полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 63, No. 391, May, 1848

Mr Lingen reports as follows of a school in the parish of Llangwnnor, Carmarthenshire.

"I visited this school on the 24th of November; it is held in a ruinous hovel of the most squalid and miserable character, which was originally erected by the parish, but apparently by encroachment. On Sunday the Calvinistic Methodists hold a school in it; the floor is of bare earth, full of deep holes; the windows are all broken; a tattered partition of lath and plaster divides it into two unequal portions; in the larger were a few wretched benches, and a small desk for the master in one corner; in the lesser was an old door with the hasp still upon it, laid crossways upon two benches, about half a yard high, to serve for a writing-desk! Such of the scholars as write retire in pairs to this part of the room, and kneel on the ground while they write. On the floor was a heap of loose coal, and a litter of straw, paper, and all kinds of rubbish. The vicar's son informed me that he had seen eighty children in this hut. In summer the heat of it is said to be suffocating; and no wonder.

"The master appeared a pains-taking and amiable man, and had a very good character given of him. He had been disabled from following his trade (that of a carpenter) by an accident. He was but indifferently acquainted with English; one of the copies set by him was 'The Jews slain Christ.' I stood by while he heard two classes – one of two little girls, and another of three little boys and a girl – read. The two first read an account of our Lord's temptation; the master asked them to spell a few words, which they did, and then to give the Welsh equivalents for several English words, which they also did; he asked no other questions. The other class read small sentences containing a repetition of the same word, e. g., 'The bad do sin – wo to the bad – the bad do lie,' &c. They were utterly unable to turn such sentences into Welsh; they knew the letters (for they could point to particular words when required,) and they knew to some extent the English sound of them; they knew also the meaning of the single words (for they could give the Welsh equivalents,) but they had no idea of the sentence. With them, therefore, English reading must be (at best) a mere string of words, connected only by juxtaposition."

Mr. Symons gives the following report of a school at Llanfihangel Creiddyn, in Cardiganshire.

"This parish contains a very good modern school-room, but it is not finished inside. There is no floor of any sort. The school, nevertheless, is of the most inferior description, devoid of method in the instruction, and of capacity in the master. During the whole of last summer the school was shut, and the room was used by the carpenters who were repairing the church. One of their benches is now used as a writing table. Few of the children remain a year; they come for a quarter or half-a-year, and then leave the school. Fourteen children were present, together with two young men who were there to learn writing. Four of the children only could read in the Testament, and the master selected the 1st chapter of Revelation for them to read in. They stammered through several verses, mispronouncing nearly every word, and which the master took some pains to correct. None of them knew the meaning, or could give the Welsh words for 'show,' 'gave,' or 'faith.' One or two only knew that of 'grace,' 'woman,' 'nurse.' Their knowledge of spelling was very limited. Of Scripture they knew next to nothing. Jesus was said to be the son of Joseph; one child only said the Son of God; another thought he was on earth now; and another said he would come again 'to increase grace,' grace meaning godliness. Three out of the five could not tell why Christ came to the earth, a penny having been offered for a correct answer. Two could not tell any one thing that Christ did, and a third said he drew water from a rock in the land of Canaan. None knew the number of the Apostles; one never heard of them, and two could not name any of them. Christ died in Calvary, which one said was in England, and the others did not know where it was. Four could not tell the day Christ was born, or what it was called. The days of a week were guessed to be five, six, four, and seven. The days in the month twenty and fifteen, and nine could name the months. None knew the number of days in the year; and all thought the sun moved round the world. This country was said to be Cardiganshire, not Wales. Ireland one thought a town, and another a parish. England was a town, and London a country. A king was a reasonable being (creadwr rhesymnol.) Victoria is the Queen, and it is our duty to do every thing for her. In arithmetic they could do next to nothing, and failed to answer the simplest questions. I then examined the young men, promising two-pence to those who answered most correctly. They had a notion of the elements of Scripture truths. Two of them had no notion of arithmetic. The third answered easy questions, and could do sums in the simple rules. On general subjects their information was very little superior to that of the children."

And Mr Vaughan Johnson, in examining the church school of Holyhead, in the Isle of Anglesey, reports as follows: —

"Holyhead Church School.– A school for boys and girls, taught by a master and mistress, in separate rooms of a large building set apart for that purpose. Number of boys, 96; of girls, 47; 10 monitors are employed. Subjects taught, reading, writing, and arithmetic, the Holy Scriptures and Church catechism. Fees, 1d. per week.

"This school was examined November 9. Total number present, 117. Of these, 20 could write well on paper; 40 were able to read with ease; and 22 could repeat the Church catechism, 15 of them with accuracy. In knowledge of Holy Scripture and in arithmetic, the boys were very deficient. Scholars in the first class said that there were 18 gospels, that Bartholomew wrote one and Simon another; that Moses was the son of David. These answers were not corrected by the rest. By a lower class it was said, that Jerusalem is in heaven, and that St Paul wrote the gospel according to St Matthew; another believed it was written by Jesus Christ. The oldest boy in a large class said, that Joseph was the son of Abraham. A child about 10 years old said, that Jesus Christ was the Saviour of men; but, upon being asked 'From what did he save mankind?' replied, 'from God.'

"Having heard from the patrons that the scholars were particularly expert in arithmetic, I requested the master to exhibit his best scholars. Thirteen boys accordingly multiplied a given sum of £ s. d. by (25 + ½.) The process was neatly and accurately performed by every boy. I then examined the same class in arithmetic, and set each boy a distinct sum in multiplication of money. Instead of (25 + ½) I gave 5 as the number by which the several sums were to be multiplied. I allowed each boy for this simple process twice as much time as he had required for the preceding, which was far more complicated; but only two of the 13 could bring me a correct answer. This is well worthy of remark. The original sum appears to be one which they are in the habit of performing before strangers; many had copied the whole process from those next them, without understanding a single step.

"The girls were further advanced in arithmetic and in Holy Scripture. But the 2d class asserted that St Matthew was one of the prophets; that Jesus Christ is in the grave to this day; and two stated that Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary were the same person. Although these questions were put in English and in Welsh, few of the children could understand what they heard or read in the English language. The questions were therefore interpreted."

We should here observe that a considerable number of the examinations were conducted not by the inspectors themselves, but by persons hired by them, more or less on account of their knowledge of the Welsh language. To these we attach little or no weight, because they have not the sanction of a Government commission, nor do the persons themselves hold any official or private rank by which their capacities for conducting such examinations can be ascertained.

As a specimen of the state in which some of the peasantry are, we find Mr Lingen, while in Pembrokeshire, remarking thus: —

"I entered two cottages, where the children were said not to be attending school. In the first I found an extremely well-spoken and intelligent girl of twelve or thirteen years old, and her brother somewhat younger. They had been to Yerbeston day-school for about a quarter, and to Molleston Sunday-school for about two years, though not for the last month. It was closed during the bad weather and short days. She read about Jesus in the Testament; but could tell me nothing about him except that he was called the Son of Man. She said, 'They only teach us to read; they don't tell us any of these things at the Sunday-school.'

"In the other cottage I found two little children, a boy and girl, going, and having been, to no school of any kind. The girl was nursing an infant: there were two other children from home. The mother of four of them was a widow, the fifth child was apparently a pauper, billeted upon her in consideration of 5s. per week from the parish. At the time of my visit the mother was out at farm-work (winnowing), and had to be called; I could get no answer from the two children. The girl, who was the eldest, and in her ninth year, only replied to my questions by a cunning, unpleasant grin, though her face was intelligent and not ill-looking. The boy had a most villainous expression of sullen stolidity; he was mixing culm with his hands. They knew no prayers, nor who to pray to – and of course never prayed. The mother could not read nor write – 'worse luck,' as she said; her only chance of educating these children was a free-school. The entire 5s. went in food at the present high prices, and 'not enough then.'

"In this same neighbourhood I asked some questions of a little boy, nearly seven, whom I met on the road. It was in vain that I tempted him with half-pence to answer; he knew nothing of Sunday – of God – of the devil – 'had heard of Jesus Christ from Jemmy Wilson,' but could give no account whatever about him; he knew neither the then day of the week, nor how many days in a week, nor months in a year; he had never been in any school; his brother and sister were going to St Issell's school. I had to repeat my questions two or three times over before they seemed to impress any thing more than his ears. The first answer invariably was, and it was, often repeated half a dozen times – 'What ee' say?' and the next 'Do' know.'"

The condition of the buildings in which the schools are commonly held in the country parishes is wretched in the extreme. Take the following brief accounts, some of which might furnish admirable sketches to a Cattermole or a Maclise: —

"(1.) The school was held in a miserable room over the stable; it was lighted by two small glazed windows, and was very low; in one corner was a broken bench, some sacks, and a worn-out basket; another corner was boarded off for storing tiles and mortar belonging to the chapel. The furniture consisted of one small square table for the master, two larger ones for the children, and a few benches, all in a wretched state of repair. There were several panes of glass broken in the windows; in one place paper served the place of glass, and in another a slate, to keep out wind and rain; the door was also in a very dilapidated condition. On the beams which crossed the room were a ladder and two larch poles.

"(2.) The school was held in a room built in a corner of the churchyard; it was an open-roofed room; the floor was of the bare earth, and very uneven; the room was lighted by two small glazed windows, one-third of each of which was patched up with boards. The furniture consisted of a small square table for the master, one square table for the pupils, and seven or eight benches, some of which were in good repair, and others very bad. The biers belonging to the church were placed on the beams which ran across the room. At one end of the room was a heap of coal and some rubbish, and a worn-out basket, and on one side was a new door leaning against the wall, and intended for the stable belonging to the church. The door of the schoolroom was in a very bad condition, there being large holes in it, through which cold currents of air were continually flowing."

If, however, the condition of the school-buildings is thus unsuitable, the previous education and training of the teachers is not less faulty. The subjoined extract from Mr Lingen's report is borne out by precisely similar statements from those of his coadjutors: —

"The present average age of teachers is upwards of 40 years; that at which they commenced their vocation upwards of 30; the number trained is 12·5 per cent of the whole ascertained number; the average period of training is 7·30 months; the average income is L.22, 10s. 9d. per annum; besides which, 16·1 per cent have a house rent-free. Before adopting their present profession, 6 had been assistants in schools, 3 attorneys' clerks, 1 attorney's clerk and sheriff's officer, 1 apprentice to an ironmonger, 1 assistant to a draper, 1 agent, 1 artilleryman, 1 articled clerk, 2 accountants, 1 auctioneer's clerk, 1 actuary in a savings' bank, 3 bookbinders, 1 butler, 1 barber, 1 blacksmith, 4 bonnet-makers, 2 booksellers, 1 bookkeeper, 15 commercial clerks, 3 colliers, 1 cordwainer, 7 carpenters, 1 compositor, 1 copyist, 3 cabinet-makers, 3 cooks, 1 corn-dealer, 3 druggists, 42 milliners, 20 domestic servants, 10 drapers, 4 excise-men, 61 farmers, 25 farm-servants, 1 farm-bailiff, 1 fisherman, 2 governesses, 7 grocers, 1 glover, 1 gardener, 177 at home or in school, 1 herald-chaser, 4 housekeepers, 2 hatters, 1 helper in a stable, 8 hucksters or shopkeepers, 1 iron-roller, 6 joiners, 1 knitter, 13 labourers, 4 laundresses, 1 lime-burner, 1 lay-vicar, 5 ladies'-maids, 1 lieutenant R. N., 2 land-surveyors, 22 mariners, 1 mill-wright, 108 married women, 7 ministers, 1 mechanic, 1 miner, 2 mineral agents, 5 masons, 1 mate, 1 maltster, 1 militia-man, 1 musician, 1 musical-wire-drawer, 2 nursery-maids, 1 night-schoolmaster, 1 publican's wife (separated from her husband,) 2 preparing for the church, 1 policeman, 1 pedlar, 1 publican, 1 potter, 1 purser's steward, 1 planter, 2 private tutors, 1 quarryman, 1 reed-thatcher, 28 sempstresses, 1 second master R. N., 4 soldiers, 14 shoemakers, 2 machine-weighers, 1 stonecutter, 1 serjeant of marines, 1 sawyer, 1 surgeon, 1 ship's cook, 7 tailors, 1 tailor and marine, 1 tiler, 17 widows, 4 weavers, and 60 unascertained, or having had no previous occupation.

"In connexion with the vocation of teacher, 2 follow that of assistant-overseer of roads, 6 are assistant overseers of the poor, 1 accountant, 1 assistant parish clerk, 1 bookbinder, 1 broom and clog-maker, 4 bonnet-makers, 1 sells Berlin wool, 2 are cow-keepers, 3 collectors of taxes, 1 drover (in summer,) 12 dressmakers, 1 druggist, 1 farmer, 4 grocers, 3 hucksters or shopkeepers, 1 inspector of weights and measures, 1 knitter, 2 land-surveyors (one of them is also a stonecutter,) 2 lodging-house keepers, 1 librarian to a mechanics' institute, 16 ministers, 1 master of a workhouse, 1 matron of a lying-in hospital, 3 mat-makers, 13 preachers, 18 parish or vestry clerks (uniting in some instances the office of sexton), 1 printer and engraver, 1 porter, barber, and layer-out of the dead in a workhouse, 4 publicans, 1 registrar of marriages, 11 sempstresses, 1 shopman (on Saturdays,) 8 secretaries to benefit societies, 1 sexton, 2 shoemakers, 1 tailor, 1 teacher of modern languages, 1 turnpike man, 1 tobacconist, 1 writing-master in a grammar-school, and 9 are in receipt of parochial relief."

Upon this the inspector observes with great good sense —

"No observations of mine could heighten the contrast which facts like the above exhibit, between the actual and the proper position of a teacher. I found this office almost every where one of the least esteemed and worst remunerated; one of those vocations which serve as the sinks of all others, and which might be described as guilds of refuge; for to what other grade can the office of teacher be referred after the foregoing analysis? Is it credible that, if we took 784 shoemakers, tailors, carpenters, or any other skilled workmen, we should find them (one with another) not to have commenced their calling before 30 years of age? nor more than 47·3 per cent of them who had not previously followed some other calling nor more than 1 in every 8 who had served any apprenticeship to it, nor even this 8th man for a period much longer than half a year? The miserable pittance which they get is irregularly paid."

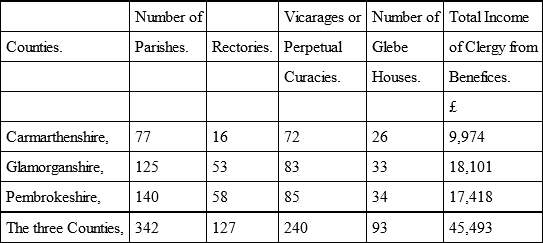

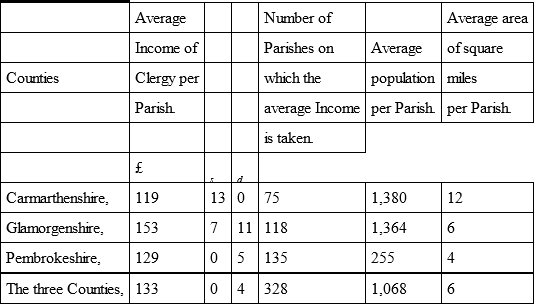

The pecuniary part of the question, the ways and means for supporting an efficient system of education in Wales, may be very fairly inferred from the following extract of the report on three of the most prosperous counties in the principality, corroborated as it is by similar statements and returns in other districts: —

"There is a great and general deficiency of voluntary funds for the maintenance of schools for the poor in the rural parts of South Wales. By far the most liberal contributors to such schools in England are the clergy. The following table exhibits the clerical income of the beneficed clergy in my district. I would beg to call particular attention to the average area and population of the parishes in Carmarthenshire, and to the income of the clergy in the remote hundreds of Dewisland and Kemess: —

"The poor provision which the church offers to an educated man, and the necessity of ordaining those only, for the great majority of parishes, who understand the Welsh language, are facts which bear powerfully upon the education of the country. A large portion of the Welsh clergy complete their education exclusively in Wales. The licensed grammar schools, from which they were formerly ordained, have been superseded for St David's College, Lampeter.

"Still, so far as daily education has hitherto been supported by voluntary payments, this has been mostly in connexion with the church. For, putting aside 31·1 per cent of the day-scholars as belonging to private adventure schools, and 10·9 percent for children in union workhouse and workmen's schools, there remains 39·9 per cent of the day-scholars in connexion, and 18·1 per cent not in connexion, with the church."

Whatever deficiencies there may be in the system of daily and secular education, much more zeal and energy is shown in the Sunday schools; the causes and objects of which are so graphically and accurately described by Mr Lingen, that we must again quote his own words: – observing that the two other reports tell the same tale exactly, only in different language —

"The type of such Sunday schools is no more than this. A congregation meets in its chapel. It elects those whom it considers to be its most worthy members, intellectually and religiously, to act as 'teachers' to the rest, and one or more to 'superintend' the whole. Bible classes, Testament classes, and classes of such as cannot yet read, are formed. They meet once, generally from 2 to 4 P.M., sometimes in the morning also, on each Sunday. The superintendent, or one of the teachers, begins the school by prayer; they then sing; then follows the class instruction, the Bible and Testament classes reading and discussing the Scriptures, the others learning to read; school is closed in the same way as it began. Sections of the same congregation, where distance or other causes render it difficult for them to assemble in the chapel, establish similar schools elsewhere. These are called branches. The constitution throughout is purely democratic, presenting an office and some sort of title to almost every man who is able and willing to take an active part in its administration, without much reference to his social position during the other six days of the week. My returns show 11,000 voluntary teachers, with an allowance of about seven scholars to each. Whatever may be the accuracy of the numbers, I believe this relative proportion to be not far wrong. The position of teacher is coveted as a distinction, and is multiplied accordingly. It is not unfrequently the first prize to which the most proficient pupils in the parochial schools look. For them it is a step towards the office of preacher and minister. The universality of these schools, and the large proportion of the persons attending them who take part in their government, have very generally familiarised the people with some of the more ordinary terms and methods of organisation, such as committee, secretary, and so forth.

"Thus, there is every thing about such institutions which can recommend them to the popular taste. They gratify that gregarious sociability which animates the Welsh towards each other. They present the charms of office to those who, on all other occasions, are subject; and of distinction to those who have no other chance of distinguishing themselves. The topics current in them are those of the most general interest; and are treated in a mode partly didactic, partly polemical, partly rhetorical, the most universally appreciated. Finally, every man, woman, and child feels comfortably at home in them. It is all among neighbours and equals. Whatever ignorance is shown there, whatever mistakes are made, whatever strange speculations are started, there are no superiors to smile and open their eyes. Common habits of thought pervade all. They are intelligible or excusable to one another. Hence, every one that has got any thing to say is under no restraint from saying it. Whatever such Sunday-schools may be as places of instruction, they are real fields of mental activity. The Welsh working man rouses himself for them. Sunday is to him more than a day of bodily rest and devotion. It is his best chance, all the week through, of showing himself in his own character. He marks his sense of it by a suit of clothes regarded with a feeling hardly less Sabbatical than the day itself. I do not remember to have seen an adult in rags in a single Sunday school throughout the poorest districts. They always seemed to me better dressed on Sundays than the same classes in England."

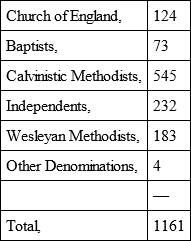

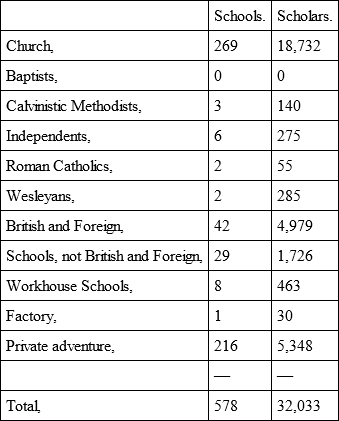

As a specimen of the relative number of Sunday schools belonging to the different religious persuasions in North Wales, we will take Mr Johnson's summary, which gives the following tabular result; and which is nearly in the same proportion in the rest of the principality: —

SUNDAY SCHOOLS.

But if we take the returns of the daily schools for the same six counties, the proportions will be found to, be greatly changed: —

DAY SCHOOLS FOR THE POOR.

Out of these daily schools for the poor, not less than 269, or 46½ per cent of the whole number, (to say nothing of many of the private schools,) are publicly provided by the Church; and it should be remembered that of the Dissenting Sunday schools nearly all are held in their meeting-houses, and form part and parcel of their religious system; whereas the Church Sunday school is mostly an institution apart from the church itself, and established on its own separate footing.

With regard to the funds for supporting schools, the following remarks by Mr Johnson, as applied to North Wales, are too important to be omitted. He says: —

"It appears, from the foregoing analysis of the funds of 517 schools, that the amount annually raised by charitable contributions of the rich is (in round numbers) £5675, that raised by the poor £7000. It is important to observe the misdirection of these branches of school income, and the fatal consequences which ensue.

"The wealthy classes who contribute towards education belong to the Established Church; the poor who are to be educated are Dissenters. The former will not aid in supporting neutral schools; the latter withhold their children from such as require conformity to the Established Church. The effects are seen in the co-existence of two classes of schools, both of which are rendered futile – the Church schools supported by the rich, which are thinly attended, and that by the extreme poor; and private-adventure schools, supported by the mass of the poorer classes at an exorbitant expense, and so utterly useless that nothing can account for their existence except the unhealthy division of society, which prevents the rich and poor from co-operating. The Church schools, too feebly supported by the rich to give useful education, are deprived of the support of the poor, which would have sufficed to render them efficient. Thus situated, the promoters are driven to establish premiums, clothing-clubs, and other collateral inducements, in order to overcome the scruples and reluctance of Dissenting parents. The masters, to increase their slender pittance, are induced to connive at the infringement of the rules which require conformity in religion, and allow the parents (sometimes covertly, sometimes with the consent of the promoters) to purchase exemption for a small gratuity; those who cannot afford it being compelled to conform, or expelled in case of refusal. Where, however, the rules are impartially enforced, or the parents too poor to purchase exemption, a compromise follows. The children are allowed to learn the Church catechism, and to attend church, so long as they remain at school, but are cautioned by their parents not to believe the catechism, and to return to their paternal chapels so soon as they have finished schooling. A dispensation, in fact, is given, allowing conformity in matters of religion during the period required for education, provided they allow no impression to be made upon their minds by the ritual and observances to which they conform. The desired object is attained by both parties. Outward conformity is effected for the time, and the children return in after-life to the creed and usages of their parents."