полная версия

полная версияThe Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783

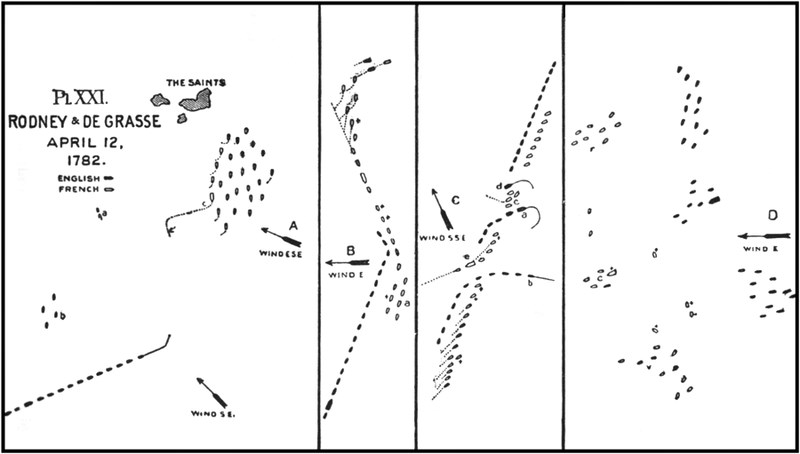

At daylight206 (about half-past five) the English fleet, which had gone about at two A.M., was standing on the starboard tack, with the wind at southeast,207 an unusual amount of southing for that hour (Plate XXI., A). It was then about fifteen miles from the Saints, which bore north-northeast, and ten from the French fleet, which bore northeast. The latter, owing to the events of the night, was greatly scattered, as much as eight or ten miles separating the weather, or easternmost, ships from the lee,208 the flag-ship "Ville de Paris" being among the latter. Anxiety for the "Zélé" kept the French admiral, with the ships in his company, under short canvas, standing to the southward on the port tack (A). The English on the starboard tack, with the wind as they had it,[3] headed east-northeast, and thus, as soon as there was light to see, found the French "broad on the lee bow, and one of M. de Grasse's ships (the "Zélé") towed by a frigate, square under our lee (a), with his bowsprit and foremast prostrate across his forecastle."209 To draw the French farther to leeward, Rodney detached four ships (b) to chase the "Zélé." As soon as De Grasse saw this he signalled his fleet to keep away (c), as Rodney wished, and at the same time to form the line-of-battle, thus calling down to him the ships to windward. The English line was also formed rapidly, and the chasing ships recalled at seven A.M. De Grasse, seeing that if he stood on he would lose the weather-gage altogether, hauled up again on the port tack (c’); and the breeze changing to east-southeast and east in his favor and knocking the English off, the race of the two fleets on opposite tacks, for the advantage of the wind, became nearly equal. The French, however, won, thanks to a superiority in sailing which had enabled them to draw so far to windward of the English on the previous days, and, but for the awkwardness of the "Zélé," might have cleared them altogether (Plate XXI., B). Their leading ships first reached and passed the point where the rapidly converging tracks intersected, while the English leader, the "Marlborough," struck the French line between the sixth and tenth ships (variously stated). The battle, of course, had by this time begun, the ninth ship in the French line, the "Brave," opening fire at twenty minutes before eight A.M. upon the "Marlborough." As there was no previous intention of breaking the line, the English leader kept away, in obedience to a signal from Rodney, and ran close along under the enemy's lee, followed in succession by all the ships as they reached her wake. The battle thus assumed the common and indecisive phase of two fleets passing on opposite tacks, the wind very light, however, and so allowing a more heavy engagement than common under these circumstances, the ships "sliding by" at the rate of three to four knots. Since the hostile lines diverged again south of their point of meeting, De Grasse made signal to keep away four points to south-southwest, thus bringing his van (B, a) to action with the English rear, and not permitting the latter to reach his rear unscathed. There were, however, two dangers threatening the French if they continued their course. Its direction, south or south-southwest, carried them into the calms that hung round the north end of Dominica; and the uncertainty of the wind made it possible that by its hauling to the southward the enemy could pass through their line and gain the wind, and with it the possibility of forcing the decisive battle which the French policy had shunned; and this was in fact what happened. De Grasse therefore made signal at half-past eight to wear together and take the same tack as the English. This, however, was impossible; the two fleets were too close together to admit the evolution. He then signalled to haul close to the wind and wear in succession, which also failed to be done, and at five minutes past nine the dreaded contingency arose; the wind hauled to the southward, knocking off all the French ships that had not yet kept away; that is, all who had English ships close under their lee (Plate XXI. C). Rodney, in the "Formidable," was at this time just drawing up with the fourth ship astern of De Grasse's flag. Luffing to the new wind, he passed through the French line, followed by the five ships next astern of him (C, a), while nearly at the same moment, and from the same causes, his sixth astern (C, b) led through the interval abreast him, followed by the whole English rear. The French line-of-battle was thus broken in two places by columns of enemies' ships in such close order as to force its vessels aside, even if the wind had not conspired to embarrass their action. Every principle upon which a line-of-battle was constituted, for mutual support and for the clear field of fire of each ship, was thus overthrown for the French, and preserved for the English divisions which filed through; and the French were forced off to leeward by the interposition of the enemy's columns, besides being broken up. Compelled thus to forsake the line upon which they had been ranged, it was necessary to re-form upon another, and unite the three groups into which they were divided,—a difficult piece of tactics under any circumstances, but doubly so under the moral impression of disaster, and in presence of a superior enemy, who, though himself disordered, was in better shape, and already felt the glow of victory.

Pl. XXI.

It does not appear that any substantial attempt to re-form was made by the French. To reunite, yes; but only as a flying, disordered mass. The various shifts of wind and movements of the divisions left their fleet, at midday (Plate XXI. D), with the centre (c) two miles northwest of and to leeward of the van (v), the rear (r) yet farther from the centre and to leeward of it. Calms and short puffs of wind prevailed now through both fleets. At half-past one P.M. a light breeze from the east sprang up, and De Grasse made signal to form the line again on the port tack; between three and four, not having succeeded in this, he made signal to form on the starboard tack. The two signals and the general tenor of the accounts show that at no time were the French re-formed after their line was broken; and all the manœuvres tended toward, even if they did not necessitate, taking the whole fleet as far down as the most leewardly of its parts (D). In such a movement, it followed of course that the most crippled ships were left behind, and these were picked up, one by one, by the English, who pursued without any regular order, for which there was no need, as mutual support was assured without it. Shortly after six P.M. De Grasse's flag-ship, the "Ville de Paris," struck her colors to the "Barfleur," carrying the flag of Sir Samuel Hood. The French accounts state that nine of the enemy's ships then surrounded her, and there is no doubt that she had been fought to the bitter end. Her name, commemorating the great city whose gift she had been to the king, her unusual size, and the fact that no French naval commander-in-chief had before been taken prisoner in battle, conspired to bestow a peculiar brilliancy upon Rodney's victory. Four other ships-of-the-line were taken,210 and, singularly enough, upon these particular ships was found the whole train of artillery intended for the reduction of Jamaica.

Such were the leading features of the Battle of the Saints, or, as it is sometimes styled, of the 12th of April, known to the French as the Battle of Dominica. Certain points which have so far been omitted for the sake of clearness, but which affect the issue, must now be given. When the day opened, the French fleet was greatly scattered and without order.211 De Grasse, under the influence of his fears for the "Zélé," so precipitated his movements that his line was not properly formed at the moment of engaging. The van ships had not yet come into position (B, a), and the remainder were so far from having reached their places that De Vaudreuil, commanding the rear division and last engaged, states that the line was formed under the fire of musketry. The English, on the contrary, were in good order, the only change made being to shorten the interval between ships from two to one cable's length (seven hundred feet). The celebrated stroke of breaking through the French line was due, not to previous intention, but to a shift of wind throwing their ships out of order and so increasing the spaces between them; while the gap through which Rodney's group penetrated was widened by the "Diadème" on its north side being taken aback and paying round on the other tack (C, c.) Sir Charles Douglas says the immediate effect, where the flag-ship broke through, was "the bringing together, almost if not quite in contact with each other, the four ships of the enemy which were nearest," on the north, "to the point alluded to (c), and coming up in succession. This unfortunate group, composing now only one large single object at which to fire, was attacked by the "Duke," "Namur," and "Formidable" (ninety-gun ships) all at once, receiving several broadsides from each, not a single shot missing; and great must have been the slaughter." The "Duke" (C, d), being next ahead of the flag-ship, had followed her leader under the French lee; but as soon as her captain saw that the "Formidable" had traversed the enemy's order, he did the same, passing north of this confused group and so bringing it under a fire from both sides. The log of the "Magnanime," one of the group, mentions passing under the fire of two three-deckers, one on either side.

As soon as the order was thus broken, Rodney hauled down the signal for the line, keeping flying that for close action, and at the same time ordered his van, which had now passed beyond and north of the enemy's rear, to go about and rejoin the English centre. This was greatly delayed through the injuries to spars and sails received in passing under the enemy's fire. His own flag-ship and the ships with her went about. The rear, under Hood, instead of keeping north again to join the centre, stood to windward for a time, and were then becalmed at a considerable distance from the rest of the fleet.

Much discussion took place at a later day as to the wisdom of Rodney's action in breaking through his enemy's order, and to whom the credit, if any, should be ascribed. The latter point is of little concern; but it may be said that the son of Sir Charles Douglas, Rodney's chief-of-staff, brought forward an amount of positive evidence, the only kind that could be accepted to diminish the credit of the person wholly responsible for the results, which proves that the suggestion came from Douglas, and Rodney's consent was with difficulty obtained. The value of the manœuvre itself is of more consequence than any question of personal reputation. It has been argued by some that, so far from being a meritorious act, it was unfortunate, and for Rodney's credit should rather be attributed to the force of circumstances than to choice. It had been better, these say, to have continued along under the lee of the French rear, thus inflicting upon it the fire of the whole English line, and that the latter should have tacked and doubled on the French rear. This argument conveniently forgets that tacking, or turning round in any way, after a brush of this kind, was possible to only a part of the ships engaged; and that these would have much difficulty in overtaking the enemies who had passed on, unless the latter were very seriously crippled. Therefore this suggested attack, the precise reproduction of the battle of Ushant, really reduces itself to the fleets passing on opposite tacks, each distributing its fire over the whole of the enemy's line without attempting any concentration on a part of it. It may, and must, be conceded at once, that Rodney's change of course permitted the eleven rear ships of the French (D, r) to run off to leeward, having received the fire of only part of their enemy, while the English van had undergone that of nearly the whole French fleet. These ships, however, were thus thrown entirely out of action for a measurable and important time by being driven to leeward, and would have been still more out of position to help any of their fleet, had not De Grasse himself been sent to leeward by Hood's division cutting the line three ships ahead of him. The thirteen leading French ships, obeying the last signal they had seen, were hugging the wind; the group of six with De Grasse (C, e) would have done the same had they not been headed off by Hood's division. The result of Rodney's own action alone, therefore, would have been to divide the French fleet into two parts, separated by a space of six miles, and one of them hopelessly to leeward. The English, having gained the wind, would have been in position easily to "contain" the eleven lee ships, and to surround the nineteen weather ones in overwhelming force. The actual condition, owing to the two breaches in the line, was slightly different; the group of six with De Grasse being placed between his weather and lee divisions, two miles from the former, four from the latter (D). It seems scarcely necessary to insist upon the tactical advantages of such a situation for the English, even disregarding the moral effect of the confusion through which the French had passed. In addition to this, a very striking lesson is deducible from the immediate effects of the English guns in passing through. Of the five ships taken, three were those under whose sterns the English divisions pierced.212 Instead of giving and taking, as the parallel lines ran by, on equal terms, each ship having the support of those ahead and astern, the French ships near which the penetrating columns passed received each the successive fire of all the enemy's division. Thus Hood's thirteen ships filed by the two rear ones of the French van, the "César" and "Hector," fairly crushing them under this concentration of fire; while in like manner, and with like results, Rodney's six passed by the "Glorieux." This "concentration by defiling" past the extremity of a column corresponds quite accurately to the concentration upon the flank of a line, and has a special interest, because if successfully carried out it would be as powerful an attack now as it ever has been. If quick to seize their advantage, the English might have fired upon the ships on both sides of the gaps through which they passed, as the "Formidable" actually did; but they were using the starboard broadsides, and many doubtless did not realize their opportunity until too late. The natural results of Rodney's act, therefore, were: (1) The gain of the wind, with the power of offensive action; (2) Concentration of fire upon a part of the enemy's order; and (3) The introduction into the latter of confusion and division, which might, and did, become very great, offering the opportunity of further tactical advantage. It is not a valid reply to say that, had the French been more apt, they could have united sooner. A manœuvre that presents a good chance of advantage does not lose its merit because it can be met by a prompt movement of the enemy, any more than a particular lunge of the sword becomes worthless because it has its appropriate parry. The chances were that by heading off the rear ships, while the van stood on, the French fleet would be badly divided; and the move was none the less sagacious because the two fragments could have united sooner than they did, had they been well handled. With the alternative action suggested, of tacking after passing the enemy's rear, the pursuit became a stern chase, in which both parties having been equally engaged would presumably be equally crippled. Signals of disability, in fact, were numerous in both fleets.

Independently of the tactical handling of the two fleets, there were certain differences of equipment which conferred tactical advantage, and are therefore worth noting. The French appear to have had finer ships, and, class for class, heavier armaments. Sir Charles Douglas, an eminent officer of active and ingenious turn of mind, who paid particular attention to gunnery details, estimated that in weight of battery the thirty-three French were superior to the thirty-six English by the force of four 84-gun ships; and that after the loss of the "Zélé," "Jason," and "Caton" there still remained an advantage equal to two seventy-fours. The French admiral La Gravière admits the generally heavier calibre of French cannon at this era. The better construction of the French ships and their greater draught caused them to sail and beat better, and accounts in part for the success of De Grasse in gaining to windward; for in the afternoon of the 11th only three or four of the body of his fleet were visible from the mast-head of the English flag-ship, which had been within gunshot of them on the 9th. It was the awkwardness of the unlucky "Zélé" and of the "Magnanime," which drew down De Grasse from his position of vantage, and justified Rodney's perseverance in relying upon the chapter of accidents to effect his purpose. The greater speed of the French as a body is somewhat hard to account for, because, though undoubtedly with far better lines, the practice of coppering the bottom had not become so general in France as in England, and among the French there were several uncoppered and worm-eaten ships.213 The better sailing of the French was, however, remarked by the English officers, though the great gain mentioned must have been in part owing to Rodney's lying-by, after the action of the 9th, to refit, due probably to the greater injury received by the small body of his vessels, which had been warmly engaged, with greatly superior numbers. It was stated, in narrating that action, that the French kept at half cannon-range; this was to neutralize a tactical advantage the English had in the large number of carronades and other guns of light weight but large calibre, which in close action told heavily, but were useless at greater distances. The second in command, De Vaudreuil, to whom was intrusted the conduct of that attack, expressly states that if he had come within reach of the carronades his ships would have been quickly unrigged. Whatever judgment is passed upon the military policy of refusing to crush an enemy situated as the English division was, there can be no question that, if the object was to prevent pursuit, the tactics of De Vaudreuil on the 9th was in all respects excellent. He inflicted the utmost injury with the least exposure of his own force. On the 12th, De Grasse, by allowing himself to be lured within reach of carronades, yielded this advantage, besides sacrificing to an impulse his whole previous strategic policy. Rapidly handled from their lightness, firing grape and shot of large diameter, these guns were peculiarly harmful in close action and useless at long range. In a later despatch De Vaudreuil says: "The effect of these new arms is most deadly within musket range; it is they which so badly crippled us on the 12th of April." There were other gunnery innovations, in some at least of the English ships, which by increasing the accuracy, the rapidity, and the field of fire, greatly augmented the power of their batteries. These were the introduction of locks, by which the man who aimed also fired; and the fitting to the gun-carriages of breast-pieces and sweeps, so that the guns could be pointed farther ahead or astern,—that is, over a larger field than had been usual. In fights between single ships, not controlled in their movements by their relations to a fleet, this improvement would at times allow the possessor to take a position whence he could train upon his enemy without the latter being able to reply, and some striking instances of such tactical advantage are given. In a fleet fight, such as is now being considered, the gain was that the guns could be brought to bear farther forward, and could follow the opponent longer as he passed astern, thus doubling, or more, the number of shots he might receive, and lessening for him the interval of immunity enjoyed between two successive antagonists.214 These matters of antiquated and now obsolete detail carry with them lessons that are never obsolete; they differ in no respect from the more modern experiences with the needle-gun and the torpedo.

And indeed this whole action of April 12, 1782, is fraught with sound military teaching. Perseverance in pursuit, gaining advantage of position, concentration of one's own effort, dispersal of the enemy's force, the efficient tactical bearing of small but important improvements in the material of war, have been dwelt on. To insist further upon the necessity of not letting slip a chance to beat the enemy in detail, would be thrown away on any one not already convinced by the bearing of April 9 on April 12. The abandonment of the attack upon Jamaica, after the defeat of the French fleet, shows conclusively that the true way to secure ulterior objects is to defeat the force which threatens them. There remains at least one criticism, delicate in its character, but essential to draw out the full teachings of these events; that is, upon the manner in which the victory was followed up, and the consequent effects upon the war in general.

The liability of sailing-ships to injury in spars and sails, in other words, in that mobility which is the prime characteristic of naval strength, makes it difficult to say, after a lapse of time, what might or might not have been done. It is not only a question of actual damage received, which log-books may record, but also of the means for repair, the energy and aptitude of the officers and seamen, which differ from ship to ship. As to the ability of the English fleet, however, to follow up its advantages by a more vigorous pursuit on the 12th of April, we have the authority of two most distinguished officers,—Sir Samuel Hood, the second in command, and Sir Charles Douglas, the captain of the fleet, or chief-of-staff to the admiral. The former expressed the opinion that twenty ships might have been taken, and said so to Rodney the next day; while the chief-of-staff was so much mortified by the failure, and by the manner in which the admiral received his suggestions, as seriously to contemplate resigning his position.215

Advice and criticism are easy, nor can the full weight of a responsibility be felt, except by the man on whom it is laid; but great results cannot often be reached in war without risk and effort. The accuracy of the judgment of these two officers, however, is confirmed by inference from the French reports. Rodney justifies his failure to pursue by alleging the crippled condition of many ships, and other matters incident to the conclusion of a hard-fought battle, and then goes on to suggest what might have been done that night, had he pursued, by the French fleet, which "went off in a body of twenty-six ships-of-the-line."216 These possibilities are rather creditable to his imagination, considering what the French fleet had done by day; but as regards the body of twenty-six217 ships, De Vaudreuil, who, after De Grasse's surrender, made the signal for the ships to rally round his flag, found only ten with him next morning, and was not joined by any more before the 14th. During the following days five more joined him at intervals.218 With these he went to the rendezvous at Cap Français, where he found others, bringing the whole number who repaired thither to twenty. The five remaining, of those that had been in the action, fled to Curaçoa, six hundred miles distant, and did not rejoin until May. The "body of twenty-six ships," therefore, had no existence in fact; on the contrary, the French fleet was very badly broken up, and several of its ships isolated. As regards the crippled condition, there seems no reason to think the English had suffered more, but rather less, than their enemy; and a curious statement, bearing upon this, appears in a letter from Sir Gilbert Blane:—

"It was with difficulty we could make the French officers believe that the returns of killed and wounded, made by our ships to the admiral, were true; and one of them flatly contradicted me, saying we always gave the world a false account of our loss. I then walked with him over the decks of the 'Formidable,' and bid him remark what number of shot-holes there were, and also how little her rigging had suffered, and asked if that degree of damage was likely to be connected with the loss of more than fourteen men, which was our number killed, and the greatest of any in the fleet, except the 'Royal Oak' and 'Monarch.' He … owned our fire must have been much better kept up and directed than theirs."219