полная версия

полная версияStained Glass Work: A text-book for students and workers in glass

Having laid your sheet of glass down upon the cut-line, place upon it all the bits of glass in their proper places; then take beeswax (and by all means let it be the best and purest you can get; get it at a chemist's, not at the oil-shop), and heat a few ounces of it in a saucepan, and when all of it is melted—not before, and as little after as may be—take any convenient tool, a penknife or a strip of glass, and, dipping it rapidly into the melted wax, convey it in little drops to the points where the various bits of glass meet each other, dropping a single drop of wax at each joint. It is no advantage to have any extra drops along the sides of the bits; if each corner is properly secured, that is all that is needed (fig. 40).

Some people use a little resin or tar with the wax to make it more brittle, so that when the painting is finished and the work is to be taken down again off the plate, the spots of wax will chip off more easily. I do not advise it. Boys in the shop who are just entering their apprenticeship get very skilful, and quite properly so, in doing this work; waxing up yard after yard of glass, and never dropping a spot of wax on the surface.

It is much to be commended: all things done in the arts should be done as well as they can be done, if only for the sake of character and training; but in this case it is a positive advantage that the work should be done thus cleanly, because if a spot of wax is dropped on the surface of the glass that is to be painted on, the spot must be carefully scraped off and every vestige of it removed with a wet duster dipped in a little grit of some kind—pigment does well—otherwise the glass is greasy and the painting will not adhere.

Fig. 40.

For the same reason the wax-saucepan should be kept very clean, and the wax frequently poured off, and all sediment thrown away. A bit of cotton-fluff off the duster is enough to drag a "lump" out on the end of the waxing-tool, which, before you have time to notice it, will be dribbling over the glass and perhaps spoiling it; for you must note that sometimes it is necessary to re-wax down unfired work, which a drop of wax the size of a pinhole, flirted off from the end of the tool, will utterly ruin. How important, then, to be cleanly.

And in this matter of removing such spots from fired work, do please note that you should use the knife and the duster alternately for each spot. Do not scrape a batch of the spots off first and then go over the ground again with the duster—this can only save a second or two of time, and the merest fraction of trouble; and these are ill saved indeed at the cost of doing the work ill. And you are sure to do it so, for when the spot is scraped off it is very difficult to see where it was; you are sure to miss some, in going over the glass with a duster, and you will discover them again, to your cost and annoyance, when you matt over them for the second painting: and, just when you cannot afford to spare a single moment—in some critical process—they will come out like round o's in the middle of your shading, compelling you to break off your work and do now what should have been done before you began to paint.

But the best plan of all is to avoid the whole thing by doing the work cleanly from the first. And it is quite easy; for all you have to do is to carry the tool horizontally till it is over the spot where you want the wax, and then, by a tilt of the hand, slide the drop into its place.

Further Methods of Painting.—There are two chief methods of treating the matt—one is the "stipple," and the other the "film" or badgered matt.

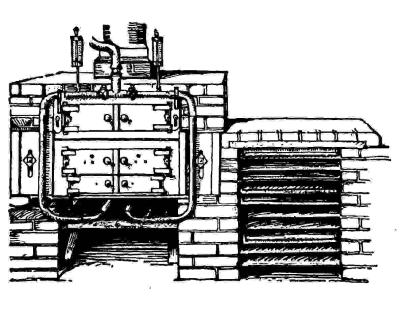

The Stipple.—When you have put on your matt with the camel-hair brush, take a stippling brush (fig. 41) and stab the matt all over with it while it is wet. A great variety of texture can be got in this way, for you may leave off the process at any moment; if you leave it off soon, the work will be soft and blurred, for, not being dry, the pigment will spread again as soon as you leave off: but, if you choose, you can go on stippling till the whole is dry, when the pigment will gather up into little sharp spots like pepper, and the glass between them will be almost clear. You must bear in mind that you cannot use scrubs over work like the last described, and cannot use them to much advantage over stipple at all. You can draw a needle through; but as a rule you do not want to take lights out of stipple, since you can complete the shading in the single process by stippling more or less according to the light and shade you want.

Fig. 41.

A very coarse form of the process is "dry" stippling, where you stipple straight on to the surface of the clear glass, with pigment taken up off the palette by the stippling brush itself: for coarse distant work this may be sometimes useful.

Now as to film. We have spoken of laying on an even matt and badgering it smooth; and you can use this with a certain amount of stipple also with very good effect; but you are to notice one great rule about these two processes, namely, that the same amount of pigment obscures much more light used in film than used in stipple.

Light spreads as it comes through openings; and a very little light let, in pinholes, through a very dark matt, will, at a distance, so assert itself as to prevail over the darkness of the matt.

It is really very little use going on to describe the way the colour acts in these various processes; for its behaviour varies with every degree of all of them. One may gradually acquire the skill to combine all the processes, in all their degrees, upon a single painting; and the only way in which you can test their relative value, either as texture or as light and shade, is to constantly practise each process in all its degrees, and see what results each has, both when seen near at hand and also when seen from a distance. It is useless to try and learn these things from written directions; you must make them your own, as precious secrets, by much practice and much experiment, though it will save you years of both to learn under a good master.

But this question of distance is a most important thing, and we must enlarge upon it a little and try to make it quite clear.

Glass-painting is not like any other painting in this respect.

Let us say that you see an oil-painting—a portrait—at the end of the large room in some big Exhibition. You stand near it and say, "Yes, that is the King" (or the Commander-in-Chief), "a good likeness; however do they do those patent-leather boots?" But after you have been down one side of the room and turn round at the other end to yawn, you catch sight of it again; and still you say, "Yes, it's a good likeness," and "really those boots are very clever!" But if it had been your own painting on glass, and sitting at your easel you had at last said, "Yes,—now it's like the drawing—that's the expression," you could by no means safely count on being able to say the same at all distances. You may say it at ten feet off, at twenty, and yet at thirty the shades may all gather together into black patches; the drawing of the eyelids and eyes may vanish in one general black blot, the half-tones on the cheeks may all go to nothing. These actual things, for instance, will be the result if the cheeks are stippled or scrubbed, and the shade round the eyes left as a film—ever so slight a film will do it. Seen near, you see the drawing through the film; but as you go away the light will come pouring stronger and stronger through the brush or stipple marks on the cheeks, until all films will cut out against it like black spots, altering the whole expression past recognition.

Try this on simple terms:—

Do a face on white glass in strong outline only: step back, and the face goes to nothing; strengthen the outline till the forms are quite monstrous—the outline of the nose as broad as the bridge of it—still, at a given distance, it goes to nothing; the expression varies every step back you take. But now, take a matting brush, with a film so thin that it is hardly more than dirty water; put it on the back of the glass (so as not to wash up your outline); badger it flat, so as just to dim the glass less than "ground glass" is dimmed;—and you will find your outline look almost the same at each distance. It is the pure light that plays tricks, and it will play them through a pinhole.

And now, finally, let us say that you may do anything you can do in the painting of glass, so long as you do not lay the colour on too thick. The outline-touches should be flat upon the glass, and above all things should not be laid on so wet, or laid on so thick, that the pigment forms into a "drop" at the end of the touch; for this drop, and all pigment that is thick upon the glass like that, will "fry" when it is put into the kiln: that is to say, being so thick, and standing so far from the surface of the glass, it will fire separately from the glass itself and stand as a separate crust above it, and this will perish.

Plate IX. shows the appearance of the bubbles or blisters in a bit of work that has fried, as seen under a microscope of 20 diameters; and if you are inclined to disregard the danger of this defect as seen of its natural size, when it is a mere roughness on the glass, what do you think of it now? You can remove it at once by scraping it with a knife; and indeed, if through accident a touch here and there does fry, it is your only plan to so remove it. All you can scrape off should be scraped off and repainted every time the glass comes from the kiln; and that brings us to the important question of firing.

CHAPTER VII

Firing—Three Kinds of Kiln—Advantages and Disadvantages—The Gas-Kiln—Quick Firing—Danger—Sufficient Firing—Soft Pigments—Difference in Glasses—"Stale" Work—The Scientific Facts—How to Judge of Firing—Drawing the Kiln.

The way in which the painting is attached to the glass and made permanent is by firing it in a kiln at great heat, and thus fusing the two together.

Simple enough to say, but who is to describe in writing this process in all its forms? For there is, perhaps, nothing in the art of stained-glass on which there is greater diversity of opinion and diversity of practice than this matter of firing. But let us make a beginning by saying that there are, it may be said, three chief modifications of the process.

First, the use of the old, closed, coke or turf kiln.

Second, of the closed gas-kiln.

And third, of the open gas-kiln.

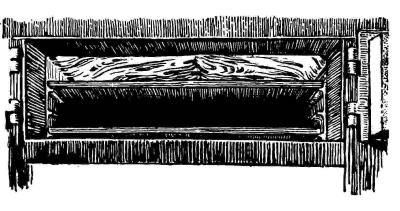

The first consists of a chamber of brick or terra-cotta, in which the glass is placed on a bed of powdered whitening, on iron plates, one above another like shelves, and the whole enclosed in a chamber where the heat is raised by a fire of coke or peat.

This, be it understood, is a slow method. The heat increases gradually, and applies to the glass what the kiln-man calls a "good, soaking heat." The meaning of this expression, of course, is that the gradual heat gives time for the glass and the pigment to fuse together in a natural way, more likely to be good and permanent in its results than a process which takes a twentieth part of the time and which therefore (it is assumed) must wrench the materials more harshly from their nature and state.

There are, it must be admitted, one or two things to be said for this view which require answering.

First, that this form of kiln has the virtue of being old; for in such a thing as this, beyond all manner of doubt, was fired all the splendid stained-glass of the Middle Ages.

Second, that by its use one is entirely preserved from the dangers attached to the misuse of the gas-kiln.

But the answers to these two things are—

First, that the method employed in the Middle Ages did not invariably ensure permanence. Any one who has studied stained-glass must be familiar with cases in which ancient work has faded or perished.

The second claim is answered by the fact, I think beyond dispute, that all objections to the use of the gas-kiln would be removed if it were used properly; it is not the use of it as a process which is in itself dangerous, but merely the misuse of it. People must be content with what is reasonable in the matter; and, knowing that the gas-kiln is spoken of as the "quick-firing" kiln, they must not insist on trying to fire too quick.

Now I have the highest authority (that of the makers of both kiln and pigment) to support my own conviction, founded on my own experience, in what I am here going to say.

Observe, then, that up to the point at which actual fusion commences—that is, when pigment and glass begin to get soft—there is no advantage in slowness, and therefore none in the use of fuel as against gas—no possible disadvantage as far as the work goes: only it is time wasted. But where people go wrong is in not observing the vital importance of proceeding gently when fusion does commence. For in the actual process of firing, when fusion is about to commence, it is indeed all-important to proceed gently; otherwise the work will "fry," and, in fact, it is in danger from a variety of causes. Make it, then, your practice to aim at twenty to twenty-five minutes, instead of ten or twelve, as the period during which the pigment is to be fired, and regulate the amount of heat you apply by that standard. The longer period of moderate heat means safety. The shorter period of great heat means danger, and rather more than danger.

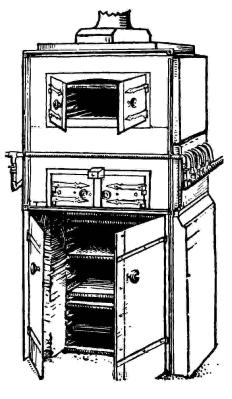

Fig. 42 is the closed gas-kiln, where the glass is placed in an enclosed chamber; fig. 43 is the open gas-kiln, where the gas plays on the roof of the chamber in which the glass lies; fig. 44 shows this latter. But no written description or picture is really sufficient to make it safe for you to use these gas-kilns. You would be sure to have some serious accident, probably an explosion; and as it is absolutely necessary for you to have instruction, either from the maker or the experienced user of them, it is useless for me to tell lamely what they could show thoroughly. I shall therefore leave this essentially technical part of the subject, and, omitting these details, speak of the few principles which regulate the firing of glass.

Fig. 42.

Fig. 43.

Fig. 44.

And the first is to fire it enough. Whatever pigment you use, and with whatever flux, none will be permanent if the work is under-fired; indeed I believe that under-firing is far more the cause of stained-glass perishing than the use of untrustworthy pigment or flux; although it must always be borne in mind that the use of a soft pigment, which will "fire beautifully" at a low heat, with a fine gloss on the surface, is always to be avoided. The pigment is fused, no doubt; but is it united to the glass? What one would like to have would be a pigment whose own fusing-point was the same, or about the same, as that of the glass itself, so that the surface, at least, of the piece of glass softens to receive it and lets it right down into itself. You should never be satisfied with the firing of your glass unless it presents two qualifications: first, that the surface of the glass has melted and begun to run together; and second, that the fused pigment is quite glossy and shiny, not the least dull or rusty looking, when the glass is cool.

"What one would like to have."

And can you not get it?

Well, yes! but you want experience and constant watchfulness—in short, "rule of thumb." For every different glass differs in hardness, and you never know, except by memory and constant handling of the stuff, exactly what your materials are going to do in the kiln; for as to standardising, so as to get the glass into any known relation with the pigment in the matter of fusing, the thing has never, as far as I know, been attempted. It probably could not be done with regard to all, or even many, glasses—nor need it; though perhaps it might be well if a nearer approach to it could be achieved with regard to the manufacture of the lighter tinted glasses, the "whites" especially, on which the heads and hands are painted, and where consequently it is of such vital importance that the painting should have careful justice done to it, and not lose in the firing through uncertainty with regard to conditions.

Nevertheless, if you observe the rule to fire sufficiently, the worst that can happen is a disappointment to yourself from the painting having to an unnecessary extent "fired away" in the kiln. You must be patient, and give it a second painting; and as to the "rule of thumb," it is surprising how one gets to know, by constant handling the stuff, how the various glasses are going to behave in the fire. It was the method of the Middle Ages which we are so apt to praise, and there is much to be said for practical, craftsmanly experience, especially in the arts, as against a system of formulas based on scientific knowledge. It would be a pity indeed to get rid of the accidental and all the delight which it brings, and we must take it with its good and bad.

The second rule with regard to the question of firing is to take care that the work is not "stale" when it goes into the kiln. Every one will tell you a different tale about many points connected with glass, just as doctors disagree in every affair of life. In talking over this matter of keeping the colour fresh—even talking it over with one's practical and experienced friends generally—one will sometimes hear the remark that "they don't see that delay can do it much harm;" and when one asks, "Can it do it any good?" the reply will be, "Well, probably it would be as well to fire it soon;" or in the case of mixing, "To use it fresh." Now, if it would be "as well"—which really means "on the safe side"—then that seems a sufficient reason for any reasonable man.

But indeed I have always found it one of the chiefest difficulties with pupils to get them to take the most reasonable precautions to make quite sure of anything. It is just the same with matters of measurement, although upon these such vital issues depend. How weary one gets of the phrase "it's not far out"—the obvious comment of a reasonable man upon such a remark, of course, being that if it is out at all it's, at any rate, too far out. A French assistant that I had once used always to complain of my demanding (as he expressed it) such "rigorous accuracy." But there are only two ways—to be accurate or inaccurate; and if the former is possible, there is no excuse for the latter.

But as to this question of freshness of colour, which is of such paramount importance, I may quote the same authority I used before—that of the maker of the colour—to back my own experience and previous conviction on the point, which certainly is that fresh colour, used the same day it is ground and fired the same day it is used, fires better and fires away less than any other.

The facts of the case, scientifically, I am assured, are as follows. The pigment contains a large amount of soft glass in a very fine state of division, and the carbonic acid, which all air contains (especially that of workshops), will immediately begin to enter into combination with the alkalis of the glass, throw out the silica, and thus disintegrate what was brought together in the first instance when the glass was made. The result of this is that this intruder (the carbonic acid) has to be driven out again by the heat of the kiln, and is quite likely to disturb the pigment in every possible way in the process of its escape. I have myself sometimes noticed, when some painted work has been laid aside unusually long before firing, some white efflorescence or crystallisation taking place and coming out as a white dust on the painted surface.

Now it is not necessary to know here, in a scientific or chemical sense, what has actually taken place. Two things are evident to common sense. One, that the change is organic, and the other that it is unpremeditated; and therefore, on both grounds, it is a thing to avoid, which indeed my friend's scientific explanation sufficiently confirms. It is well, therefore, on all accounts to paint swiftly and continuously, and to fire as soon as you can; and above all things not to let the colour lie about getting stale on the palette. Mix no more for the day than you mean to use; clean your palette every day or nearly so; work up all the colour each time you set your palette, and do not give way to that slovenly and idle practice that is sometimes seen, of leaving a crust of dry colour to collect, perhaps for days or weeks, round the edge of the mass on your palette, and then some day, when the spirit moves you, working this in with the rest, to imperil the safety of your painting.

How to Know when the Glass is Fired Sufficiently.—This is told by the colour as it lies in the kiln—that is, in such a kiln that you can see the glass; but who can describe a colour? You have nothing for this but to buy your experience. But in kilns that are constructed with a peephole, you can also tell by putting in a bright iron rod or other shining object and holding it over the glass so as to see if the glass reflects it. If the pigment is raw it will (if there is enough of it on the glass to cover the surface) prevent the piece of glass from reflecting the rod; but directly it is fired the pigment itself becomes glossy, and then the surface will reflect.

This is all a matter of practice; nothing can describe the "look" of a piece of glass that is fired. You must either watch batch after batch for yourself and learn by experience, or get a good kiln-man to point out fired and unfired, and call your attention to the slight shades of colour and glow which distinguish one from the other.

On Taking the Glass out of the Fire.—And so you take the glass out of the fire. In the old kilns you take the fire away from the glass, and leave the glass to cool all night or so; in the new, you remove it and leave it in moderate heat at the side of the kiln till it is cool enough to handle, or nearly cold. And then you hold it up and look at it.

CHAPTER VIII

The Second Painting—Disappointment with Fired Work—A False Remedy—A Useful Tool—The Needle—A Resource of Desperation—The Middle Course—Use of the Finger—The Second Painting—Procedure.

And when you have looked at it, as I said just now you should do, your first thought will be a wish that you had never been born. For no one, I suppose, ever took his first batch of painted glass out of the kiln without disappointment and without wondering what use there is in such an art. For the painting when it went in was grey, and silvery, and sharp, and crisp, and firm, and brilliant. Now all is altered; all the relations of light and shade are altered; the sharpness of every brush-mark is gone, and everything is not only "washed out" to half its depth, but blurred at that. Even if you could get it, by a second painting, to look exactly as it was at first, you think: "What a waste of life! I thought I had done! It was right as it was; I was pleased so far; but now I am tired of the thing; I don't want to be doing it all over again."

Well, my dear reader, I cannot tell you a remedy for this state of things—it is one of the conditions of the craft; you must find by experience what pigment, and what glass, and what style of using them, and what amount of fire give the least of these disappointing results, and then make the best of it; and make up your mind to do without certain effects in glass, which you find are unattainable.

There is, however, one remedy which I suppose all glass-painters try, but eventually discard. I suppose we have all passed through the stage of working very dark, to allow for the firing-off; and I want to say a word of warning which may prevent many heartaches in this matter. I having passed through them all, there is no reason why others should. Now mark very carefully what follows, for it is difficult to explain, and you cannot afford to let the sense slip by you.