полная версия

полная версияHow to Camp Out

Bathing is not recommended while upon the march, if one is fatigued or has much farther to go. This seems to be good counsel, but I do advise a good scrubbing near the close of the day; and most people will get relief by frequently washing the face, hands, neck, arms, and breast, when dusty or heated, although this is one of the things we used to hear cried down in the army as hurtful. It probably is so to some people: if it hurts you, quit it.

FOOT-SORENESS AND CHAFING

After you have marched one day in the sun, your face, neck, and hands will be sunburnt, your feet sore, perhaps blistered, your limbs may be chafed; and when you wake up on the morning of the second day, after an almost sleepless night, you will feel as if you had been "dragged through seven cities."

I am not aware that there is any preventive of sunburn for skins that are tender. A hat is better to wear than a cap, but you will burn under either. Oil or salve on the exposed parts, applied before marching, will prevent some of the fire; and in a few days, if you keep in the open air all the time, it will cease to be annoying.

To prevent foot-soreness, which is really the greatest bodily trouble you will have to contend with, you must have good shoes as already advised. You must wash your feet at least once a day, and oftener if they feel the need of it. The great preventive of foot-soreness is to have the feet, toes, and ankles covered with oil, or, better still, salve or mutton-tallow; these seem to act as lubricators. Soap is better than nothing. You ask if these do not soil the stockings. Most certainly they do. Hence wash your stockings often, or the insides of the shoes will become foul. Whenever you discover the slightest tendency of the feet to grow sore or to heat, put on oil, salve, or soap, immediately.

People differ as to these things. To some a salve acts as an irritant: to others soap acts in the same way. You must know before starting—your mother can tell you if you don't know yourself—how oil, glycerine, salve, and soap will affect your skin. Remember, the main thing is to keep the feet clean and lubricated. Wet feet chafe and blister more quickly than dry.

The same rule applies to chafing upon any part of the body. Wash and anoint as tenderly as possible. If you have chafed in any part on previous marches, anoint it before you begin this.

When the soldiers found their pantaloons were chafing them, they would tie their handkerchiefs around their pantaloons, over the place affected, thus preventing friction, and stopping the evil; but this is not advisable for a permanent preventive. A bandage of cotton or linen over the injured part will serve the purpose better.

Another habit of the soldiers was that of tucking the bottom of the pantaloons into their stocking-legs when it was dusty or muddy, or when they were cold. This is something worth remembering. You will hardly walk a week without having occasion to try it.

Leather leggins, such as we read about in connection with Alpine travel, are recommended by those who have used them as good for all sorts of pedestrianism. They have not come into use much as yet in America.

The second day is usually the most fatiguing. As before stated, you suffer from loss of sleep (for few people can sleep much the first night in camp), you ache from unaccustomed work, smart from sunburn, and perhaps your stomach has gotten out of order. For these reasons, when one can choose his time, it is well to start on Friday, and so have Sunday come as a day of rest and healing; but this is not at all a necessity. If you do not try to do too much the first few days, it is likely that you will feel better on the third night than at any previous time.

I have just said that your stomach is liable to become disordered. You will be apt to have a great thirst and not much appetite the first and second days, followed by costiveness, lame stomach, and a feeling of weakness or exhaustion. As a preventive, eat laxative foods on those days,—figs are especially good,—and try not to work too hard. You should lay your plans so as not to have much to do nor far to go at first. Do not dose with medicines, nor take alcoholic stimulants. Physic and alcohol may give a temporary relief, but they will leave you in bad condition. And here let me say that there is little or no need of spirits in your party. You will find coffee or tea far better than alcohol.

Avoid all nonsensical waste of strength, and gymnastic feats, before and during the march; play no jokes upon your comrades, that will make their day's work more burdensome. Young people are very apt to forget these things.

Let each comrade finish his morning nap. A man cannot dispense with sleep, and it is cruel to rob a friend of what is almost his life and health. But, if any one of your party requires more sleep than the others, he ought to contrive to "turn in" earlier, and so rise with the company.

You have already been advised to take all the rest you can at the halts. Unsling the knapsack, or take off your pack (unless you lie down upon it), and make yourself as comfortable as you can. Avoid sitting in a draught of air, or wherever it chills you.

If you feel on the second morning as if you could never reach your journey's end, start off easily, and you will limber up after a while.

The great trouble with young people is, that they are ashamed to own their fatigue, and will not do any thing that looks like a confession. But these rules about resting, and "taking it easy," are the same in principle as those by which a horse is driven on a long journey; and it seems reasonable that young men should be favored as much as horses.

Try to be civil and gentlemanly to every one. You will find many who wish to make money out of you, especially around the summer hotels and boarding-houses. Avoid them if you can. Make your prices, where possible, before you engage.

Do not be saucy to the farmers, nor treat them as "country greenhorns." There is not a class of people in the country of more importance to you in your travels; and you are in honor bound to be respectful to them. Avoid stealing their apples, or disturbing any thing; and when you wish to camp near a house, or on cultivated land, obtain permission from the owner, and do not make any unreasonable request, such as asking to camp in a man's front-yard, or to make a fire in dry grass or within a hundred yards of his buildings. Do not ask him to wait on you without offering to pay him. Most farmers object to having people sleep on their hay-mows; and all who permit it will insist upon the rule, "No smoking allowed here." When you break camp in the morning, be sure to put out the fires wherever you are; and, if you have camped on cleared land, see that the fences and gates are as you found them, and do not leave a mass of rubbish behind for the farmer to clear up.

MOUNTAIN CLIMBING

When you climb a mountain, make up your mind for hard work, unless there is a carriage-road, or the mountain is low and of gentle ascent. If possible, make your plans so that you will not have to carry much up and down the steep parts. It is best to camp at the foot of the mountain, or a part way up, and, leaving the most of your baggage there, to take an early start next morning so as to go up and down the same day. This is not a necessity, however; but if you camp on the mountain-top you run more risk from cold, fog, (clouds), and showers, and you need a warmer camp and more clothing than down below.

Often there is no water near the top: therefore, to be on the safe side, it is best to carry a canteen. After wet weather, and early in the summer, you can often squeeze a little water from the moss that grows on mountain-tops.

It is so apt to be chilly, cloudy, or showery at the summit, that you should take a rubber blanket and some other article of clothing to put on if needed. Although a man may sometimes ascend a mountain, and stay on the top for hours, in his shirt-sleeves, it is never advisable to go so thinly clad; oftener there is need of an overcoat, while the air in the valley is uncomfortably warm.

Do not wear the extra clothing in ascending, but keep it to put on when you need it. This rule is general for all extra clothing: you will find it much better to carry than to wear it.

Remember that mountain-climbing is excessively fatiguing: hence go slowly, make short rests very often, eat nothing between meals, and drink sparingly.

There are few mountains that it is advisable for ladies to try to climb. Where there is a road, or the way is open and not too steep, they may attempt it; but to climb over loose rocks and through scrub-spruce for miles, is too difficult for them.

CHAPTER VIII

THE CAMP

It pays well to take some time to find a good spot for a camp. If you are only to stop one night, it matters not so much; but even then you should camp on a dry spot near wood and water, and where your horse, if you have one, can be well cared for. Look out for rotten trees that may fall; see that a sudden rain will not drown you out; and do not put your tent near the road, as it frightens horses.

For a permanent camp a good prospect is very desirable; yet I would not sacrifice all other things to this.

If you have to carry your baggage any distance by hand, you will find it convenient to use two poles (tent-poles will serve) as a hand-barrow upon which to pile and carry your stuff.

A floor to the tent is a luxury in which some indulge when in permanent camp. It is not a necessity, of course; but, in a tent occupied by ladies or children, it adds much to their comfort to have a few boards, an old door, or something of that sort, to step on when dressing. Boards or stepping-stones at the door of the tent partly prevent your bringing mud inside.

If you are on a hillside, pitch your tent so that when you sleep, if you are to sleep on the ground, your feet will be lower than your head: you will roll all night, and perhaps roll out of the tent if you lie across the line running down hill.

As soon as you have pitched your tent, stretch a stout line from the front pole to the back one, near the top, upon which to hang your clothes. You can tighten this line by pulling inwards the foot of one pole before tying the line, and then lifting it back.

Do not put your clothes and bedding upon the bare ground: they grow damp very quickly. See, too, that the food is where ants will not get at it.

Do not forget to take two or three candles, and replenish your stock if you burn them: they sometimes are a prime necessity. Also do not pack them where you cannot easily find them in the dark. In a permanent camp you may be tempted to use a lantern with oil, and perhaps you will like it better than candles; but, when moving about, the lantern-lamp and oil-can will give you trouble. If you have no candlestick handy, you can use your pocket-knife, putting one blade in the bottom or side of the candle, and another blade into the ground or tent-pole. You can quickly cut a candlestick out of a potato, or can drive four nails in a block of wood.

If your candles get crushed, or if you have no candles, but have grease without salt in it, you can easily make a "slut" by putting the grease in a small shallow pan or saucer with a piece of wicking or cotton rag, one end of which shall be in the grease, and the other, which you light, held out of it. This is a poor substitute for daylight, and I advise you to rise and retire early (or "turn in" and "turn out" if you prefer): you will then have more daylight than you need.

BEDS

Time used in making a bed is well spent. Never let yourself be persuaded that humps and hollows are good enough for a tired man. If you cut boughs, do not let large sticks go into the bed: only put in the smaller twigs and leaves. Try your bed before you "turn in," and see if it is comfortable. In a permanent camp you ought to take time enough to keep the bed soft; and I like best for this purpose to carry a mattress when I can, or to take a sack and fill it with straw, shavings, boughs, or what not. This makes a much better bed, and can be taken out daily to the air and sun. By this I avoid the clutter there always is inside a tent filled with boughs; and, more than all, the ground or floor does not mould in damp weather, from the accumulation of rubbish on it.

It is better to sleep off the ground if you can, especially if you are rheumatic. For this purpose build some sort of a platform ten inches or more high, that will do for a seat in daytime. You can make a sort of spring bottom affair if you can find the poles for it, and have a little ingenuity and patience; or you can more quickly drive four large stakes, and nail a framework to them, to which you can nail boards or barrel-staves.9 All this kind of work must be strong, or you can have no rough-and-tumble sport on it. We used to see in the army sometimes, a mattress with a bottom of rubber cloth, and a top of heavy drilling, with rather more cotton quilted10 between them than is put into a thick comforter. Such a mattress is a fine thing to carry in a wagon when you are on the march; but you can make a softer bed than this if you are in a permanent camp.

SLEEPING

"Turn in" early, so as to be up with the sun. You may be tempted to sleep in your clothes; but if you wish to know what luxury is, take them off as you do at home, and sleep in a sheet, having first taken a bath, or at least washed the feet and limbs. Not many care to do this, particularly if the evening air is chilly; but it is a comfort of no mean order.

If you are short of bedclothes, as when on the march, you can place over you the clothes you take off (see p. 19); but in that case it is still more necessary to have a good bed underneath.

You will always do well to cover the clothes you have taken off, or they will be quite damp in the morning.

See that you have plenty of air to breathe. It is not best to have a draught of air sweeping through the tent, but let a plenty of it come in at the feet of the sleeper or top of the tent.

A hammock is a good thing to have in a permanent camp, but do not try to swing it between two tent-poles: it needs a firmer support.

Stretch a clothes-line somewhere on your camp-ground, where neither you nor your visitors will run into it in the dark.

If your camp is where many visitors will come by carriage, you will find that it will pay you for your trouble to provide a hitching-post where the horses can stand safely. Fastening to guy-lines and tent-poles is dangerous.

SINKS

In a permanent camp you must be careful to deposit all refuse from the kitchen and table in a hole in the ground: otherwise your camp will be infested with flies, and the air will become polluted. These sink-holes may be small, and dug every day; or large, and partly filled every day or oftener by throwing earth over the deposits. If you wish for health and comfort, do not suffer a place to exist in your camp that will toll flies to it. The sinks should be some distance from your tents, and a dry spot of land is better than a wet one. Observe the same rule in regard to all excrementitious and urinary matter. On the march you can hardly do better than follow the Mosaic law (see Deuteronomy xxiii. 12, 13).

In permanent camp, or if you propose to stay anywhere more than three days, the crumbs from the table and the kitchen refuse should be carefully looked after: to this end it is well to avoid eating in the tents where you live. Swarms of flies will be attracted by a very little food.

A spade is better, all things considered, than a shovel, either in permanent camp or on the march.

HOW TO KEEP WARM

When a cold and wet spell of weather overtakes you, you will inquire, "How can we keep warm?" If you are where wood is very abundant, you can build a big fire ten or fifteen feet from the tent, and the heat will strike through the cloth. This is the poorest way, and if you have only shelter-tents your case is still more forlorn. But keep the fire a-going: you can make green wood burn through a pelting storm, but you must have a quantity of it—say six or eight large logs on at one time. You must look out for storms, and have some wood cut beforehand. If you have a stove with you, a little ingenuity will enable you to set it up inside a tent, and run the funnel through the door. But, unless your funnel is quite long, you will have to improvise one to carry the smoke away, for the eddies around the tent will make the stove smoke occasionally beyond all endurance. Since you will need but little fire to keep you warm, you can use a funnel made of boards, barrel-staves, old spout, and the like. Old tin cans, boot-legs, birch-bark, and stout paper can be made to do service as elbows, with the assistance of turf, grass-ropes, and large leaves. But I forewarn you there is not much fun, either in rigging your stove and funnel, or in sitting by it and waiting for the storm to blow it down. Still it is best to be busy.

Another way to keep warm is to dig a trench twelve to eighteen inches wide, and about two feet deep, running from inside to the outside of the tent. The inside end of the trench should be larger and deeper; here you build your fire. You cover the trench with flat rocks, and fill up the chinks with stones and turf; boards can be used after you have gone a few feet from the fireplace. Over the outer end, build some kind of a chimney of stones, boxes, boards, or barrels. The fireplace should not be near enough to the side of the tent to endanger it; and, the taller the chimney is, the better it will draw if you have made the trench of good width and air-tight. If you can find a sheet-iron covering for the fireplace, you will be fortunate; for the main difficulty in this heating-arrangement is to give it draught enough without letting out smoke, and this you cannot easily arrange with rocks. In digging your trench and fireplace, make them so that the rain shall not flood them.

FIREPLACE

If flat rocks and mud are plenty, you can perhaps build a fireplace at the door of your tent (outside, of course), and you will then have something both substantial and valuable. Fold one flap of the door as far back as you can, and build one side of the fireplace against the pole,11 and the other side against, or nearly over to, the corner of the tent. Use large rocks for the lower tiers, and try to have all three walls perpendicular and smooth inside. When up about three feet, or as high as the flap of the tent will allow without its being scorched, put on a large log of green wood for a mantle, or use an iron bar if you have one, and go on building the chimney. Do not narrow it much: the chimney should be as high as the top of the tent, or eddies of wind will blow down occasionally, and smoke you out. Barrels or boxes will do for the top, or you can make a cob-work of split sticks well daubed with mud. All the work of the fireplace and chimney must be made air-tight by filling the chinks with stones or chips and mud. When done, fold and confine the flap of the tent against the stonework and the mantle; better tie than nail, as iron rusts the cloth. Do not cut the tent either for this or any other purpose: you will regret it if you do. Keep water handy if there is much woodwork; and do not leave your tent for a long time, nor go to sleep with a big fire blazing.

If you have to bring much water into camp, remember that two pails carry about as easily as a single one, provided you have a hoop between to keep them away from your legs. To prevent the water from splashing, put something inside the pail, that will float, nearly as large as the top of the pail.

HUNTERS' CAMP

It is not worth while to say much about those hunters' camps which are built in the woods of stout poles, and covered with brush or the bark of trees: they are exceedingly simple in theory, and difficult in practice unless you are accustomed to using the axe. If you go into the woods without an axeman, you had better rely upon your tents, and not try to build a camp; for when done, unless there is much labor put in it, it is not so good as a shelter-tent. You can, however, cut a few poles for rafters, and throw the shelter-tent instead of the bark or brush over the poles. You have a much larger shelter by this arrangement of the tent than when it is pitched in the regular way, and there is the additional advantage of having a large front exposed to the fire which you will probably build; at the same time also the under side of the roof catches and reflects the heat downward. When you put up your tent in this way, however, you must look out not to scorch it, and to take especial care to prevent sparks from burning small holes in it. In fact, whenever you have a roaring fire you must guard against mischief from it.

Do not leave your clothes or blanket hanging near a brisk fire to dry, without confining them so that sudden gusts of wind shall not take them into the flame.

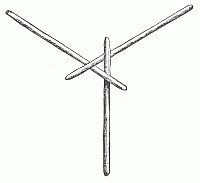

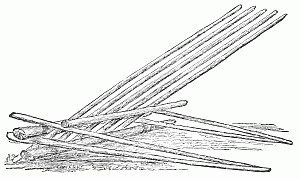

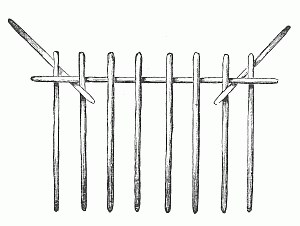

You may some time have occasion to make a shelter on a ledge or floor where you cannot drive a pin or nail. If you can get rails, poles, joists, or boards, you can make a frame in some one of the ways figured here, and throw your tents over it.

These frames will be found useful for other purposes, and it is well to remember how to make them.

CHAPTER IX

TENTS.—ARMY SHELTER-TENT (tente d'abri)

The shelter-tent used by the Union soldiers during the Rebellion was made of light duck12 about 31-1/2 inches wide. A tent was made in two pieces both precisely alike, and each of them five feet long and five feet and two inches wide; i.e., two widths of duck. One of these pieces or half-tents was given to every soldier. That edge of the piece which was the bottom of the tent was faced at the corners with a piece of stouter duck three or four inches square. The seam in the middle of the piece was also faced at the bottom, and eyelets were worked at these three places, through which stout cords or ropes could be run to tie this side of the tent down to the tent-pin, or to fasten it to whatever else was handy. Along the other three edges of each piece of tent, at intervals of about eight inches, were button-holes and buttons; the holes an inch, and the buttons four inches, from the selvage or hem.13

Two men could button their pieces at the tops, and thus make a tent entirely open at both ends, five feet and two inches long, by six to seven feet wide according to the angle of the roof. A third man could button his piece across one of the open ends so as to close it, although it did not make a very neat fit, and half of the cloth was not used; four men could unite their two tents by buttoning the ends together, thus doubling the length of the tent; and a fifth man could put in an end-piece.

Light poles made in two pieces, and fastened together with ferrules so as to resemble a piece of fishing-rod, were given to some of the troops when the tents were first introduced into the army; but, nice as they were at the end of the march, few soldiers would carry them, nor will you many days.

The tents were also pitched by throwing them over a tightened rope; but it was easier to cut a stiff pole than to carry either the pole or rope.

You need not confine yourself exactly to the dimensions of the army shelter-tent, but for a pedestrian something of the sort is necessary if he will camp out. I have never seen a "shelter" made of three breadths of drilling (seven feet three inches long), but I should think it would be a good thing for four or five men to take.14 And I should recommend that they make three-sided end-pieces instead of taking additional half-tents complete, for in the latter case one-half of the cloth is useless.

Five feet is long enough for a tent made on the "shelter" principle; when pitched with the roof at a right angle it is 3-1/2 feet high, and nearly seven feet wide on the ground.