полная версия

полная версияKatharine Frensham: A Novel

"Come, Thea!" she cried. "Let us dance the Spring-dance for the good Danish lady to see. Fjeldros and Brungaas can wait a few minutes."

"Nei, nei, nei!" cried old Kari. "It is not safe to dance in the cowhouse, Mette. Thou know'st the Huldre will come and throw stones in at the cows. Thou know'st she will come. Ja, ja, I have seen her do it, and the cows were killed. Ak, I am afraid. The Huldre will come."

"Perhaps," said Mette, winking mischievously at Tante – "perhaps it is better to be on the safe side. All the same, I'm not afraid of the long-tailed Huldre."

"Have you seen her often, Kari?" asked Tante.

"Three times," said Kari, shuddering, "and each time she worked me harm. She is mischievous and ugly, not like the beautiful green-dressed Huldre. I saw her once up at the Saeter, when I was alone and had made a big fire. She came and danced and danced before the fire. But I must not waste my time with thee. I must milk Blomros."

"Kari has been taken away by the mountain people," Mette said, winking again at Tante. "Thou shouldst tell the Danish lady."

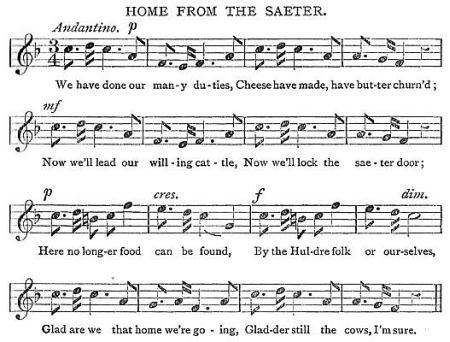

But Kari buried herself under Blomros; and so Mette, still anxious to entertain her visitor, struck up with the pretty little folk-song, "Home from the Saeter."

When they had finished, Knutty looked round and saw Gerda standing listening.

"Now," said Knutty, "you will understand why I come to the cowhouse. It is my concert-room. Well then, my good friends, good-bye for the present."

"Come back to-morrow," cried Mette. "The milking goes so merrily when thou art here."

"And mind, no dancing!" said Knutty, smiling and putting up her hand in warning. "Remember the long-tailed one!"

Mette's merry laughter sounded after them, and was followed by her finale, the mountain-call to the goats:

"Kille bukken, kille bukken, kille bukken! lammet mit!" with a final flourish which would have made a real prima donna ill for a week from jealousy.

"Mette has got a temperament," said Knutty, still smiling. "Thank Heaven for that! Anything is better than your dead-alivers, your decaying vegetable world. No disrespect to you, kjaere, for you look particularly alive this evening; a nice flush on your face – whether anger or joy, no matter – the effect is the same – life."

"Ejnar and I have found some dwarf-birch," said Gerda, pointing to her green wallet.

"Ah, that is certainly a life-giving discovery," remarked Knutty.

"We've had a lovely afternoon together," continued Gerda, "and we've discussed 'Salix' to our hearts' content."

"Ah," said Knutty, "no wonder you look so animated."

"But just by the group of mountain-ashes we met Fröken Frensham," said Gerda, "and Ejnar left me. And I was angry. But as she had the Sorenskriver and your Englishman with her, I didn't mind so much. Oh, it isn't her fault. She doesn't encourage him; and she cannot help being attractive. But Ejnar – "

"Why, my child," said Knutty, "who ever heard of a live woman being jealous, generous, and just? You can't possibly be an animal – nor even a vegetable – you must be a mineral. I have it – gold!"

"Tante," said Gerda, "wait until you have a husband, and then you won't laugh."

"No, I don't suppose I should!" replied Knutty. "Other people would do the laughing for me."

"No," said Gerda. "They should not laugh at you in my presence, I can tell you."

"Ah," said Knutty, "you're pure gold, kjaere. There, don't fret about that wretch Ejnar. If he ran away from you, we could easily overtake him. He'd be stopping to look at all the plants on the wayside; and the lady, no matter who she was, would leave him in disgust. No self-respecting eloping female could stand that, you know. Come. There's the bell ringing for smoked salmon and cheese."

But although Knutty kept up her spirits that evening, she was greatly disturbed by her talk with Alan, and distressed to know how to help him. When she went to her room, she sat for a long time at the window, thinking and puzzling. Not a single helpful idea suggested itself to her. Her heart was full of pity for the boy and concern for the father. She reflected that it was in keeping with Marianne's character to leave this unnecessary trouble behind her: that all the troubles Marianne ever made had always been perfectly unnecessary. And she worked herself into a rage at the mere thought of Mrs Stanhope, Marianne's friend.

"The beast," she said, "the metallic beast! I'd like to see her whole machinery lynched."

After that she could not keep still, but walked up and down her big room, turning everything over in her mind until her brain was nearly distraught. Once she stood rigid for a moment.

"Had Clifford anything to hide about his wife's death?" she asked herself.

"No, no," she replied angrily. "That is ridiculous – I'm a fool to think of it even for a moment."

Her mind wandered back to the time of Marianne's death. She remembered the doctor had said that Marianne had died from some shock.

"Had Clifford lost his self-control that last night when, by his own telling, he and Marianne had some unhappy words together, and had he perhaps terrified her?" she asked herself.

"No, no," she said. "Why do I think of these absurd things?"

But if she thought of them – she, an old woman with years of judgment and experience to balance her – was it surprising that the young boy, worked upon by Mrs Stanhope's words, was thinking of them?

Knutty broke down.

"My poor icebergs," she cried. "I'm a silly, unhelpful old fool, and no good to either of you. I never could tackle Marianne – never could. She was always too much for me; and although she's dead, she is just the same now – too much for me."

She shook her head in despair, and the tears streamed down her cheeks; but after a few minutes of profound misery she brightened up.

"Nå," she said, brushing her tears away, "of course, of course! Why was I forgetting that dear Katharine Frensham? I was forgetting that I saw daylight. What an old duffer I am! If I cannot help my icebergs, she can – and will. If I cannot tackle Marianne, she can."

Her thoughts turned to Katharine with hope, affection, admiration, and never a faintest touch of jealousy. She had been drawn to her from the beginning; and each new day's companionship had only served to show her more of the Englishwoman's lovable temperament. They all loved her at the Gaard. Her presence was a joy to them; and she passed amongst them as one of those privileged beings for whom barriers are broken down and bridges are built, so that she might go her way at her own pleasure into people's hearts and minds. Yes, Knutty turned to her with hope and belief. And as she was saying to herself that Katharine was the one person in the world to help that lonely man and desolate boy, to build her bridge to reach the man, and her bridge to reach the boy, and a third bridge for the man and the boy to reach each other – as she was saying all this, with never one single jealous thought, there came a soft knock at her door. She did not notice it at first; but she heard it a few seconds later, and when she opened her door, Katharine was standing there.

"My dear," Knutty exclaimed, and she led her visitor into the room.

"I have been uneasy about you," Katharine said, "and could not get to sleep. I felt I must come and see if anything were wrong with you. Why, you haven't been to bed yet. Do you know it is two o'clock?"

"It might be any time in a Norwegian summer night, and I've been busy thinking," said Knutty – "thinking of you, and longing for the morrow to come when I might tell you of some trouble which lies heavy on my heart."

"Most curious," said Katharine. "I had a strong feeling that you wanted me. I thought I heard you calling me."

"I did call you," Knutty said, "none the less loudly because voicelessly. I wanted to tell you that Mrs Stanhope did see Alan before he left England. Your warning to my poor Clifford came too late. She took the boy and made him drink of the poison of disbelief."

Then she gave Katharine an account of her painful interview with Alan. Katharine had previously told Knutty a few particulars of her own encounter with Mrs Stanhope at the Tonedales, and she now, at Knutty's request, repeated the story, adding more details in answer to the old Dane's questionings. Long and anxiously these two new friends, who were learning to regard each other as old friends, discussed the situation.

"I cannot bear that the boy should be suffering in this way," Knutty said. "And I cannot bear that my poor Clifford should know. For he has come back happier – ah, you know something about that, my dear. And I am glad enough to see even the beginning of a change in him. Only it is pathetic that he, without knowing it, should be steering for some happiness in a distant harbour, whilst the boy should be drifting out to sea – alone."

"He shall not drift out to sea," Katharine said. "He must and shall believe in his father again."

"But, my dear, how are you going to manage that?" Knutty asked sadly.

"By my own belief," Katharine answered simply.

"You believe in him?" Knutty said, half to herself.

"Absolutely," Katharine answered, with a proud smile on her face.

"How you comfort me!" said Knutty. "Here have I been wrestling with plans and problems until all my intelligence had gone – all of it except the very best bit of it which called out to you for help. And you come and give me courage at once, not because you have any plans, but because you are yourself."

They were standing together by the window, and Katharine put her arm through Knutty's. They looked a strange pair: Knutty with her unwieldy presence of uncompromising bulk, and Katharine with her own special grace of build and bearing. She was clothed in a blue dressing-gown. Her luxuriant hair fell down far below her waist. The weird Norwegian moon streamed into the room, and shone caressingly around her. It was a wonderful night: without the darkness of the south and without the brightness of the extreme north; a night full of strange half-lights and curious changes. At one moment dark-blue clouds hung over the great valley, mingling with the mists in fantastic fashion. Then the blue clouds would give place to others, rosy-toned or sombre grey, and these two would mingle with the mists. Then the next moment the moon would reassert herself, and her rays would light up the rivers and fill the mists with diamonds. Then there would come a moment when mists and clouds were entirely separated; and between this gap would be seen, as in a dream, a vision of the valley beyond, mysterious and haunting. Verily a land of sombre wonder and mystic charm, this great Gudbrandsdal of Norway, with its legends of mortal and spirit, fit scene for weird happenings and strange beliefs, being a part of that whole wonderful North, the voice of which calls aloud to some of us, and which, once heard, can never be lulled into silence.

The two women stood silently watching the beauty of this Norwegian summer night, arrested in their own personal feelings by Nature's magnetism.

"Behold!" cries Nature, and for the moment we are hers and hers only. Then she releases us, and we turn back to our ordinary life conscious of added strength and richness.

Katharine turned impetuously to Knutty.

"He must and shall believe in his father again," she said. "I know how helpless boys are in their troubles, and how unreachable. But we will reach him – you and I."

"With you as ally," said Knutty, "I believe we could do anything."

"Poor little fellow, poor little fellow!" said Katharine tenderly.

As she spoke she glanced out of the window and saw some one coming down from the birch-woods. She watched the figure approaching nearer and nearer to the Gaard.

"There is some one coming down from the woods," she said. "How distinctly one can see in this strange half-light!"

"One of the cotters, perhaps," suggested Knutty.

"No," said Katharine, "it is the boy – it's Alan."

They watched him, with tears of sympathy in their eyes. They knew by instinct that he had been wandering over the hills, fretting his young heart out. They drew back, so that he might not see them as he passed up the garden.

They heard him go into the back verandah and up the outer stairs leading to his room.

They caught sight of his troubled face.

CHAPTER IX

It was Katharine who proposed the expedition to a group of Saeters. She came down one morning in a determined frame of mind, and no obstacles could deter her from carrying out her scheme. F – was about a day's journey distant from the Gaard, and Katharine had heard of its beauties from several of the guests, including the Sorenskriver. The difficulty was to get horses at the Gaard, for they were wanted in the fields, and when not required for work, they appeared to be wanted for rest. Solli did not like his horses to go for expeditions, and as a rule he was not to be persuaded to change his views. When asked, he always answered:

"The horses cannot go." And there the matter ended.

To-day also he said, "The horses cannot go;" and Katharine, understanding that entreaty was vain, made no sign of disappointment, and determined to walk. She invited Alan specially to come with her, and the boy, in his shy way, was delighted. Her manner to him was so genial that, spite of his trouble, he cheered up.

"The others may come with us if they like," she said to him; "but we are the leaders of this expedition. It is true that we don't know the way; but born leaders find the way, don't they?"

Ejnar declared he would go, and Gerda, still feeling injured, said she would stay behind. But Tante advised her to go and see that Ejnar did not run away with Katharine. The Sorenskriver refused rather sulkily, but was found on the way afterwards, having changed his mind and discovered a short cut. The little Swedish lady-artist accepted gladly, and the Swedish professor accompanied her as a matter of course, being always in close attendance on his pretty young compatriot. Clifford said he would remain with Knutty, but Knutty said:

"Many thanks. But I'm coming too. Do you suppose I've come to Norway to let others see Saeters? Not I."

"But, Knutty," he said, looking gravely at her, "you know we'd love to have you, but – "

"But you think it is not humanly possible," she answered, with a twinkle in her eye. "Well, I agree with you. If I walked, I should die; and if I rode, the horse would die! And as there is no horse – "

But just then Jens came into the courtyard leading Svarten, the black Gudbrandsdal horse, and Blakken, a sturdy little Nordfjording.12 Jens hitched Svarten to the gig. Another pony was brought from the field hard by.

"The horses can go," said Solli, looking rather pleased with himself; and the little band of travellers, agreeably surprised, called out:

"Tusend tak, Solli!"

"Well, now, there are horses," Clifford said, turning to Knutty.

"Kjaere," she answered, "I may be a wicked old wretch, but I'm not as bad as that yet! I'll stay at home and read to Bedstemor out of the old Bible which Bedstefar bought in exchange for a black cow! Could anything be more exciting? But you go – and be happy."

"Happiness is not for me, Knutty," he said.

"No, probably not," she answered gravely. "But go and pretend. There's no harm in that."

"All the same," he said a little eagerly, "it is curious how much brighter and happier I do feel since we came here. It's the getting back to you, Knutty. That is what it is."

"Yes, I can quite believe that," replied Knutty. "There now. They are starting off."

But he still lingered in the porch.

"What sort of nonsense have you been telling Miss Frensham about my researches?" he said, smiling shyly.

"Oh," said Knutty, "I only told her you were engaged on some ridiculous stereo-something investigations. I didn't think it was anything against your moral character."

He still lingered.

"Do you know," he said, "I've been thinking that I shall enlarge my laboratory when I get back. I believe I am going to do a lot of good new work, Knutty."

"I shouldn't wonder," she answered. "A man isn't done for at forty-three."

"No, that's just it," he said brightly. "Well, goodbye for the present."

She watched him hasten after the others. She laughed a little, and congratulated herself on her beautiful discretion. And then she went over to Bedstemor's, and on her way met old Kari carrying a bundle of wood. Old Kari, who always plunged without preliminaries into a conversation, said:

"Perhaps that nice Englishwoman will find a husband here after all, poor thing. Perhaps the Englishman will marry her. What dost thou think?"

Meanwhile Clifford hurried after the Saeter pilgrims, and caught up with Gerda and Ejnar. Katharine and Alan were on in front, but he did not attempt to join them. But he heard Alan laugh, and he was glad. A great gladness seized him as he walked on and on. She was there. That was enough for him. Ah, how he had thought of her when he was away. She did not know. No one knew. It was his own secret. No one could guess even. No one would ever know that Alan's unhappiness was only one of the reasons for their sudden return. There was another reason too: his own unconquerable yearning to see her. He had tried to conquer it; and he had not tried to conquer it. He had tried to ignore it; and he had not tried to ignore it. He had said hundreds of times to himself, "I am not free to love her;" and he had said hundreds of times too, "I am free to love her." He had said of her, "She is kind and pitiful; but she would never love me – a broken-spirited man – never – never." And he had said, "She loves me." He had said, "No, no, not for me the joys of life and love – not for me. But if only in earlier days – if only – " And he had said, "The past is gone, and the future is before me. Why must I turn from love and life?"

But he had ended with, "No, no, it is a selfish dream; there is nothing in me worthy of her – nothing for me to offer her – nothing except failure and a saddened spirit."

But this morning Clifford was not saying or thinking that. He remembered only that she was there – and the world was beautiful. For the moment, all troubles were in abeyance. He scarcely remembered that the boy shirked being with him and went his own way in proud reserve. He had, indeed, scarcely noticed it since his return. If Alan went off with Jens, it was only natural that the two lads should wish to be together. And for the rest, the rest would come right in time. So he strode on, full of life and vigour, and with a smile on his grave face. And Gerda said:

"And why do you smile, Professor?"

He answered:

"The world is beautiful, Frue.13 And the air is so crisp and fine."

Gerda, who enjoyed being with Knutty's Englishman, was glad that Ejnar was lingering behind picking some flower which had arrested his attention. She did not mind how far he lingered behind alone. It was the going on in front with Katharine which she wished to prevent! She said to Clifford:

"Your countrywoman is very attractive. I like her immensely. Do you like her?"

"Yes," said Clifford.

"She is not fond of chemistry, I think."

"No."

"Nor is she botanical."

"No," said Clifford.

"Nevertheless, she has a great charm," said Gerda. "Tante calls it temperamental charm. It must be delightful to have that mysterious gift. For it is a gift, and it is mysterious."

Clifford was silent. Gerda thought he was not interested in the Englishwoman.

"How blind he is!" she thought. "Even my Ejnar uses his eyes better. He knows that woman is charming."

Katharine was indeed charming that morning, and to every one. She had put little Fröken Eriksen, the Swedish artist, and the Swedish mathematical Professor, Herr Lindstedt, into the gig, so that they might enjoy a comfortable flirtation together. They laughed and greeted her pleasantly as they drove on in front.

"Tack!" they said, turning round and waving to her. They felt she understood so well.

Soon afterwards the Sorenskriver was found sitting on one of the great blocks of stone which formed the railing of the steep road down from the Solli Gaard.

"Good-morning," he said. "May a disagreeable old Norwegian join this party of nations?"

Katharine beamed on him, and spoke the one Norwegian word of which she was sure, "Velkommen!"

But she did not let him displace Alan. She kept the boy by her side, giving him the best of her kindness and brightness. She drew him out, heard something about his American journey, and listened to a long description of the ship which took him out and brought him home. He did not once speak of his father. And she did not speak of him. But she had a strong belief that if she could only manage to win the boy for herself, she could hand him back to his father and say, "Here is your boy. He is yours again. I have won him for you."

It was a joy to her to feel that she was working for Clifford Thornton. And with the pitiful tenderness that was her own birthright, she was glad that she was trying to help the boy. She knew she would succeed. No thoughts of failure crossed her mind. No fears of that poor Marianne possessed her. She made no plans, and reckoned on no contingencies. She had never been afraid of life. That was all she knew. And without realising it, she had a remarkable equipment for success in her self-imposed task. By instinct, by revelation, by reason of her big, generous nature, she understood Marianne: that poor Marianne, who, so she said to Knutty, could not be called unmerciful if she was ignorant – since mercy belonged only to true knowledge.

So she kept Alan by her side, and he was proud to be her chosen companion. She said:

"This is our show, you know. The other people are merely here on sufferance. And if the Sorenskriver says anything disagreeable about England, we'll wollop him and leave him tied up to a tree until we return."

"Or shove him down into the torrent," said Alan, delighted. "Here it is, just handy."

"Yes; but he has not begun yet," she answered. "We must give the poor man a chance."

"Don't you feel beastly angry when these foreigners say anything against England?" he asked.

"Beastly angry!" she replied with gusto.

He smiled with quiet satisfaction. He loved her comradeship of words as well as her comradeship of thoughts.

They passed over the bridge leading to the other side of the Vinstra gorge, stopped to rest at the Landhandleri (store-shop), and then began their long ascent to the Saeters. Up they went past several fine old farms; and as they mounted higher, they could see the Solli Gaard perched on the opposite ridge. The road was a rough carriage-road leading up to a large sanatorium, which was situated about three-quarters of the way to F – . As they mounted, the forest of Scotch firs and spruces seemed thicker and darker, being unrelieved by the presence of other trees, as in the valley below. Leafy mosses formed the carpeting of the forest, and a wealth of bilberries was accumulated in the spruce-woods; whilst the red whortleberry showed itself farther on in open dry spots amongst the pines which crept up higher than the Scotch firs – "Grantraeer," as the Norwegians call them. Then they, in their turn, thinned out, and the lovely birches began to predominate; so that the way through the forest became less gloomy, and the spirits of the pilgrims rose immediately, and Gerda sang. But, being Danish, she sang a song in praise of her native beech-woods! And the Sorenskriver joined in too, out of compliment to Denmark, but said that he would like to recite to the English people the poem about the beeches of Denmark, the birches of Sweden, and the fir-trees of Norway. The beeches were as the Danes themselves, comfortable, easy; the birches were even as the Swedes, graceful, gracious, light-hearted; and the grim firs were as the Norwegians, gloomy, self-contained, and sad.

"Therefore, Fröken," he said, turning to Katharine, "judge us gently. We are even as our country itself, stern and uncompromising."