полная версия

полная версияHow to Camp Out

Those who wish to become familiar with the details of bird-collecting will find a treasure in the doctor's book, "Field Ornithology, comprising a Manual of Instruction for procuring, preparing, and preserving Birds; and a check list of North American Birds. By Dr. Elliott Coues, U.S.A. Salem: Naturalists' Agency."]

ACCIDENTS

The secret of safe climbing is never to relax one hold until another is secured; it is in spirit equally applicable to scrambling over rocks, a particularly difficult thing to do safely with a loaded gun. Test rotten, slippery, or otherwise suspicious holds, before trusting them. In lifting the body up anywhere, keep the mouth shut, breathe through the nostrils, and go slowly.

In swimming waste no strength unnecessarily in trying to stem a current; yield partly, and land obliquely lower down; if exhausted, float: the slightest motion of the hands will ordinarily keep the face above water; in any event keep your wits collected. In fording deeply, a heavy stone [in the hands, above water] will strengthen your position.

Never sail a boat experimentally: if you are no sailor, take one with you, or stay on land.

In crossing a high narrow foot-path, never look lower than your feet; the muscles will work true if not confused with faltering instructions from a giddy brain. On soft ground see what, if any thing, has preceded you; large hoof-marks generally mean that the way is safe: if none are found, inquire for yourself before going on. Quicksand is the most treacherous because far more dangerous than it looks; but I have seen a mule's ears finally disappear in genuine mud.

Cattle-paths, however erratic, commonly prove the surest way out of a difficult place, whether of uncertain footing or dense undergrowth.

"TAKING COLD."

This vague "household word" indicates one or more of a long varied train of unpleasant affections nearly always traceable to one or the other of only two causes,—sudden change of temperature, and unequal distribution of temperature. No extremes of heat or cold can alone affect this result: persons frozen to death do not "take cold" during the process. But if a part of the body be rapidly cooled, as by evaporation from a wet article of clothing, or by sitting in a draught of air, the rest of the body remaining at an ordinary temperature; or if the temperature of the whole be suddenly changed by going out into the cold, or especially by coming into a warm room,—there is much liability of trouble.

There is an old saying,—

"When the air comes through a hole,Say your prayers to save your soul."And I should think almost any one could get a "cold " with a spoonful of water on the wrist held to a key-hole. Singular as it may seem, sudden warming when cold is more dangerous than the reverse: every one has noticed how soon the handkerchief is required on entering a heated room on a cold day. Frost-bite is an extreme illustration of this. As the Irishman said on picking himself up, it was not the fall, but stopping so quickly, that hurt him: it is not the lowering of the temperature to freezing point, but its subsequent elevation, that devitalizes the tissue. This is why rubbing with snow, or bathing in cold water, is required to restore safely a frozen part: the arrested circulation must be very gradually re-established, or inflammation, perhaps mortification, ensues.

General precautions against taking cold are almost self-evident in this light. There is ordinarily little if any danger to be apprehended from wet clothes, so long as exercise is kept up; for the "glow" about compensates for the extra cooling by evaporation. Nor is a complete drenching more likely to be injurious than wetting of one part. But never sit still wet, and in changing rub the body dry. There is a general tendency, springing from fatigue, indolence, or indifference, to neglect damp feet,—that is to say, to dry them by the fire; but this process is tedious and uncertain. I would say especially, "Off with muddy boots and sodden socks at once:" dry stockings and slippers after a hunt may make just the difference of your being able to go out again, or never. Take care never to check perspiration: during this process the body is in a somewhat critical condition, and the sudden arrest of the function may result disastrously, even fatally. One part of the business of perspiration is to equalize bodily temperature, and it must not be interfered with. The secret of much that is said about bathing when heated lies here. A person overheated, panting it may be, with throbbing temples and a dry skin, is in danger partly because the natural cooling by evaporation from the skin is denied; and this condition is sometimes not far from a "sunstroke." Under these circumstances, a person of fairly good constitution may plunge into the water with impunity, even with benefit. But, if the body be already cooling by sweating, rapid abstraction of heat from the surface may cause internal congestion, never unattended with danger.

Drinking ice-water offers a somewhat parallel case; even on stopping to drink at the brook, when flushed with heat, it is well to bathe the face and hands first, and to taste the water before a full draught. It is a well-known excellent rule, not to bathe immediately after a full meal; because during digestion the organs concerned are comparatively engorged and any sudden disturbance of the circulation may be disastrous.

The imperative necessity of resisting drowsiness under extreme cold requires no comment.

In walking under a hot sun, the head may be sensibly protected by green leaves or grass in the hat; they may be advantageously moistened, but not enough to drip about the ears. Under such circumstances the slightest giddiness, dimness of sight, or confusion of ideas, should be taken as a warning of possible sunstroke, instantly demanding rest, and shelter if practicable.

HUNGER AND FATIGUE

are more closely related than they might seem to be: one is a sign that the fuel is out, and the other asks for it. Extreme fatigue, indeed, destroys appetite: this simply means temporary incapacity for digestion. But, even far short of this, food is more easily digested and better relished after a little preparation of the furnace. On coming home tired it is much better to make a leisurely and reasonably nice toilet, than to eat at once, or to lie still thinking how tired you are; after a change and a wash you feel like a "new man," and go to the table in capital state. Whatever dietetic irregularities a high state of civilization may demand or render practicable, a normally healthy person is inconvenienced almost as soon as his regular mealtime passes without food; and few can work comfortably or profitably fasting over six or eight hours. Eat before starting; if for a day's tramp, take a lunch; the most frugal meal will appease if it do not satisfy hunger, and so postpone its urgency. As a small scrap of practical wisdom, I would add, Keep the remnants of the lunch if there be any; for you cannot always be sure of getting in to supper.

STIMULATION

When cold, fatigued, depressed in mind, and on other occasions, you may feel inclined to resort to artificial stimulus. Respecting this many-sided theme I have a few words to offer—of direct bearing on the collector's case. It should be clearly understood, in the first place, that a stimulant confers no strength whatever: it simply calls the powers that be into increased action, at their own expense. Seeking real strength in stimulus is as wise as an attempt to lift yourself up by your boot-straps. You may gather yourself to leap the ditch, and you clear it; but no such muscular energy can be sustained: exhaustion speedily renders further expenditure impossible. But now suppose a very powerful mental impression be made, say the circumstance of a succession of ditches in front, and a mad dog behind: if the stimulus of terror be sufficiently strong, you may leap on till you drop senseless. Alcoholic stimulus is a parallel case, and is not seldom pushed to the same extreme. Under its influence you never can tell when you are tired; the expenditure goes on, indeed, with unnatural rapidity, only it is not felt at the time; but the upshot is, you have all the original fatigue to endure and to recover from, plus the fatigue resulting from over-excitation of the system. Taken as a fortification against cold, alcohol is as unsatisfactory as a remedy for fatigue. Insensibility to cold does not imply protection. The fact is, the exposure is greater than before; the circulation and respiration being hurried, the waste is greater; and, as sound fuel cannot be immediately supplied, the temperature of the body is soon lowered. The transient warmth and glow over the system has both cold and depression to endure. There is no use in borrowing from yourself, and fancying you are richer.

Secondly, the value of any stimulus (except in a few exigencies of disease or injury) is in proportion, not to the intensity, but to the equableness and durability, of its effect. This is one reason why tea, coffee, and articles of corresponding qualities, are preferable to alcoholic drinks: they work so smoothly that their effect is often unnoticed, and they "stay by" well. The friction of alcohol is tremendous in comparison. A glass of grog may help a veteran over the fence; but no one, young or old, can shoot all day on whiskey.

I have had so much experience in the use of tobacco as a mild stimulant, that I am probably no impartial judge of its merits. I will simply say, I do not use it in the field, because it indisposes to muscular activity, and favors reflection when observation is required; and because temporary abstinence provokes the morbid appetite, and renders the weed more grateful afterwards.

Thirdly, undue excitation of any physical function is followed by a corresponding depression, on the simple principle that action and reaction are equal; and the balance of health turns too easily to be wilfully disturbed. Stimulation is a draft upon vital capital, when interest alone should suffice: it may be needed at times to bridge a chasm; but habitual living beyond vital income infallibly entails bankruptcy in health. The use of alcohol in health seems practically restricted to purposes of sensuous gratification on the part of those prepared to pay a round price for this luxury. The three golden rules here are,—Never drink before breakfast; never drink alone; and never drink bad liquor. Their observance may make even the abuse of alcohol tolerable. Serious objections, for a naturalist at least, are that science, viewed through a glass, seems distant and uncertain, while the joys of rum are immediate and unquestionable; and that intemperance, being an attempt to defy certain physical laws, is therefore eminently unscientific.

Besides the above good advice by Dr. Coues, the following may prove useful to the camper:—

Diarrhœa may result from overwork and gluttony combined, and from eating indigestible or uncooked food, and from imperfect protection of the stomach. "Remove the cause, and the effect will cease." A flannel bandage six to twelve inches wide, worn around the stomach, is good as a preventive and cure.

The same causes may produce cholera morbus; symptoms, violent vomiting and purging, faintness, and spasms in the arms and limbs. Unless accompanied with cramp (which is not usual), nature will work its own cure. Give warm drinks if you have them. Do not get frightened, but keep the patient warm, and well protected from a draught of air.

The liability to costiveness, and the remedies therefor, are noted on p. 55 of this book.

A very rare occurrence, but a constant dread with some people, is an insect crawling into the ear. If you have oil, spirits of turpentine, or alcoholic liquor at hand, fill the ear at once. If you have not these, use coffee, tea, warm water (not too hot), or almost any liquid which is not hurtful to the skin.

MARSHALL HALL'S READY METHOD IN SUFFOCATION, DROWNING, ETC

1st, Treat the patient instantly on the spot, in the open air, freely exposing the face, neck, and chest to the breeze, except in severe weather.

2d, In order to clear the throat, place the patient gently on the face, with one wrist under the forehead, that all fluid, and the tongue itself, may fall forward, and leave the entrance into the windpipe free.

3d, To excite respiration, turn the patient slightly on his side, and apply some irritating or stimulating agent to the nostrils, as veratrine, dilute ammonia, &c.

4th, Make the face warm by brisk friction; then dash cold water upon it.

5th, If not successful, lose no time; but, to imitate respiration, place the patient on his face, and turn the body gently but completely on the side and a little beyond, then again on the face, and so on alternately. Repeat these movements deliberately and perseveringly, fifteen times only in a minute. (When the patient lies on the thorax, this cavity is compressed by the weight of the body, and expiration takes place. When he is turned on the side, this pressure is removed, and inspiration occurs.)

6th, When the prone position is resumed, make a uniform and efficient pressure along the spine, removing the pressure immediately, before rotation on the side. (The pressure augments the expiration, the rotation commences inspiration.) Continue these measures.

7th, Rub the limbs upward, with firm pressure and with energy. (The object being to aid the return of venous blood to the heart.)

8th, Substitute for the patient's wet clothing, if possible, such other covering as can be instantly procured, each bystander supplying a coat or cloak, &c. Meantime, and from time to time, to excite inspiration, let the surface of the body be slapped briskly with the hand.

9th, Rub the body briskly till it is dry and warm, then dash cold water upon it, and repeat the rubbing.

Avoid the immediate removal of the patient, as it involves a dangerous loss of time; also the use of bellows or any forcing instrument; also the warm bath and all rough treatment.

POISONS

In all cases of poisoning, the first step is to evacuate the stomach. This should be effected by an emetic which is quickly obtained, and most powerful and speedy in its operation. Such are, powdered mustard (a large tablespoonful in a tumblerful of warm water), powdered alum (in half-ounce doses), sulphate of zinc (ten to thirty grains), tartar emetic (one to two grains) combined with powdered ipecacuanha (twenty grains), and sulphate of copper (two to five grains). When vomiting has already taken place, copious draughts of warm water or warm mucilaginous drinks should be given, to keep up the effect till the poisoning substance has been thoroughly evacuated.

PARTING ADVICE

Be independent, but not impudent. See all you can, and make the most of your time; "time is money;" and, when you grow older, you may find it even more difficult to command time than money.

1

If your haversack-flap has a strap which buckles down upon the front, you can run the strap through the cup-handle before buckling; or you can buy a rein-hitch at the saddlery-hardware shop, and fasten it wherever most convenient to carry the cup.

2

A German officer tells me that his comrades in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-1 had no rubber blankets; nor had they any shelter-tents such as our Union soldiers used in 1861-5 as a make-shift when their rubbers were lost. But this is nothing to you: German discipline compelled the soldiers to carry a big cloak which sheds water quite well, and is useful to a soldier for other purposes: but the weight and bulk condemn it for pleasure-seekers.

3

In general it is better to put the shelter-tent in the roll, and to keep out the rubber blanket, for you may need the last before you camp. You can roll the rubber blanket tightly around the other roll (the cloth side out, as the rubber side is too slippery), and thus be able to take it off readily without disturbing the other things. You can also roll the rubber blanket separately, and link it to the large roll after the manner of two links of a chain.

4

I knew an officer in the army, who carried a rubber air-pillow through thick and thin, esteeming it, after his life and his rations, the greatest necessity of his existence. Another officer, when transportation was cut down, held to his camp-chair. Almost every one has his whim.

5

I never heard of a party exclusively of young men going on a tour of this kind, and consequently I cannot write their experiences; but I can easily imagine their troubles, quarrels, and separation into cliques. I once went as captain of a party of ten, composed of ladies, gentlemen, and schoolboys. We walked around the White Mountains from North Conway to Jefferson and back, by way of Jackson. It cost each of us a dollar and thirty-two cents a day for sixteen days, including railroad fares to and from Portland, but excluding the cost of clothes, tents, and cooking-utensils. Another time a similar party of twelve walked from Centre Harbor, N.H., to Bethel, Me., in seventeen days, at a daily cost of a dollar and two cents, reckoning as before. In both cases, "my right there was none to dispute;" and by borrowing a horse the first time, and selling at a loss of only five dollars the second, our expenses for the horse were small.

6

In one of my tours around the mountains, a lad of sixteen, in attempting to hold up the horse's head as they were running down hill, was hit by the horse's fore-leg, knocked down, and run over by both wheels.

7

Some of the questions which properly belong under this heading are discussed elsewhere, and can be found by referring to the index.

8

This advice also differs from that generally given to soldiers; the army rule is as follows: "Drink well in the morning before starting, and nothing till the halt; keep the mouth shut; chew a straw or leaf, or keep the mouth covered with a cloth: all these prevent suffering from extreme thirst. Tying a handkerchief well wetted with salt water around the neck, allays thirst for a considerable time."—Craghill's Pocket Companion: Van Nostrand, N.Y.

9

Barrel-staves will not do for a double bed.

10

It will roll up easier if the quilting runs from side to side only.

11

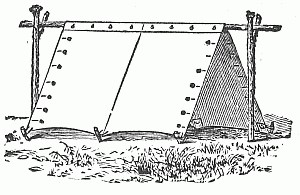

This applies, as will be seen, only to tents having two uprights, as the wall, "A," and shelter.

12

You cannot find this sort of duck in the market now, but "heavy drilling" 29-1/2 inches wide is nearly as strong, and will make a good tent.

13

Tents made of heavy drilling were also furnished to the troops, the dimensions of which varied a trifle from those here given: they had the disadvantage of two seams instead of one.

14

If the party is of four, or even five, a shelter-tent made of three breadths of heavy drilling will accommodate all. Sew one end-piece to each half-tent, since sewing is better than buttoning, and the last is not necessary when your party will always camp together. Along the loose border of the end-piece work the button-holes, and sew the corresponding buttons upon the main tent an inch or more from the edge of the border. Sew on facings at the corners and seams as in the army shelter, and also on the middle of the bottom of the end-pieces; and put loops of small rope or a foot or two of stout cord through all of these facings, for the tent-pins. You will then have a tent with the least amount of labor and material in it. The top edges, like those of the army shelter, are to have buttons and button-holes; the tent can then be taken apart into two pieces, each of which will weigh about two pounds and a quarter. Nearly all of the work can be done on a sewing-machine; run two rows of stitching at each seam as near the selvage as you can.

15

Called also wedge-tent.

16

To find the distance of the corners, multiply the width of the cloth (29-1/2 inches) by 3 (three breadths), and subtract 2-1/4 inches (or three overlappings of 3/4 inch each, as will be explained).

17

What is known by shoemakers as "webbing" is good for this purpose, or you can double together and sew strips of sheeting or drilling. Cod-lines and small ropes are objectionable, as they are not easily untied when in hard knots.

18

The poles for army A-tents are seven feet six inches.

19

This name is given to the piece of wood that tightens the guy-line. The United States army tent has a fiddle 5-1/4 inches long, 1-3/4 wide, and 1 inch thick; the holes are 3-1/2 inches apart from centre to centre. If you make a fiddle shorter, or of thinner stock, it does not hold its grip so well. One hole should be just large enough to admit the rope, and the other a size larger so that the rope may slide through easily.

20

Seven-ounce duck is made, but it is not much heavier than drilling, and since it is little used it is not easily found for sale. United States army wall-tents are made from a superior quality of ten-ounce duck, but they are much stouter than is necessary for summer camping. There are also "sail-ducks," known as "No. 8," "No. 9," &c., which are very much too heavy for tents.

21

The length of tent-poles, as has been previously stated, depends upon the size of the tent.

22

What are known as "bolt-ends" can be bought at the hardware stores for this purpose.

23

A flannel dress, the skirt coming to the top of the boots, and having a blouse waist, will be found most comfortable.

24

It is no novelty for women and children to camp out: we see them every summer at the seaside and on the blueberry-plains. A great many families besides live in rude cabins, which are preferable on many accounts, but are expensive. Sickness sometimes results, but usually all are much benefited. I know a family that numbered with its guests nine ladies, five children ("one at the breast"), and the paterfamilias, which camped several weeks through some of the best and some of the worst of weather. The whooping-cough broke out the second or third day; shortly after, the tent of the mother and children blew down in the night, and turned them all out into the pelting rain in their night-clothes. Excepting the misery of that night and day, nothing serious came of it; and in the fall all returned home better every way for having spent their summer in camp.

25

The mesh of a net is measured by pulling it diagonally as far as possible, and finding the distance from knot to knot; consequently a three-inch mesh will open so as to make a square of about an inch and a half.

26

The field allowance in the United States army is nearly 1-1/8 pounds of coffee and 2-1/8 pounds of sugar (damp brown) for two men seven days; the bread and pork ration is also larger than that above given; but the allowance of potatoes is almost nothing.

27

How to Do It. Published by Roberts Brothers, Boston.