полная версия

полная версияKatharine Frensham: A Novel

"Don't be with him. It is only an aberration. It won't do you or him any harm. He will soon be ready to quarrel with you over the Romney poppy. And you cannot possibly be angry with her. She knows nothing about it. Every one likes her; she wins every one. It is her nature; her temperament; her aura. If she has won the Sorenskriver, she could win the most ferocious Trold ever heard of in Norwegian lore. Don't be angry with anybody. I think I ought to be the one to be angry. He always interrupts our conversations. And you always want her when you can get her. Everybody wants her. Even Bedstemor likes to talk with her. I can scarcely get a word in. Poor old Tante."

"You wicked old woman, you were talking to her for hours yesterday," said Gerda, laughing.

"Nå," said Tante, "yesterday is not to-day."

"I cannot think what you want to talk to her about," said Gerda.

"There are other subjects besides the 'botanik,'" remarked Tante sternly.

"And, after all, you are both strangers," said Gerda.

"Strangers very often have a great deal to say to each other," answered Tante. "Ah, and here she comes. Now I insist on you dragging your wretched Ejnar off to your study and keeping him there. Have a quarrel. I mean a real botanical quarrel. Do, kjaere. You have not had one for quite two days. Talk about Salix. That is always a safe subject for a quarrel. And you need not be afraid that I will bore the barbarian woman. I will speak only of subjects which interest her."

No, Katharine was not bored. She drifted to Tante on every possible occasion; and they spoke on many different subjects, but always ended with Clifford Thornton. It was curious how he came into everything. If they began about the customs of the peasants, they finished up with Clifford and his boy. If they started off with Bedstefar's illness, which was becoming more and more serious, they ended with Clifford Thornton. If they spoke of England, it was natural enough that they should speak of Tante's Englishman. If they spoke of America, it was natural enough that Clifford and his boy should slip into the conversation. And if they spoke of Scandinavia, and especially of little Denmark, where he and his boy would soon be arriving, it was natural enough to refer to the two travellers now on their way home to Europe.

"Ja, ja," said Tante, "he always loved the North. I, who taught him, took care about that. And his father before him had loved the North. That was why I was chosen to be the little lad's governess; because I was a Dane – and not a bad-looking one either in those days, let me tell you! Yes, I was chosen out of about ten Englishwomen. I shall never forget that day."

"Tell me about it," Katharine said eagerly; and the old Danish woman, nothing loth, put down her knitting and gazed dreamily out on the great valley below. It was about six in the afternoon. All the other guests had finished their coffee and left the balcony, and Katharine and Tante were in sole possession. There were no sounds except the never-ceasing roar of the foss in the Vinstra Valley.

"It was many years ago," Tante said, – "about thirty eight, I think. He was seven years old when I was called to look after him. I journeyed to a desolate house in the country, in Surrey, and waited in a dismal drawing-room with several other ladies, who were all on the same errand. A tall, stern-looking man came into the room, greeted us courteously, but scanned us closely. And then he said, 'And which is the Danish lady?' And I said, 'I am the Dane.' And he said, 'Do you speak English very badly?' And I said, 'No, I speak it remarkably well.' And he smiled and said, 'Ah, you're a true Dane, I see. You have a good opinion of your powers.' And I said, 'Yes, of course I have.' Then I went with him alone into his study, another depressing room, and we had an interview of about an hour. I saw he loved the North. It was a passion with him. He was a lonely impersonal sort of creature; but his face lit up when he spoke of the North. He asked me to wait whilst he spoke with the other ladies. Lunch was served in the dining-room; and those of us who were not being interviewed, tried to enjoy an excellent meal. But every one was anxious, for the salary was exceptionally high, indeed princely. When all the interviewing was over, he did a curious thing; but I thought it considerate and kind to the little person for whose care he was providing. He went upstairs and brought down to us a desolate-looking little boy, and said:

"'Clifford, my little son, one of these ladies is going to be good enough to come and take care of you. I wonder which is the one you would like best of all.'

"The little fellow shrank back, for he was evidently shy; but he looked up into his father's stern face, and knew that he had to make an answer. Then very shyly he glanced round, and his eye rested on me.

"'That one, father,' he said, almost in a whisper.

"So that was how I came to be his governess. He knew what he wanted when he chose me. I have always wished that he could have known just as cleverly what he wanted when he chose his wife – that poor Marianne."

And here Tante paused, and gave that sort of pious regulation-sigh which we are always supposed to offer to the memory of all dead people, good, bad, or indifferent.

Katharine waited impatiently. She longed to know something about that dead wife. She longed to know something of Clifford's childhood, of his youth, his early career – but chiefly of that dead wife: whether he had loved her, whether she had loved him. She did not try to conceal her eagerness. She bent forward and touched Tante's hands.

"Tell me about her," she said. "I have only heard what Mrs Stanhope said of her."

"Ah," said Knutty, "she was her friend. If you have only heard what Mrs Stanhope said, you have heard only unjust things about my Clifford."

"Yes," replied Katharine, "and believed them to be impossible, and told her so."

"My dear," said Knutty warmly, "you have a mind that understands. Well, about this Marianne. She has gone her way, and I suppose custom demands that one should speak of her respectfully. But I cannot help saying that she had a Billingsgate temperament. That was the whole trouble. She had a great deal of beauty, and something of a heart. Indeed, she was not bad-hearted. I always wished she had been a downright devil; for then my poor Clifford would have known how to decide on a definite course of action. I own that I often wished she would run away with another man. But of course he would have forgiven her. Bah! It was so like her not to run away. Excuse me, my dear. But I have never learnt not to be impatient, even with her memory; for she preyed on his kindness and his great sense of chivalry. I don't know where she originally came from, and whether it was her original entourage which gave her the Billingsgate temperament, or whether it was just her natural possession independent of surroundings. I did not see her until he had married her. When I saw her, I knew of course that it was her physical charm with which he had fallen in love. It could not have been her mind. She had none."

Knutty paused a moment, took off her spectacles to clean them, and then continued:

"He married her in Berlin, and took her to Aberystwith College, where he was Professor of Chemistry for two years. Alan was born there. Then his father died and he gave up teaching. He settled down at 'Falun,' his country-house, and devoted himself to research-work: as far as she would let him. But she was jealous of his work, and I believe did her best to thwart it. I saw that as the time went on. He used to come over to Denmark partly to see me, and partly on his way to Sweden, which is a grand hunting-ground for mineralogists. He had always been interested in mineralogy; indeed, as a child he played with minerals as most children play with soldiers. Well, one morning he walked into my room unexpectedly and said, 'Knutty, I came to tell you I've discovered a new mineral. You know I've had a lot of disappointments over them; but this one has not cheated me. He is a new fellow beyond all doubt. And I felt I must have some one to be glad with me.' That was all he said; but there was something so pathetic about his obvious need of sympathy that I felt sure things were not going well with him at home. When I went over to stay with them, I understood. I had not been three days at 'Falun' before I discovered that Marianne had this unfortunate temperament, the very worst in the world for his peculiar sensitiveness and his curiously delicate brain. I knew his brain well. As a child, if not harassed, he could do wonders at his studies. But he needed an atmosphere of peace, in which to use his mental machinery successfully. I learnt to know this, and I gave him peace, dear little chap, and spared him most of the petty tyrannies which the grown-up impose on youngsters. But Marianne could give him no peace. Peace was not in her; nor did she wish for it; nor could she understand that any one wished for it. Life to her meant scenes: scenes over anything and everything. Day after day I saw the delicate balance of his brain, so necessary for the success of his investigations, cruelly disturbed. But to be just to Marianne, she did not know. And if she had been told, she would not have understood. I tried to hint at it once or twice; and I might as well have spoken in the Timbuctoo original dialect. I did not even offend her. She did not even understand that much of this foreign language. It was all hopeless. Her aura was impossible. So I said 'Farvel,' and I never went to stay with them again for any length of time. But occasionally I went for a day or two to please him. I saw as time went on, that he was getting some comfort out of the boy. That was a comfort to me. But I also saw that the brilliant promises of his early manhood were being unfulfilled. I heard that his scientific friends wondered and mourned. They did not know the disadvantages with which he had to cope. Probably they would not have allowed themselves to be thus harassed. But he was not they, and they were not he. And, after all, a man can only be himself. And if he is born with a heart as well as a brain, and with an almost excessive chivalry for the feelings of other people, then he is terribly at the mercy of his surroundings.

"Yes," she repeated, "at the mercy of his surroundings. And poor Marianne had no mercy on him: none."

"But if she had no understanding, then it was not that she was unmerciful, but only ignorant," Katharine said gently.

"Yes, yes; but it works out the same," Tante answered.

"Not quite," Katharine replied. "It makes one think more mercifully of her."

"Why, that is precisely the sort of thing he says!" Knutty exclaimed.

"Is it?" said Katharine, flushing up to her very eyes. And at that moment there came a sound of sweet melancholy music from the hillside.

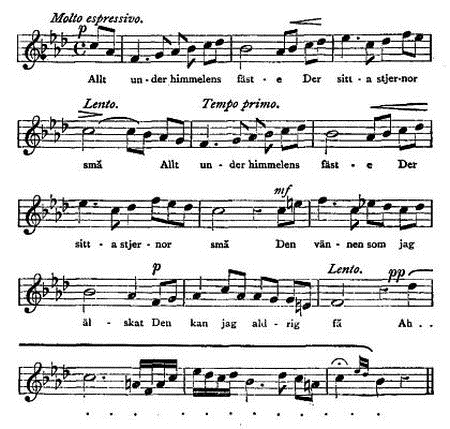

"That is Gerda," whispered Tante. "That is one of her favourite Swedish songs – how sweet and melancholy it is."

They listened, arrested and entranced. The stillness of the evening and the pureness of the air made a silent accompaniment to Gerda's beautiful voice.

And the wail of despair at the end of the verse was almost heartrending.

They listened until the sad strains had died away, and then Tante softly translated the words:

"High on the dome of heaven shine the bright stars;The lover whom I love so well, I shall reach him never.Ah me, ah me!.."She turned impulsively to Katharine.

"But that is not for you, not for you," she said. "You will reach him, I know you will reach him – I feel it. I want you to reach him – something or other tells me that it must and will be so – that – "

The door of the balcony opened hastily, and Ragnhild came to Tante and held out both her hands to help her up.

"Two Englishmen have come and are asking for thee," she said.

"Men du milde Himmel!"10 cried Tante. "My icebergs, of course!"

She almost ran to the hall, where she found Clifford and Alan standing together like the two forlorn creatures that they were.

"Velkommen, velkommen!" she cried. "I don't know where you've come from, whether from the bottom of the sea or the top of the air! Nor how you've got here! But velkommen, velkommen!"

Their faces brightened up when they saw her and heard her cheery voice with its slight foreign accent.

"Oh, Knutty, it is good to see you again," the man said.

"Yes, by Jove! it is ripping," the boy said.

"Come out into the balcony, dear ones," she said, taking them by the hand as she would have taken two children. "And I'll inquire about your rooms and your food. You look like tired and hungry ghosts."

Katharine was bending over the balcony, looking down fixedly at those wonderful rivers, and with the sound and words of that sad song echoing in her ears and heart. Then she turned round and saw them both; saw the look of shy pleasure on the boy's face, and of gladness on the man's. The music died away, hushed by the gladness of her own heart.

"Velkommen!" she said, coming forward to greet them. "I've learnt that much Norwegian, you see!"

CHAPTER VII

Knutty was overjoyed at the return of her icebergs, and it was pathetic to see how glad they were to be with her again. She thought that, on the whole, they were the better for their journey; but when she questioned Clifford, he told her that Alan had not cared to be with him.

"He is much happier since he has returned and is not alone with me," Clifford said.

"And you?" asked Knutty.

"I am much happier too, Knutty," he said thoughtfully.

And he looked in the direction of the foss, where Katharine had just gone with the Sorenskriver.

"Ah," said Knutty, "you are a strange pair, you and your boy."

He made no reply; but afterwards said in an absent sort of way:

"I think I will take a stroll in the direction of the foss."

"Yes, I should, if I were you," said Knutty, with a twinkle in her eye. "The Sorenskriver will be so pleased to see you, I'm sure."

He glanced at her a little suspiciously, but saw only a grave, preoccupied expression on her naughty old face.

But when he had gone, she laughed to herself and said:

"Yes, there is decidedly daylight, not through a leper's squint, but through a rose-window! Only I must be careful not to turn it into black darkness again. I must see nothing and hear nothing, and I must talk frequently of Marianne – or oughtn't I to talk of her? Nå, I wonder which would be the best plan. If I do speak of her, it will encourage him to remember her; and if I don't speak of her it will encourage him to brood over her in silence. She always was a difficulty, and always will be until – And even then, there's the other iceberg to deal with – ah, and here he comes – made friends with Jens, I see, and no difficulty about the language – Jens never speaking a word, and Alan only saying something occasionally, like his father."

The two boys parted at the Stabur, where Ragnhild was standing on the steps holding a pile of freshly made Fladbröd. Alan looked up at her, took off his little round cricketing-cap, blushed, made his way over to the porch, and sat down by Knutty. And Ragnhild thought:

"That nice English boy. He shall have plenty of multebaer."

So she disappeared into the Stabur and brought out a plateful of multebaer, which she handed him with a friendly nod. He fell to without any hesitation, and Knutty watched him and smiled.

"Well, kjaere," she said, "and what do you think of this part of the world? Glad to be here?"

"Yes, Knutty," he answered. "And it is ripping to see you again."

"Am I so very 'bully'?" she said, in her teasing way.

"Yes," he said, smiling.

"Ah," she said, "I suppose I am!" And they both laughed.

"Jens and I are going fishing this afternoon up to a mountain lake over there," he said. "I wish you'd come too. Do, Knutty."

"Dear one," she answered, "I'll come with pleasure if you'll send over for one of the London cart-horses. Nothing else on this earth could carry me, and then I suppose he couldn't climb! You surely did not think of hoisting me up on one of those yellow ponies? No, I think I'll stop below and eat the fish you bring home. All the same, thank you for the invitation. Many regrets that age and weight, specially weight, prevent me from accepting."

There was a pause, and Alan went on eating his multebaer.

"Did you like your journey to America?" she asked, without looking up from her work.

"Yes," he answered half-heartedly, and his face clouded over. "But – but I was glad to come back."

"Well," she said, "that is what many people say. The New World may be good enough in its way, but the Old World is the Old World, when all is said and done. And you got tired of the Americans, did you?"

"Oh no," he said, "it wasn't that. But – "

He hesitated, and then he blurted out:

"I wish you'd been with us, Knutty. It would have been so different then."

"Nei, stakkar," she said. "You'll make old Knutty too conceited if you go on saying these nice things to her."

He had put down his plate of multebaer, and was now fiddling nervously with a Swedish knife that Knutty had given him. Knutty glanced at him with her sly little old eyes. She knew she was in for confidences if she conducted herself with discretion.

"Give it to me," she said, holding out her hand for the knife. "This is the way it opens – so – and then you stick it through the case – so – and then it's ready to stick anybody you don't like – so – in true Swedish fashion, with which I have great sympathy – there it is!"

The boy went on fiddling with the knife, and then he took his cap off and fiddled with that.

"Du milde Himmel!" thought Knutty. "These icebergs! Why do I ever put up with them?"

"Knutty," the boy began nervously, "I want so dreadfully to ask you something – about – mother. Was she – very unhappy – do you think? I can't get out of my head what Mrs Stanhope said. I tried to forget it – but – "

He looked up hopelessly at Knutty, and broke off.

Knutty gave no sign.

"Twice I nearly ran away from father," the boy went on. "I – I wanted to be alone – not with father – once at New York – and another time at Chicago. There were two fellows going out West from there, and – I wanted to be alone, not with father – and I thought I could get along somehow – other fellows do – and then I remembered how you said that he only had me – and I stayed – but – "

He looked up again at Knutty, and this time she answered:

"I know," she said. "I understand."

"You don't think it beastly of me?" he said.

"No," she said, "not beastly at all; only very, very sad."

"You won't let father know I – I nearly left him?" Alan asked.

"No; you may rely on me," she answered gently. And she knew that she was speaking the truth, and that she would have no heart to tell Clifford. With her quick insight she saw the whole thing in a flash of light. She guessed that Mrs Stanhope had got hold of the boy, and planted in his heart some evil seed which had grown and grown. The difficulty was to find out exactly what she had said to him; and Knutty knew that Alan would be able to tell her only unconsciously, as it were, involuntarily. Her kind old heart bled for the lad when she thought how much he must have suffered, alone and unhelped. His simple words about wanting to get away from his father spoke volumes in themselves. And he seemed to harp on this, for he said almost at once:

"You see, I shall be going back to school, and then to college, and then to work."

"And then out into the world to make your name as a great architect," she said.

He smiled a ghost of a smile.

"Yes," he said; "but far away, Knutty, out in the colonies somewhere."

"Alan," she said suddenly, "you asked me about your mother – whether I thought she had been unhappy. I don't know; I never knew her well enough to be able to say. I thought she seemed happy when I saw her last – about two years ago, I think – and she was looking very beautiful. She was a beautiful woman your mother, and well set-up, too, wasn't she?"

"Yes," she boy said, and his lip quivered. He turned away and leaned against the pillar of the porch.

"Oh, Knutty," he said, turning round to her impetuously, "why did she die? Why isn't she here? There wasn't any need for her to die. She never would have died if father had been kinder to her, if we'd both been kinder to her; but – she was unhappy. Mrs Stanhope said she was unhappy: she told me all about it before we left England. I can't forget what she said – what she said about – about father being the cause of mother's death; that's what she meant – I know that's what she meant… I can't get it out of my head. I never thought of it like that until she told me; but when she spoke as she did, then I knew all at once that – that – that there was something wrong somewhere about mother's death, and that I oughtn't to forget it, being her son – and – and she was fond of me – and – "

He broke off. Knutty had risen, and put her hand on the boy's shoulder.

"Kjaere," she said in a strained voice, "I did not know things were as bad as this with you. My poor boy."

She slipped her arm through the boy's arm and led him away from the courtyard, down past the cowhouse and the hay-barns and through the white gate.

Old Kari was grubbing about, singing her favourite refrain to call the cows back: —

"Sulla ma, Sulla ma, Sulla ma, aa kjy!Sulla ma, Sulla ma, Sulla ma, aa kjy!11Sullam, sullam, sy-y-y y-y-y!"Bedstemor was in her garden, giving an eye to her red-currant bushes, of which she was specially proud, and casting a sly glance round to see what the Swedish artist-lady was doing perched on that rock in the next field. She was only looking towards the Gaard and measuring the cowhouse in the air. Bedstemor thought there was no harm in that; and any way, these people had to do something.

The Sorenskriver was coming down from the birch-woods, alone and apparently in a disagreeable mood, for he pushed roughly on one side the little golden-haired daughter of one of the cotters who was playing on the hillside.

"These wretched Englishmen," he said, frowning. "Uff, they are always in the way, all over the world. And I was having such a pleasant time with her before this fellow came."

Katharine and Clifford were lingering near the foss. Katharine was making a little water-colour of the lovely scene. Through the trees one could catch a glimpse of the shining river and a bit of the bright blue sky.

"Yes," Clifford was saying, "my old Dane was wise to send us, and we were wise to come back. We were not happy together, Miss Frensham. But since we have returned the boy is happier, and – I am happier too."

Katharine, bending over her work, whispered to herself:

"And I – I am happier too."

But down by Knutty's mountain-ashes, near the black hay-barn, an old woman and a young boy sat, with pale, drawn faces.

CHAPTER VIII

Gerda had pretended to hope that when Tante's English friends arrived on the scene, she would mend her strange ways, and no longer haunt the cowhouse and seek the companionship of old Kari and of Thea, who was so clever at making Fladbröd, and Mette, who had three fatherless babies and a dauntless demeanour which seemed to be particularly attractive to wicked old Knutty. But Tante was incorrigible, and would not for any one's sake have missed her evening visit to that august building. So after her sad talk with Alan, she stood and waited as usual, whilst Mette, that bright gay soul, called the cows down to the Gaard.

"Kom da, stakkar, kom da, stakkar!" ("Come then, my poor little dears!"), she cried merrily.

And Gulkind (yellow cheek), Brungaas (brown goose), Blomros (red rose), and Fjeldros (mountain rose) responded with varying degrees of bellowing and dilatoriness.

When they were safely in their stalls, the singing began. Thea had the softest voice, but Mette had a dramatic delivery. Old Kari acted as prompter when they forgot the words of the old folk-songs, and the cows went on munching steadily and switching their tails in the singers' faces, so that the music was mingled with strange discords of scolding and Knutty's laughter. And then Mette got up, and began to dance some old peasant-dance; and very pretty and graceful she looked, too, in her old cow-dress and torn bodice.