полная версия

полная версияAustralasian Democracy

But how, it may be asked, has an equitable assessment of the land been secured for the purposes of the tax? Any owner who is not satisfied with the value placed upon his land on the assessment roll, may require the Commissioner to reduce the assessment to the amount specified on the owner's return, or to purchase the land at the sum mentioned on the owner's return of its actual value inclusive of improvements. The Commissioner is bound to make the reduction unless the Government approve of the acquisition of the land. A reasonable balance is thus struck: the Government are unwilling to have a large amount of land thrown on their hands, while the owner does not take the risk of the resumption of the land at an inadequate valuation. Disputes between the Commissioner and owners have, in most cases, been adjusted satisfactorily; but the Government decided to buy the Cheviot Estate of 85,000 acres, which lies close to the sea in the Middle Island. Upon its purchase they at first let the pastoral lands temporarily at the rate of £8,862 a year, while their surveyors laid out the country and supervised the construction of roads. The results of the transaction were, in 1896, eminently satisfactory; the capital value of the estate then stood at £271,700, and the annual rental at £14,300; and the few inhabitants engaged in pastoral pursuits had been replaced by 216 settlers and their families, who were reported to be of a good class and to have done a large amount of work in the improvement of their lands.

The principal Act dealing with the alienation of Crown Lands is that of 1892, which consolidates and amends former legislation. Crown Lands are divided into urban, suburban, and village lands, which are sold by auction at an upset price, and rural lands, which are again subdivided according to their adaptability for cultivation or pasturage. When townships are being laid out on Crown Lands, one-tenth of the superficial area is to be reserved for purposes of recreation, and a similar extent as a nucleus of municipal property, to be vested subsequently as an endowment in the local authority in addition to the reserves necessary for all public purposes. At the option of the applicant, lands may be purchased for cash, or be selected for occupation with the right of purchase, or on lease in perpetuity. Selectors are limited to 640 acres of first-class land, or 2,000 acres of second-class land, the maximum being inclusive of any lands which they may already hold. The object of this provision is to prevent existing landowners from aggregating large estates by the purchase of Crown Lands. Cash sales are effected at a price of not less than 20s. and 5s. per acre, respectively, for first-class and second-class land, and entitle the selector to a free-hold title upon the expenditure of a prescribed amount on improvements. Land selected under occupation with the right of purchase is subject to a rental of 5 per cent. upon the cash price, under lease in perpetuity, which is for 999 years, to a rental of 4 per cent.; and strict conditions of residence and improvement are, in both cases, attached and rigidly enforced. At the expiration of ten years, a licensee under the former tenure may, upon payment of the upset price, acquire the freehold or may change the license for a lease in perpetuity. The latter is the perpetual lease of the previous Acts, denuded of the option of purchase and of the periodical revaluation of the rent, and is, in the latter respect, reactionary, as the State gives up its right to take advantage of any unearned increment. Subsidies amounting to one-third of the rent of land taken up under any of the above tenures and one-fourth of the rent of small grazing-runs are paid to local authorities for the construction of roads, but must be expended for the benefit of the selectors from whose lands such moneys are derived. The Act of 1892 also authorises the Governor to reserve blocks of country, as special settlements or village settlements, for persons who may desire to take up adjacent lands. The Village Settlements have been successful when they have been formed in localities in which there was a demand for labour; the Special Settlements comparative failures, because many of the members of the associations had neither the requisite means nor knowledge of rural pursuits. Pastoral land is let by auction in areas capable of carrying not more than 20,000 sheep or 4,000 head of cattle; or in small grazing-runs not exceeding, according to the quality of the soil, 5,000 or 20,000 acres in area. The dominant feature in the Act, in its application to pastoral as well as agricultural land, is the strict limitation of the area which may be held by any one person; rightly or wrongly, the Government are determined that the Crown Lands shall not pass into the hands of large holders. The principal transactions of the last three years are thus summarised, the figures for 1894 covering the period from April, 1893, to March, 1894, and so for the other years:

In regard to the numerical superiority of leases in perpetuity, it must be pointed out that, not only the special blocks, but the improved farms and lands offered under the Land for Settlements Acts, to which I shall have occasion to refer, are disposed of solely under that tenure; but it appears to be attractive in itself: as most of the Crown Lands require considerable outlay before they become productive, a selector can expend any capital that he may possess more advantageously upon the development of the capabilities of the soil than upon the acquisition of the freehold. The Government also are benefited by a policy which renders the land revenue a permanent asset in the finances. The receipts for the financial year 1895-6 amounted to nearly £300,000.

In 1892 an attempt was also made to deal with the problem of the scarcity of available land in settled districts which was caused by the prevalence of large estates. It was thought that the labourers employed upon them, and the sons of farmers who might wish to settle near their parents, should have an opportunity of acquiring land. The Government, accordingly, passed the first of a series of Land for Settlements Acts, which authorised the repurchase or exchange of lands and their subdivision for purposes of close settlement. Upon the recommendation of a Board of Land Purchase Commissioners, some of whom represent local interests, that a certain estate is suitable for settlement, and should be purchased at a certain price, the Government may enter into negotiations with the owner with a view to a voluntary transaction, and, upon his refusal, take the land compulsorily at a valuation fixed by a Compensation Court. Owners are so far safeguarded that they cannot be dispossessed of estates of less than 640 acres of first-class, or 2,000 acres of second-class land, that they can claim to retain the above area, and that they can require the Government to take the whole of their estates. The maximum annual expenditure was limited at first to £50,000, but has been raised to £250,000. At the end of March of last year twenty-eight estates, containing 87,000 acres, had been acquired, in one case compulsorily, and made available for settlement by surveys and the construction of roads at a total expenditure of nearly £390,000. Nineteen of these had already been subdivided into farms of various sizes, and were bringing in rentals amounting to 4.76 per cent. upon the outlay which they had involved. The Land Purchase Inspector was able to report that the lands, which had been the object of eager competition, had, in most cases, been greatly improved and were in good condition, and he is likely to find even better results in the future, as the Amending Act of 1896 provided that applications for land should not be entertained unless the applicants were able to prove their ability properly to cultivate the soil and to fulfil the stipulations of the leases. This provision is of great importance, as much of the land has been cultivated by its former owners, and would deteriorate rapidly under incapable management. The Governments of South Australia, Queensland, and Western Australia have legislated in a similar direction, and that of New South Wales introduced a Bill which failed to become law. As far as New Zealand is concerned, which has conducted its operations on the largest scale, the system has not been sufficiently long in existence to enable an estimate to be formed of its probable financial results.

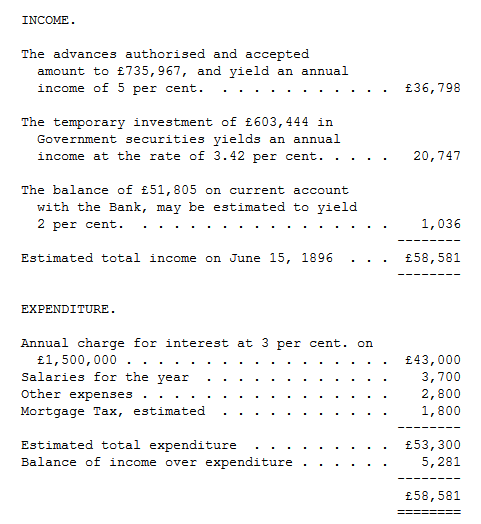

A similar uncertainty prevails in regard to the more recent attempts to place cheap money within the reach of settlers. The first step in that direction was taken in 1886, when regulations were made for the establishment of Village Settlements, the members of which might receive loans for the construction of their houses and for other purposes. These settlements were not, as in some of the Australian Provinces, formed on a co-operative or a semi-communistic basis. The success of this experiment doubtless encouraged the Government to widen the scope of the advances. In 1895, 4,560 persons, divided among 144 settlements, had occupied 33,800 acres of land; they had received £25,800 in advances, had paid £17,600 in rent and interest, and had carried out improvements of the value of £92,800. These improvements, consequently, form an ample security for the repayment of the loans. The necessity of a general scheme of advances was based upon the difficulty experienced by small settlers, however good might be the security, in obtaining loans except at prohibitive rates. Authority was, accordingly, obtained through the Government Advances to Settlers Acts of 1894-6 to borrow three millions with a view to loans ranging from £25 to £3,000, upon first mortgages, to owners of freehold land and occupiers of Crown Lands, the advances not to exceed three-fifths of the value of the former and one-half of the value of the lessee's interest in the latter. Advances may not be made on town lands, nor on suburban lands which are held for residential or manufacturing purposes. The valuation of every security is to be carried out by or on behalf of a superintendent appointed ad hoc., and is to be submitted for the consideration of a General Board consisting of the Colonial Treasurer, the Superintendent, the Public Trustee, the Commissioner of Taxes, and a nominee of the Governor in Council. The advances on freehold land may be either for a fixed period at 5 per cent., or for 36-½ years at 6 per cent., of which 5 per cent. is reckoned as interest and 1 per cent. towards the gradual repayment of the principal; on leasehold lands, in the latter form alone. As the loan of a million and a half raised as the source of advances was floated at 3 per cent., and realised nearly £1,400,000, the margin between the percentage due by the Government and that received from the settlers should be sufficient to enable one-tenth of the interest to be paid, as provided, into an Assurance Fund against possible losses, and a residue to be available which will cover the general expenses of administration. But it is obvious that the result of the experiment will depend greatly upon the prevalent rate of interest and the price of produce. Hitherto, two-thirds of the advances have been used by settlers to enable them to rid themselves of former and less advantageous mortgages; in some cases, mortgagees, in order to retain their mortgages, have voluntarily lowered the rate of interest to 5 per cent. The tabular statement on the following page of the financial position is the latest that has been issued, and does not purport to be more than approximately correct. Advances may also be made towards the construction of dwelling-houses to those who have obtained selections under the Land for Settlements Acts; but they may not exceed twenty pounds nor the amount already spent by the applicant upon his holding.

Another measure which may affect the well-being of settlers is the Family Home Protection Act, 1895. Any owner of land may settle as a family home the land, not exceeding, with all improvements, £1,500 in value, on which he resides and has his home, provided that at the time the land is unencumbered and he is able to pay all his debts without the land in question. As a precaution against the concealment of liabilities, he is obliged to make an application to a District Land Registrar, who must thereupon give public notice of the intended registration. Should any creditor put in a claim within twelve months, the case is to be tried before a Judge of the Supreme Court, and if the owner of the land is vindicated, the Registrar is to issue a certificate which will exempt the family home from seizure under ordinary processes of law, but not in one or two contingencies, of which the principal is the failure to meet current liabilities in respect of rates or taxes. The registration is to continue until the death of the owner or the majority or death under the age of twenty-one of all his children, and is not to precede the last of these events. Upon its cessation it may be renewed at the option of the persons then holding the estate, who must be relations of the deceased. Little effect has been given to the Act owing, probably, to the unavoidable publicity of the proceedings. It appears to have been based upon a South Australian Act of 1891, which enables holders of workmen's blocks, by the endorsement of their leases, to secure for their properties somewhat similar exemptions from seizure. Their failure to avail themselves, to any considerable extent, of this privilege is attributed to the unwillingness of working men to take any trouble in a matter of which the advantages are merely contingent.

So far I have discussed the legislation of New Zealand which affects freeholders and those who are, or desire to become, tenants of the Crown; but before proceeding to deal with matters of common import to most settlers, I must point out that tenants holding from private landlords have also engaged the paternal attention of the Government. The Minister of Lands introduced last session, but failed to pass, a Fair Rent Bill, which would have established a system of Land Courts under the presidency of Stipendiary Magistrates. Landlords and tenants would have had an equal right to apply for the determination of the fair rent which, upon the decision of the Court, whether it were higher or lower than the reserved rent, would have been deemed, until a further revision, to be the rent payable under the lease. The Government displayed great inconsistency in the introduction of the measure; having shown, in the system of lease in perpetuity, that they objected to the periodical revaluation of the rents payable upon Crown Lands, they proposed, through the Fair Rent Bill, to enable the Crown, as landlord, to take steps to increase the rents of its tenants.

As regards the general interests of producers, the Government have, through reductions amounting to £50,000 a year in railway rates, made a concession to them at the expense of the general taxpayer, as the railways, after payment of working expenses, return only 2.8 per cent., a sum insufficient to meet the interest upon their cost of construction. Again, they have appointed experts in butter-making, fruit-growing, &c., who travel about the country and give technical instruction by means of lectures; and they distribute, among farmers and others, pamphlets containing practical advice upon various aspects of cultivation. But, except that butter is received, graded and frozen free of charge, they have not followed the example of Victoria and South Australia in the direct encouragement of exports. Finally, while the State acts as landlord, banker, and carrier, it also carries on a department of life insurance and annuities, accepts the position of trustee under wills, and, if the programme of the Government is accepted by Parliament, will undertake the business of fire insurance and grant a small allowance to all who are aged and indigent and have resided for a long term of years in the Colony. The development of the resources of the country, under the assistance of the State, has also proceeded in other directions. More than £500,000 had been spent up to March, 1896, in the construction of water-races on goldfields for the benefit of alluvial miners and public companies; and in that year the Premier, in view of the large amount of foreign and native capital that was flowing into the industry, obtained the authorisation of Parliament to the expenditure of a further sum of £200,000 in the conservation of water by means of large reservoirs, the construction of water-races, the extension of prospecting throughout the Colony, and the construction of roads and tracks for the general development of the goldfields. The physical attractions and health resorts of the country, many of which are reached with difficulty, are also being opened up by the expenditure of public funds.

The general question of settlement has, during the last few years, been connected closely with that of the unemployed. In New Zealand, as in several of the Australian Provinces, the construction of the main lines of railway attracted into the country immigrants who, upon their completion, were left without other resources. At the same time the fall in prices rendered many settlers unable to fulfil their obligations, and, upon the loss of their properties, drove them into the towns, where they swelled the ranks of the unemployed. It also forced those who remained solvent to cut down their general expenses, and especially their labour bill, to the lowest possible point. The Government were compelled to face the problem and attempted to give former settlers a fresh chance and gradually to accustom artisans to rural pursuits which, in the case of uncleared land, are at first of a simple character. But the facilities offered under the Land Act were of little use unless it could be arranged that the men, being without capital, should have outside employment upon which they could depend until their lands had been cleared and brought into cultivation. It had already been realised that the construction of roads was an indispensable sequel to that of railways, and large annual appropriations had been made from the Public Works Fund; but it was then decided that settlement should be encouraged systematically in those districts in which it was proposed to proceed with the construction of roads. This policy has, accordingly, been carried out energetically during the last few years from loans and current revenue upon the co-operative system, which was inaugurated in 1891 by the Hon. R. J. Seddon, then Minister of Public Works and now Premier of the Colony. As this system, which was first tried as an experiment upon the railways, is now employed in connection with most public works, its object and operation may be illustrated by a series of quotations: "The contract system had many disadvantages. It gave rise to a class of middle men, in the shape of contractors, who often made large profits out of their undertakings, and at times behaved with less liberality to their workmen than might have been expected under the circumstances. Even in New Zealand, where the labour problem is less acute than in older countries, strikes have occurred in connection with public works contracts, with the result that valuable time has been lost in the prosecution of the works, much capital has been wasted by works being kept at a standstill and valuable plant lying idle, and large numbers of men being for some time unemployed; and considerable bitterness of feeling has often been engendered. The contract system also gave rise to sub-contracting, which is worse again; for not only is it subject to all the drawbacks of the parent system, but by relegating the conduct of the works to contractors of inferior standing, with little or no capital, the evil of "sweating" was admitted. Very often, too, the business people who supplied stores and materials were unable to obtain payment for them, and not seldom the workmen also failed to receive the full amount of their wages. The result in some cases was that, instead of the expenditure proving a great boon to the district in which the works were situated, as would have been the case if the contract had been well managed and properly carried out, such contracts frequently brought disaster in their train. The anomaly of the principal contractor making a large profit, his sub-contractor being ruined and his workmen left unpaid, also occasionally presented itself, and thus the taxpayer who provided the money had the mortification of seeing one man made rich (who would perhaps take his riches to Europe or America to enjoy them) and a number of others reduced to poverty, or in some instances cast upon public charity.... The co-operative system was designed to overcome these evils, and to enable the work to be let direct to the workmen, so that they should be able, not only to earn a fair day's wage for a fair day's work, but also to secure for themselves the profits which a contractor would have otherwise made on the undertaking.... The work is valued by the engineer appointed to have charge of it before it is commenced, and his valuations are submitted to the Engineer-in-Chief of the Colony for approval. When approved, they constitute the contract price for the work; but they are not absolutely unchangeable as in the case of a binding, strictly legal contract. It frequently happens under an ordinary contract that work turns out to be more easy of execution than was anticipated, and the State has to see its contractors making inordinate profits. Sometimes, on the other hand, works cost more than was expected; but in most cases of this kind the contractor either becomes a bankrupt, so that the State has, after all, to pay full value for the work, or, if the contractor happens to be a moneyed man, he will probably find some means of getting relieved of a contract, or of obtaining special consideration for his losses on completion of his work. Under the co-operative system, if it is found that the workmen are earning unusually high rates their contracts can be determined, and be re-let at lower rates, either to the same party of men or to others, as may be necessary. Similarly, if it is shown, after a fair trial of any work, that capable workmen are not able to earn reasonable rates upon it, the prices paid can, with the approval of the Engineer-in-chief, be increased, so long as the department is satisfied that the work is not costing more than it would have cost if let by contract at ordinary fair paying prices.... Another great advantage of co-operation is that it gives the Government complete control over its expenditure. Under the old plan, when large contracts were entered into, the expenditure thereunder was bound to go on, even though, through sudden depression or other unlooked-for shrinking of the revenue, the Government would gladly have avoided or postponed the outlay.... Not only has the Government complete control over the expenditure, but in the matter of the time within which works are to be completed the control is much superior to that possessed when the works are in the hands of a contractor. When once a given time is allowed to a contractor in which to complete a work, any request to finish it in less time would at once provoke a demand for extra payment; but under the co-operative system the Government reserves the right to increase the numbers employed in any party to any extent considered desirable, so that if any sudden emergency arises, or an unusually rapid development in any district takes place, it is quite easy to arrange for the maximum number possible of men being employed on the works in hand, with no more loss of time than is required to get the men together."7

It was at first proposed that the men should work in gangs of about fifty, who should have an equal interest in the contract and make an equal division of the wages and profits; but experience showed that large gangs did not work together harmoniously owing to differences, not only in the temperament of the men, but also in their abilities as workmen. The labourers solved this difficulty by forming themselves into small parties composed of men of about equal ability, with the result that, while some gangs earn higher wages than others, the weak are not excluded altogether from employment. The co-operative works have, on the whole, been successful; but it is clear, from the reports of the surveyors, that constant supervision is necessary, and that there is considerable dissatisfaction, among unskilled workmen, with the low rate of their earnings, and, generally, with the intermittent character of the employment. For the Government have decided, in order that work may be given to as many as possible and that settlement may be promoted, that no labourers shall be employed more than four days in the week. During the remainder of the time, if they have taken up land in the neighbourhood, they devote themselves to it; otherwise they are likely to be demoralised by enforced idleness. The Minister of Public Works attempted to prove that works had been carried out more economically under the co-operative system, but was unable to cite cases that were exactly analogous. He showed that the average number of employés had risen from 788 in 1891-2 to 2,336 in 1895-6, but that, whereas in the former years workmen under the Public Works Department were twice as numerous as those under the Lands Department, in the latter the proportion had been more than reversed. This change must be regarded as satisfactory, as employés under the Lands Department are, in a large majority of cases, settlers.