полная версия

полная версияStained Glass Work: A text-book for students and workers in glass

Fig. 15.

Now, further, you must understand that you must not cut round all the sides of a shaped piece of glass at once; indeed, you must only cut one side at a time, and draw your cut right up to the edge of the glass, and break away the whole piece which contains the side you are cutting before you go on to another.

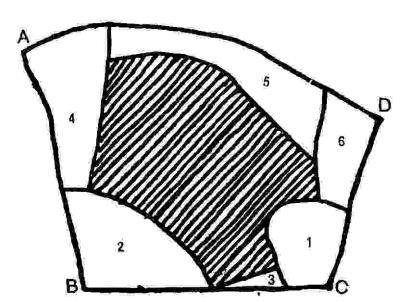

Thus, in fig. 16, suppose the shaded portion to be the shape that you wish to cut out of the piece of glass, A, B, C, D. You must lay your gauge anglewise down upon the piece. Do not try to get the sides parallel to the shapes of your gauge, for that makes it much more difficult; angular pieces break off the easiest.

Fig. 16.

Now, then, cut the most difficult piece first. That marked 1. Perhaps you will not cut it quite true; but, if not, then shift the gauge slightly on to another part of the curve, and very likely it may fit that better and so come true.

Then follow with one of those marked 2 or 3. Probably it would be safest to cut the larger and more difficult piece first, and get both the curved cuts right by your gauge; then you can be quite sure of getting the very easy small bit off quite truly, to fit into its place with both of them. Go on with 4, and then with one of those marked 5 or 6. Probably it would still be best to cut the curved piece first, unless you think that shortening it by cutting off the small corner-piece first will make the curved cut easier by making it shorter.

In any case you must only cut one side at a time, and break it away before you make the cut for another side.

Take care that you do not go back in your cut. You must try and make it quite continuous onwards; for if you go back in the cut, where your tool has already thrown up splinters, it will spoil your tool and spoil your cut also.

Difficult curves, that it is only just possible to get out by groseing, ought never to be resorted to, except for some very sufficient reason. A cartoonist who knows the craft will avoid setting such tasks to the cutter; but, unfortunately, many cartoonists do not know the craft. If people were taught the complete craft as they should be, this book would not have been written.

Here let me say that we cannot possibly within the narrow limits of it go thoroughly into all the very wide range of subjects connected with glass—the chemistry, the permanence, the purity of materials. With the exception of the practice of the craft, probably we shall not be able to go thoroughly into any one of them; but I shall endeavour to mention them all, and to do so sufficiently to indicate the directions in which work and research and experiment may be made, for they are all three much needed in several directions.

It becomes, for instance, now my task, in modifying the passage some pages back as I promised, to go into one of these subjects in the light of inquiries made since the passage in question was written; and I let it for the time being stand just as it was, without the additional information, because it gives a picture of how such things crop up and of the way in which such investigations may be made, and of how useful and pleasant they may be.

Here then let us have—

A LITTLE DISSERTATION UPON CUTTINGThrough the agent for the wheel-cutter in England I communicated with the maker and inventor in America, and told him of our difficulties and perplexities over here, and chiefly with regard to two points. First, the awkwardness of the handle, which causes the glaziers here to use the tool bound round with wadding, or enclosed in a bit of india-rubber pipe; and, secondly, the bluntness of the "jaws" which hold the wheel, and which must be ground down (and are in universal practice ground down), before the tool can be sharpened.

His reply called attention to a number of different patterns of handle, the existence of which, I think, is not generally known, in England at any rate, and some of which seem to more or less meet the difficulties we experience, most of them also being made with malleable iron handles, so that fresh cutting-wheels can be inserted in the same handle. His letter also entered into the question of the actual dynamics of "cutting," maintaining, I think rightly, that a "cut" is made by the edge of the wheel (this not being very sharp) forcing the particles of the glass down into the mass of it by pressure.

With regard to the old-fashioned pattern of tool which we chiefly use in this country, the very sufficient explanation is that they continue to make it because we continue to demand it, a circumstance which, as he declares, is a mystery to the inventor himself! Nevertheless, as we do so, and, in spite of the variety of newer tools on the market, still go on grinding down the jaws of our favourite, and wrapping round the handle with cotton-wool, let us try and put this matter straight, and compare our requirements with the advantages offered us.

There are three chief points to be cleared up. (1) The actual nature of a "cut" in glass; (2) the question of sharpening the tool and grinding down of the jaws to do so; and (3) the "mystery" of our preference for a particular tool, although we all confess its awkwardness by the means we take to modify it.

(1) With regard, then, to the nature of a "cut" in glass I am disposed entirely to agree with the theory put forward by the inventor of the wheel, which an examination of the cuts under the microscope, or even a 6 diameter lens, certainly also tends to confirm.

What happens appears to my non-scientific eyes to be this.

Glass is one of the most fissile or "splittable" of all materials; but it is so just in the same way that ice is, and just in the opposite way to that in which slate or talc is.

Slate or talc splits easily into thin layers or laminæ, because it already lies in such layers, and these will come apart when the force is applied between them: but it will only split into the laminæ of which it already is composed, and along the line of the fissures which already exist between them.

Glass, on the contrary (and the same is true of ice, or for that matter of currant-jelly and such like things), appears to be a substance which is the same in all directions, or nearly so, and therefore as liable to split in one direction as in another, and is so loosely held together that, once a splitting force is applied, the crack spreads very rapidly and easily, and therefore smoothly and in straight lines and in even planes.

The diamond, or the wheel-cutter, is such a force. Being pressed on to the surface, it forces down the particles, and these start a series of small vertical splits, sometimes nearly through the whole thickness of the glass, though invisibly so until the glass is separated. And mark, that it is the starting of the splits that is the important thing; there is no object in making them deep, it is only wasted force; they will continue to split of themselves if encouraged in the proper way (see Plates IX. and X.). Try this as follows.

Take a bit of glass, say 3 inches by 2, and make the very smallest dint you can in it, in the middle of the narrowest dimension. You cannot make one so small that the glass will hold together if you try to break it across. It will break across in a straight line, springing from each end of the tiny cut. The cut may be only 1/8 of an inch long; less—it may be only 1/16, 1/32—as small as you will, the glass will break across just the same.

Why?

Because the cut has started it splitting at each end; and the material being the same all through, the split will go straight on in the direction in which it has started; there is nothing to turn it aside.

So also the pressure of the wheel starts a continuous split, or series of splits, downwards, into the thickness of the glass. No matter how small a distance these go in, the glass will come asunder directly pressure is applied.

Now, if you press too hard in cutting, another thing takes place.

Imagine a quantity of roofing-slates piled flat one on top of another, all the piles being of equal height and arranged in two rows, side by side, so close that the edges of the slates in one row touch the edges of those in the other row, along a central line.

Wheel a wheelbarrow along that line over the edges of both.

What would happen?

The top layer of slates would all come cocking their outer edges up as the barrow passed over their inner ones, would they not?

Now, just so, if you press hard on your glass-cutting wheel, it will press down the edges of the groove, and though there are no layers already made in the glass, the pressure will split off a thin layer from the top surface of the glass on each side in flakes as it goes along (Plate X., d, e).

This is what gives the noise of the cut, c-r-r-r-r-r-; and as the thing is no use the noise is no use; like a good many other things in life, the less noise the better work, much cry generally meaning little wool, as the man found out who shaved the pig.

But the wheel or the diamond is not quite the same as the wheel of the wheelbarrow, for it has a wedge-shaped edge. Imagine a barrow with such a wheel; what then would happen to your slates? besides being cocked up by the wheel, they would also be pushed out, surely?

This happens in glass. You must not imagine that glass is a rigid thing; it is very elastic, and the wedge-like pressure of the wheel pushes it out just as the keel of a boat pushes the water aside in ripples (Plate X., d, e).

All these observations seem to me to bear out the theory of the inventor, and perhaps to some extent to explain it. I am much tempted to carry them further, and ask the questions, why a penknife as well as a wheel will not make a cut in glass, but will make a perfectly definite scratch on it if the glass is placed under water? and why this line so made will yet not serve for separating the glass? and why a piece of glass can be cut in two (roughly, to be sure, but still cut in two) with a pair of scissors under water, a thing otherwise quite impossible?

But I do not think that the knowledge of these questions will help the reader to do better stained-glass windows, and therefore I will not pursue them.

(2) The question of sharpening the tool is soon disposed of.

If the tool is to be sharpened, the jaws must be ground down, whether the maker grinds them down originally or whether we do it. Is sharpening worth while, since the tool only costs a few pence?

Well, it's a question each must decide for himself; but I will just answer two small difficulties which affect the matter.

If grinding the jaws loosens the pivot, it can be hammered tight again with a punch. If sharpening wears out the oil-stone (as it undoubtedly does, and oil-stones are expensive things), a piece of fine polished Westmoreland slate will do as well, and there is no need to be chary of it. Even a piece of ground-glass with oil will do.

(3) But now as to the handle. I am first to explain the amusing "mystery" why the old pattern shown in fig. 1 still sells.

It is because the British working-man is convinced that the wheels in this handle are better quality than any others.

Is he right, or is it only an instance of his love for and faith in the thing he has got used to?

Or can it be that all workmen do not know of the existence of the other types of handle? In case this is so, I figure some (fig. 17). Or is it that the wheel for some reason runs less truly in the malleable iron than in the cast iron?

Fig. 17.

Certain it is that the whole trade here prefers these wheels, and I am bound to say that as far as my experience goes they seem to me to work better than those in other handles.

But as to all the handles themselves, I must now voice our general complaint.

(1) They are too light.

For tapping our heavy antique and slab-glasses we wish we had a heavier tool.

(2) They are too thin in the handle for comfort, at least it seems so to me.

(3) The three gashes cut out of the head of the tool decrease the weight, and if these were omitted the tool would gain. Their only use that I can conceive of is that of a very poor substitute for pliers as a "groseing" tool, if one has forgotten one's pliers. But (as Serjeant Buzfuz might say) "who does forget his pliers?"

The whole question of the handle is complicated by the fact that some cutters rest the tool on the forefinger and some on the middle finger in tapping, and that a handle the sections of which are calculated for the one will not do equally well for the other.

But the whole thing resolves itself into this, that if we could get a tool, the handle of which corresponded in all its curves, dimensions, and sections with the old-established diamond, I think we should all be glad; and if the head, wheel, and pivot were all made of the quality and material of which fig. 1 is now made, but with the handle as I describe, many of us, I think, would be still more glad; and if these remarks lead in any degree to such results, they at least of all the book will have been worth the writing, and will probably be its best claim to a white stone in Israel, as removing one more solecism from "this so-called twentieth century."

I shall now leave this subject of cutting for the present, and describe, up to about the same point, the processes of painting, taking both on to a higher stage later—as if, in fact, I were teaching a pupil; for as soon as you can cut glass well enough to cut a piece to paint on, you should learn to paint on it, and carry the two things on step by step, side by side.

CHAPTER III

Painting (elementary)—Pigments—Mixing—How to Fill the Brush—Outline—Examples—Industry—The Needle and Stick—Completing the Outline.

The pigments for painting on glass are powders, being the oxides of various minerals, chiefly iron. There are others; but take it thus—that the iron oxide is a red pigment, and the others are introduced, mainly, to modify this. The red pigment is the best to use, and goes off less in the firing; but, alas! it is a detestably ugly colour, like red lead; and, do what you will, you cannot use it on white glass. Against clear sky it looks pretty well in some lights, but get it in a sidelight, or at an angle, and the whole window looks like red brick; while, seen against any background except clear sky, it always looks so from all points of view. There are various makers of these pigments. Some glass-painters make their own, and a beginner with any knowledge of chemistry would be wise to work in that direction.

I need not discuss the various kinds of pigment; what follows is a description of my own practice in the matter.

To Mix the Pigment for Painting.—Take a teaspoonful of red tracing-colour, and a rather smaller spoonful of intense black, put them on a slab of thick ground-glass about 9 inches square, and drop clean water upon them till you can work them up into a paste with the palette-knife (fig. 18); work them up for a minute or so, till the paste is smooth and the lumps broken up, and then add about three drops of strong gum made from the purest white gum-arabic dissolved in cold water. Any good chemist will sell this, but its purity is a matter of great importance, for you want the maximum of adhesiveness with the minimum of the material.

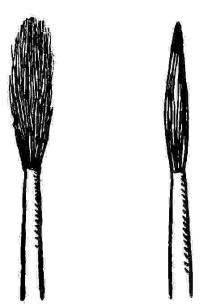

Mix the colour well up with the knife; then take one of those long-haired sable brushes, which are called "riggers" (fig. 19), and which all artists'-colourmen sell, and fill it with the colour, diluting it with enough water to make it quite thin. Do not dilute all the pigment; keep most of it in a tidy lump, merely moist, as you ground it and not further wetted, at the corner of your slab; but always keep a portion diluted in a small "pond" in the middle of your palette.

Fig. 18.

How to Fill the Brush with Pigment.—Now you must note that this is a heavy powder floating free in water, therefore it quickly sinks to the bottom of your little "pond." Each time you fill your brush you must "stir up the mud," for the "mud" is what you want to get in your brush, and not only so, but you want to get your brush evenly full of it from tip to base, therefore you must splay out the hairs flat against the glass, till all are wet, and then in taking it off the palette, "twiddle" it to a point quickly. This takes long to describe, but it does not take a couple of seconds to do. You must have the patience to spend so much pains on it, and even to fill the brush very often, nearly for each touch; then you will get a clear, smooth, manageable stroke for your outline, and save time in the end.

Fig. 19.

How to Paint in Outline.—Make some strokes (fig. 20) on a piece of glass and let them dry; some people like them to stick very tight to the glass, some so that a touch of the finger removes them; you must find which suits you by-and-by, and vary the amount of gum accordingly; but to begin, I would advise that they should be just removable by a moderately hard rub with the finger, rather less hard a rub than you close a gummed envelope with.

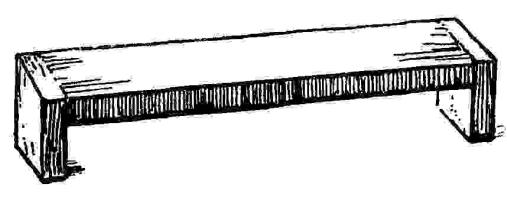

Practise now for a time the making of strokes, large and small, dark and light, broad and fine; and when you have got command of your tools, set yourself the task of doing the same thing, copying an example placed underneath your bit of glass. You will find a hand-rest (fig. 21) an assistance in this.

Fig. 20.

It is difficult to give any list of examples suitable for this stage of glass, but the kind of line employed on the best heraldry is always good for the purpose. The splendid illustrations of this in Mr. St. John-Hope's book of the stall-plates of the Knights of the Garter at Windsor, examples of which by the author's courtesy I am allowed to reproduce (figs. 22-22A), are ideal for bold outline-work, and fascinatingly interesting for their own sake. In most of these there is not only excellent practice in outline, and a great deal of it, but, mixed with it, practice also in flat washes, which it is a good thing to be learning side by side with the other.

Fig. 21.

And here let me note that there are throughout the practice of glass-painting many methods in use at every stage. Each person, each firm of glass-stainers, has his own methods and traditions. I shall not trouble to notice all these as we come to them, but describe what seems to me to be the best practice in each case; but I shall here and there give a word about others.

For instance: if you use sugar or treacle instead of gum, you get a rather smoother-working pigment, and after it is dry you can moisten it as often as you will for further work by merely breathing on the surface; and perhaps if your aim is outline only, it may be well to try it; but if you wish to pass shading-colour over it you must use gum, for you cannot do so over treacle colour; nor do I think treacle serves so well for the next process I am to describe, which here follows.

Fig. 22.

Fig. 22a.

How to complete the Outline better than you possibly can by One Tracing.—When you take up a bit of glass from the table, after having done all you can to make a correct tracing, you will be disappointed with the result. It will have looked pretty well on the table with the copy showing behind it and hiding its defects, but it is a different thing when held up to the searching daylight. This must not, however, discourage you. No one, not the most skilful, could expect to make a perfect copy of an original (if that original had any fineness of line or sensitiveness of touch about it) by merely tracing it downwards on the bench. You must put it upright against the daylight, and mend your drawing, freehand, faithfully by the copy.

These remarks do not, in a great degree, apply to the case of hard outlines specially prepared for literal translation. I am speaking of those where the outline is, in the artistic sense, sensitive and refined, as in a Botticelli painting or a Holbein drawing, and to copy these well you want an easel.

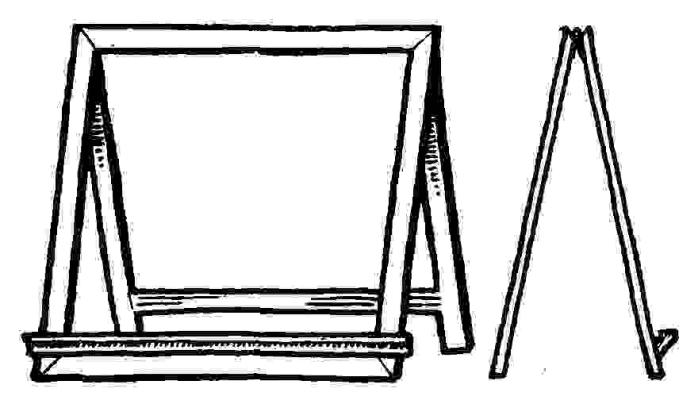

For this small work any kind of frame with a sheet of glass in it, and a ledge to rest your bit of glass on and a leg to stand out behind, will do, and by all means get it made (fig. 23); but do not spend too much on it, for later on you will want a bigger and more complicated thing, which will be described in its proper place—that is to say, when we come to it; and we shallcome to it when we come to deal with work made up of a number of pieces of glass, as all windows must be.

Fig. 23.

This that you have now, not being a window but a bit of glass to practise on, what I have described above will do for it.

A note to be always industrious and to work with all your might.—I advise you to put this work on an easel; but this is not the way such work is usually done;—where the work is done as a task (alas, that it could ever be so!) it is held listlessly in the left hand while touched with the right; but no artist can afford to be at this disadvantage, or at any disadvantage.

Fancy a surgeon having to hold the limb with one hand while he uses the lancet with the other, or an astronomer, while he makes his measurement, bunglingly moving his telescope by hand while he pursues his star, instead of having it driven by the clock!

You cannot afford to be less keen or less in earnest, and you want both hands free—ay! more than this—your whole body free: you must not be lazy and sit glued to your stool; you must get up and walk backwards and forwards to look at your work. Do you think art is so easy that you can afford to saunter over it?

Do, I beg you, dear reader, pay attention to these words; for it is true (though strange) that the hardest thing I have found in teaching has been to get the pupil to take the most reasonable care not to hamper and handicap himself by omitting to have his work comfortably and conveniently placed and his tools and materials in good order. You shall find a man going on painting all day, working in a messing, muddling way—wasting time and money—because his pigment has not been covered up when he left off work yesterday, and has got dusty and full of "hairs"; another will waste hour after hour, cricking his neck and squinting at his work from a corner, when thirty seconds and a little wit would move his work where he would get a good light and be comfortable; or he will work with bad tools and grumble, when five minutes would mend his tools and make him happy.

An artist's work—any artist's, but especially a glass-painter's—should be just as finished, precise, clean, and alert as a surgeon's or a dentist's. Have you not in the case of these (when the affair has not been too serious) admired the way in which the cool, white hands move about, the precision with which the finger-tips take up this or that, and when taken up use it "just so," neither more nor less: the spotlessness and order and perfect finish of every tool and material, from those fearsome things which (though you prefer not to dwell on their uses) you cannot help admiring, down to the snowy cotton-wool daintily poked ready through the holes in a little silver beehive? Just such skill, handling, and precision, and just such perfection of instruments, I urge as proper to painting.