on the particularly gloomy-looking morning of some day when we particularly want it to be fine, looks round the horizon with a particularly knowing eye, and says:

“Oh no, sir, I think it will clear up all right. It will break67 all right enough, sir.”

“Ah, he knows”, we say, as we wish him good morning, and start off; “wonderful how these old fellows can tell!”

And we feel affection for that man which is not at all lessened by the circumstances of its not clearing up, but continuing to rain steadily all day.

“Ah, well,” we feel, “he did his best.”

Of the man that prophesies us bad weather, on the contrary, we have only bitter and revengeful thoughts.

“Going to clear up, do you think?” we shout, joyfully, as we pass.

“Well, no, sir; I’m afraid it’s settled down68 for the day,” he replies, shaking his head.

“Stupid old fool!” we mutter, “what’s he know about it?” And, if his words prove correct, we come back feeling still more angry with him, and with a vague feeling that, somehow or other, he has had something to do with69 it.

It was too bright and sunny on this especial morning for George’s gloomy readings about bad weather to upset us very much: and so, finding that he could not disappoint us, and was only wasting his time, he stole the cigarette that I had carefully rolled up for myself, and went.

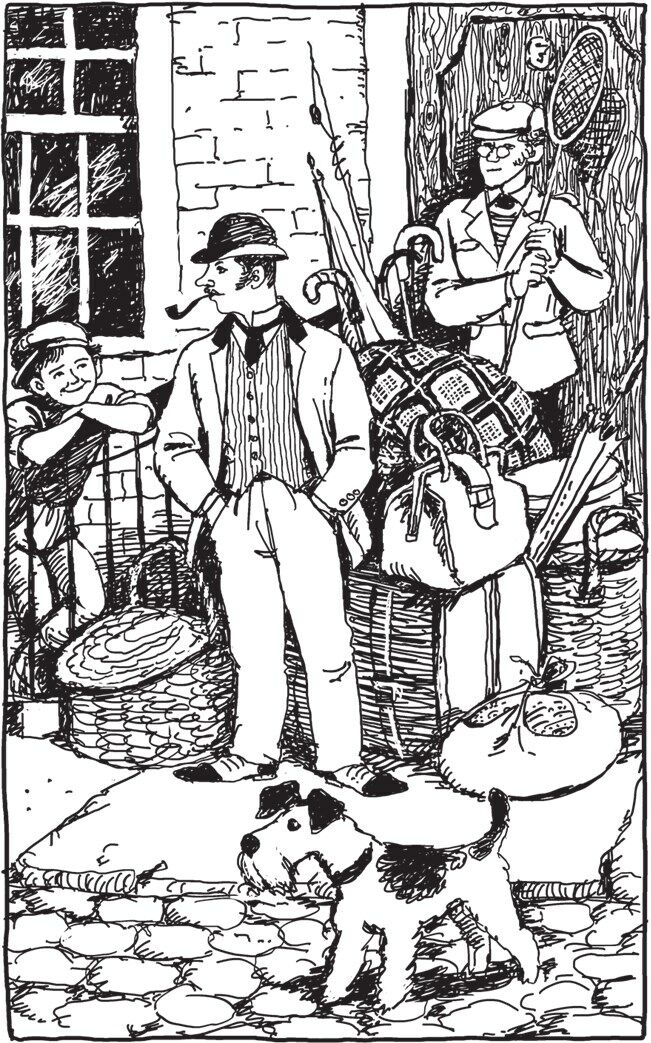

Then Harris and I, having finished up the few things left on the table, carried out our luggage on to the doorstep, and waited for a cab.

There seemed a good deal of luggage, when we put it all together. There was the Gladstone70 and the small hand-bag, and the two hampers, and a large roll of rugs, and some four or five overcoats and mackintoshes, and a few umbrellas, and then there was a melon by itself in a bag, because it was too bulky to go in anywhere, and a couple of pounds of grapes in another bag, and a Japanese paper umbrella, and a frying pan, which, being too long to pack, we had wrapped round with brown paper.

It did look a lot, and Harris and I began to feel rather ashamed of it, though why we should be, I can’t see. No cab came by, but the street boys did, and got interested in the show, apparently, and stopped.

Biggs’s boy was the first to come round. Biggs is our greengrocer, and his chief talent is to obtain the services of the most abandoned and unprincipled errand-boys71 that civilisation has ever produced. If anything more than usually wicked in the boy line happens in our neighbourhood, we know that it is Biggs’s latest boy. I was told that, at the time of the Great Coram Street murder72, it was quickly concluded by our street that Biggs’s boy (for that period) was at the bottom of it73. In reply to the severe cross-examination to which he was subjected, when he came for orders the morning after the crime, he managed to prove a complete alibi. Otherwise it would have gone hard with him. I didn’t know Biggs’s boy at that time, but, from what I have seen of them since, I should not have attached much importance to that alibi74 myself.

Biggs’s boy, as I have said, came round the corner. He was evidently in a great hurry, but, on catching sight of Harris and me, and Montmorency, and the things, he stopped up and stared. Harris and I frowned at him. This might have wounded a more sensitive nature, but Biggs’s boys are not, as a rule, touchy. He came to a dead stop, a yard from our step, and, leaning up against the railings, and fixed his eyes on us, he evidently meant to see this thing out75.

In another moment, the grocer’s boy passed on the opposite side of the street. Biggs’s boy cried to him:

“Hi! They are moving.”

The grocer’s boy came across, and took up a position on the other side of the step. Then the young gentleman from the boot-shop stopped, and joined Biggs’s boy.

“They are not going to starve, are they?” said the gentleman from the boot-shop.

By this time, quite a small crowd had collected, and people were asking each other what was the matter. One party (the young and silly portion of the crowd) held that it was a wedding, and pointed out Harris as the bridegroom; while the elder and more thoughtful inclined to the idea that it was a funeral, and that I was probably the corpse’s brother.

At last, an empty cab turned up (it is a street where, as a rule, and when they are not wanted, empty cabs pass at the rate of three a minute, and hang about, and get in your way), and packing ourselves and our belongings into it, and keeping out a couple of Montmorency’s friends, who had evidently sworn never to leave him, we drove away surrounded by the cheering crowd. Biggs’s boy threw a carrot after us for luck.

We got to Waterloo at eleven, and asked where the eleven-five train started from. Of course nobody knew; nobody at Waterloo ever knows where a train is going to start from, or where a train is going to, or anything about it. The porter who took our things thought it would go from number two platform, while another porter, with whom he discussed the question, had heard a rumour that it would go from number one. The station-master, on the other hand76, was convinced it would start from the local platform.

To put an end to the matter77, we went upstairs, and asked the traffic superintendent, and he told us that he had just met a man, who said he had seen it at number three platform. We went to number three platform, but the authorities there said that they thought that train was the Southampton express, or else the Windsor loop. But they were sure it wasn’t the Kingston train, though why they were sure they couldn’t say.

Then our porter said he thought that it must be on the high-level platform; said he thought he knew the train. So we went to the high-level platform, and saw the engine-driver78, and asked him if he was going to Kingston. He said he couldn’t say for certain of course, but that he rather thought he was. Anyhow, if he wasn’t the 11.05 for Kingston, he said he was pretty confident he was the 9.32 for Virginia Water, or the 10 a.m. express for the Isle of Wight, or somewhere in that direction, and we should all know when we got there. We slipped half-a-crown into his hand, and begged him to be the 11.05 for Kingston.

“Nobody will ever know, on this line,” we said, “what you are, or where you’re going. You know the way, you slip off79 quietly and go to Kingston.”

“Well, I don’t know, gentlemen,” replied the noble fellow, “but I suppose some train has to go to Kingston; and I’ll do it. Give me the half-crown.”

Thus we got to Kingston by the London and South-Western Railway. We learnt, afterwards, that the train we had come by was really the Exeter mail, and that they had spent hours at Waterloo, looking for it, and nobody knew what had become of it.

Our boat was waiting for us at Kingston just below bridge, and we went to it, and we stored our luggage round it, and we stepped into it.

“Are you all right, sir?” said the man.

“Right it is,” we answered; and with Harris at the sculls and I at the tiller-lines, and Montmorency, unhappy and deeply suspicious, in the prow80, we started our travel on to the waters which, for a fortnight, were to be our home.

Exercises1. Read the chapter and mark the sentences T (true), F (false) or NI (no information).

1. The narrator was going to get up at 9 o’clock.

2. George was still sleeping when his friends woke up.

3. Montmorency ate chops and cold beef for breakfast.

4. The narrator considers weather forecasts to be very useful.

5. The narrator had a good time staying in a hotel in Oxford.

6. We usually prefer people who prophesy good weather, even if their words don’t prove correct.

7. The friends gathered quite a small crowd to help them with the luggage.

8. There wasn’t any timetable at Waterloo station.

9. The friends had to pay an engine-driver to get to Kingston.

10. George was deeply suspicious at the beginning of the sea trip.

2. Learn the words from the text:

fortnight, interrupt, waste, instead of, weather forecast, occasional, beforehand, meanwhile, wonder, pay attention to, circumstance, afterwards, rumour, on the contrary, beg, convinced, suspicious, prove, grocer, starve.

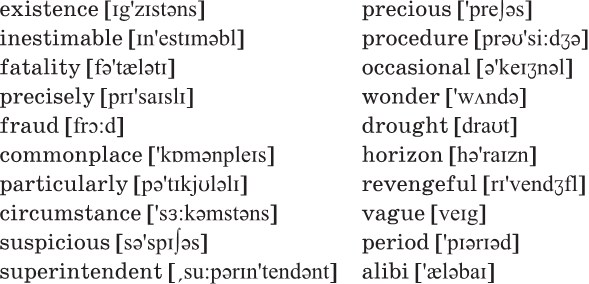

3. Practice the pronunciation of the following words.

4. Fill in the gaps using the words from the text.

1. It … Mrs. Poppets … woke me up next morning.

2. If I … … you, you’d … lain there for the whole fortnight.

3. He … have been up … himself with eggs and bacon or … the dog instead … sprawling there.

4. We told him that he … have … go without shaving that morning, as we … going to unpack that bag again for him.

5. Montmorency … … two other dogs to come and see him, and they … whiling away the time by … on the doorstep.

6. And so, finding that he … not disappoint us, and … only … his time, he … the cigarette that I … carefully rolled up for …, and … .

7. There … a melon by itself in a bag, because it was … bulky … go in anywhere.

8. … this time, quite a small crowd … collected, and people … asking each … what … the matter.

9. The porter … took our things thought it … go from number two platform, while another porter … heard a rumour that it … … from number one.

10. We learnt … the train we … come by was really the Exeter mail, and that they had … hours at Waterloo, looking … it, and nobody … what … become of it.

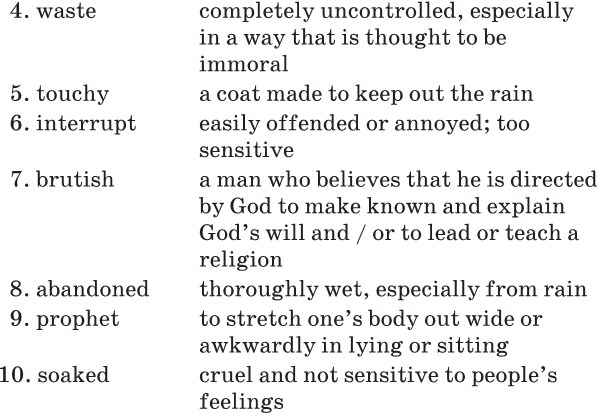

5. Match the words with definitions.

6. Find in the text the English equivalents for:

прогноз погоды, мне интересно (почему…), вместо того (чтобы), поздняя осень, обращать внимание на, местная газета, оставаться дома, тратить драгоценное время, сказать наверняка, проспать, знать заранее, злиться на кого-то.

7. Find the words in the text for which the following are synonyms:

respond, foretell, annoying, soaked, obtain, apparently, ordinary, decide, cry, extremely.

8. Explain and expand on the following.

1. It was Mrs. Poppets that woke me up next morning.

2. I do think that this “weather-forecast” fraud is about the most annoying.

3. The barometer is useless: it is as misleading as the newspaper forecast.

4. But who wants to be foretold the weather?

5. Then Harris and I carried out our luggage on to the doorstep, and waited for a cab.

6. By this time, quite a small crowd had collected.

7. Nobody at Waterloo ever knows where a train is going to start from.

8. We learnt, afterwards, that the train we had come by was really the Exeter mail.

9. Answer the following questions.

1. Did the friends wake up at the time they planned? Why / why not?

2. Why did Harris and the narrator decide to save George?

3. What is the narrator’s attitude to weather forecasts? Why?

4. How did the narrator and his friends spend the holiday he recollects about?

5. What does the narrator think about barometers and weather foretelling?

6. What show did the street boys get interested in? Who was the first?

7. What kind of people Biggs’s boys usually were?

8. Did the friends face any problem at Waterloo station? What was it?

9. How did the friends get to Kingston?

10. Was Montmorency happy to start the journey?

10. Retell the chapter for the persons of the narrator, Biggs’s boy, George, Harris, Montmorency.

CHAPTER VI

It was a wonderful morning, late spring or early summer, as you care to take it81. The attractive streets of Kingston, where they came down to the water’s edge, looked quite picturesque in the flashing sunlight, the river with its barges, the neat villas on the other side, Harris, in a red and orange blazer, grunting away at the sculls82, the distant glimpses of the grey old palace of the Tudors83, all made a sunny picture, so bright but calm, so full of life, and yet so peaceful.

I thought about Kingston, or “Kyningestun,” as it was once called in the days when Saxon kings were crowned there. Great Caesar crossed the river Thames there, and the Roman legions camped upon its hills. Caesar like Elizabeth, some years later, seems to have stopped everywhere: only he didn’t stay at the public houses.

The English Queen was crazy about public houses. There’s hardly a pub within ten miles of London that she does not seem to have looked in, or stopped at, or slept at, some time or other. I wonder now, supposing Harris became a great and good man, and got to be Prime Minister, and died, if they would put up signs over the public houses that he had visited: “Harris had a glass of beer in this house;” “Harris had two glasses of Scotch whisky here in the summer of ’88;” “Harris was thrown away from here in December, 1886.”

No, there would be too many of them! The houses that he had never entered would become famous. “The only house in South London that Harris never had a drink in!” The people would rush to it to see what could have been the matter with it.

Saxon kings were crowned in Kingston but then its greatness passed away for a time, to rise once more when Hampton Court84 became the palace of the Tudors and the Stuarts85. Many of the old houses speak of those days when Kingston was a royal town, and nobles and courtiers lived there, near their King, and the long road to the palace gates was cheerful all day with clanking steel and rustling silks and velvets, and fair faces. The spacious houses, with their large windows, their huge fireplaces, and their gabled roofs86 were constructed in the days “when men knew how to build.” The hard red bricks have only become more firm with time, and their oak stairs do not creak and grunt when you try to go down them quietly.

Speaking of oak staircases reminds me that there is a magnificent carved oak87 staircase in one of the houses in Kingston. It is a shop now but it was evidently once the mansion of some great person. A friend of mine, who lives in Kingston, went in there to buy a hat one day, and, in a thoughtless moment, put his hand in his pocket and paid for it then and there88.

The shopman (he knows my friend) was naturally a little amazed at first; but, quickly recovering himself, and feeling that something ought to be done to encourage this sort of thing, asked our hero if he would like to see some fine old carved oak. My friend said he would, and the shopman took him through the shop, and up the staircase of the house. The balusters were a brilliant piece of art, and the wall all the way up was oak-paneled, with carving that would have done credit to89 a palace.

From the stairs, they went into the drawing-room, which was a large, bright room, decorated with startling though cheerful blue paper. There was nothing, however, remarkable about the room, and my friend wondered why he had been brought there. The owner went up to the paper, and tapped it. It gave a wooden sound.

“Oak,” he explained. “All carved oak, right up to the ceiling, just the same as you saw on the staircase.”

“But, good heavens! man,” protested my friend; “you don’t mean to say you have covered over carved oak with blue wallpaper?”

“Yes,” was the reply: “it was an expensive work. But the room looks cheerful now. It was awful gloomy before.”

I can’t say I altogether blame the man. From his point of view90, which is of the average householder, desiring to take life as lightly as possible, there is reason on his side. Carved oak is very pleasant to look at, and to have a little of, but it is no doubt somewhat depressing to live in, for those who aren’t fond of it. It would be like living in a church.

No, what was sad in his case was that he, who didn’t care for carved oak, should have his drawing-room paneled with it, while people who do care for it have to pay enormous prices to get it. It seems to be the rule of this world. Each person has what he doesn’t want, and other people have what he does want.

Married men have wives, and don’t seem to want them; and young single fellows cry out that they can’t get them. Poor people who can hardly keep themselves91 have eight hearty children. Rich old couples, with no one to leave their money to, die childless.

Then there are girls with lovers. The girls that have lovers never want them. They say they would rather be without them, that they bother them, and why don’t they go and make love to Miss Smith and Miss Brown, who are plain and elderly, and haven’t got any lovers? They themselves don’t want lovers. They never mean to marry.

It does not do to dwell on these things92; it makes one so sad.

There was a boy at our school, we used to call him Sandford and Merton93. His real name was Stivvings. He was the most extraordinary fellow I ever came across. I believe he really liked study. He used to get into awful rows for sitting up in bed and reading Greek; and as for French irregular verbs there was simply no keeping him away from them. He was full of weird and unnatural ideas about being a credit to his parents and an honour to the school; and he desired to win prizes, and grow up and be a clever man, and had all those sorts of weak-minded ideas. I never knew such a strange creature, yet harmless as the babe unborn94.

Well, that boy used to get ill about twice a week, so that he couldn’t go to school. There never was such a boy to get ill as that Sandford and Merton. If there was any known disease going within ten miles of him, he had it, and had it badly. He would take bronchitis in the dog days95, and have hay-fever at Christmas; and he would go out in a November fog and come home with sunstroke.

They put him under laughing gas one year, poor fellow, and drew all his teeth, and gave him a false set, because he suffered so terribly with toothache; and then it turned to neuralgia and earache. He was never without a cold, except once for nine weeks while he had scarlet fever96. During the great cholera scare of 1871, our neighborhood was the only one free from it. There was only one case in the whole parish: that case was young Stivvings.

He had to stay in bed when he was ill, and eat chicken and custards; and he would lie there and sob, because they wouldn’t let him do Latin exercises, and took his German grammar away from him.

And we other boys, who would have given ten terms of our school life for being ill for a day couldn’t catch so much as a stiff neck97. We fooled about in draughts, and it did us good, and freshened us up; and we took things to make us sick, and they made us fat, and gave us an appetite. Nothing we could think of seemed to make us ill until the holidays began. Then, on the first day, we caught colds, and severe cough, and all kinds of disorders, which lasted till the term started again; when suddenly we would get well again, and be better than ever.

Such is life; and we are as grass that is cut down, and put into the oven and baked.

To go back to the carved oak question, our great-great-grandfathers must have had very fair notions of the artistic and the beautiful. Why, all our art treasures of today are only the usual items of three or four hundred years ago. I wonder if there is real beauty in the old soup plates, beer mugs, and candle snuffers98 that we prize now, or if it is only the halo of age glowing around them that gives them their charms in our eyes99. The pink shepherds and the yellow shepherdesses that we hand round now for all our friends to admire, and pretend they understand, were the unvalued mantel ornaments100 that the mother of the eighteenth century would have given the baby to suck when he cried.

Will it be the same in the future? Will the prized treasures of today always be the cheap trifles of the day before? Will rows of our willow pattern dinner plates101 be ranged above the chimneypieces of the great in the twenty-first century? Will the white cups with the gold rim and the beautiful gold flower inside (species unknown) be carefully mended and dusted only by the lady of the house?

That china dog that ornaments the bedroom of my furnished apartments. It is a white dog. Its eyes are blue. Its nose is a delicate red, with spots. Its head is painfully erect; its expression is nearly imbecile. I do not admire it myself. Considered as a work of art, I may say it irritates me. Thoughtless friends laugh at it, and even my landlady herself has no admiration for it, and excuses its presence by the circumstance that her aunt gave it to her.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

1

hay fever – сенная лихорадка (аллергическая реакция на пыльцу растений)

2

St. Vitus’s Dance – пляска святого Витта, хорея (нервное заболевание)

3

housemaid’s knee – воспаление коленного сустава (болезнь типична для людей, часто встающих на колени, например, домохозяек, горничных)

4

to do a good turn – оказать хорошую услугу

5

lb = pound – фунт (1 фунт = 0,45 кг)

6

pt = pint – пинта (1 пинта ≈ 0,5 л)

7

And don’t stuff up your head with things you don’t understand. – И не забивай себе голову вещами, в которых не разбираешься.

8