полная версия

полная версияStained Glass Work: A text-book for students and workers in glass

Christopher Whall

Stained Glass Work: A text-book for students and workers in glass

" … And remembering these, trust Pindar for the truth of his saying, that to the cunning workman—(and let me solemnly enforce the words by adding, that to him only)—knowledge comes undeceitful."

—Ruskin ("Aratra Pentelici")."'Very cool of Tom,' as East thought but didn't say, 'seeing as how he only came out of Egypt himself last night at bed-time.'"

—("Tom Brown's Schooldays").To his Pupils and Assistants, who, if they have learned as much from him as he has from them, have spent their time profitably; and who, if they have enjoyed learning as much as he has teaching, have spent it happily; this little book is Dedicated by their Affectionate Master and Servant,

THE AUTHOR.

EDITOR'S PREFACE

In issuing these volumes of a series of Handbooks on the Artistic Crafts, it will be well to state what are our general aims.

In the first place, we wish to provide trustworthy text-books of workshop practice, from the points of view of experts who have critically examined the methods current in the shops, and putting aside up a standard of quality in the crafts which are more especially associated with design. Secondly, in doing this, we hope to treat design itself as an essential part of good workmanship. During the last century most of the arts, save painting and sculpture of an academic kind, were little considered, and there was a tendency to look on "design" as a mere matter of appearance. Such "ornamentation" as there was was usually obtained by following in a mechanical way a drawing provided by an artist who often knew little of the technical processes involved in production. With the critical attention given to the crafts by Ruskin and Morris, it came to be seen that it was impossible to detach design from craft in this way, and that, in the widest sense, true design is an inseparable element of good quality, involving as it does the selection of good and suitable material, contrivance for special purpose, expert workmanship, proper finish, and so on, far more than mere ornament, and indeed, that ornamentation itself was rather an exuberance of fine workmanship than a matter of merely abstract lines. Workmanship when separated by too wide a gulf from fresh thought—that is, from design—inevitably decays, and, on the other hand, ornamentation, divorced from workmanship, is necessarily unreal, and quickly falls into affectation. Proper ornamentation may be defined as a language addressed to the eye; it is pleasant thought expressed in the speech of the tool.

In the third place, we would have this series put artistic craftsmanship before people as furnishing reasonable occupations for those who would gain a livelihood. Although within the bounds of academic art, the competition, of its kind, is so acute that only a very few per cent. can fairly hope to succeed as painters and sculptors; yet, as artistic craftsmen, there is every probability that nearly every one who would pass through a sufficient period of apprenticeship to workmanship and design would reach a measure of success.

In the blending of handwork and thought in such arts as we propose to deal with, happy careers may be found as far removed from the dreary routine of hack labour as from the terrible uncertainty of academic art. It is desirable in every way that men of good education should be brought back into the productive crafts: there are more than enough of us "in the city," and it is probable that more consideration will be given in this century than in the last to Design and Workmanship.

Our last volume dealt with one of the branches of sculpture, the present treats of one of the chief forms of painting. Glass-painting has been, and is capable of again becoming, one of the most noble forms of Art. Because of its subjection to strict conditions, and its special glory of illuminated colour, it holds a supreme position in its association with architecture, a position higher than any other art, except, perhaps, mosaic and sculpture.

The conditions and aptitudes of the Art are most suggestively discussed in the present volume by one who is not only an artist, but also a master craftsman. The great question of colour has been here opened up for the first time in our series, and it is well that it should be so, in connection with this, the pre-eminent colour-art.

Windows of coloured glass were used by the Romans. The thick lattices found in Arab art, in which brightly-coloured morsels of glass are set, and upon which the idea of the jewelled windows in the story of Aladdin is doubtless based, are Eastern off-shoots from this root.

Painting in line and shade on glass was probably invented in the West not later than the year 1100, and there are in France many examples, at Chartres, Le Mans, and other places, which date back to the middle of the twelfth century.

Theophilus, the twelfth-century writer on Art, tells us that the French glass was the most famous. In England the first notice of stained glass is in connection with Bishop Hugh's work at Durham, of which we are told that around the altar he placed several glazed windows remarkable for the beauty of the figures which they contained; this was about 1175.

In the Fabric Accounts of our national monuments many interesting facts as to mediæval stained glass are preserved. The accounts of the building of St. Stephen's Chapel, in the middle of the fourteenth century, make known to us the procedure of the mediæval craftsmen. We find in these first a workman preparing white boards, and then the master glazier drawing the cartoons on the whitened boards, and many other details as to customs, prices, and wages.

There is not much old glass to be studied in London, but in the museum at South Kensington there are specimens of some of the principal varieties. These are to be found in the Furniture corridor and the corridor which leads from it. Close by a fine series of English coats of arms of the fourteenth century, which are excellent examples of Heraldry, is placed a fragment of a broad border probably of late twelfth-century work. The thirteenth century is represented by a remarkable collection, mostly from the Ste. Chapelle in Paris and executed about 1248. The most striking of these remnants show a series of Kings seated amidst bold scrolls of foliage, being parts of a Jesse Tree, the narrower strips, in which are Prophets, were placed to the right and left of the Kings, and all three made up the width of one light in the original window. The deep brilliant colour, the small pieces of glass used, and the rich backgrounds are all characteristic of mid-thirteenth-century glazing. Of early fifteenth-century workmanship are the large single figures standing under canopies, and these are good examples of English glass of this time. They were removed from Winchester College Chapel about 1825 by the process known as restoration.

W. R. LETHABY.January 1905.

AUTHOR'S PREFACE

The author must be permitted to explain that he undertook his task with some reluctance, and to say a word by way of explaining his position.

I have always held that no art can be taught by books, and that an artist's best way of teaching is directly and personally to his own pupils, and maintained these things stubbornly and for long to those who wished this book written. But I have such respect for the good judgment of those who have, during the last eight years, worked in the teaching side of the art and craft movement, and, in furtherance of its objects, have commenced this series of handbooks, and such a belief in the movement, of which these persons and circumstances form a part, that I felt bound to yield on the condition of saying just what I liked in my own way, and addressing myself only to students, speaking as I would speak to a class or at the bench, careless of the general reader.

You will find yourself, therefore, reader, addressed as "Dear Student." (I know the term occurs further on.) But because this book is written for students, it does not therefore mean that it must all be brought within the comprehension of the youngest apprentice. For it is becoming the fashion, in our days, for artists of merit—painters, perhaps, even of distinction—to take up the practice of one or other of the crafts. All would be well, for such new workers are needed, if it was indeed the practice of the craft that they set themselves to. But too often it is what is called the designing for it only in which they engage, and it is the duty of every one speaking or writing about the matter to point out how fatal is that error.

One must provide a word, then, for such as these also here if one can.

Indeed, to reckon up all the classes to whom such a book as this should be addressed, we should have, I think, to name:– (1) The worker in the ordinary "shop," who is learning there at present, to our regret, only a portion of his craft, and who should be given an insight into the whole, and into the fairyland of design.

(2) The magnificent and superior artist, mature in imagination and composition, fully equipped as a painter of pictures, perhaps even of academical distinction, who turns his attention to the craft, and without any adequate practical training in it, which alone could teach its right principles, makes, and in the nature of things is bound to make, great mistakes—mistakes easily avoidable. No such thing can possibly be right. Raphael himself designed for tapestry, and the cartoons are priceless, but the tapestry a ghastly failure. It could not have been otherwise under the conditions. Executant separated from designer by all the leagues that lie between Arras and Rome.

(3) The patron, who should know something of the craft, that he may not, mistrusting, as so often at present, his own taste, be compelled to trust to some one else's Name, and of course looks out for a big one.

(4) The architect and church dignitary who, having such grave responsibilities in their hands towards the buildings of which they are the guardians, wish, naturally, to understand the details which form a part of their charge. And lastly, a new and important class that has lately sprung into existence, the well-equipped, picked student—brilliant and be-medalled, able draughtsman, able painter; young, thoughtful, ambitious, and educated, who, instead of drifting, as till recently, into the overcrowded ranks of picture-making, has now the opportunity of choosing other weapons in the armoury of the arts.

To all these classes apply those golden words from Ruskin's "Aratra Pentelici" which are quoted on the fly-leaf of the present volume, while the spirit in which I myself would write in amplifying them is implied by my adopting the comment and warning expressed in the other sentence there quoted. The face of the arts is in a state of change. The words "craft" and "craftsmanship," unheard a decade or two ago, now fill the air; we are none of us inheritors of any worthy tradition, and those who have chanced to grope about for themselves, and seem to have found some safe footing, have very little, it seems to me, to plume or pride themselves upon, but only something to be thankful for in their good luck. But "to have learnt faithfully" one of the "ingenuous arts" (or crafts) is good luck and is firm footing; we may not doubt it who feel it strong beneath our feet, and it must be proper to us to help towards it the doubtless quite as worthy or worthier, but less fortunate, who may yet be in some of the quicksands around.

It also happens that the art of stained glass, though reaching to very high and great things, is in its methods and processes a simple, or at least a very limited, one. There are but few things to do, while at the same time the principles of it touch the whole field of art, and it is impossible to treat of it without discussing these great matters and the laws which guide decorative art generally. It happens conveniently, therefore, as the technical part requires less space, that these things should be treated of in this particular book, and it becomes the author's delicate and difficult task to do so. He, therefore, wishes to make clear at starting the spirit in which the task is undertaken.

It remains only to express his thanks to Mr. Drury and Mr. Noel Heaton for help respectively, with the technical and scientific detail; to Mr. St. John Hope for permission to use his reproductions from the Windsor stall-plates, and to Mr. Selwyn Image for his great kindness in revising the proofs.

C. W. WHALL.January 1905.

PART I

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTORY, AND CONCERNING THE RAW MATERIAL

You are to know that stained glass means pieces of coloured glasses put together with strips of lead into the form of windows; not a picture painted on glass with coloured paints.

You know that a beer bottle is blackish, a hock bottle orange-brown, a soda-water bottle greenish-white—these are the colours of the whole substance of which they are respectively made.

Break such a bottle, each little bit is still a bit of coloured glass. So, also, blue is used for poison bottles, deep green and deep red for certain wine glasses, and, indeed, almost all colours for one purpose or another.

Now these are the same glass, and coloured in the same way as that used for church windows.

Such coloured glasses are cut into the shapes of faces, or figures, or robes, or canopies, or whatever you want and whatever the subject demands; then features are painted on the faces, folds on the robes, and so forth—not with colour, merely with brown shading; then, when this shading has been burnt into the glass in a kiln, the pieces are put together into a picture by means of grooved strips of lead, into which they fit.

This book, it is hoped, will set forth plainly how these things are done, for the benefit of those who do not know; and, for the benefit of those who do know, it will examine and discuss the right principles on which windows should be made, and the rules of good taste and of imagination, which make such a difference between beautiful and vulgar art; for you may know intimately all the processes I have spoken of, and be skilful in them, and yet misapply them, so that your window had better never have been made.

Skill is good if you use it wisely and for good end; but craft of hand employed foolishly is no more use to you than swiftness of foot would be upon the broad road leading downwards—the cripple is happier.

A clear and calculating brain may be used for statesmanship or science, or merely for gambling. You, we will say, have a true eye and a cunning hand; will you use them on the passing fashion of the hour—the morbid, the trivial, the insincere—or in illustrating the eternal truths and dignities, the heroisms and sanctities of life, and its innocencies and gaieties?

This book, then, is divided into two parts, of which the intention of one is to promote and produce skilfulness of hand, and of the other to direct it to worthy ends.

The making of glass itself—of the raw material—the coloured glasses used in stained-glass windows, cannot be treated of here. What are called "Antiques" are chiefly used, and there are also special glasses representing the ideals and experiments of enthusiasts—Prior's "Early English" glass, and the somewhat similar "Norman" glass. These glasses, however, are for craftsmen of experience to use: they require mature skill and judgment in the using; to the beginner, "Antiques" are enough for many a day to come.

How to know the Right and Wrong Sides of a Piece of "Antique" Glass.—Take up a sheet of one of these and look at it. You will notice that the two sides look different; one side has certain little depressions as if it had been pricked with a pin, sometimes also some wavy streaks. Turn it round, and, looking at the other side, you still see these things, but blurred, as if seen through water, while the surface itself on this side looks smooth; what inequalities there are being projections rather than depressions. Now the side you first looked at is the side to cut on, and the side to paint on, and it is the side placed inwards when the window is put up.

The reason is this. Glass is made into sheets by being blown into bubbles, just as a child blows soap-bubbles. If you blow a soap-bubble you will see streaks playing about in it, just like the wavy streaks you notice in the glass.

The bubble is blown, opened at the ends, and manipulated with tools while hot, until it is the shape of a drain-pipe; then cut down one side and opened out upon a flattening-stone until the round pipe is a flat sheet; and it is this stone which gives the glass the different texture, the dimpled surface which you notice.

Some glasses are "flashed"; that is to say, a bubble is blown which is mainly composed of white glass; but, before blowing, it is also dipped into another coloured glass—red, perhaps, or blue—and the two are then blown together, so that the red or blue glass spreads out into a thin film closely united to, in fact fused on to, and completely one with, the white glass which forms the base; most "Ruby" glasses are made in this way.

CHAPTER II

Cutting (elementary)—The Diamond—The Wheel—Sharpening—How to Cut—Amount of Force– The Beginner's Mistake—Tapping—Possible and Impossible Cuts—"Grozeing"—Defects of the Wheel—The Actual Nature of a "Cut" in Glass.

No written directions can teach the use of the diamond; it is as sensitive to the hand as the string of a violin, and a good workman feels with a most delicate touch exactly where the cutting edge is, and uses his tool accordingly. Every apprentice counts on spoiling a guinea diamond in the learning, which will take him from one to two years.

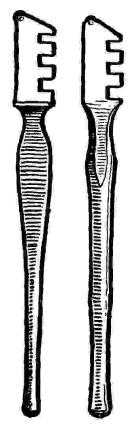

Most cutters now use the wheel, of which illustrations are given (figs. 1 and 2).

Figs. 1 and 2.

The wheels themselves are good things, and cut as well as the diamond, in some respects almost better; but many of the handles are very unsatisfactory. From some of them indeed one might suppose, if such a thing were conceivable, that the maker knew nothing of the use of the tool.

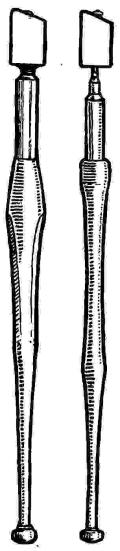

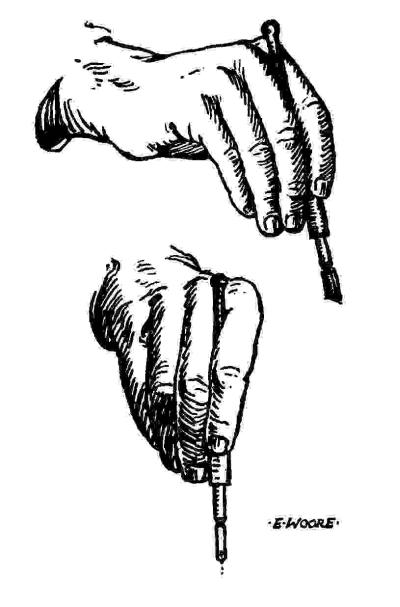

For it is held thus (fig. 5), the pressure of the forefinger both guiding the cut and supplying force for it: and they give you an edge to press on (fig. 1) instead of a surface! In some other patterns, indeed, they do give you the desired surface, but the tool is so thin that there is nothing to grip. What ought to be done is to reproduce the shape of the old wooden handle of the diamond proper (figs. 3 and 4).

Figs. 3 and 4.

The foregoing passage must, however, be amplified and modified, but this I will do further on, for you will understand the reasons better if I insert it after what I had written further with regard to the cutting of glass.

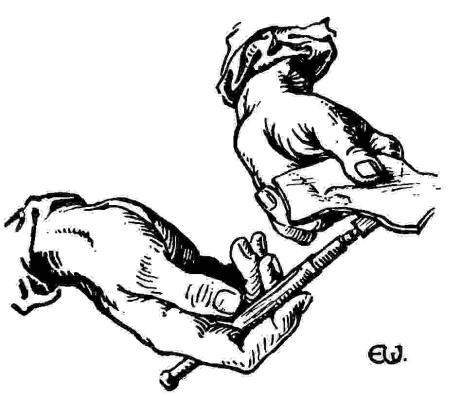

How to Sharpen the Wheel Cutter.—The right way to do this is difficult to describe in writing. You must, first of all, grind down the "shoulders" of the tool, through which the pivot of the wheel goes, for they are made so large that the wheel cannot reach the stone (fig. 6), and must be reduced (fig. 7). Then, after first oiling the pivot so that the wheel may run easily, you must hold the tool as shown in fig. 8, and rub it swiftly up and down the stone. The angle at which the wheel should rest on the stone is shown in fig. 9. You will see that the angle at which the wheel meets the stone is a little blunter than the angle of the side of the wheel itself. You do not want to make the tool too sharp, otherwise you will risk breaking down the edge, when the wheel will cease to be truly circular, and when that occurs it is absolutely useless. The same thing will happen if the wheel is checked in its revolution while sharpening, and therefore the pivot must be kept oiled both for cutting and sharpening.

Fig. 5.

It is a curious fact to notice that the tool, be it wheel or diamond, that is too sharp is not, in practice, found to make so good a cut as one that is less sharp; it scratches the glass and throws up a line of splinters.

Figs. 6 and 7.

Fig. 8.

How to Cut Glass.—Hold the cutter as shown in the illustration (fig. 5), a little sloping towards you, but perfectly upright laterally; draw it towards you, hard enough to make it just bite the glass. If it leaves a mark you can hardly see it is a good cut (fig. 10b), but if it scratches a white line, throwing up glass-dust as it goes, either the tool is faulty, or you are pressing too hard, or you are applying the pressure to the wheel unevenly and at an angle to the direction of the cut (fig. 10a). Not that you can make the wheel move sideways in the cut actually; it will keep itself straight as a ploughshare keeps in its furrow, but it will press sideways, and so break down the edges of the furrow, while if you exaggerate this enough it will actually leave the furrow, and, ceasing to cut, will "skid" aside over the glass. As to pressure, all cutters begin by pressing much too hard; the tool having started biting, it should be kept only just biting while drawn along. The cut should be almost noiseless. You think you're not cutting because you don't hear it grate, but hold the glass sideways to the light and you will see the silver line quite continuous.

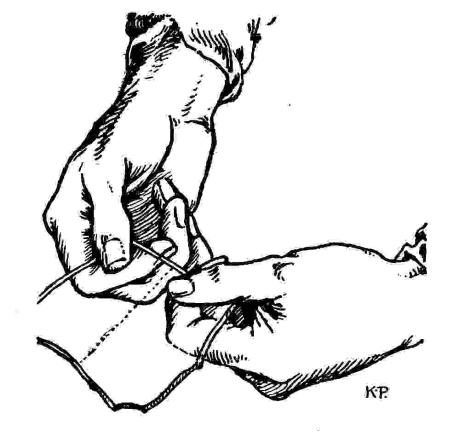

Having made your cut, take the glass up; hold it as in fig. 11, press downward with the thumbs and upward with the fingers, and the glass will come apart.

Fig. 9.

Fig. 10, a and b

Fig. 11.

But you want to cut shaped pieces as well as straight. You cannot break these directly the cut is made, but, holding the glass as in fig. 12, and pressing it firmly with the left thumb, jerk the tool up by little, sharp jerks of the fingers only, so as to tap along the underside of your cut. You will see a little silver line spring along the cut, showing that the glass is dividing; and when that silver line has sprung from end to end, a gentle pressure will bring the glass apart.

Fig. 12.

This upward jerk must be sharp and swift, but must be calculated so as only just to reach the glass, being checked just at the right point, as one hammers a nail when one does not want to stir the work into which the nail is driven. A pushing stroke, a blow that would go much further if the glass were not there, is no use; and for this reason neither the elbow nor the hand must move; the knuckles are the hinge upon which the stroke revolves.

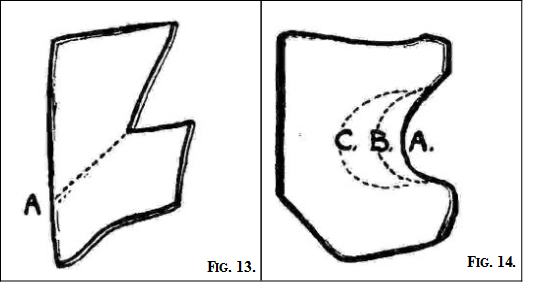

But you can only cut certain shapes—for instance, you cannot cut a wedge-shaped gap out of a piece of glass (fig. 13); however tenderly you handle it, it will split at point A. The nearest you can go to it is a curve; and the deeper the curve the more difficult it is to get the piece out. In fig. 14 A is an average easy curve, B a difficult one, C impossible, except by "groseing" or "grozeing" as cutters call it; that is, after the cut is made, setting to work to patiently bite the piece out with pliers (fig. 15).