полная версия

полная версияA Company of Tanks

The majority of the men had wire beds, made by stretching wire-mesh over a wooden frame; but the rooms were draughty. We made a sort of dining-hall in a vast barn, but it was cold and dark.

In these chilly rooms and enormous barns the official supply of fuel did not go far. The coal trains from the "Mines des Marles" often rested for a period in Blangy sidings. I am afraid that this source was tapped unofficially, but the French naturally complained, strict orders were issued, and our fires again were low. It was necessary to act, and to act with decision. I obtained a lorry from the battalion, handed it over to a promising subaltern, and gave him stern instructions to return with much coal. Late in the afternoon he returned, on foot. The lorry had broken down six miles away. Three tons of coal made too heavy a load in frosty weather. The lorry was towed in, and once again we were warm.

I did not ask for details, but a story reached my ears that a subaltern with a lorry had arrived that same morning at a certain Army coal dump. He asked urgently for two tons of coal. The Tanks were carrying out important experiments: coal they must have or the experiments could not be continued. Permission was given at once—he would return with the written order, which the Tanks had stupidly forgotten to give him. A little gift at the dump produced the third ton. To a Heavy Gunner the story needs no comment.

The mess was a dining-hall, medieval in size, with an immense open fireplace that consumed much coal and gave out little heat. We placed a stove in the middle of the hall. The piping was led to the upper part of the fireplace, but in spite of Jumbo's ingenuity it was never secure, and would collapse without warning. The fire smoked badly.

As the hall would seat at least fifty, we specialised in weekly guest-nights, and the reputation of the company for hospitality was unequalled. In those days canteens met all reasonable needs: the allotment system had not been devised; a worried mess-president, commissioned with threats to obtain whisky, was not offered fifty bars of soap in lieu. And we bought a piano that afterwards became famous. Luckily, we had an officer, nicknamed Grantoffski, who could play any known tune from memory.

Our mess was so large that we were asked to entertain temporarily several officers from other units of the Tank Corps in process of formation. Several of these guests came from the central workshops of the Tank Corps at Erin, and later returned our hospitality by doing us small services.

One engineer, who remained with the Tank Corps for a few weeks only, told us a remarkable story. We were talking of revolvers and quick shooting and fighting in America. Suddenly to our amazement he became fierce.

"Do you see my hand? You wouldn't think it, but it's nearly useless—all through a Prussian officer. It was in Louisiana, and he went for me although I was unarmed. I caught his knife with my bare hand—it cut to the bone—I jerked back his wrist and threw him. My pal had a Winchester. He pushed it into the brute's face, smashed it all up, and was just going to pull the trigger when I knocked it away. But the sinews of my hand were cut and there was no doctor there.... I've been after that Prussian ever since. I'm going to get him—oh yes, don't you fear. I'm going to get him. How do I know he is still alive? I heard the other day. He is on the other side. I've pursued him for five years, and now I'm going to get him!"

He was a Scots engineer, a sturdy red-faced fellow with twinkling eyes and a cockney curl to his hair.

The mess was a pleasant place, and training proceeded smoothly, because no company commander ever had better officers. My second-in-command was Haigh, a young and experienced regular from the infantry. He left me after the second battle of Bullecourt, to instruct the Americans. My officers were Swears, an "old Tanker," who was instructing at Bermicourt, Wyatt, and "Happy Fanny," Morris, Puttock, Davies, Clarkson, Macilwaine, Birkett, Grant, King, Richards, Telfer, Skinner, Sherwood, Head, Pritchard, Bernstein, Money, Talbot, Coghlan—too few remained long with the company. Of the twenty I have mentioned, three had been killed, six wounded, three transferred, and two invalided before the year was out.

Training began in the middle of December and continued until the middle of March. Prospective tank-drivers tramped up early every morning to the Tank Park or "Tankodrome"—a couple of large fields in which workshops had been erected, some trenches dug, and a few shell-craters blown. The Tankodrome was naturally a sea of mud. Perhaps the mud was of a curious kind—perhaps the mixture of petrol and oil with the mud was poisonous. Most officers and men working in the Tankodrome suffered periodically from painful and ugly sores, which often spread over the body from the face. We were never free from them while we were at Blangy.

The men were taught the elements of tank driving and tank maintenance by devoted instructors, who laboured day after day in the mud, the rain, and the snow. Officers' courses were held at Bermicourt. Far too few tanks were available for instruction, and very little driving was possible.

"Happy Fanny" toiled in a cold and draughty out-house with a couple of 6-pdrs. and a shivering class. Davies, our enthusiastic Welsh footballer, supervised instruction in the Lewis gun among the draughts of a lofty barn in the Hospice.

The foundation of all training was drill. As a very temporary soldier I had regarded drill as unnecessary ritual, as an opportunity for colonels and adjutants to use their voices and prance about on horses. "Spit and polish" seemed to me as antiquated in a modern war as pipeclay and red coats. I was wrong. Let me give the old drill-sergeant his due. There is nothing in the world like smart drill under a competent instructor to make a company out of a mob. Train a man to respond instantly to a brisk command, and he will become a clean, alert, self-respecting soldier.

We used every means to quicken the process. We obtained a bugle. Our bugler was not good. He became careless towards the middle of his calls, and sometimes he erred towards the finish. He did not begin them always on quite the right note. We started with twenty odd calls a day. Everything the officers and the men did was done by bugle-call. It was very military and quite effective. All movements became brisk. But the bugler became worse and worse. Out of self-preservation we reduced the number of his calls. Finally he was stopped altogether by the colonel, whose headquarters were at the time close to our camp.

Our football team helped to bring the company together. It happened to excel any other team in the neighbourhood. We piled up enormous scores against all the companies we played. Each successive victory made the men prouder of the company, and more deeply contemptuous of the other companies who produced such feeble and ineffective elevens. Even the money that flowed into the pockets of our more ardent supporters after each match strengthened the belief in the superiority of No. 11 Company. The spectators were more than enthusiastic. Our C.S.M. would run up and down the touch-line, using the most amazing and lurid language.

Towards the middle of February our training became more ingenious and advanced. As painfully few real tanks were available for instruction, it was obviously impossible to use them for tactical schemes. Our friendly Allies would have inundated the Claims Officer if tanks had carelessly manœuvred over their precious fields. In consequence the authorities provided dummy tanks.

Imagine a large box of canvas stretched on a wooden frame, without top or bottom, about six feet high, eight feet long, and five feet wide. Little slits were made in the canvas to represent the loopholes of a tank. Six men carried and moved each dummy, lifting it by the cross-pieces of the framework. For our sins we were issued with eight of these abortions.

We started with a crew of officers to encourage the men, and the first dummy tank waddled out of the gate. It was immediately surrounded by a mob of cheering children, who thought it was an imitation dragon or something out of a circus. It was led away from the road to avoid hurting the feelings of the crew and to safeguard the ears and morals of the young. After colliding with the corner of a house, it endeavoured to walk down the side of the railway cutting. Nobody was hurt, but a fresh crew was necessary. It regained the road when a small man in the middle, who had been able to see nothing, stumbled and fell. The dummy tank was sent back to the carpenter for repairs.

We persevered with those dummy tanks. The men hated them. They were heavy, awkward, and produced much childish laughter. In another company a crew walked over a steep place and a man broke his leg. The dummies became less and less mobile. The signallers practised from them, and they were used by the visual training experts. One company commander mounted them on waggons drawn by mules. The crews were tucked in with their Lewis guns, and each contraption, a cross between a fire-engine and a triumphal car in a Lord Mayor's Show, would gallop past targets which the gunners would recklessly endeavour to hit.

Finally, these dummies reposed derelict in our courtyard until one by one they disappeared, as the canvas and the wood were required for ignobler purposes.

We were allowed occasionally to play with real tanks. A sham attack was carried out before hill-tops of generals and staff officers, who were much edified by the sight of tanks moving. The total effect was marred by an enthusiastic tank commander, who, in endeavouring to show off the paces of his tank, became badly ditched, and the tank was for a moment on fire. The spectators appeared interested.

On another day we carried out experiments with smoke-bombs. Two gallant tanks moved slowly up a hill against trenches. When the tanks drew near, the defenders of the trenches rushed out, armed with several kinds of smoke-producing missiles. These they hurled at the tanks, and, growing bolder, inserted them into every loophole and crevice of the tanks. At length the half-suffocated crews tumbled out, and maintained with considerable strength of language that all those who had approached the tanks had been killed, adding that if they had only known what kind of smoke was going to be used they would have loaded their guns to avoid partial asphyxiation.

In addition to these open-air sports, the senior officers of the battalion carried out indoor schemes under the colonel. We planned numerous attacks on the map. I remember that my company was detailed once to attack Serre. A few months later I passed through this "village," but I could only assure myself of its position by the fact that there was some brick-dust in the material of the road.

By the beginning of March the company had begun to find itself. Drill, training, and sport had each done their work. Officers and men were proud of their company, and were convinced that no better company had ever existed. The mob of men had been welded into a fighting instrument. My sergeant-major and I were watching another company march up the street. He turned to me with an expression of slightly amused contempt.

"They can't march like us, sir!"

CHAPTER III.

BEFORE THE FIRST BATTLE.

(March and April 1917.)

In the first months of 1917 we were confident that the last year of the war had come. The Battle of the Somme had shown that the strongest German lines were not impregnable. We had learned much: the enemy had received a tremendous hammering; and the success of General Gough's operations in the Ancre valley promised well for the future. The French, it was rumoured, were undertaking a grand attack in the early spring. We were first to support them by an offensive near Arras, and then we would attack ourselves on a large scale somewhere in the north. We hoped, too, that the Russians and Italians would come to our help. We were told that the discipline of the German Army was loosening, that our blockade was proving increasingly effective, and we were encouraged by stories of many novel inventions. We possessed unbounded confidence in our Tanks.

Late in February the colonel held a battalion conference. He explained the situation to his company commanders and the plan of forthcoming operations.

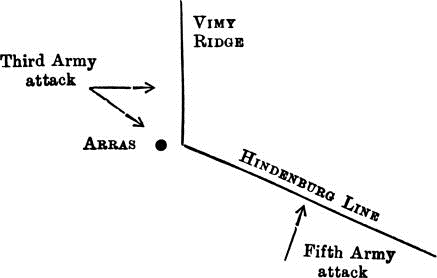

As the result of our successes in the Ancre valley, the German position between the Ancre and Arras formed a pronounced salient. It was determined to attack simultaneously at Arras and from the Ancre valley, with the object of breaking through at both points and cutting off the German inside the salient.

Colonel Elles had offered two battalions of tanks. He was taking a risk. Officers and crews were only half-trained. Right through the period of training real tanks had been too scarce. Improved tanks were expected from England, but none had arrived, and he decided to employ again the old Mark I. tank which had been used in the operations on the Somme in the previous year. The two battalions selected were "C" and "D."

When we examined the orders for the attack in detail, I found that my company was destined to go through with the troops allotted to the second objective and take Mercatel and Neuville Vitasse. It should have been a simple enough operation, as two conspicuous main roads penetrated the German lines parallel with the direction of my proposed attack.

On March 9th I drove to Arras in my car with Haigh, my second-in-command, and Jumbo, my reconnaissance officer. We went by St Pol and the great Arras road. The Arras road is a friend of mine. First it was almost empty except for the lorry park near Savy, and, short of Arras, it was screened because the Germans still held the Vimy Ridge. Then before the Arras battle it became more and more crowded—numberless lorries, convoys of huge guns and howitzers, smiling men in buses and tired men marching, staff-cars and motor ambulances, rarely, a waggon with slow horses, an old Frenchman in charge, quite bewildered by the traffic. When the battle had begun, whole Divisions, stretching for ten miles or more, came marching along it, and the ambulances streamed back to the big hospital at St Pol. I saw it for the last time after the Armistice had been signed, deserted and unimportant, with just a solitary soldier here and there standing at the door of a cottage. It is an exposed and windy road. The surface of it was never good, but I have always felt that the Arras road was proud to help us. It seemed ever to be saying: "Deliver Arras from shell and bomb; then leave me, and I shall be content to dream again."…

We drove into Arras a little nervously, but it was not being shelled, and, hungry after a freezing ride, we lunched at the Hôtel de Commerce.

This gallant hotel was less than 2500 yards from the German trenches. Across the street was a field battery in action. The glass of the restaurant had been broken, the upper stories had been badly damaged, the ceiling of the dining-room showed marks of shrapnel. Arras was being shelled and bombed every night, and often by day; German aeroplanes flew low over the town and fired down the streets. The hotel had still carried on ever since the British had been in Arras and before. The proprietress, a little pinched and drawn, with the inevitable scrap of fur flung over her shoulders, presided at the desk. Women dressed in the usual black waited on us. The lunch was cheap, excellently cooked, and well served—within easy range of the enemy field-guns. After the battle the hotel was put out of bounds, for serving drinks in forbidden hours. Indeed, A.P.M.'s have no souls. It reopened later, and continued to flourish until the German attack of April 1918, when the enemy shelling became too insistent. The hotel has not been badly hit, and, if it be rebuilt, I beseech all those who visit the battlefields of Arras to lunch at the Hôtel de Commerce—in gratitude. It is in the main street just by the station.

We motored out of Arras along a road that was lined with newly-made gun-pits, and, arriving at a dilapidated village, introduced ourselves to the Divisional staff. We discussed operations, and found that much was expected of the tanks. After a cheery tea we drove home in the bitter cold.

On the 13th March we again visited the Division. I picked up the G.S.O. III. of the Division, called on a brigadier, with whom I expected to work, and then drove to the neighbourhood of the disreputable village of Agny. We peeped at the very little there was to be seen of the enemy front line through observation posts in cottages and returned to Arras, where we lunched excellently with the colonel of an infantry battalion. I left Jumbo with him, to make a detailed reconnaissance of the Front....

The Arras battle would have been fought according to plan, we should have won a famous victory, and hundreds of thousands of Germans might well have been entrapped in the Arras salient, if the enemy in his wisdom had not retired. Unfortunately, at the beginning of March he commenced his withdrawal from the unpleasant heights to the north of the Ancre valley, and, once the movement was under way, it was predicted that the whole of the Arras salient would be evacuated. This actually occurred in the following weeks; the very sector I was detailed to attack was occupied by our troops without fighting. Whether the German had wind of the great attack that we had planned, I do not know. He certainly made it impossible for us to carry it out.

As soon as the extent of the German withdrawal became clear, my company was placed in reserve. I was instructed to make arrangements to support any attack at any point on the Arras front.

The Arras sector was still suitable for offensive operations. The Germans had fallen back on the Hindenburg Line, and this complicated system of defences rejoined the old German line opposite Arras. Obviously the most practical way of attacking the Hindenburg Line was to turn it—to fight down it, and not against it. Our preparations for an attack in the Arras sector and on the Vimy Ridge to the north of it were far advanced. It was decided in consequence to carry out with modifications the attack on the German trench system opposite Arras and on the Vimy Ridge. Operations from the Ancre valley, the southern re-entrant of the old Arras salient, were out of the question. The Fifth Army was fully occupied in keeping touch with the enemy.

On the 27th March my company was suddenly transferred from the Third Army to the Fifth Army. I was informed that my company would be attached to the Vth Corps for any operations that might occur. Jumbo was recalled from Arras, fuming at his wasted work, and an advance party was immediately sent to my proposed detraining station at Achiet-le-Grand.

On the 29th March I left Blangy. My car was a little unsightly. The body was loaded with Haigh's kit and my kit and a collapsible table. On top, like a mahout, sat Spencer, my servant. It was sleeting, and there was a cold wind. We drove through St Pol and along the Arras road, cut south through Habarcq to Beaumetz, and plunged over appalling roads towards Bucquoy. The roads became worse and worse. Spencer was just able to cling on, groaning at every bump. Soon we arrived at our old rear defences, from which we had gone forward only ten days before. It was joyous to read the notices, so newly obsolete—"This road is subject to shell-fire"—and when we passed over our old support and front trenches, and drove across No Man's Land, and saw the green crosses of the Germans, the litter of their trenches, their signboards and their derelict equipment, then we were triumphant indeed. Since March 1917 we have advanced many a mile, but never with more joy. Remember that from October 1914 to March 1917 we had never really advanced. At Neuve Chapelle we took a village and four fields, Loos was a fiasco, and the Somme was too horrible for a smile.

On the farther side of the old German trenches was desolation. We came to a village and found the houses lying like slaughtered animals. Mostly they had been pulled down, like card houses, but some had been blown in. It was so pitiful that I wanted to stop and comfort them. The trees along the roads had been cut down. The little fruit-trees had been felled, or lay half-fallen with gashes in their sides. The ploughs rusted in the fields. The rain was falling monotonously. It was getting dark, and there was nobody to be seen except a few forlorn soldiers.

We crept with caution round the vast funnel-shaped craters that had been blown at each cross-road, and, running through Logeast Wood, which had mocked us for so many weeks on the Somme, we came to Achiet-le-Grand.

Ridger, the town commandant, had secured the only standing house, and he was afraid that it had been left intact for some devilish purpose. Haigh and Grant of my advance party were established in a dug-out. So little was it possible in those days to realise the meaning of an advance, that we discovered we had only two mugs, two plates, and one knife between us.

In the morning we got to work. A supply of water was arranged for the men; there was only one well in the village that had not been polluted. We inspected the ramp by which the tanks would detrain, selected a tankodrome near the station, wired in a potential dump, found good cellars for the men, and began the construction of a mess in the remains of a small brick stable. Then Haigh and I motored past the derelict factory of Bihucourt and through the outskirts of Bapaume to the ruins of Behagnies, on the Bapaume-Arras road. After choosing sites for an advanced camp and tankodrome, we walked back to Achiet-le-Grand across country, in order to reconnoitre the route for tanks from the station to Behagnies. After lunch, Haigh, Jumbo, and I motored to Ervillers, which is beyond Behagnies, and, leaving the car there, tramped to Mory. Jumbo had discovered in the morning an old quarry, hidden by trees, that he recommended as a half-way house for the tanks, if we were ordered to move forward; but the enemy was a little lively, and we determined to investigate further on a less noisy occasion.

That night we dined in our new mess. We had stretched one tarpaulin over what had been the roof, and another tarpaulin took the place of an absent wall. The main beam was cracked, and we feared rain, but a huge blazing fire comforted us—until one or two slates fell off with a clatter. We rushed out, fearing the whole building was about to collapse. It was cold and drizzling. We stood it for five minutes, and then, as nothing further happened, we returned to our fire....

In some general instructions I had received from the colonel, it was suggested that my company would be used by the Vth Corps for an attack on Bullecourt and the Hindenburg Line to the east and west of the village. It will be remembered that the attack at Arras was designed to roll up the Hindenburg Line, starting from the point at which the Hindenburg Line joined the old German trench system. General Gough's Fifth Army, consisting of General Fanshawe's Vth Corps and General Birdwood's Corps of Australians, lay south-east of Arras and on the right of the Third Army. The Fifth Army faced the Hindenburg Line, and, if it attacked, it would be compelled to attack frontally.

The disadvantages of a frontal attack on an immensely strong series of entrenchments were balanced by the fact that a successful penetration would bring the Fifth Army on the left rear of that German Army, which would be fully occupied at the time in repelling the onset of our Third Army.

The key to that sector of the Hindenburg Line which lay opposite the Fifth Army front was the village of Bullecourt.

In the last week of March the Germans had not taken refuge in their main line of defence, and were still holding out in the villages of Croisilles, Ecoust, and Noreuil.

We were attacking them vigorously, but with no success and heavy casualties. On the morning of the 31st March Jumbo and I drove again to Ervillers and walked to Mory, pushing forward down the slope towards Ecoust. There was a quaint feeling of insecurity, quite unjustified, in strolling about "on top." We had an excellent view of our shells bursting on the wire in front of Ecoust, but we saw nothing of the country we wanted to reconnoitre—the approaches to Bullecourt. Ecoust was finally captured at the sixth or seventh attempt by the 9th Division on April 1st.