полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 63, No. 391, May, 1848

We are aware of the many difficulties that are sure to meet any government, or rather any political party, that should attempt at the present day to carry into effect a scheme of general education. The sectarian spirit of the country is so thoroughly excited, the minds of the people are so thoroughly wild upon certain subjects, that any thing like a patriotic sinking of interests for the general good is out of the question; much less is it to be expected that, under Whig leaders, the discordant members of the state would be inclined to defer to the superior authority of the legislators. The predominance of the democratic element in the present phase of the constitution of England hinders the action of government, and injures in this, as in most other respects, the very best interests of the country. Still we cannot but think that, were there at the head of affairs a band of statesmen in whose political integrity, private honour, and public capacity, the country could firmly rely, the mass of the people might be made to rally round their standard, rather than round the gathering-posts of factious leaders, whether political or religious. But at the present moment, when the tone of political morality and parliamentary consistency is so low, when treason and tergiversation are the order of the day, and when the undisguised pursuit of gain – by fair means or by foul, but still by some means or other – is allowed to usurp an undue place in the councils of the nation, it is in vain to hope for any very satisfactory results.

We would say, follow out the Church scheme fearlessly and boldly, but without intolerance – follow it out consistently and honestly, and you will obtain more numerous and more worthy followers, you will produce more permanent and more beneficial results, than by truckling to this sect or to that, or by the vain endeavour to curry favour with all. At the same time we think, with the commissioners, that to make the Bible the sole book of education, as is the case in most schools, is a bad plan; it brings the sacred volume itself into contempt and dislike, and it limits the field of instruction in an undue degree. We would introduce more of secular subjects even into the common schools, and certainly not less of real religion; and to that end we would endeavour to fit the teachers for their duties, and suit the extensiveness of the schools to the amount of work to be done. Religious education being maintained daily as a part, not as the whole, of education, it should be made the exclusive topic of Sunday education; and the amount of information on religious topics thus gained would be found to be greater, in a given time, than when the child's mind is bent to that one subject alone – the hardest, the sublimest of all subjects – and when all his thoughts, all his ideas, are concentrated on the Bible, the Prayer-Book, and the Catechism. In this matter, however, the heads of the Church are the authorities with whom the move for improvement ought to originate; and, would they but act with energy and unanimity, there is no doubt that they would carry the weight and influence of the nation along with them.

The third observation we have to offer refers to the lamentably inadequate provision made, in a pecuniary point of view, for the education of the people. Not only are the teachers totally unprepared by previous education, but, even let their talents and acquirements be what they may, their brightest prospect is that of earning less than at any trade to which they may be take themselves – without any prospect of ever, by some turn of fortune's wheel, amassing for themselves a store for their declining years. Work, to be done well, no matter what its nature may be, must be properly recompensed; no system that is not adequately supported with funds can be expected to continue in a state of efficiency – it will speedily degenerate, decline, and ultimately perish.

Not to dwell upon truisms of this kind, we shall at once state what we think would form a sufficient fund for the maintenance of a uniform and effective system of public instruction in Wales, and the means of carrying it into effect. We conceive that the advantages of education, being felt by every man – even whether he be the direct recipient of it or not – should be paid for out of a common fund, raised in an equitable manner by the state. On the other hand, in an agricultural country, where the main interests of the state are in the hands of the great landed proprietors, and where the well-being and safety of the whole depends upon the morality and the physical good of the labouring classes, the magistrates of the country, and all the owners of land, are most intimately bound up with the healthy action and welfare of the whole people; nor can they by any means shift from their shoulders the duty of providing for the happiness of their tenants and dependents. For similar reasons, the merchants, manufacturers, and other citizens of large towns, have a direct interest in the welfare and in the in moral advancement of all the working and inferior classes of the urban population. Now, we maintain that one of the most efficient and ready methods for the promotion of industry, the suppression of vagrancy, the diminution of drunkenness, sensuality, and crime, and therefore the lowering of poor-rates, police-rates, county-rates, &c., would be the giving the people a better religious and secular education, and the raising of them in the scale of social beings. It would follow from these premises, if assented to, that an education tax would be one of the fairest and most directly advantageous which could be imposed on the country; and we are further persuaded that, as its effects began to make themselves felt, its justice would be acquiesced in by all who should pay it.

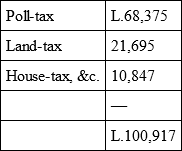

We would therefore suggest, 1st, That a general poll-tax should be raised on the country, without distinction of person, or age, or sex, for the purposes of education; and, in order that people might not murmur at it for its oppressiveness, we would fix it at the value of one day's work of an adult agricultural labourer. 2d, On all the acreage of the country we would recommend a land-tax to be levied, with the same intent, and without exception for any class of property whatsoever. This we would fix at some small fractional part of the annual value of the land in rent charge, – say at one penny per acre. 3d, On all household property in towns, for tenements, belonging to persons not in the condition of labourers, we would lay a similar tax of a small fractional portion of the annual rent; and on all mining and manufacturing property, wherever situated, we would impose a certain small annual charge. To fix ideas, we will suppose that the sum produced by this latter class of property should be equal to one-half of that charged for the same purpose on the landed proprietors. The sums to be raised may be thus calculated: —

1st., The entire population of North and South Wales, as ascertained by the census of 1841, is 911,603: and the average rate of wages for an able-bodied agricultural labourer may be safely estimated at 1s. 6d. per diem, as a minimum throughout Wales, A poll-tax, therefore, of 1s. 6d. per head on the whole population, would produce a sum of £68,375.

2d., The entire acreage of Wales is very nearly 5,206,900 acres; and a land-tax of 1d. per acre would therefore produce £21,695.

3d., Estimating a tax on houses, and mining and manufacturing property throughout Wales, at only half the amount of that raised on the land, we should have a sum of £10,847.

The whole would stand thus: —

Now assuming that, whether by adhering to the old division of parishes for the formation of educational districts – and for many reasons, religious as well as political, we should be sorry to see this arrangement disturbed – there would be required, at the rate of at least one school for each parish, the total number of 863 schools. But on account of the increased size of some of the towns, and the accumulation of mining population in several mountainous districts, it might be necessary to provide more than this number. We will therefore, at a guess, fix it at 1000, and this would furnish at least one school for every 1000 of the whole population, adult as well as infantine – a proportion which will be allowed to be abundantly sufficient, when it is considered that such schools are intended only for the lower classes.

To support, however, a school in a proper state of efficiency – that is to say, to furnish it with properly trained teachers, male and female, and with the requisite books and other instruments of teaching – we do not think that we are overstraining the point if we assign the annual sum of one hundred pounds as necessary. This sum might either be divided in the proportion of sixty pounds per annum for a male teacher, and forty pounds per annum for a female, – or it might most advantageously, in some cases, be bestowed on a teacher and his wife, supposing them both capable of undertaking such duties. Of course, in all cases suitable buildings, including school-rooms for both sexes, residences and gardens for the teachers, should be provided at the public expense, and maintained in repair from a distinct fund. We shall then perceive that the sum mentioned above, amounting in round numbers to one hundred thousand pounds per annum, would be sufficient for the purpose; and we think that it would not only be so, but that, it would be made to furnish a sufficient sum for retiring and superannuated pensions, on the principle adopted in several of the Continental states, of an annual percentage being deducted from the salaries of all civil servants to form a fund of this nature, specially devoted to their own benefit. We do not throw out any specific hints for the collection and management of this fund; but it might be raised along with other local rates, and by the same local officers, so that the smallest possible addition might be thereby made to the cost of collecting it.

One part of this plan, however, without which the whole would be inefficient, would be the forming of a body of inspectors, and the establishing of training-schools or colleges for teachers. The latter are already beginning to exist, and machinery for the former is now at work under the direction of the Committee of Council. But we should hope to see training-schools established on a much larger and more efficient scale than at present; and we should desire to see the appointment of inspectors, and the management of the education funds, taken out of the hands of such a body as the Privy Council, and given to the local and provincial authorities, civil and ecclesiastical, of Wales. If such appointments remained in the hands of government, political jobbing would act upon them with greater intensity than through the medium of local interests and county influence; and, what would be far worse than this, another impulse would be given to the principle of centralisation, one of the most fatal for national spirit and national freedom that can be devised, and which we are called upon to resist at all times, but especially when a party of Whig politico-economists, as wild and destructive in the ultimate tendencies of their theories as the Girondists of France, are in possession of the reins of power.

We say nothing on the subject of Sunday schools; we leave them altogether to the consideration and support of the Church, and the various sects in Wales, by whom, if they are wanted, they can be efficiently maintained without any interference of the state. But we call loudly upon the legislature of the United Kingdom to give at least the initiative and the moving power to the natural inertness of the Welsh people; and we would summon them, as they value the happiness, the tranquillity, and the moral advancement of that portion of the country, to take the matter of education under their primary control, and to form a general system, harmonious in its manner of working, comprehensive in its extent, and tolerant in its religious tendencies. Much opposition and prejudice and clamour would have to be combated, as upon every question seems now to be the case in what we fondly consider the model of all political constitutions. But unless the legislature and the statesmen at the head of affairs are prepared to meet these obstacles, and to remove them in their sovereign wisdom, they had better declare their incapacity openly, and renounce their functions.

THE SILVER CROSS. – A CAMPAIGNING SKETCH

FROM THE GERMAN OF ERNEST KOCHNIGHT-QUARTERS4In the village of Careta, upon the mountains near the Arga, which flows from the Pyrenees to Pampeluna, the wind whistled and the snow drifted upon a stormy January evening of the year 1836. It was about seven of the clock: José, a sturdy peasant, sat by his kitchen fire, on which withered vine-branches blazed and crackled, and dried his hempen sandals. Beside him knelt a haggard old woman, handsome in the ugliness of one of those strongly-marked, melancholy, yellow countenances, in which a legend of the Alhambra seems to lurk. Dressed in rusty black, she crouched like an animal by the hearth, poking and blowing at the fire, which sometimes broadly illuminated the remotest corners of the room and rafters of the roof, at others was barely sufficiently vivid to light up her mysterious old physiognomy. Suddenly a tremendous gust of wind burst open the wooden shutter, and howled into the apartment.

"Dios! what weather!" croaked the old woman.

An affirmative carajo was her husband's reply, as he knocked the dry mud from his leathern gamashes against the edge of the raised hearthstone.

"God help the poor troops in the mountains!" continued the old woman. "Daughter, shut the window."

A young girl, who sat, spindle in hand, upon a wooden bench in the gloom of the chimney corner, obeyed the order. Her coarse woollen dress could not wholly disguise the graces of her form, as she tripped across the kitchen through the fitful firelight, which shone upon her gipsy features and clear brown skin, and upon the two long plaited tails of jet-black hair that fell down her back nearly to her heels. Before closing the window she listened, with the true instinct of a vedette, to the sounds without. In a lull of the blast, her ear caught the noise of distant drums, beaten not in irregular guerilla fashion, but by well-trained drummers, in steady quick time.

"Father," cried Manuela, "troops are at hand."

"Nonsense, child: 'tis the garrison tattoo below at Larasuena."

"No, father, it draws nearer. 'Tis the French. Mother, hide the beds."

Beds were hidden, a sack of white beans was carefully concealed, the family jackass was tethered in the darkest corner of the cellar-like stable. Preceded by rattle of drums, two wet and weary battalions of the French Legion marched into Careta, and after a few minutes' halt the shivering alcalde was hurrying from house to house, allotting quarters to the tired strangers.

An hour later I sat beside José's hearth, smoking a friendly cigarillo, with the surly old peasant. Upon the earthen floor, at various distances from the fire, at which sundry pair of white gaiters, newly washed, hung to dry, lay those soldiers of my squad (I was then a corporal) who had not fallen in that day's fight by Larasuena. At a sort of loop-hole in the wall, looking out into the street, a sentry stood. For a long while José sat with folded hands, gazing at the fire. I did all I could to make him talk; told him about German customs and German men; then spoke of Spain, of the Constitution and so forth; less, however, if truth must be told, with a view to his amusement than to that of the sweet-faced girl with the long black locks who sat over her spindle in the opposite corner. At last José's sullenness thawed so far that he asked me very earnestly if the German jackasses were as big and as strong as those in Navarre. What could I reply to such a question!

Suddenly a long shrill whistle was heard outside the house. "Keep a bright look-out!" cried I, to the sentry at the loophole. Again all was still. Father José dropped off to sleep; the patrona went down stairs to fodder the donkey, and I addressed my conversation to pretty Manuela. I know not how it was, but we got on so well together that soon I found myself seated close beside her, one arm round her waist, whilst the other hand played with a silver cross that hung from her neck, and on which were engraved the words, "Mary, pray for me!" And she told me of her brother Antonio, who was away from home, and of her sister Maria, who was with relations at Hostiz, in the valley of the Bastan.

"And where is your brother Antonio, Manuela?"

"My brother is – in the mountains. You seem good and kind, stranger; you tell me you are not a Frenchman, but a German. Oh! if you meet my brother in fight, do not kill him – spare him for my sake!"

"But, dear Manuela, how am I to know your brother? One Carlist is so like another."

"No, no! you are sure to know him: he resembles me, and he wears upon his breast a silver cross like mine. The same words are written upon it, and not a bullet has touched him since he has worn it."

"So, your brother is a soldier of Don Carlos, your sister dwells in a Carlist village, and your parents – at least your father, judging from his looks when I spoke of the Constitution, – also hold for the Pretender. Do you not fear Christino troops?"

"No, Señor – at least I should not, if they were all as good as you, who protected me from that rude Italian. —Dios!" she exclaimed, suddenly interrupting herself, and springing from her chair like a scared deer. From under the bench on the other side of the fire peered forth the dark countenance of a Piedmontese soldier, his checks flushed with wine, his eyes sparkling with a sullen fire, his ignoble, satyr-like features expressing a host of evil passions. He shot a venomous glance from under his dirty eyelashes, then turned himself round, grinding between his teeth an Italian malediction. He still lay where I had violently thrown him, when, upon our first entrance, I rescued Manuela from his brutality.

"To bed, girl!" screamed the old woman, who just then re-entered the kitchen. Manuela went to bed, and I composed myself to sleep upon the bench by the fire. It was eleven o'clock, and the silence in the village was unbroken save by the howling of the storm and the occasional challenge of a sentry.

IN THE MOUNTAINSThe road from Pampeluna to France passes by a mountain of some size, whose real name I have forgotten, but which our soldiers called the Hill of Death, because, for a league around, it emitted an odour of unburied corpses. Close to the road, but at a considerable elevation, a conical peak springs from the hill-side.

Around this peak, upon a July night, about six months after the scene at Careta, lay a column of Carlists, awaiting the dawn. There they are, scattered about the fires, forlorn figures of unconquerable endurance, barefoot, in linen trousers and thin cloth jackets, the scarlet plate-shaped cap upon their heads. Burnt brown by the Castilian sun, their daring picturesque countenances assume an additional wildness of aspect in the red light of the watch-fires. From one of these, Fernando, a handsome Arragonese lad, whose father and brothers have been shot, and whose sister is a fille-de-joie at Saragossa, snatches a charcoal with his fingers, and places it upon a stone, to light his paper cigar. Then comes Hippolito, a pale emaciated boy of sixteen, and sets upon the fire a small pot of potatoes, which he has carried with him since morning. The Carlists caught him in Catalonia, and dragged him along with them, and often does he swear a peevish oath that his death will be in the hospital. Beside him lies Cyrillo, a desperate scapegrace from Estremadura, intended for the university, but whom restlessness and evil courses have brought under the banners. He has a piece of bacon on his bayonet, and toasts it at the flame. Hard by, a brace of Andalusians have got a guitar, and strike up a melody, so plaintive and yet so strangely spirit-stirring, that a bearded dragoon, slumbering upon his back, with his hands beneath his head, suddenly opens his great wild eyes. One of his comrades stands near him, his arms folded on his breast, gazing down wistfully into the valley of the Arga, now veiled by the mists of evening, and which he perhaps for many a long day has not dared to visit – as if the tones of the guitar brought melancholy to his mind. Suddenly the measure is changed, and the musician breaks into the lively fandango; a joyous Navarrese seizes the pensive trooper by the arm and whirls him round, but receives in return a push that sends him staggering against the guitar player, whilst he grasps at his girdle for the ready knife. An obscene curse burst from half-a-dozen throats; with fierce looks the two men confront each other, but are separated by force, and again the guitar tinkles in the night air, whilst Hippolito gathers up his potatoes, upset and scattered in the scuffle. A dirty priest comes up, a decoration upon his black coat, and enjoins order and peace. He has scarcely walked away, when a soldier in handsome uniform rushes up to the fire, and throws himself down, breathless and half fainting. He is a deserter from the Christino regiment of Cordova. They give him unlimited wine, and he tells them the latest news from the hostile camp. The bota passes from mouth to mouth; and whilst the deserter sleeps off his libations and fatigue, his new comrades cast lots for his good shirt and strong shoes.

The same evening four battalions of the foreign legion were quartered at Villalba, four leagues nearer to Pampeluna. Upon an open space in the village, whence the sun had long since burned away the grass, a party of Germans sat upon scattered blocks of stone, and discussed, whilst a gourd of wine circulated slowly amongst them, an order just issued to hold themselves ready to march at a minute's notice.

"Who knows," said one of them, a tailor from Regensburg, "whether we shall be alive to-morrow? Let's have a song."

"A song, a song!" repeated another, a shoemaker from Rhenish Prussia, who had found himself uncomfortable in the Vauban barracks in Luxemburg.

"What shall it be?" cried a journeyman mechanic, who, when upon his travels, ran short of work and money.

Before any one could answer, a capering Frenchman struck up,

"Entendez-vous, le tambour bat, le clairon sonne," &c"Hold your infernal French tongue!" shouted the Germans. "Here's the sergeant from Munich will give us a song."

The Bavarian, nothing loath, struck up a song, whose simple strain and familiar words brought home and friends to the memory of all present. The melody echoed far through the still evening air, and, when it concluded, tears were in every eye, and no one spoke, save the Regensburg tailor, who muttered,

"God take us safe out of this cutthroat country!"

The sun went down. A few pieces of ship-biscuit were shared for the evening meal, and then the drums beat to roll-call, which was held in quarters, and at whose next repetition many a man then present was doomed to be missing.

That same night, twelve o'clock had scarcely struck, when the three solemn taps with which the French générale begins, resounded through the village of Villalba. In less than ten minutes the battalions were under arms, hurrying at quick step along the desolate road to Larasuena. In a meadow, outside this village, half an hour's halt was allowed, for the men to fill their flasks with vinegar and water, as a remedy for the faintness occasioned by heat. Then the march continued. The column had scarcely halted, for the second time, in rear of the houses of Zubiri, when a sharp fire of musketry was heard from the mountain above. At charging pace the weary troops hurried up the steep acclivity. The sun was scorching hot; the knapsacks seemed insupportably heavy. Nearer and nearer was the noise of the fight; in the ranks of the ascending soldiers short suppressed gasps and groans were heard. The tailor from Regensburg fell forward, with froth upon his lips, and gave up the ghost.

On reaching a small level, we saw it was high time for our arrival. The second regiment of the royal guard already gave ground, when the cry "La Legion!" changed the fortune of the day. With fixed bayonets our battalions rushed like tigers upon the factious ranks, which were disordered by the shock. The Bavarian sergeant fell amongst five Carlists, who settled him with their knives. A pale subaltern of the factious came in contact with three of our grenadiers, and begged piteously for mercy. But the grenadiers had no time; they cut a bad joke in Swabian dialect, and brained him with their muskets. Of the first encounter of the day, these are the only episodes I remember. Suddenly the Carlist bugles sounded the retreat. We formed column and hurried in pursuit, followed by the royal guard. From time to time the enemy halted, till the bayonet again dislodged them. By turns our battalions were sent forward as skirmishers. It was nearly noon. A dying officer of ours begged me for a mouthful of vinegar. I had but two; one for myself, and one for my comrade, whom I had not seen, however, the whole of the day, and never saw afterwards. It was about twelve o'clock when my company advanced to skirmish. The line deployed, and as we slowly advanced, loading and firing, I had to pass through the corner of a small thicket. Just as I entered it, I observed a Carlist horseman, at its other extremity, fire his carbine at one of our men. Then he disappeared amongst the trees, and five seconds later I saw him riding towards me. "Surrender!" he shouted in Navarrese patois, and stooped behind his horse's head. At my shot the animal stood stock-still, and the rider fell from his saddle. Blood streamed from a wound between neck and shoulder. I released his foot from the stirrup, propped him up against a beech-tree, and unbuttoned his jacket from over his panting breast. As I did so, a silver cross fell almost into my hand. It hung from his neck by a ribbon, and upon it were the words, "Mary, pray for me!" I had seen such a cross before. "Open your mouth, Antonio!" I cried. He obeyed, and I poured upon his parched tongue the last contents of my flask. He thanked me with his dying breath. I concealed the cross within his jacket, and followed the signal that called the skirmishers forward.