полная версия

полная версияHow to Camp Out

In this arrangement there is nothing to prevent one member from aiding another; in fact, where all are employed, a better feeling prevails, and, the work being done more quickly, there is more time for rest and enjoyment.

To get a horse will perhaps tax your judgment and capability as much as any thing in all your preparation; and on this point, where you need so much good advice, I can only give you that of a general nature.

The time for camping out is when horses are in greatest demand for farming purposes; and you will find it difficult to hire of any one except livery-stable men, whose charges are so high that you cannot afford to deal with them. You will have to hunt a long time, and in many places, before you will find your animal. It is not prudent to take a valuable horse, and I advise you not to do so unless the owner or a man thoroughly acquainted with horses is in the party. You may perhaps be able to hire horse, wagon, and driver; but a hired man is an objectionable feature, for, besides the expense, such a man is usually disagreeable company.

My own experience is, that it is cheaper to buy a horse outright, and to hire a harness and wagon; and, since I am not a judge of horse-flesh, I get some friend who is, to go with me and advise. I find that I can almost always buy a horse, even when I cannot hire. Twenty to fifty dollars will bring as good an animal as I need. He may be old, broken down, spavined, wind-broken, or lame; but if he is not sickly, or if his lameness is not from recent injury, it is not hard for him to haul a fair load ten or fifteen miles a day, when he is helped over the hard places.

So now, if you pay fifty dollars for a horse, you can expect to sell him for about twenty or twenty-five dollars, unless you were greatly cheated, or have abused your brute while on the trip, both of which errors you must be careful to avoid. It is a simple matter of arithmetic to calculate what is best for you to do; but I hope on this horse question you may have the benefit of advice from some one who has had experience with the ways of the world. You will need it very much.

WAGONS

If you have the choice of wagons, take one that is made for carrying light, bulky goods, for your baggage will be of that order. One with a large body and high sides, or a covered wagon, will answer. In districts where the roads are mountainous, rough, and rocky, wagons hung on thoroughbraces appear to suit the people the best; but you will have no serious difficulty with good steel springs if you put in rubber bumpers, and also strap the body to the axles, thus preventing the violent shutting and opening of the springs; for you must bear in mind that the main leaf of a steel spring is apt to break by the sudden pitching upward of the wagon-body.

It has been my fortune twice to have to carry large loads in small low-sided wagons; and it proved very convenient to have two or three half-barrels to keep food and small articles in, and to roll the bedding in rolls three or four feet wide, which were packed in the wagon upon their ends. The private baggage was carried in meal-bags, and the tents in bags made expressly to hold them; we could thus load the wagon securely with but little tying.

For wagons with small and low bodies, it would be well to put a light rail fourteen to eighteen inches above the sides, and hold it there by six or eight posts resting on the floor, and confined to the sides of the body.

Drive carefully and slowly over bad places. It makes a great deal of difference whether a wheel strikes a rock with the horse going at a trot, or at a walk.

HARNESS

If your load is heavy, and the roads very hard, or the daily distance long, you had better have a collar for the horse: otherwise a breastplate-harness will do. In your kit of tools it is well to have a few straps, an awl, and waxed ends, against the time that something breaks. Oil the harness before you start, and carry about a pint of neat's-foot oil, which you can also use upon the men's boots. At night look out that the harness and all of your baggage are sheltered from dew and rain, rats and mice.

ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF THIS MODE OF TRAVEL

This way of travelling is peculiarly adapted to a party of different ages, rather than for one exclusively of young men. It is especially suitable where there are ladies who wish to walk and camp, or for an entire family, or for a school with its teachers. The necessity of a head to a party will hardly be recognized by young men; and, even if it is, they are still unwilling, as a general rule, to submit to unaccustomed restraint.

The way out of this difficulty is for one man to invite his comrades to join his party, and to make all the others understand, from first to last, that they are indebted to him for the privilege of going. It is then somewhat natural for the invited guests to look to their leader, and to be content with his decisions.

The best of men get into foolish dissensions when off on a jaunt, unless there is one, whose voice has authority in it, to direct the movements.

I knew a party of twenty or more that travelled in this way, and were directed by a trio composed of two gentlemen and one lady. This arrangement proved satisfactory to all concerned.5

It has been assumed in all cases that some one will lead the horse,—not ride in the loaded wagon,—and that two others will go behind and not far off, to help the horse over the very difficult places, as well as to have an eye on the load, that none of it is lost off, or scrapes against the wheels. Whoever leads must be careful not to fall under the horse or wagon, nor to fall under the horse's feet, should he stumble. These are daily and hourly risks: hence no small boy should take this duty.6

CHAPTER IV

CLOTHING

If your means allow it, have a suit especially for the summer tour, and sufficiently in fashion to indicate that you are a traveller or camper.

SHIRTS

Loose woollen shirts, of dark colors and with flowing collars, will probably always be the proper thing. Avoid gaudiness and too much trimming. Large pockets, one over each breast, are "handy;" but they spoil the fit of the shirt, and are always wet from perspiration. I advise you to have the collar-binding of silesia, and fitted the same as on a cotton shirt, only looser; then have a number of woollen collars (of different styles if you choose), to button on in the same manner as a linen collar. You can thus keep your neck cool or warm, and can wash the collars, which soil so easily, without washing the whole shirt. The shirt should reach nearly to the knees, to prevent disorders in the stomach and bowels. There are many who will prefer cotton-and-wool goods to all-wool for shirts. The former do not shrink as much, nor are they as expensive, as the latter.

DRAWERS

If you wear drawers, better turn them inside out, so that the seams may not chafe you. They must be loose.

SHOES

You need to exercise more care in the selection of shoes than of any other article of your outfit. Tight boots put an end to all pleasure, if worn on the march; heavy boots or shoes, with enormously thick soles, will weary you; thin boots will not protect the feet sufficiently, and are liable to burst or wear out; Congress boots are apt to bind the cords of the leg, and thus make one lame; short-toed boots or shoes hurt the toes; loose ones do the same by allowing the foot to slide into the toe of the boot or shoe; low-cut shoes continually fill with dust, sand, or mud.

For summer travel, I think you can find nothing better than brogans reaching above the ankles, and fastening by laces or buttons as you prefer, but not so tight as to bind the cords of the foot. See that they bind nowhere except upon the instep. The soles should be wide, and the heels wide and low (about two and three-quarter inches wide by one inch high); have soles and heels well filled with iron nails. Be particular not to have steel nails, which slip so badly on the rocks.

Common brogans, such as are sold in every country-store, are the next best things to walk in; but it is hard to find a pair that will fit a difficult foot, and they readily let in dust and earth.

Whatever you wear, break them in well, and oil the tops thoroughly with neat's-foot oil before you start; and see that there are no nails, either in sight or partly covered, to cut your feet.

False soles are a good thing to have if your shoes will admit them: they help in keeping the feet dry, and in drying the shoes when they are wet.

Woollen or merino stockings are usually preferable to cotton, though for some feet cotton ones are by far the best. Any darning should be done smoothly, since a bunch in the stocking is apt to bruise the skin.

PANTALOONS

Be sure to have the trousers loose, and made of rather heavier cloth than is usually worn at home in summer. They should be cut high in the waist to cover the stomach well, and thus prevent sickness.

The question of wearing "hip-pants," or using suspenders, is worth some attention. The yachting-shirt by custom is worn with hip-pantaloons, and often with a belt around the waist; and this tightening appears to do no mischief to the majority of people. Some, however, find it very uncomfortable, and others are speedily attacked by pains and indigestion in consequence of having a tight waist. If you are in the habit of wearing suspenders, do not change now. If you do not like to wear them over the shirt, you can wear them over a light under-shirt, and have the suspender straps come through small holes in the dress-shirt. In that case cut the holes low enough so that the dress-shirt will fold over the top of the trousers, and give the appearance of hip-pantaloons. If you undertake to wear the suspenders next to the skin, they will gall you. A fortnight's tramping and camping will about ruin a pair of trousers: therefore it is not well to have them made of any thing very expensive.

Camping offers a fine opportunity to wear out old clothes, and to throw them away when you have done with them. You can send home by mail or express your soiled underclothes that are too good to lose or to be washed by your unskilled hands.

CHAPTER V

STOVES AND COOKING-UTENSILS

If you have a permanent camp, or if moving you have wagon-room enough, you will find a stove to be most valuable property. If your party is large it is almost a necessity.

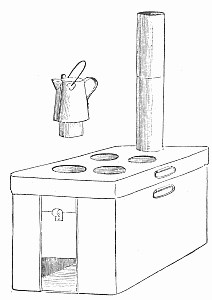

For a permanent camp you can generally get something second-hand at a stove-dealer's or the junk-shop. For the march you will need a stove of sheet iron. About the simplest, smallest, and cheapest thing is a round-cornered box made of sheet iron, eighteen to twenty-four inches long and nine to twelve inches high. It needs no bottom: the ground will answer for that. The top, which is fixed, is a flat piece of sheet iron, with a hole near one end large enough for a pot or pan, and a hole (collar) for the funnel near the other end. It is well also to have a small hole, with a slide to open and close it with, in the end of the box near the bottom, so as to put in wood, and regulate the draught; but you can dispense with the slide by raising the stove from the ground when you want to admit fuel or air.

I have used a more elaborate article than this. It is an old sheet-iron stove that came home from the army, and has since been taken down the coast and around the mountains with parties of ten to twenty. It was almost an indispensable article with such large companies. It is a round-cornered box, twenty-one inches long by twenty wide, and thirteen inches high, with a slide in the front end to admit air and fuel. The bottom is fixed to the body; the top removes, and is fitted loosely to the body after the style of a firkin-cover, i.e., the flange, which is deep and strong, goes outside the stove. There are two holes on the top 5-1/2 inches in diameter, and two 7-1/2 inches, besides the collar for the funnel; and these holes have covers neatly fitted. All of the cooking-utensils and the funnel can be packed inside the stove; and, if you fear it may upset on the march, you can tie the handles of the stove to those of the top piece.

A stove like this will cost about ten dollars; but it is a treasure for a large party or one where there are ladies, or those who object to having their eyes filled with smoke. The coffee-pot and tea-pot for this stove have "sunk bottoms," and hence will boil quicker by presenting more surface to the fire. You should cover the bottom of the stove with four inches or more of earth before making a fire in it.

To prevent the pots and kettles from smutting every thing they touch, each has a separate bag in which it is packed and carried.

The funnel was in five joints, each eighteen inches long, and made upon the "telescope" principle, which is objectionable on account of the smut and the jams the funnel is sure to receive. In practice we have found three lengths sufficient, but have had two elbows made; and with these we can use the stove in an old house, shed, or tent, and secure good draught.

If you have ladies in your party, or those to whom the rough side of camping-out offers few attractions, it is well to consider this stove question. Either of these here described must be handled and transported with care.

A more substantial article is the Dutch oven, now almost unknown in many of the States. It is simply a deep, bailed frying-pan with a heavy cast-iron cover that fits on and overhangs the top. By putting the oven on the coals, and making a fire on the cover, you can bake in it very well. Thousands of these were used by the army during the war, and they are still very extensively used in the South. If their weight is no objection to your plans, I should advise you to have a Dutch oven. They are not expensive if you can find one to buy. If you cannot find one for sale, see if you cannot improvise one in some way by getting a heavy cover for a deep frying-pan. It would be well to try such an improvisation at home before starting, and learn if it will bake or burn, before taking it with you.

Another substitute for a stove is one much used nowadays by camping-parties, and is suited for permanent camps. It is the top of an old cooking-stove, with a length or two of funnel. If you build a good tight fireplace underneath, it answers pretty well. The objection to it is the difficulty of making and keeping the fireplace tight, and it smokes badly when the wind is not favorable for draught. I have seen a great many of these in use, but never knew but one that did well in all weathers, and this had a fireplace nicely built of brick and mortar, and a tight iron door.

Still another article that can be used in permanent camps, or if you have a wagon, is the old-fashioned "Yankee baker," now almost unknown. You can easily find a tinman who has seen and can make one. There is not, however, very often an occasion for baking in camp, or at least most people prefer to fry, boil, or broil.

Camp-stoves are now a regular article of trade; many of them are good, and many are worthless. I cannot undertake to state here the merits or demerits of any particular kind; but before putting money into any I should try to get the advice of some practical man, and not buy any thing with hinged joints or complicated mechanism.

CHAPTER VI

COOKING, AND THE CARE OF FOOD

When living in the open air the appetite is so good, and the pleasure of getting your own meals is so great, that, whatever may be cooked, it is excellent.

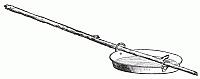

You will need a frying-pan and a coffee-pot, even if you are carrying all your baggage upon your back. You can do a great deal of good cooking with these two utensils, after having had experience; and it is experience, rather than recipes and instructions, that you need. Soldiers in the field used to unsolder their tin canteens, and make two frying-pans of them; and I have seen a deep pressed-tin plate used by having two loops riveted on the edges opposite each other to run a handle through. Food fried in such plates needs careful attention and a low fire; and, as the plates themselves are somewhat delicate, they cannot be used roughly.

It is far better to carry a real frying-pan, especially if there are three or more in your party. If you have transportation, or are going into a permanent camp, do not think of the tin article.

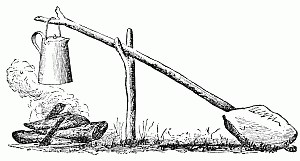

A coffee-pot with a bail and handle is better than one with a handle only, and a lip is better than a spout; since handles and spouts are apt to unsolder.

Young people are apt to put their pot or frying-pan on the burning wood, and it soon tips over. Also they let the pot boil over, and presently it unsolders for want of water. Few think to keep the handle so that it can be touched without burning or smutting; and hardly any young person knows that pitchy wood will give a bad flavor to any thing cooked over it on an open fire. Live coals are rather better, therefore, than the blaze of a new fire.

If your frying-pan catches fire inside, do not get frightened, but take it off instantly, and blow out the fire, or smother it with the cover or a board if you cannot blow it out.

You will do well to consult a cook-book if you wish for variety in your cooking; but some things not found in cook-books I will give you here.

Stale bread, pilot-bread, dried corn-cakes, and crumbs, soaked a few minutes in water, or better still in milk, and fried, are all quite palatable.

In frying bread, or any thing else, have the fat boiling hot before you put in the food: this prevents it from soaking fat.

BAKED BEANS, BEEF, AND FISH

Lumbermen bake beans deliciously in an iron pot that has a cover with a projecting rim to prevent the ashes from getting in the pot. The beans are first parboiled in one or two waters until the outside skin begins to crack. They are then put into the baking-pot, and salt pork at the rate of a pound to a quart and a half of dry beans is placed just under the surface of the beans. The rind of the pork should be gashed so that it will cut easily after baking. Two or three tablespoonfuls of molasses are put in, and a little salt, unless the pork is considerably lean. Water enough is added to cover the beans.

A hole three feet or more deep is dug in the ground, and heated for an hour by a good hot fire. The coals are then shovelled out, and the pot put in the hole, and immediately buried by throwing back the coals, and covering all with dry earth. In this condition they are left to bake all night.

On the same principle very tough beef was cooked in the army, and made tender and juicy. Alternate layers of beef, salt pork, and hard bread were put in the pot, covered with water, and baked all night in a hole full of coals.

Fish may also be cooked in the same way. It is not advisable, however, for parties less than six in number to trouble themselves to cook in this manner.

CARE OF FOOD

You had better carry butter in a tight tin or wooden box. In permanent camp you can sink it in strong brine, and it will keep some weeks. Ordinary butter will not keep sweet a long time in hot weather unless in a cool place or in brine. Hence it is better to replenish your stock often, if it is possible for you to do so.

You perhaps do not need to be told that when camping or marching it is more difficult to prevent loss of food from accidents, and from want of care, than when at home. It is almost daily in danger from rain, fog, or dew, cats and dogs, and from flies or insects. If it is necessary for you to take a large quantity of any thing, instead of supplying yourself frequently, you must pay particular attention to packing, so that it shall neither be spoiled, nor spoil any thing else.

You cannot keep meats and fish fresh for many hours on a summer day; but you may preserve either over night, if you will sprinkle a little salt upon it, and place it in a wet bag of thin cloth which flies cannot go through; hang the bag in a current of air, and out of the reach of animals.

In permanent camp it is well to sink a barrel in the earth in some dry, shaded place; it will answer for a cellar in which to keep your food cool. Look out that your cellar is not flooded in a heavy shower, and that ants and other insects do not get into your food.

The lumbermen's way of carrying salt pork is good. They take a clean butter-tub with four or five gimlet-holes bored in the bottom near the chimbs. Then they pack the pork in, and cover it with coarse salt; the holes let out what little brine makes, and thus they have a dry tub. Upon the pork they place a neatly fitting "follower," with a cleat or knob for a handle, and then put in such other eatables as they choose. Pork can be kept sweet for a few weeks in this way, even in the warmest weather; and by it you avoid the continual risk of upsetting and losing the brine. Before you start, see that the cover of the firkin is neither too tight nor too loose, so that wet or dry weather may not affect it too much.

I beg you to clean and wash your dishes as soon as you have done using them, instead of leaving them till the next meal. Remember to take dishcloths and towels, unless your all is a frying-pan and coffee-pot that you are carrying upon your back, when leaves and grass must be made to do dishcloth duty.

CHAPTER VII

MARCHING. 7

It is generally advised by medical men to avoid violent exercise immediately after eating. They are right; but I cannot advise you to rest long, or at all, after breakfast, but rather to finish what you could not do before the meal, and get off at once while it is early and cool. Do not hurry or work hard at first if you can avoid it.

On the march, rest often whether you feel tired or not; and, when resting, see that you do rest.

The most successful marching that I witnessed in the army was done by marching an hour, and resting ten minutes. You need not adhere strictly to this rule: still I would advise you to halt frequently for sight-seeing, but not to lie perfectly still more than five or ten minutes, as a reaction is apt to set in, and you will feel fatigued upon rising.

Experience has shown that a man travelling with a light load, or none, will walk about three miles an hour; but you must not expect from this that you can easily walk twelve miles in four heats of three miles each with ten minutes rest between, doing it all in four and a half hours. Although it is by no means difficult, my advice is for you not to expect to walk at that rate, even through a country that you do not care to see. You may get so used to walking after a while that these long and rapid walks will not weary you; but in general you require more time, and should take it.

Do not be afraid to drink good water as often as you feel thirsty; but avoid large draughts of cold water when you are heated or are perspiring, and never drink enough to make yourself logy. You are apt to break these rules on the first day in the open air, and after eating highly salted food. You can often satisfy your thirst with simply rinsing the mouth. You may have read quite different advice8 from this, which applies to those who travel far from home, and whose daily changes bring them to water materially different from that of the day before.

It is well to have a lemon in the haversack or pocket: a drop or two of lemon-juice is a great help at times; but there is really nothing which will quench the thirst that comes the first few days of living in the open air. Until you become accustomed to the change, and the fever has gone down, you should try to avoid drinking in a way that may prove injurious. Base-ball players stir a little oatmeal in the water they drink while playing, and it is said they receive a healthy stimulus thereby.