полная версия

полная версияThe Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783

During his four months absence the failure of Bussy to appear with his troops, and the arrival of Bickerton, who had shown himself on both coasts, had seriously injured the French cause. The treaty of peace between the English and the Mahrattas had been ratified; and the former, released from this war and reinforced, had attacked the sultan on the west, or Malabar, coast. The effect of this diversion was of course felt on the east coast, despite the efforts of the French to keep the new sultan there. The sickness among the troops at the Isle of France had, however, ceased early in November; and had Bussy then started without delay, he and Suffren would now have met in the Carnatic, with full command of the sea and large odds in their favor ashore. Hughes did not arrive till two months later.

Being thus alone, Suffren, after communicating with Tippoo-Saib, the new sultan of Mysore, went to Trincomalee; and there he was at last joined, on the 10th of March, by Bussy, accompanied by three ships-of-the-line and numerous transports. Eager to bring the troops into the field, Suffren sailed on the 15th with his fastest ships, and landed them the next day at Porto Novo. He returned to Trincomalee on the 11th of April, and fell in with Hughes's fleet of seventeen ships-of-the-line off the harbor's mouth. Having only part of his force with him, no fight ensued, and the English went on to Madras. The southwest monsoon was now blowing.

It is not necessary to follow the trivial operations of the next two months. Tippoo being engaged on the other side of the peninsula and Bussy displaying little vigor, while Hughes was in superior force off the coast, the affairs of the French on shore went from bad to worse. Suffren, having but fifteen ships to eighteen English, was unwilling to go to leeward of Trincomalee, lest it should fall before he could return to it. Under these conditions the English troops advanced from Madras, passing near but around Cuddalore, and encamped to the southward of it, by the sea. The supply-ships and light cruisers were stationed off the shore near the army; while Admiral Hughes, with the heavy ships, anchored some twenty miles south, where, being to windward, he covered the others.

In order to assure to Suffren the full credit of his subsequent course, it is necessary to emphasize the fact that Bussy, though commander-in-chief both by land and sea, did not venture to order him to leave Trincomalee and come to his support. Allowing him to feel the extremity of the danger, he told him not to leave port unless he heard that the army was shut up in Cuddalore, and blockaded by the English squadron. This letter was received on the 10th of June. Suffren waited for no more. The next day he sailed, and forty-eight hours later his frigates saw the English fleet. The same day, the 13th, after a sharp action, the French army was shut up in the town, behind very weak walls. Everything now depended on the action of the fleets.

Upon Suffren's appearance, Hughes moved away and anchored four or five miles from the town. Baffling winds prevailed for three days; but the monsoon resuming on the 16th, Suffren approached. The English admiral not liking to accept action at anchor, and to leeward, in which he was right, got under way; but attaching more importance to the weather-gage than to preventing a junction between the enemy's land and sea forces, he stood out into the offing with a southerly, or south-southeast wind, notwithstanding his superior numbers. Suffren formed on the same tack, and some manœuvring ensued during that night and the next day. At eight P.M. of the 17th the French squadron, which had refused to be drawn to sea, anchored off Cuddalore and communicated with the commander-in-chief. Twelve hundred of the garrison were hastily embarked to fill the numerous vacancies at the guns of the fleet.

Until the 20th the wind, holding unexpectedly at west, denied Hughes the advantage which he sought; and finally on that day he decided to accept action and await the attack. It was made by Suffren with fifteen ships to eighteen, the fire opening at quarter-past four P.M. and lasting until half-past six. The loss on both sides was nearly equal; but the English ships, abandoning both the field of battle and their army, returned to Madras. Suffren anchored before Cuddalore.

The embarrassment of the British army was now very great. The supply-ships on which it had depended fled before the action of the 20th, and the result of course made it impossible for them to return. The sultan's light cavalry harassed their communications by land. On the 25th, the general commanding wrote that his "mind was on the rack without a moment's rest since the departure of the fleet, considering the character of M. de Suffren, and the infinite superiority on the part of the French now that we are left to ourselves." From this anxiety he was relieved by the news of the conclusion of peace, which reached Cuddalore on the 29th by flag-of-truce from Madras.

If any doubt had remained as to the relative merits of the two sea-commanders, the last few days of their campaign would have removed them. Hughes alleges the number of his sick and shortness of water as his reasons for abandoning the contest. Suffren's difficulties, however, were as great as his own;192 and if he had an advantage at Trincomalee, that only shifts the dispute a step back, for he owed its possession to superior generalship and activity. The simple facts that with fifteen ships he forced eighteen to abandon a blockade, relieved the invested army, strengthened his own crews, and fought a decisive action, make an impression which does not need to be diminished in the interests of truth.193 It is probable that Hughes's self-reliance had been badly shaken by his various meetings with Suffren.

Although the tidings of peace sent by Hughes to Bussy rested only upon unofficial letters, they were too positive to justify a continuance of bloodshed. An arrangement was entered into by the authorities of the two nations in India, and hostilities ceased on the 8th of July. Two months later, at Pondicherry, the official despatches reached Suffren. His own words upon them are worth quoting, for they show the depressing convictions under which he had acted so noble a part: "God be praised for the peace! for it was clear that in India, though we had the means to impose the law, all would have been lost. I await your orders with impatience, and heartily pray they may permit me to leave. War alone can make bearable the weariness of certain things."

On the 6th of October, 1783, Suffren finally sailed from Trincomalee for France, stopping at the Isle of France and the Cape of Good Hope. The homeward voyage was a continued and spontaneous ovation. In each port visited the most flattering attentions were paid by men of every degree and of every nation. What especially gratified him was the homage of the English captains. It might well be so; none had so clearly established a right to his esteem as a warrior. On no occasion when Hughes and Suffren met, save the last, did the English number over twelve ships; but six English captains had laid down their lives, obstinately opposing his efforts. While he was at the Cape, a division of nine of Hughes's ships, returning from the war, anchored in the harbor. Their captains called eagerly upon the admiral, the stout Commodore King of the "Exeter" at their head. "The good Dutchmen have received me as their savior," wrote Suffren; "but among the tributes which have most flattered me, none has given me more pleasure than the esteem and consideration testified by the English who are here." On reaching home, rewards were heaped upon him. Having left France as a captain, he came back a rear-admiral; and immediately after his return the king created a fourth vice-admiralship, a special post to be filled by Suffren, and to lapse at his death. These honors were won by himself alone; they were the tribute paid to his unyielding energy and genius, shown not only in actual fight but in the steadfastness which held to his station through every discouragement, and rose equal to every demand made by recurring want and misfortune.

Alike in the general conduct of his operations and on the battlefield under the fire of the enemy, this lofty resolve was the distinguishing merit of Suffren; and when there is coupled with it the clear and absolute conviction which he held of the necessity to seek and crush the enemy's fleet, we have probably the leading traits of his military character. The latter was the light that led him, the former the spirit that sustained him. As a tactician, in the sense of a driller of ships, imparting to them uniformity of action and manœuvring, he seems to have been deficient, and would probably himself have admitted, with some contempt, the justice of the criticism made upon him in these respects. Whether or no he ever actually characterized tactics—meaning thereby elementary or evolutionary tactics—as the veil of timidity, there was that in his actions which makes the mot probable. Such a contempt, however, is unsafe even in the case of genius. The faculty of moving together with uniformity and precision is too necessary to the development of the full power of a body of ships to be lightly esteemed; it is essential to that concentration of effort at which Suffren rightly aimed, but which he was not always careful to secure by previous dispositions. Paradoxical though it sounds, it is true that only fleets which are able to perform regular movements can afford at times to cast them aside; only captains whom the habit of the drill-ground has familiarized with the shifting phases it presents, can be expected to seize readily the opportunities for independent action presented by the field of battle. Howe and Jervis must make ready the way for the successes of Nelson. Suffren expected too much of his captains. He had the right to expect more than he got, but not that ready perception of the situation and that firmness of nerve which, except to a few favorites of Nature, are the result only of practice and experience.

Still, he was a very great man. When every deduction has been made, there must still remain his heroic constancy, his fearlessness of responsibility as of danger, the rapidity of his action, and the genius whose unerring intuition led him to break through the traditions of his service and assert for the navy that principal part which befits it, that offensive action which secures the control of the sea by the destruction of the enemy's fleet. Had he met in his lieutenants such ready instruments as Nelson found prepared for him, there can be little doubt that Hughes's squadron would have been destroyed while inferior to Suffren's, before reinforcements could have arrived; and with the English fleet it could scarcely have failed that the Coromandel coast also would have fallen. What effect this would have had upon the fate of the peninsula, or upon the terms of the peace, can only be surmised. His own hope was that, by acquiring the superiority in India, a glorious peace might result.

No further opportunities of distinction in war were given to Suffren. The remaining years of his life were spent in honored positions ashore. In 1788, upon an appearance of trouble with England, he was appointed to the command of a great fleet arming at Brest; but before he could leave Paris he died suddenly on the 8th of December, in the sixtieth year of his age. There seems to have been no suspicion at the time of other than natural causes of death, he being exceedingly stout and of apoplectic temperament; but many years after a story, apparently well-founded, became current that he was killed in a duel arising out of his official action in India. His old antagonist on the battlefield, Sir Edward Hughes, died at a great age in 1794.

CHAPTER XIII

Events in the West Indies after the Surrender of Yorktown—Encounters of De Grasse with Hood.—The Sea Battle of the Saints.—1781, 1782.

The surrender of Cornwallis marked the end of the active war upon the American continent. The issue of the struggle was indeed assured upon the day when France devoted her sea power to the support of the colonists; but, as not uncommonly happens, the determining characteristics of a period were summed up in one striking event. From the beginning, the military question, owing to the physical characteristics of the country, a long seaboard with estuaries penetrating deep into the interior, and the consequent greater ease of movement by water than by land, had hinged upon the control of the sea and the use made of that control. Its misdirection by Sir William Howe in 1777, when he moved his army to the Chesapeake instead of supporting Burgoyne's advance, opened the way to the startling success at Saratoga, when amazed Europe saw six thousand regular troops surrendering to a body of provincials. During the four years that followed, until the surrender of Yorktown, the scales rose and fell according as the one navy or the other appeared on the scene, or as English commanders kept touch with the sea or pushed their operations far from its support. Finally, at the great crisis, all is found depending upon the question whether the French or the English fleet should first appear, and upon their relative force.

The maritime struggle was at once transferred to the West Indies. The events which followed there were antecedent in time both to Suffren's battles and to the final relief of Gibraltar; but they stand so much by themselves as to call for separate treatment, and have such close relation to the conclusion of the war and the conditions of peace, as to form the dramatic finale of the one and the stepping-stone of transition to the other. It is fitting indeed that a brilliant though indecisive naval victory should close the story of an essentially naval war.

The capitulation of Yorktown was completed on the 19th of October, 1781, and on the 5th of November, De Grasse, resisting the suggestions of Lafayette and Washington that the fleet should aid in carrying the war farther south, sailed from the Chesapeake. He reached Martinique on the 26th, the day after the Marquis de Bouillé, commanding the French troops in the West Indies, had regained by a bold surprise the Dutch island of St. Eustatius. The two commanders now concerted a joint expedition against Barbadoes, which was frustrated by the violence of the trade winds.

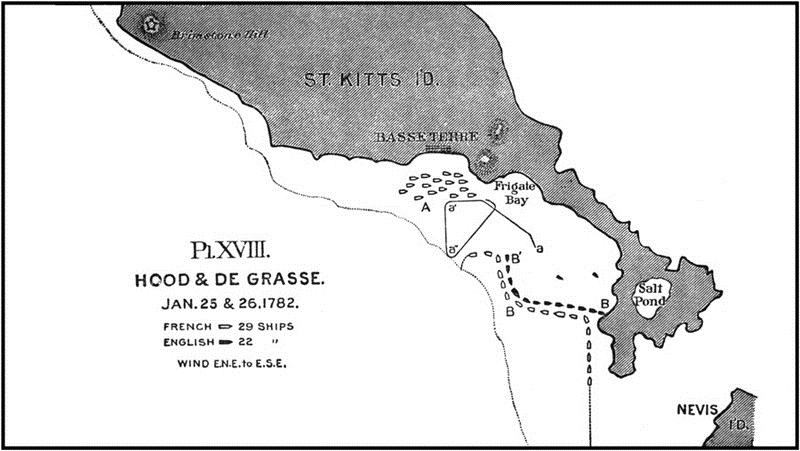

Foiled here, the French proceeded against the island of St. Christopher, or St. Kitt's (Plate XVIII.). On the 11th of January, 1782, the fleet, carrying six thousand troops, anchored on the west coast off Basse Terre, the chief town. No opposition was met, the small garrison of six hundred men retiring to a fortified post ten miles to the northwest, on Brimstone Hill, a solitary precipitous height overlooking the lee shore of the island. The French troops landed and pursued, but the position being found too strong for assault, siege operations were begun.

The French fleet remained at anchor in Basse Terre road. Meanwhile, news of the attack was carried to Sir Samuel Hood, who had followed De Grasse from the continent, and, in the continued absence of Rodney, was naval commander-in-chief on the station. He sailed from Barbadoes on the 14th, anchored at Antigua on the 21st, and there embarked all the troops that could be spared,—about seven hundred men. On the afternoon of the 23d the fleet started for St. Kitt's, carrying such sail as would bring it within striking distance of the enemy at daylight next morning.

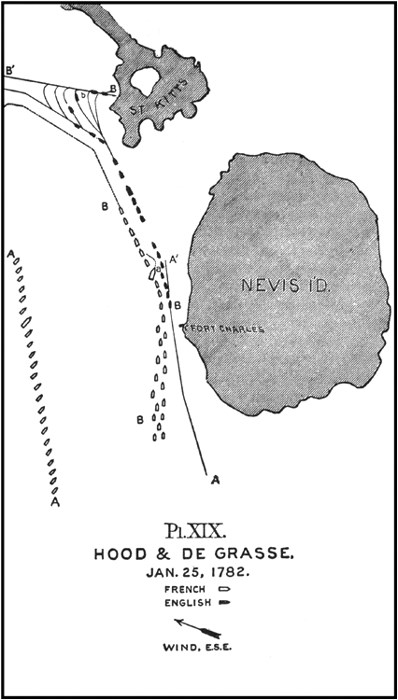

The English having but twenty-two ships to the French twenty-nine, and the latter being generally superior in force, class for class, it is necessary to mark closely the lay of the land in order to understand Hood's original plans and their subsequent modifications; for, resultless as his attempt proved, his conduct during the next three weeks forms the most brilliant military effort of the whole war. The islands of St. Kitt's and Nevis (Plates XVIII. and XIX.) being separated only by a narrow channel, impracticable for ships-of-the-line, are in effect one, and their common axis lying northwest and southeast, it is necessary for sailing-ships, with the trade wind, to round the southern extremity of Nevis, from which position the wind is fair to reach all anchorages on the lee side of the islands. Basse Terre is about twelve miles distant from the western point of Nevis (Fort Charles), and its roadstead lies east and west. The French fleet were anchored there in disorder (Plate XVIII., A), three or four deep, not expecting attack, and the ships at the west end of the road could not reach those at the east without beating to windward,—a tedious, and under fire a perilous process. A further most important point to note is that all the eastern ships were so placed that vessels approaching from the southward could reach them with the usual wind.

Hood, therefore, we are told, intended to appear at early daylight, in order of and ready for battle, and fall upon the eastern ships, filing by them with his whole fleet (a, a’), thus concentrating the fire of all upon a few of the enemy; then turning away, so as to escape the guns of the others, he proposed, first wearing and then tacking, to keep his fleet circling in long procession (a’, a’’) past that part of the enemy's ships chosen for attack. The plan was audacious, but undeniably sound in principle; some good could hardly fail to follow, and unless De Grasse showed more readiness than he had hitherto done, even decisive results might be hoped for.194

Pl. XVIII.

The best-laid plans, however, may fail, and Hood's was balked by the awkwardness of a lieutenant of the watch, who hove-to (stopped) a frigate at night ahead of the fleet, and was consequently run down by a ship-of-the-line. The latter also received such injury as delayed the movement, several hours being lost in repairing damages. The French were thus warned of the enemy's approach, and although not suspecting his intention to attack, De Grasse feared that Hood would pass down to leeward of him and disturb the siege of Brimstone Hill,—an undertaking so rash for an inferior force that it is as difficult to conceive how he could have supposed it, as to account for his overlooking the weakness of his own position at anchor.

At one P.M. of the 24th the English fleet was seen rounding the south end of Nevis; at three De Grasse got under way and stood to the southward. Toward sundown Hood also went about and stood south, as though retreating; but he was well to windward of his opponent, and maintained this advantage through the night. At daybreak both fleets were to leeward of Nevis,—the English near the island, the French about nine miles distant (Plate XIX.). Some time was spent in manœuvring, with the object on Hood's part of getting the French admiral yet more to leeward; for, having failed in his first attempt, he had formed the yet bolder intention of seizing the anchorage his unskilful opponent had left, and establishing himself there in an impregnable manner. In this he succeeded, as will be shown; but to understand the justification for a movement confessedly hazardous, it must be pointed out that he thus would place himself between the besiegers of Brimstone Hill and their fleet; or if the latter anchored near the hill, the English fleet would be between it and its base in Martinique, ready to intercept supplies or detachments approaching from the southward. In short, the position in which Hood hoped to establish himself was on the flank of the enemy's communications, a position the more advantageous because the island alone could not long support the large body of troops so suddenly thrown upon it. Moreover, both fleets were expecting reinforcements; Rodney was on his way and might arrive first, which he did, and in time to save St. Kitt's, which he did not. It was also but four months since Yorktown; the affairs of England were going badly; something must be done, something left to chance, and Hood knew himself and his officers. It may be added that he knew his opponent.

At noon, when the hillsides of Nevis were covered with expectant and interested sightseers, the English fleet rapidly formed its line on the starboard tack and headed north for Basse Terre (Plate XIX., A, A’). The French, at the moment, were in column steering south, but went about at once and stood for the enemy in a bow-and-quarter line195 (A, A). At two the British had got far enough for Hood to make signal to anchor. At twenty minutes past two the van of the French came within gunshot of the English centre (B, B, B), and shortly afterward the firing began, the assailants very properly directing their main effort upon the English rear ships, which, as happens with most long columns, had opened out, a tendency increased in this case by the slowness of the fourth ship from the rear, the "Prudent." The French flag-ship, "Ville de Paris," of one hundred and twenty guns, bearing De Grasse's flag, pushed for the gap thus made, but was foiled by the "Canada," seventy-four, whose captain, Cornwallis, the brother of Lord Cornwallis, threw all his sails aback, and dropped down in front of the huge enemy to the support of the rear,—an example nobly followed by the "Resolution" and the "Bedford" immediately ahead of him (a). The scene was now varied and animated in the extreme. The English van, which had escaped attack, was rapidly anchoring (b) in its appointed position. The commander-in-chief in the centre, proudly reliant upon the skill and conduct of his captains, made signal for the ships ahead to carry a press of sail, and gain their positions regardless of the danger to the threatened rear. The latter, closely pressed and outnumbered, stood on unswervingly, shortened sail, and came to anchor, one by one, in a line ahead (B, B’), under the roar of the guns of their baffled enemies. The latter filed by, delivered their fire, and bore off again to the southward, leaving their former berths to their weaker but clever antagonists.

Pl. XIX.

The anchorage thus brilliantly taken by Hood was not exactly the same as that held by De Grasse the day before; but as it covered and controlled it, his claim that he took up the place the other had left is substantially correct. The following night and morning were spent in changing and strengthening the order, which was finally established as follows (Plate XVIII., B, B’). The van ship was anchored about four miles southeast from Basse Terre, so close to the shore that a ship could not pass inside her, nor, with the prevailing wind, even reach her, because of a point and shoal just outside, covering her position. From this point the line extended in a west-northwest direction to the twelfth or thirteenth ship (from a mile and a quarter to a mile and a half), where it turned gradually but rapidly to north, the last six ships being on a north and south line. Hood's flag-ship, the "Barfleur," of ninety guns, was at the apex of the salient angle thus formed.

It would not have been impossible for the French fleet to take the anchorage they formerly held; but it and all others to leeward were forbidden by the considerations already stated, so long as Hood remained where he was. It became necessary therefore to dislodge him, but this was rendered exceedingly difficult by the careful tactical dispositions that have been described. His left flank was covered by the shore. Any attempt to enfilade his front by passing along the other flank was met by the broadsides of the six or eight ships drawn up en potence to the rear. The front commanded the approaches to Basse Terre. To attack him in the rear, from the northwest, was forbidden by the trade-wind. To these difficulties was to be added that the attack must be made under sail against ships at anchor, to whom loss of spars would be of no immediate concern; and which, having springs196 out, could train their broadsides over a large area with great ease.

Nevertheless, both sound policy and mortification impelled De Grasse to fight, which he did the next day, January 26. The method of attack, in single column of twenty-nine ships against a line so carefully arranged, was faulty in the extreme; but it may be doubted whether any commander of that day would have broken through the traditional fighting order.197 Hood had intended the same, but he hoped a surprise on an ill-ordered enemy, and at the original French anchorage it was possible to reach their eastern ships, with but slight exposure to concentrated fire. Not so now. The French formed to the southward and steered for the eastern flank of Hood's line. As their van ship drew up with the point already mentioned, the wind headed her, so that she could only reach the third in the English order, the first four ships of which, using their springs, concentrated their guns upon her. This vessel was supposed by the English to be the "Pluton," and if so, her captain was D'Albert de Rions, in Suffren's opinion the foremost officer of the French navy. "The crash occasioned by their destructive broadsides," wrote an English officer who was present, "was so tremendous that whole pieces of plank were seen flying from her off side ere she could escape the cool, concentrated fire of her determined adversaries. As she proceeded along the British line, she received the first fire of every ship in passing. She was indeed in so shattered a state as to be compelled to bear away for St. Eustatius." And so ship after ship passed by, running the length of the line (Plate XVIII., B, B), distributing their successive fires in gallant but dreary, ineffectual monotony over the whole extent. A second time that day De Grasse attacked in the same order, but neglecting the English van, directed his effort upon the rear and centre. This was equally fruitless, and seems to have been done with little spirit.