полная версия

полная версияKatharine Frensham: A Novel

"But grand, Herr Sorenskriver," said Katharine, "with nothing petty."

"Nei da!" he said, looking pleased. "It would be nice to think that this was as true of ourselves as of our mountains."

Then they glanced back at the snow-clad Rondane in the distance; and they came out into the open country, and saw the Jutenheim (the home of the giants) in front of them. They had left the region of the firs, pines, and birches, and reached the land of the dwarf-birch, the willow, and the persistent juniper. And here the rough carriage-road ended; for the sanatorium, where the fashionable Scandinavians were taking their summer mountain-holiday, was now only a few yards off. The saeter pilgrims had thought of dining there; but no one seemed inclined to face a crowd of two hundred guests. So the little company drew up by the side of a brook, and ate Mysost14 sandwiches; the Sorenskriver, who continued in the best of good humours, assuring Katharine that this was an infallible way of learning Norwegian quickly. Alan was disappointed that he was not rude.

"Then we could go for him," he said privately to Katharine.

"Oh, perhaps he may even yet be rude!" whispered Katharine, reassuring him.

When they had lunched and taken their ease, they started once more on their journey, passing the precincts of the sanatorium in order to hire boats for crossing the beautiful mountain lake; for F – was on the other side, perched high up on the mountain-slope. By rowing over, they would save themselves about two miles of circuitous rough road. Jens said that he would take the gig and the horses round by the road to meet the boat. Alan went with him, but he looked back wistfully at Katharine once or twice.

And now a curious thing happened. As Katharine and Gerda were standing waiting for their boat, the sound of English voices broke upon them.

"English," said Gerda. "That is a greeting for you."

"Well, it's very odd," said Katharine, listening; "but I've heard that voice before."

"Perhaps you think it is familiar because it is English," suggested Gerda.

"Perhaps," answered Katharine; but she was still arrested by the sound.

"I thought the Sorenskriver said that no English people came here?" she said.

"He said they came very rarely to these parts," Gerda replied. "One or two Englishmen for fishing sometimes; otherwise Swedes, Danes, Finns, Russians."

"I am sure I have heard that voice before," Katharine said. She seemed troubled.

"There they go, you see," Gerda said, pointing to two figures. "They were in the little copse yonder – two of your tall Englishwomen. How distinctly one hears voices at this height! Well, the Kemiker is waiting for us. Du milde Gud! Look at my Ejnar handling the oars! Bravo, Ejnar!"

"Come, ladies," called Clifford cheerily from the boat. "Let us be off before the Botaniker upsets the boat. He has been trying to reach a plant at the bottom of the lake."

When they had taken their places, Katharine turned to Clifford, who was looking radiantly happy, and she said:

"Row quickly, row quickly, Professor Thornton. I want to get away from here."

"Do you dislike the great caravanserai so much?" he said. "Well, you have only to turn round, and there you have the Jutenheim mountains in all their glory. Are they not beautiful?"

She looked at the snow-capped mountains; but for the moment their beauty scarcely reached her. She was thinking of that voice. When had she heard it? And where?

"The mountains, the mountains of Norway!" cried Clifford. "Ah, I've always loved the North, and each time I come I love it more passionately, and this time – "

No one was listening to him. Gerda and Ejnar were busy trying to see what was in the bottom of the lake, and Katharine seemed lost in her own thoughts. Suddenly she remembered where she had heard that voice. It was Mrs Stanhope's. The words rushed to her lips; she glanced at Clifford, saw and felt his happiness, and was silent. But now she knew why the sound of that voice had aroused feelings of apprehension and anxiety, and an instinctive desire to ward off harm both from the man and the boy.

For directly she heard it, she had been eager to hurry Clifford away, and relieved that Alan had gone on with Jens.

CHAPTER X

So they rowed across the lake, he remembering nothing except the joy of being with her, and she trying to forget that any discord of unrest had broken in upon the harmonies of her heart. They landed on swampy ground, and made their way over rare beautiful mosses, ling, and low growth of bilberry and cloudberry. Ejnar and Gerda became lost to all human emotions, and gave themselves up to the joys of their profession. Long after all the rest of the little company had met on the rocky main road to the Saeters, the two botanists lingered in that fairyland swamp. At last Jens and Alan were sent back to find them, and in due time they reappeared, with a rapt expression on their faces and many treasures in their wallets. The country grew wilder and grimmer as the pilgrims mounted higher. The road, or track, was very rough, scarcely fit for a cariole or stol-kjaerre, and the Swedish mathematical Professor felt anxiously concerned about the comfort and safety of the little Swedish artist, who was a bad walker, and who therefore preferred to jolt along in the gig. But she did not mind. She laughed at his fears, and whispered to Katharine with her pretty English accent:

"My lover is afraid for my safeness!"

And Katharine laughed and whispered back:

"I hope you are having a really good flirtation with him."

"Ja, ja," she answered softly, "like the English boy says 'reeping good!'"

Grimmer and wilder still grew the mountainous country. They had now passed the region of the dwarf-birch and willow-bushes, and had come to what is called the "lichen zone," where the reindeer-moss predominates, and where the bushes are either creeping specimens, growing in tussocks, or else hiding their branches among the lichens so that only the leaves show above them. It seemed almost impossible to believe that here, on these more or less barren mountain-plateaus, good grazing could be found for the cattle during the summer months. Yet it was true enough that in this particular district the cows and goats of about fifty Saeters found their summer maintenance, about fifty of the great Gaards down in the side valleys of the Gudbrandsdal owning, since time immemorial, portions of the mountain grazing-land. The Sollis' Saeter was not in this region. It was fifty miles distant from the Solli Gaard, and, as Jens told the pilgrims, took two whole days to reach, over a much rougher country than that which they had just traversed.

"This is nothing," said Jens smiling grimly, when the Swedish lady was nearly thrown out of the gig on to Svarten's back. "We call this a good road; and it goes right up to the first Saeter. Then you can drive no more. Now you see the smoke rising from the huts. We are there now."

Jens, usually so reserved and silent, was quite animated. The mountain-air, and the feeling of being in the wild, free life he loved so much, excited him. He was transformed from a quiet, rather surly lad into an inspired human being fitted to his own natural environment. Gerda, looking at him, thought immediately of Björnson's Arne.

"You love the mountains, Jens?" she said to him.

"Yes," he answered simply. "I am always happy up at the Saeter. One has thoughts."

They halted outside the first Saeter, and turned to look at the beautiful scene. They were in the midst of low mountains. In the distance, across the lake, they could see the snow-peaks of the great Jutenheim range – the home of the giants. Around them rose strange weird mountain forms, each one suggestive of wayward and grim fancy. And over to the right, towering above a group of castle-mountains, peopled with strange phantoms born of the loneliness and the imagination, they saw the glistening peaks of the Rondane caught by the glow of the sun setting somewhere – not there. And below them was another mountain-lake, near which nestled two or three Saeters apart from the rest, and in which they could see the reflection of the great grey-blue clouds edged with gold. And above them passed in tumultuous procession the wonders of a Norwegian mountain evening sky of summer-time: clouds of delicate fabric, clouds of heavy texture: calm fairy visions, changing imperceptibly to wild and angry spectacle: sudden pictures of fierce and passionate joy, and lingering impressions of deepest melancholy, – all of it faithfully typical of the strange Norwegian temperament.

"One must have come up to the mountains," whispered Clifford to Katharine, "to understand anything at all of the Norwegian mind. This is the Norwegians, and the Norwegians are this."

And the grim old Sorenskriver, standing on the other side of Katharine, said in his half-gruff, half-friendly way:

"Fröken, you see a wild and uncompromising Nature, without the gentler graces. It is ourselves."

"And again I say, with nothing petty in it," said Katharine, spreading out her arms. "On a big scale – vast and big – the graces lost in the greatness."

"Look," said Jens, "the goats and cows are beginning to come back to the Saeters. They have heard the call. You will see them come from all directions, slowly and in their own time."

Slowly and solemnly they came over the fields, a straggling company, each contingent led by a determined leading lady, who wore a massive collar and bell. She looked behind now and again to see if her crowd of supernumeraries were following her at sufficiently respectful distances, and then she bellowed, and waited outside her own Saeter. The saeter pilgrims stood a long time looking at this characteristic Norwegian scene: the wild heath in front of them was literally dotted with far-off specks, which gradually resolved themselves into cows or goats strolling home in true Norwegian fashion —largissimo lentissimo! Even as stars reveal themselves in the sky, and ships on the sea, if one stares long and steadily, so these cows and goats revealed themselves in that great wild expanse. And just when there seemed to be no more distant objects visible, suddenly something would appear on the top of a hillock, and Jens would cry with satisfaction:

"See, there is another one!" He looked on as eagerly as all the strangers, very much as an old salt gazing fixedly out to sea. Then some of the saeter-girls came out to urge the lingering animals to hurry themselves, and the air was filled with mysterious cries of coaxment and impatience. At last the pilgrims went to inquire about food and lodging for the night.

"You may get it perhaps," Jens remarked vaguely. This, of course, was the Norwegian way of saying that they would get it; and when they knocked at the door of the particular Saeter which Jens pointed out to them, a dear old woman welcomed them to her stue (hut) as though it were a palace. She liked to have visitors, and her only regret was that she had not known in time to prepare the room for them in best saeter fashion. Meanwhile, if they would rest, she would do her utmost; and she suggested that the gentlemen should go down to the Saeter by the lake and secure a lodging there, and then they could return and have their meal in the stue here. She was a pretty old woman. Pleasure and excitement lit up her sweet face and made her eyes wonderfully bright. She wanted to know all about her visitors, and Gerda explained that they were Swedes, Danes, and English, and one Norwegian only, the Sorenskriver. She was deeply interested in Katharine, and asked Gerda whether the English Herr and the boy were Katharine's husband and son; and when Gerda said that they were only friends, she seemed disappointed, and patted Katharine on the shoulder in token of sympathy with her. Gerda told Katharine, and Katharine laughed. She was very happy and interested. She had forgotten the sound of that jarring voice. All her gaiety and bonhomie had come back to her. It was she who began to help their pretty old hostess. It was she who sprinkled the fresh juniper-leaves over the floor, throwing so many that she had to be checked in her reckless generosity. Then Gerda fetched the logs, and made a grand fire in the old Peise (stone fireplace), and almost immediately the warmth brought out the sweet fragrance of the juniper-leaves. The old woman spread a fine woven cloth over the one bed in the room. Then she bustled into the dairy and brought out mysost – a great square block of it, and fladbröd, and coffee-berries, which Katharine roasted and then crushed in the machine. When the table had been set, the old woman brought a bowl of cream and sugar, and the "vaffle" irons, and began to make vaffler (pancakes). She filled three large plates with these delicious dainties, and her eager face was something to behold. Finally she signed to Katharine, who followed her into the dairy, and came back carrying two wooden bowls of römmekolle – milk with cream on the top turned sour.

"Now," she said triumphantly, "everything is ready. And here come the Herrer. And now you will want some fresh milk. The cows have just been milked."

"No, no, thou hast done enough. I will go and fetch the milk," said the Sorenskriver, who was in great spirits still, and almost like a young boy. "Why, thou dear Heaven, I was a cotter's son and lived up at the Saeter summer after summer. This is like my childhood again. I am as happy as Jens!"

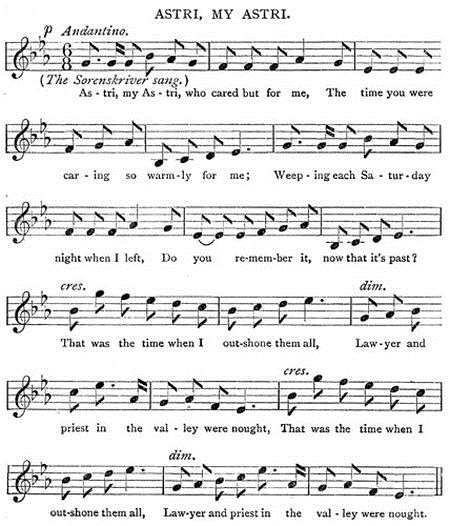

So off he went to the cowhouse at the other end of the little saeter-enclosure. He began to sing a stev15 with the milkmaids. This was the stev: —

(The milkmaids answered) —

The time you were caring for Astri alone,Was the time when that Svanaug you cared not to see;The time when your steps were so active and brisk,Hastening to greet me each Saturday eve.That was the time when no riches on earth,Fair could have seemed without my sweetheart's love.That was the time when no riches on earth,Fair could have seemed without my sweetheart's love.He returned with two jugs of milk. A merry laugh sounded after him, and he was smiling too. The saeter-door was divided into two parts, and he shut the lower half to keep out the draught; and when the old woman tried to slip away, leaving her guests to enjoy themselves in their own fashion, he said:

"No, no, mor, thou must stay." And every one cried out:

"Thou must stay."

So she stayed. She tidied herself, folded a clean white silk kerchief crosswise over her head, and took her place at the table, dignified and charming in her simple ease of manner. Many an ill-bred low-born, and ill-bred well-born society dame might have learnt a profitable lesson from this old saeter-woman – something about the unconscious grace which springs from true unself-consciousness. And she smiled with pride and pleasure to see them all doing justice to the vaffler, the mysost, the fladbröd, and the römmekolle. She was particularly anxious that the English lady should enjoy the römmekolle.

"Stakkar!" she said. "Thou must eat the whole of the top! Ja, saa, with sugar on it! It is good. Thou canst not get it so good in thy country? Thou hast no mountains there, no Saeters there? Ak, ak, that must be a poor sort of country! Well, we cannot all be born in Norway."

And she laughed to see Alan pegging away at the vaffler.

"The English boy shall have as many vaffler as he likes," she said. "Wilt thou have some more, stakkar? I will make thee another plateful."

It was a merry, merry meal. Every one was hungry and happy. The Sorenskriver asked for some spaeke-kjöd (smoked and dried mutton or reindeer) which was hanging up in the Peise. He cut little slices out of it and made every one eat them.

"Otherwise," he said, "you will know nothing about a Norwegian Saeter. And now a big piece for myself! Isn't it good, Botaniker? Ah, if you eat it up, you will be inspired to find some rare plants here!"

Then they all drank the old saeter-woman's health.

"Skaal!" they said.

And then Clifford said:

"Skaal to Norway!"

And the Sorenskriver said:

"Skaal to England!"

And the botanists said:

"Skaal to Sweden!"

And the Swedish professor said:

"Skaal to Denmark!"

Then the Sorenskriver added:

"Would that all the nations could meet together up at the Saeter and cry 'Skaal!'"

And at that moment there came a knock at the door, and a little man in English knickerbockers and Norfolk jacket asked for admittance.

"English, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, German?" asked the Sorenskriver.

"Monsieur, je suis un peintre français," said the little man, somewhat astonished.

"Then Skaal to France!" cried the merry company, draining their coffee-cups.

The Frenchman, with that perfect tact characteristic of his nation, thanked them in the name of his country, his hand on his heart; and took his place amongst these strangers, at their invitation. And then they gathered round the fire and heaped up the logs. Katharine never forgot that evening: the five nations gathered together in that quaint low room built of huge tree-trunks roughly put together, with lichen and birch-leaves filling in the crevices: the curious mixture of languages; the fun of understanding and misunderstanding: the fragrance of the juniper: the delightful sense of good fellowship: the happiness of being in the presence of the man she loved: the mysterious influence of the wild mountains: the loosening of pent-up instincts and emotions. Years afterwards she was able to recall every detail of the surroundings: the Lur (horn) hanging on the wall, and in those parts still used for calling to the cattle; the Langeleik (an old kind of zither) in its own special recess, seldom found missing in real old Norwegian houses, silent now, but formerly playing an important part in the saeter-life of bygone days; the old wooden balances, which seemed to belong to the period of the Ark; the sausages and smoked meat hanging in the Peise; the branches of fir placed as mats before the door; the saeter-woman passing to and fro, now stopping to speak to one of her guests, now slipping away to attend to some of her many saeter duties. Then at an opportune moment the Sorenskriver said:

"Now, mor, if we heap on the logs, perhaps the green-dressed Huldre will come and dance before the fire. Thou hast seen the Huldre, thou? Tell us about her – wilt thou not?"

But she shook her head mysteriously, and went away as if she were frightened; but after a few minutes she came back, and said in an awed tone of voice:

"Twice I have seen the green-dressed Huldre – ak, and she was beautiful! I was up at the Saeter over by my old home, and my sweetheart had come to see me; and ak, ak, the Huldre came and danced before the fire – and she bewitched him, and he went away into the mountains and no one ever saw him again."

"And so," she added simply, "I had to get another sweetheart."

"Aa ja," said the Sorenskriver. "I expect there was no difficulty about that."

"No," she answered, "thou art right."

And she beat a sudden retreat, as though she had said too much; but she returned of her own accord, and continued:

"And the second time I saw the Huldre it was on the heath. I had gone out alone to look for some of the cows who had not come home, and I saw her on horseback. Her beautiful green dress covered the whole of Blakken's back, and her tail swept the ground. And Blakken flew, flew like lightning. And when I found the cows, they were dying. The Huldre had willed them ill. That was fifty years ago. But I see her now. No one can ever forget the Huldre."

So the evening passed, with stories of the Huldre, and the Trolds, and the mountain-people of Norwegian lore; for here were the strangers in the very birthplace of many of these weird legends, all, or most of them, part and parcel of the saeter-life; all, or most of them, woven out of the wild and lonely spirit of mountain-nature.

And then the little company passed by easy sequence to the subject of visions and dreams. Some one asked Katharine if she had ever had a vision.

"Yes," she answered; "once – once only."

"Tell it," they said.

But she shook her head.

"It would be out of place," she answered, "for, oddly enough, it was about God."

"Surely, mademoiselle," said the Frenchman, "we are far away enough from civilisation to be considered near enough to God for the moment?"

But she could not be induced to tell it.

"You would think I was a religious fanatic," she said. "And I am neither fanatical nor religious."

"Ah," said Ejnar, "I hope I may have a vision tonight of what is in the bottom of that lake we crossed over."

"You did your very best, Professor, to include us all in that vision of the bottom of the lake," said Clifford quaintly.

"My poor Ejnar, how they all tease you!" said Gerda.

"I think," said Katharine, "the Kemiker ought to know better, being himself a scientific man. Probably if he were piloting us all down a mine, he would not care what became of us if his eye lit on some unexpected treasure of the earth-depths."

"Noble lady," said Ejnar, smiling; "I perceive I have a friend in you, and the Kemiker has an enemy."

Clifford Thornton looked into the fire and laughed happily.

Then Gerda said:

"Twice I have dreamed that I found a certain species of fungus in a particular part of the wood; and guided by the memory of my dream, the next day I have found it. Have you ever found anything like that in a dream, Professor Thornton?"

Clifford looked up with a painful expression on his face.

"I always try my very hardest never to dream, Frue," he answered.

"And why?" she asked.

"Because up to the present we appear to have no knowledge of how to control our dreams," he replied.

"But if we could control them, they would not be dreams," said Katharine.

"So much the better then," answered Clifford; "they would be mere continuations of self-guided consciousness in another form."

"But it is their utter irresponsibility and wildness which give them their magic!" cried the French artist. "In my dreams, I am the prince of all painters born since the world began. Mon Dieu, to be without that! I tremble! Life would be impossible! In my dreams I discover unseen, unthought-of colours! I cry with rapture!"

"In my dreams," said the Swedish mathematician, "I find the fourth dimension, the fifth dimension, the hundredth dimension!"

"In my dreams," said the Sorenskriver, waving his arms grandiosely, "I see Norway standing by herself, strong, powerful, irresistible as the Vikinger themselves, no union with a sister country – nei, nei, pardon me, Mathematiker!"

"Why, you would take away the very inspiration of the poet, the very life of the patriot's spirit," said Katharine, turning to Clifford.

"You are all speaking of the dreams which are the outcome of the best and highest part of ourselves," said Clifford, speaking as if he were in a dream himself. "But what about the dreams which are not the outcome of our best selves?"

"Oh, surely they pass away as other dreams," she answered.

"But do you not see," he said, "that if there is a chance that the artist remembers the rapture with which he discovered in his dream that marvellous colour, and the patriot the joy which he felt on beholding in his dreams his country strong and irresistible, there is also a chance that less noble feelings experienced in a dream may also be remembered?"

The Frenchman shrugged his shoulders.

"Mon Dieu!" he said. "We cannot always be noble – not even in our dreams. I, for my part, would rather take the chance of dreaming that I injured or murdered some one and rejoiced over it, than lose the chance of dreaming that I was the greatest artist in the world. Why, I have murdered all my rivals in my dreams, and they are still alive and painting with great éclat pictures entirely inferior to mine! And I am no worse for having assassinated them and rejoiced over my evil deeds in my dream."