полная версия

полная версияA Company of Tanks

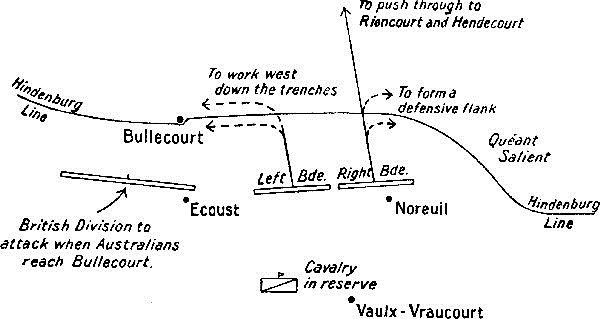

My tanks were detailed to co-operate very closely with the infantry. The right section (Wyatt's) were given three duties: first, to parade up and down the German wire immediately to the right of the front of the attack; second, to remain with the infantry in the Hindenburg Line until the trenches had been successfully "blocked" and the defensive flank secured; third, to accompany the infantry in their advance on Riencourt and Hendecourt.

The centre section (Field's) were required to advance between the two brigades and plunge into the Hindenburg Line. This movement was made necessary by the decision to attack not on a continuous front but up two slight spurs or shoulders. The Hindenburg Line itself lay just beyond the crest of a slope, and these almost imperceptible shoulders ran out from the main slope at right angles to the line. It was thought that the depression between them would be swept by machine-gun fire, and it was decided in consequence to leave the attack up the depression to the tanks alone.

My left section (Swears') were to precede the infantry of the left Australian brigade. They were to obtain a footing in the Hindenburg Line and then work along it into Bullecourt. Whether, later, they would be able to assist the British infantry in their attack on the trenches to the west of Bullecourt was a matter for their discretion.

The atmosphere of the conference was cheerless. It is a little melancholy to revive and rebuild the plan of an attack which has been postponed very literally at the last moment. The conference was an anticlimax. For days and nights we had been completing our preparations. The supreme moment had come, and after hours of acute tension had passed without result. Then again, tired and without spirit, we drew up fresh plans. War is never romantic because emergencies, which might be adventures, come only when the soldier is stale and tired.

We hurried back to the camp at Behagnies and composed fresh orders, while Jumbo re-marked his maps and reshuffled his aeroplane photographs. At dusk Jumbo and I started out in the car for Noreuil, but at Vaulx-Vraucourt we decided to leave the car as the road was impossible. It was heavy with mud and slush and we were far from fresh. We passed Australians coming up and much transport—in places the road was almost blocked. After an hour or more we came to the valley above Noreuil, full of new gun-pits. Our tanks lay hidden against the bank at the side of the road, shrouded in their tarpaulins. My men were busily engaged in making them ready. One engine was turning over very quietly. It was bitterly cold, and the snow still lay on the downs.

We struggled on to a ruined house at the entrance to the village. One room or shed—it may have been a shrine—constructed strongly of bricks, still stood in the middle of the wreckage. This my officers had made their headquarters. I gave instructions for all the officers to be collected, and in the meantime walked through the street to one of the two brigade headquarters in the village.

This brigade was fortunate in its choice, for it lay safe and snug in the bowels of the earth. An old brewery or factory possessed whole storeys of cellars, and the brigade office was three storeys down.

Haigh and Swears were discussing operations with the brigadier. They were all under the illusion that the postponed attack would take place as originally planned, and bitter was the disappointment when I told them that the orders had been changed. I gave the general and his brigade-major a rough outline of the new scheme, and took Swears and Haigh back with me to the ruins.

All my officers were assembled in the darkness. I could not see their faces. They might have been ghosts: I heard only rustles and murmurs. I explained briefly what had happened. One or two of them naturally complained of changes made at such a late hour. They did not see how they could study their orders, their maps, and their photographs in the hour and a half that remained to them before it was time for the tanks to start. So, again, I set out carefully and in detail the exact task of each tank. When I had finished, we discussed one or two points, and then my officers went to their tanks, and I returned to brigade headquarters, so that I might be in touch with the colonel and the Division should anything untoward happen before zero.

The night passed with slow feet, while my tanks were crawling forward over the snow. The brigade-major re-wrote his orders. Officers and orderlies came in and out of the cellar. We had some tea, and the general lay down for some sleep. There was a rumour that one of the tanks had become ditched in climbing out of the road. I went out to investigate, and learned that Morris's tank had been slightly delayed. It was, unfortunately, a clear cold night.

When I returned to the cellar the brigade staff were making ready for the battle. Pads of army signal forms were placed conveniently to hand. The war diary was lying open with a pencil beside it and the carbons adjusted. The wires forward to battalion headquarters were tested. Fresh orderlies were awakened.

Apparently there had been little shelling during the early part of the night. Noreuil itself had been sprinkled continuously with shrapnel, and one or two 5.9's had come sailing over. Forward, the railway embankment and the approaches to it had been shelled intermittently, and towards dawn the Germans began a mild bombardment, but nothing was reported to show that the enemy had heard our tanks or realised our intentions.

I received messages from Haigh that all my tanks were in position, or just coming into position, beyond the railway embankment. Zero hour was immediately before sunrise, and as the minutes filed by I wondered idly whether, deep down in the earth, we should hear the barrage. I was desperately anxious that the tanks should prove an overwhelming success. It was impossible not to imagine what might happen to the infantry if the tanks were knocked out early in the battle. Yet I could not help feeling that this day we should make our name.

We looked at our watches—two minutes to go. We stared at the minute-hands. Suddenly there was a whistling and rustling in the distance, and a succession of little thumps, like a dog that hits the floor when it scratches itself. The barrage had opened. Constraint vanished, and we lit pipes and cigarettes. You would have thought that the battle was over. We had not blown out our matches when there was a reverberating crash overhead. Two could play at this game of noises.

Few reports arrive during the first forty minutes of a battle. Everybody is too busy fighting. Usually the earliest news comes from wounded men, and naturally their experiences are limited. Brigade headquarters are, as a rule, at least an hour behind the battle. You cannot often stand on a hill and watch the ebb and flow of the fight in the old magnificent way.

At last the reports began to dribble in and the staff settled down to their work. There were heavy casualties before the German wire was reached. The enemy barrage came down, hot and strong, a few minutes after zero.... Fighting hard in the Hindenburg trenches, but few tanks to be seen.... The enemy are still holding on to certain portions of the line.... The fighting is very severe.... Heavy counter-attacks from the sunken road at L. 6 b. 5.2. The news is a medley of scraps.

Soon the brigadier is called upon to act. One company want a protective barrage put down in front of them, but from another message it seems probable that there are Australians out in front. The brigadier must decide.

One battalion asks to be reinforced from the reserve battalion. Is it time for the reserve to be thrown into the battle? The brigadier must decide.

They have run short of bombs. An urgent message for fresh supplies comes through, and the staff captain hurries out to make additional arrangements.

There is little news of the tanks. One report states that no tanks have been seen, another that a tank helped to clear up a machine-gun post, a third that a tank is burning.

At last R., one of my tank commanders, bursts in. He is grimy, red-eyed, and shaken.

"Practically all the tanks have been knocked out, sir!" he reported in a hard excited voice.

Before answering I glanced rapidly round the cellar. These Australians had been told to rely on tanks. Without tanks many casualties were certain and victory was improbable. Their hopes were shattered as well as mine, if this report were true. Not an Australian turned a hair. Each man went on with his job.

I asked R. a few questions. The brigade-major was listening sympathetically. I made a written note, sent off a wire to the colonel, and climbed into the open air.

It was a bright and sunny morning, with a clear sky and a cool invigorating breeze. A bunch of Australians were joking over their breakfasts. The streets of the village were empty, with the exception of a "runner," who was hurrying down the road.

The guns were hard at it. From the valley behind the village came the quick cracks of the 18-pdrs., the little thuds of the light howitzers, the ear-splitting crashes of the 60-pdrs., and, very occasionally, the shuddering thumps of the heavies. The air rustled and whined with shells. Then, as we hesitated, came the loud murmur, the roar, the overwhelming rush of a 5.9, like the tearing of a giant newspaper, and the building shook and rattled as a huge cloud of black smoke came suddenly into being one hundred yards away, and bricks and bits of metal came pattering down or swishing past.

The enemy was kind. He was only throwing an occasional shell into the village, and we walked down the street in comparative calm.

When we came to the brick shelter at the farther end of the village we realised that our rendezvous had been most damnably ill-chosen. Fifty yards to the west the Germans, before their retirement, had blown a large crater where the road from Ecoust joins the road from Vaulx-Vraucourt, and now they were shelling it persistently. A stretcher party had just been caught. They lay in a confused heap half-way down the side of the crater. And a few yards away a field-howitzer battery in action was being shelled with care and accuracy.

We sat for a time in this noisy and unpleasant spot. One by one officers came in to report. Then we walked up the sunken road towards the dressing station. When I had the outline of the story I made my way back to the brigade headquarters in the cellar, and sent off a long wire. My return to the brick shelter was, for reasons that at the time seemed almost too obvious, both hasty and undignified. Further reports came in, and when we decided to move outside the village and collect the men by the bank where the tanks had sheltered a few hours before, the story was tolerably complete.

All the tanks, except Morris's, had arrived without incident at the railway embankment. Morris ditched at the bank and was a little late. Haigh and Jumbo had gone on ahead of the tanks. They crawled out beyond the embankment into No Man's Land and marked out the starting-line. It was not too pleasant a job. The enemy machine-guns were active right through the night, and the neighbourhood of the embankment was shelled intermittently. Towards dawn this intermittent shelling became almost a bombardment, and it was feared that the tanks had been heard.9

Skinner's tank failed on the embankment. The remainder crossed it successfully and lined up for the attack just before zero. By this time the shelling had become severe. The crews waited inside their tanks, wondering dully if they would be hit before they started. Already they were dead-tired, for they had had little sleep since their long painful trek of the night before.

Suddenly our bombardment began—it was more of a bombardment than a barrage—and the tanks crawled away into the darkness, followed closely by little bunches of Australians.

On the extreme right Morris and Puttock of Wyatt's section were met by tremendous machine-gun fire at the wire of the Hindenburg Line. They swung to the right, as they had been ordered, and glided along in front of the wire, sweeping the parapet with their fire. They received as good as they gave. Serious clutch trouble developed in Puttock's tank. It was impossible to stop since now the German guns were following them. A brave runner carried the news to Wyatt at the embankment. The tanks continued their course, though Puttock's tank was barely moving, and by luck and good driving they returned to the railway, having kept the enemy most fully occupied in a quarter where he might have been uncommonly troublesome.

Morris passed a line to Skinner and towed him over the embankment. They both started for Bullecourt. Puttock pushed on back towards Noreuil. His clutch was slipping so badly that the tank would not move, and the shells were falling ominously near. He withdrew his crew from the tank into a trench, and a moment later the tank was hit and hit again.

Of the remaining two tanks in this section we could hear nothing. Davies and Clarkson had disappeared. Perhaps they had gone through to Hendecourt. Yet the infantry of the right brigade, according to the reports we had received, were fighting most desperately to retain a precarious hold on the trenches they had entered.

In the centre Field's section of three tanks were stopped by the determined and accurate fire of forward field-guns before they entered the German trenches. The tanks were silhouetted against the snow, and the enemy gunners did not miss.

The first tank was hit in the track before it was well under way. The tank was evacuated, and in the dawning light it was hit again before the track could be repaired.

Money's tank reached the German wire. His men must have "missed their gears." For less than a minute the tank was motionless, then she burst into flames. A shell had exploded the petrol tanks, which in the old Mark I. were placed forward on either side of the officer's and driver's seats. A sergeant and two men escaped. Money, best of good fellows, must have been killed instantaneously by the shell.

Bernstein's tank was within reach of the German trenches when a shell hit the cab, decapitated the driver, and exploded in the body of the tank. The corporal was wounded in the arm, and Bernstein was stunned and temporarily blinded. The tank was filled with fumes. As the crew were crawling out, a second shell hit the tank on the roof. The men under the wounded corporal began stolidly to salve the tank's equipment, while Bernstein, scarcely knowing where he was, staggered back to the embankment. He was packed off to a dressing station, and an orderly was sent to recall the crew and found them still working stubbornly under direct fire.

Swears' section of four tanks on the left were slightly more fortunate.

Birkett went forward at top speed, and, escaping the shells, entered the German trenches, where his guns did great execution. The tank worked down the trenches towards Bullecourt, followed by the Australians. She was hit twice, and all the crew were wounded, but Birkett went on fighting grimly until his ammunition was exhausted and he himself was badly wounded in the leg. Then at last he turned back, followed industriously by the German gunners. Near the embankment he stopped the tank to take his bearings. As he was climbing out, a shell burst against the side of the tank and wounded him again in the leg. The tank was evacuated. The crew salved what they could, and, helping each other, for they were all wounded, they made their way back painfully to the embankment. Birkett was brought back on a stretcher, and wounded a third time as he lay in the sunken road outside the dressing station. His tank was hit again and again. Finally it took fire, and was burnt out.

Skinner, after his tank had been towed over the railway embankment by Morris, made straight for Bullecourt, thinking that as the battle had now been in progress for more than two hours the Australians must have fought their way down the trenches into the village. Immediately he entered the village machine-guns played upon his tank, and several of his crew were slightly wounded by the little flakes of metal that fly about inside a Mk. I. tank when it is subjected to really concentrated machine-gun fire. No Australians could be seen. Suddenly he came right to the edge of an enormous crater, and as suddenly stopped. He tried to reverse, but he could not change gear. The tank was absolutely motionless. He held out for some time, and then the Germans brought up a gun and began to shell the tank. Against field-guns in houses he was defenceless so long as his tank could not move. His ammunition was nearly exhausted. There were no signs of the Australians or of British troops. He decided quite properly to withdraw. With great skill he evacuated his crew, taking his guns with him and the little ammunition that remained. Slowly and carefully they worked their way back, and reached the railway embankment without further casualty.

The fourth tank of this section was hit on the roof just as it was coming into action. The engine stopped in sympathy, and the tank commander withdrew his crew from the tank.

Swears, the section commander, left the railway embankment, and with the utmost gallantry went forward into Bullecourt to look for Skinner. He never came back.

Such were the cheerful reports that I received in my little brick shelter by the cross-roads. Of my eleven tanks nine had received direct hits, and two were missing. The infantry were in no better plight. From all accounts the Australians were holding with the greatest difficulty the trenches they had entered. Between the two brigades the Germans were clinging fiercely to their old line. Counter-attack after counter-attack came smashing against the Australians from Bullecourt and its sunken roads, from Lagnicourt and along the trenches from the Quéant salient. The Australians were indeed hard put to it.

While we were sorrowfully debating what would happen, we heard the noise of a tank's engines. We ran out, and saw to our wonder a tank coming down the sunken road. It was the fourth tank of Swears' section, which had been evacuated after a shell had blown a large hole in its roof.

When the crew had left the tank and were well on their way to Noreuil, the tank corporal remembered that he had left his "Primus" stove behind. It was a valuable stove, and he did not wish to lose it. So he started back with a comrade, and later they were joined by a third man. Their officer had left to look for me and ask for orders. They reached the tank—the German gunners were doing their very best to hit it again—and desperately eager not to abandon it outright, they tried to start the engine. To their immense surprise it fired, and, despite the German gunners, the three of them brought the tank and the "Primus" stove safe into Noreuil. The corporal's name was Hayward. He was one of Hamond's men.

We had left the brick shelter and were collecting the men on the road outside Noreuil, when the colonel rode up and gave us news of Davies and Clarkson. Our aeroplanes had seen two tanks crawling over the open country beyond the Hindenburg trenches to Riencourt, followed by four or five hundred cheering Australians. Through Riencourt they swept, and on to the large village of Hendecourt five miles beyond the trenches. They entered the village, still followed by the Australians....10

What happened to them afterwards cannot be known until the battlefield is searched and all the prisoners who return have been questioned. The tanks and the Australians never came back. The tanks may have been knocked out by field-guns. They may have run short of petrol. They may have become "ditched." Knowing Davies and Clarkson, I am certain they fought to the last—and the tanks which later were paraded through Berlin were not my tanks....

We rallied fifty-two officers and men out of the one hundred and three who had left Mory or Behagnies for the battle. Two men were detailed to guard our dump outside Noreuil, the rescued tank started for Mory, and the remaining officers and men marched wearily to Vaulx-Vraucourt, where lorries and a car were awaiting them.

I walked up to the railway embankment, but seeing no signs of any of my men or of Davies' or Clarkson's tanks, returned to Noreuil and paid a farewell visit to the two brigadiers, of whom one told me with natural emphasis that tanks were "no damned use." Then with Skinner and Jumbo I tramped up the valley towards Vraucourt through the midst of numerous field-guns. We had passed the guns when the enemy began to shell the crowded valley with heavy stuff, directed by an aeroplane that kept steady and unwinking watch on our doings.

Just outside Vaulx-Vraucourt we rested on a sunny slope and looked across the valley at our one surviving tank trekking back to Mory. Suddenly a "5.9" burst near it. The enemy were searching for guns. Then to our dismay a second shell burst at the tail of the tank. The tank stopped, and in a moment the crew were scattering for safety. A third shell burst within a few yards of the tank. The shooting seemed too accurate to be unintentional, and we cursed the aeroplane that was circling overhead.

There was nothing we could do. The disabled tank was two miles away. We knew that when the shelling stopped the crew would return and inspect the damage. So, sick at heart, we tramped on to Vaulx-Vraucourt, passing a reserve brigade coming up hastily, and a dressing station to which a ghastly stream of stretchers was flowing.

We met the car a mile beyond the village, and drove back sadly to Behagnies. When we came to the camp, it was only ten o'clock in the morning. In London civil servants were just beginning their day's work.

The enemy held the Australians stoutly. We never reached Bullecourt, and soon it became only too clear that it would be difficult enough to retain the trenches we had entered. The position was nearly desperate. The right brigade had won some trenches, and the left brigade had won some trenches. Between the two brigades the enemy had never been dislodged. And he continued to counter-attack with skill and fury down the trenches on the flanks—from the sunken roads by Bullecourt and up the communication trenches from the north. In the intervals his artillery pounded away with solid determination. Bombs and ammunition were running very short, and to get further supplies forward was terribly expensive work, for all the approaches to the trenches which the Australians had won were enfiladed by machine-gun fire. Battalions of the reserve brigade were thrown in too late, for we had bitten off more than we could chew; the Germans realised this hard fact, and redoubled their efforts. The Australians suddenly retired. The attack had failed.

A few days later the Germans replied by a surprise attack on the Australian line from Noreuil to Lagnicourt. At first they succeeded and broke through to the guns; but the Australians soon rallied, and by a succession of fierce little counter-attacks drove the enemy with great skill back on to the deep wire in front of the Hindenburg Line. There was no escape. Behind the Germans were belts of wire quite impenetrable, and in front of them were the Australians. It was a cool revengeful massacre. The Germans, screaming for mercy, were deliberately and scientifically killed.

Two of my men, who had been left to guard our dump of supplies at Noreuil, took part in this battle of Lagnicourt. Close by the dump was a battery of field howitzers. The Germans had broken through to Noreuil, and the howitzers were firing over the sights; but first one howitzer and then another became silent as the gunners fell. My two men had been using rifles. When they saw what was happening they dashed forward to the howitzers, and turning their knowledge of the tank 6-pdr. gun to account, they helped to serve the howitzers until some infantry came up and drove back the enemy. Then my men went back to their dump, which had escaped, and remained there on guard until they were relieved on the following day.

The first battle of Bullecourt was a minor disaster. Our attack was a failure, in which the three brigades of infantry engaged lost very heavily indeed; and the officers and men lost, seasoned Australian troops who had fought at Gallipoli, could never be replaced. The company of tanks had been, apparently, nothing but a broken reed. For many months after the Australians distrusted tanks, and it was not until the battle of Amiens, sixteen months later, that the Division engaged at Bullecourt were fully converted. It was a disaster that the Australians attributed to the tanks. The tanks had failed them—the tanks "had let them down."