полная версия

полная версияAustralasian Democracy

The Party first came into prominence at the elections in 1893, when they won fifteen seats out of seventy-two, and have nothing to show in the way of practical legislation to counterbalance the undoubted consolidation of the forces of their opponents. A comparison suggests itself with the success of the Labour Parties in New Zealand and South Australia which have co-operated with progressive Ministers in the enactment of measures of social reform. In the latter case, the Labour Party have been so moderate in their programme, speeches, and actions, that they have carried a quarter of the seats in the Legislative Council, and thus prove themselves not to have alienated the householders and small owners of property who form the bulk of the electorate for that House. In New South Wales the Labour Party have been able, by opportunistic transfers of their votes, to secure electoral reform and the taxation of incomes and land values. The position of affairs in Queensland is not analogous; the coalition of Sir S. Griffith and Sir T. McIlwraith practically destroyed the Opposition, and made it necessary for the Labour Party to trust almost entirely to their own efforts, which should have been directed towards the concentration of all the progressive feeling of the community. Their policy, on the contrary, has deprived them of the support of many who are dissatisfied with the Government, and has not materially strengthened their hold upon the working classes. Though they carried twenty seats in 1896, they only polled 964 more votes than in 1893, nor have they improved their position in the House, as, even should they be supported by the ten Oppositionists and Independents, they would be confronted by a solid phalanx of forty-two Ministerialists. It may be of interest to note that their principal successes have been gained among bushmen and miners, but that they also hold the sugar district of Bundaberg, two agricultural constituencies, two seats at Rockhampton, and three in the poorer and outlying parts of Brisbane.

The complaints of the Labour Party against the Government were directed mainly to their failure to amend the electoral laws or to pass humanitarian legislation, and to the stringency of the Peace Preservation Act of 1894. Apart from their obvious objections to the plural vote of persons holding property in different divisions, they contend that many miners and shearers are permanently disfranchised, as they are neither householders nor reside for six months in the same place, and that persons qualified to be registered are impeded by the provisions which oblige them to fill in a claim in which, among other things, they have to state their qualification, and to get the claim attested by a justice of the peace, electoral registrar, or head male teacher of a State school. The Peace Preservation Act was passed at a time when a serious disturbance had arisen from a strike of shearers in the pastoral districts of the West, on the ground that the ordinary laws of the Colony were insufficient for the prevention, detection, and punishment of crime in such districts, and was as strongly justified by some as it was condemned by others. The Act authorised the Executive to proclaim districts which should come under its operation, and to appoint such district magistrates as might be necessary for carrying its provisions into effect. These may be summarised in the words of the Hon. T. J. Byrnes, the Attorney-General: "The first portion of this legislation is to give us power to put an end to the carrying of arms and the sale of arms in the districts that have been disturbed… It is proposed in the second part of the Bill that inquests on crime may be held… The third portion of the Bill deals with the power of arrest and detention of persons under suspicion." Under the latter heading persons suspected of crime committed in a proclaimed district could be arrested by a special or provisional warrant, in any part of Queensland, and be detained in prison; but it was provided that such persons should be treated as persons accused of crime and not as convicted prisoners, and that no person "should be held in custody under a provisional warrant for a longer period than thirty days, nor under a special warrant for a longer period than two months, without being brought to trial for the offence stated in such warrant." In justification of the measure, the same Minister quoted cases in which woolsheds had been burnt and the police and private individuals had been fired upon although no actual loss of life had occurred. A stranger cannot form an opinion upon the question and can only note, on the one side, that the operation of the Act was limited to one year, that it was most judiciously administered, not more than one district, under a single district magistrate, having been proclaimed, and that it brought about the speedy cessation of the troubles; on the other, that no attempt was made by the Government at mediation between the opposing parties, although, to quote the Attorney-General again, they "knew that labour troubles of an aggravated nature were likely to occur." A Bill "to provide for conciliation in industrial pursuits" is included in the programme of the Government.

As regards the necessity for humanitarian legislation, reference can be made to the evidence given before a Royal Commission in 1891. The Commissioners were unanimous in reporting that, in many factories and workshops which they had visited, the sanitary conditions were very bad, the ventilation was improperly attended to, and little or no attempt had been made to guard the machinery. They were agreed as to the need of further legislation, but, while some were of opinion that the wider powers should be exercised by inspectors under the local authorities, others were in favour of the appointment of a special class of male and female inspectors. They also found that children of the ages of ten, eleven, and twelve years were employed in factories, and that the hours of labour in many retail shops were very long, adding that medical evidence was conclusive that the excessive hours were more injurious to health in Queensland than they would be in a colder climate; but they were unable to concur as to the advisability of legislative interference. A Factory Act, though not of a very stringent character, was passed by the Government towards the end of the session of 1896.

The attention of the Government during the last few years has been directed mainly towards the restoration of the credit of the country and the development of its industries. Queensland reached its lowest ebb in 1889, when, in spite of the recent loan of ten millions, the deficit amounted to £484,000. Since that time matters have rapidly improved, and in 1895 and 1896 the revenue was considerably in excess of the expenditure. This result has been achieved by economical administration, and the direct encouragement of enterprise which has been effected by a large extension of the sphere of State action. The principles involved appear to have been threefold.

First, that the State should facilitate the occupation of outlying districts by the construction of public works, provided they may be expected to return a fair interest upon the expenditure. The proposals put forward some fifteen years ago, that the three Western lines should be connected with the Gulf of Carpentaria by a series of Land Grant Railways, were condemned by the sense of the community, which preferred to postpone their construction until it could be undertaken by the State. In pursuance of this policy all the railways are owned and managed by the State, which has recently protected itself against the danger of the construction of unprofitable lines under political pressure by an Act of Parliament under which, upon any fresh proposal, the local authorities affected may be required to give a guarantee that they will, for a period of years, should the earnings fail to reach a certain standard, make good half of the deficiency out of the rates. In the Western portions of the Colony, in which occupation has been retarded by the scarcity of water, the Government have also incurred considerable expenditure in the successful provision of artesian water and in general works of conservation.

Secondly, that the State may assist producers to dispose advantageously of their produce. Reference has been made to the contracts which the Government have entered into with the British India Company for the carriage of farm and dairy produce. They are now considering the advisability of assisting cattle-owners, whose resources are severely strained by the low prices which they obtain in London for their frozen meat. The principal cause of the low prices and the attitude of the Premier can be gathered from the following extract from the financial statement which he delivered in 1896:—

"Our meat I believe to be as good as any in the world, and the cost at which it can be delivered at a profit at the ports of the Colony will compare favourably with any other country that I am aware of; and yet the prices lately obtainable in London are such as barely cover the charges for freezing, freight, insurance, &c. Something will have to be done if the industry is to be preserved. The only suggestion I have received as yet is that the Colony, either individually or in conjunction with the other Colonies, should take the business of distribution into its own hands, as it is believed that, whilst the consumers give good value for our meat, a great part of that value is absorbed by various graduations of middlemen, leaving, as I have said, a margin for the producer altogether disproportionate to the real value of the product. To effect this a large amount of capital will be required, respecting which I have no proposal to submit, as the matter is really one for private enterprise to undertake, but I mention the matter as one requiring speedy and most serious attention, because, if private enterprise should not be forthcoming to cope with the difficulty, it may devolve upon Parliament to adopt such measures as may appear practicable to conserve an important industry which we can ill afford to lose."

Subsequently, I understand (I was not in Queensland at the time), a Parliamentary Committee was instructed to consider the question, and reported in favour of the establishment at London and in the provinces of depôts for the receipt and distribution of frozen meat.

On another occasion, referring to the injury done to the harbour of Brisbane by excessive towage rates, the Premier said that if private enterprise could not do it for a less sum, it would be a very simple thing for the Government to take the matter in hand.

Thirdly, that the State may use its credit, after strict investigation of the circumstances and upon conviction of the validity of the security, to enable prospective producers to borrow money at a low rate of interest. The Sugar Works Guarantee Act, of which I have quoted the provisions, has led other producers to ask for similar concessions. The farmers want flour mills and cheap money; the pastoralists and graziers complain of the tax levied upon them under the Meat and Dairy Produce Encouragement Acts. Why, they ask, should the sugar industry be exceptionally favoured? Again, if the Government are to establish distributing agencies for frozen meat, why not also for other produce?

The Socialists describe these various measures as a spurious form of socialism calculated to increase the profits of a single class of the community; but the Government do not trouble themselves about abstract terms. They have steadily pursued a settled policy, and have successively assisted the sugar, pastoral, and agricultural interests; they are prepared, if necessary, to give substantial help to cattle-owners in the disposal of their produce, and they intend to propose amendments of the mining laws which will promote the further development of the industry. Nor have the producers alone been benefited; the working classes, who are the first to suffer in times of depression, are sharing in the renewed prosperity of the country, and have been able to take advantage of the increased demand for their services.

IV

THE LAND POLICY OF NEW ZEALAND

Differences of conditions between Australia and New Zealand—The Public Works policy—Taxation on land—The Land Act of 1892—The Land for Settlements Acts—The Government Advances to Settlers Acts—The encouragement of settlement—The co-operative construction of Public Works—The unemployed—Continuity of policy.

The Constitution of 1852, under which New Zealand obtained responsible government, differed from those granted to the Australian Provinces in the creation of Provincial as well as Central Authorities. Owing to the mountainous character of many parts of both islands, and in the absence of railways and other facilities for internal transit, communication had been carried on principally by sea, and settlement, instead of radiating from one point, as in New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia, had been diffused at Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch, Dunedin, and other places of secondary importance. Under these circumstances, while it was deemed advisable to create a Central Government at Auckland, which was transferred to Wellington in 1865, six elective Provincial Councils were established, which, though their legislative and executive powers were confined within specified limits, promoted the continuance of the separate development of the several portions of the Colony. In 1876 the Provincial Legislatures, which had in the meanwhile been increased by a division of territories to ten, were abolished by the Central Government, principally because they impeded the execution of the national policy of the construction of public works. The effects of the system, however, are still seen, especially in the demands made in the House of Representatives that the different districts shall share in the benefits of any proposed expenditure of public funds.

Another feature which served to differentiate New Zealand from Australia was the existence of a warlike native race in the North Island, which opposed the colonisation of the early settlers. From the outset, ignorance of each other's language and habits of thought led to misunderstandings in regard to the disposal of land, which was complicated by the communal tenure of the Maoris. The appreciation of this difficulty led to the insertion in the Treaty of 1840, in which the chiefs purported to cede the sovereignty of New Zealand, of a provision which reserved to the Crown the right of pre-emption over all native lands. But the dissatisfaction was not allayed; the natives, conscious of the steady advances of the settlers and urged to sell by agents of the Crown, feared that they would gradually be dispossessed of their territory. A conflict which arose in regard to some land, and led to fatal results, increased the state of tension, which culminated, after a struggle in the extreme north, in the prolonged conflicts of 1860 to 1870. After the pacification the reciprocal relations began to improve, and are now excellent. The Maoris are universally respected, have four members in the House of Representatives, and two in the Legislative Council, and are represented in the Executive Council by a Minister, who is himself a half-caste. Numerous attempts have also been made to settle the land question, notably by the resumption of the right of pre-emption, which had been waived for a time, and by the constitution, by an Act of 1893, of a Validation Court for the purpose of considering and finally settling the titles to lands obtained by Europeans from the natives. In view of their pre-emptive right, the Government have been bound, in justice to the Maoris, to make provision for the purchase of such lands as may be offered to them, though they have not herein initiated a new policy. From the establishment of Imperial sovereignty to 1870, successive Governments acquired six million acres in the North Island, the whole of the Middle Island, with the exception of reserves for the original owners who were few in number, and Stewart Island. From that date until 1895, another six million acres had been acquired at an outlay of a million and a half pounds, and subsequent purchases, from a large area still under negotiation, amount to about 550,000 acres. New Zealand has thus disbursed, and is still disbursing, large sums of money in the purchase of native lands, while Australia and Tasmania recognised no right of possession on the part of the few degraded aboriginals; and New Zealand alone is burdened with the payment of interest upon loans raised to cover the charges of prolonged military campaigns.

During the wars, settlement was necessarily checked in the North Island, but proceeded in the Middle Island without intermission. At their conclusion, in 1870, Mr. (now Sir Julius) Vogel, the Colonial Treasurer, placed before Parliament a comprehensive scheme of public works, which aimed at the general improvement of means of communication, a matter of particular importance in the North Island as being likely to hasten its final pacification. "The leading features of the policy were: to raise a loan of ten millions, and to spend it over a course of years in systematic immigration, in the construction of a main trunk railway throughout the length of each island, in the employment of immigrants on the railway work, and in their ultimate settlement within large blocks of land reserved near the lines of railway, in the construction of main roads, in the purchase of native lands in the North Island, in the supply of water-power on the goldfields, and in the extension of the telegraph. The plan, with some modifications, was authorised by the Legislature. These modifications mostly related to the amount to be borrowed and to its expenditure; but there was one alteration which crippled the whole policy. The reservation of large tracts of Crown land through which the railways were intended to be made, with a view to the use of that land for settlement thereon, and as the means of recouping to the Colony a great part of the railway expenditure, was withdrawn by the Government from fear of losing the whole scheme. That fear was not unfounded, inasmuch as provincial opposition to the reservation in question, combined with the opposition of those who disliked the whole scheme, would have seriously endangered its existence."5 The provincial opposition was due to the fact that, though the disposal of the Crown lands and the appropriation of the Land Fund were vested by the Constitution Act in the Central Legislature, each province had in practice been allowed to frame the regulations for the alienation of land within its district, and had received the proceeds of sale for its own use. But the omission of the proposed reservation "has necessitated the frequent recurrence of borrowing large sums in order to continue work which had been begun and was useless while it was unfinished, instead of making, as would have been the case under a proper system of land reservation, the work itself to a great extent, if not altogether, self-supporting and self-extending; and that deplorable omission has also frustrated the anticipated conduct of progressive colonisation concurrently with the progress of the railways. The result of not insisting on this fundamental condition has been what should have been foreseen and obviated. The Provincial Governments sold land in the vicinity of the intended railways, and expended the proceeds for provincial purposes; and, as a rule, speculative capitalists absorbed the land and the profits which should have been devoted to colonisation and to the railway fund."6 As the proposed railways would pass through private as well as Crown lands, Sir Julius Vogel also sought the power to levy a special rate, in certain circumstances, upon the persons in the vicinity of the railways who would be benefited by their construction. He believed that he would thereby prevent "indiscriminate scrambling for railways," but was equally unable to induce Parliament to accept his views. The aggregation of large estates was promoted by the low price, 10s. or even 5s. an acre, at which the land was for many years sold. 262 freeholders, including companies, owned in 1891, 7,840,000 acres of land in estates of 10,000 acres and upwards. The Province has, since its foundation, sold or finally disposed of more than 21 million acres, and has at present nearly three million acres open for selection. The remaining lands, exclusive of those in the hands of the Maoris, amount to 16-½ million acres, but comprise large tracts of barren mountainous country in the Middle Island, and of valueless pumice sand in the North Island. In most directions, according to the Premier, settlement is already in advance of the roading operations.

The policy initiated by Sir Julius Vogel in 1870 was carried on by successive Ministers until 1888, during which time more than 27 millions were borrowed and devoted, for the most part, to the construction of railways and other public undertakings. Subsequently, Sir Harry Atkinson and his successor, Mr. John Ballance, realised the danger of constant reliance upon loans, and greatly reduced the expenditure, which had become extravagant in the abundance of borrowed money. Mr. Ballance also reformed the system of direct taxation and gave an impetus to legislation dealing with the settlement of the land and the protection of workmen in industrial pursuits.

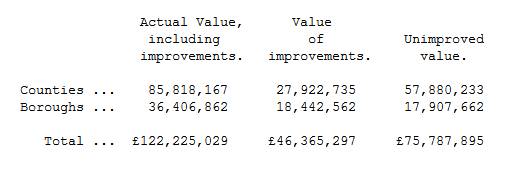

The existing property tax, at the rate of one penny in the £ on all property, subject to an exemption of £500, was replaced by a graduated tax on incomes and land values, the principle of graduation having already been recognised in the case of succession duty. The former impost was naturally upheld by large owners of property and by all classes of professional men who had escaped taxation upon their incomes; while it was distasteful to shopkeepers, who might be taxed on unsaleable merchandise, and to cultivators of the soil, who found that their taxes rose in proportion to the improvements which they effected upon their estates. The Government had little difficulty in passing their measure, which, subject to slight modifications, is in force at the present time. Incomes below £300 are not taxed; between £300 and £1,300 they pay 6d. in the £, above £1,300 a shilling; but the sum of £300 is deducted from the total income in the assessment of the tax. For instance, an income of £2,000 pays £60, at the rate of £25 upon £1,000, and £35 upon £700. The ordinary land-tax is a penny in the £ on all freehold properties of which the unimproved value exceeds £500; between £500 and £1,500 exemption is allowed on £500; between £1,500 and £2,500 the exemption decreases by £1 for every £2 of increased value, being extinguished at the latter amount. Should the value exceed £5,000, a graduated land-tax is also levied, which rises progressively from half a farthing, until it reaches twopence upon estates of the unimproved value of £210,000 and upwards. All improvements are excluded from the assessment of the taxable amount: they are defined to include "houses and buildings, fencing, planting, draining of land, clearing from timber, scrub or fern, laying down in grass or pasture, and any other improvement whatsoever, the benefit of which is unexhausted at the time of valuation." Under this provision rural owners have every encouragement to improve their properties, as the more they do so, the smaller becomes the proportion of the total value of their estates on which they are liable for taxation. Owners are allowed, for the purposes of the ordinary, but not of the graduated land-tax, to deduct from the unimproved value of their land the amount of registered mortgages secured upon it; and mortgagees pay one penny in the £ upon the sum total of their mortgages, but are not subject to the graduated tax. A return, published under the assessment of 1891, shows, however, that rural owners are obtaining less benefit from the exemption of improvements than the owners of urban lands. The figures are as follows:—

It thus appears that land is taxed, on an average, at 49 per cent. of its actual value inclusive of improvements in boroughs, and at 67-½ per cent. in counties; but it must be remembered that, as the urban population is not concentrated in one centre, land values have not been inflated to any great extent, and that much of the rural land has either recently been settled or is held in large blocks in a comparatively unimproved condition. The improvement or sale of such properties would, the Government believed, be promoted by the imposition of the tax. The Minister of Labour (the Hon. W. P. Reeves) expressed this view in the clearest terms: "The graduated tax is a finger of warning held up to remind them that the Colony does not want these large estates. I think that, whether partly or almost entirely unimproved, they are a social pest, an industrial obstacle, and a bar to progress." Similar feelings are, apparently, entertained towards the absentee owner, who, if he has been absent from or resident out of the Province for at least three years prior to the passing of the annual Act imposing the tax, is required to pay an additional 20 per cent. upon the amount of graduated land-tax to which he would otherwise be liable. The income and land taxes produce a revenue about equal to that formerly derived from the property tax, and are collected from far fewer taxpayers, the respective numbers being 15,808 and 26,327 in a population of some 700,000 persons. The benefits have been felt principally by tradesmen, miners, mechanics, labourers, and small farmers. Of 91,500 owners of land, 76,400 escape payment of the land-tax. It may be noted, incidentally, that a permissive Act of 1896 authorises such local bodies as adopt it to levy rates on the basis of the unimproved value of land. Much anxiety has been felt by large landowners and owners of urban property throughout Australasia at the successive adoption of a tax on unimproved values by South Australia, New Zealand, and New South Wales. They fear that it is the first step towards the national absorption of land values advocated by Henry George, but forget that the Governments of New South Wales and New Zealand, in respect of exemptions, and of New Zealand and South Australia, in respect of graduation, have introduced features in their systems of taxation which cause them to be fundamentally distinct from his proposals. The Bill passed through the Victorian Assembly in 1894, but rejected by the Council, also provided for exemptions.