полная версия

полная версияA Company of Tanks

The Australians, in the bitterness of their losses, looked for scapegoats and found them in my tanks, but my tanks were not to blame. I have heard a lecturer say that to attack the Hindenburg Line on a front of fifteen hundred yards without support on either flank was rash. And it must not be forgotten that the attack ought to have been, and in actual fact was, expected. The artillery support was very far from overwhelming, and the barrage, coming down at zero, gave away the attack before my tanks could cross the wide No Man's Land and reach the German trenches.

What chances of success the attack possessed were destroyed by the snow on the ground, the decision to leave the centre of the attack to the tanks alone, the late arrival of the reserve brigade, and the shortage of bombs and ammunition in the firing line. These unhappy circumstances fitted into each other. If the snow had not made clear targets of the tanks, the tanks by themselves might have driven the enemy out of their trenches in the centre of the attack. If the first stages of the attack had been completely successful, the reserve brigade might not have been required. If the Australians had broken through the trench system on the left and in the centre, as they broke through on the left of the right brigade, bombs would not have been necessary.

It is difficult to estimate the value of tanks in a battle. The Australians naturally contended that without tanks they might have entered the Hindenburg Line. I am fully prepared to admit that the Australians are capable of performing any feat, for as storm troops they are surpassed by none. It is, however, undeniable that my tanks disturbed and disconcerted the enemy. We know from a report captured later that the enemy fire was concentrated on the tanks, and the German Higher Command instanced this battle as an operation in which the tanks compelled the enemy to neglect the advancing infantry. The action of the tanks was not entirely negative. On the right flank of the right brigade, a weak and dangerous spot, the tanks enabled the Australians to form successfully a defensive flank.

The most interesting result of the employment of tanks was the break-through to Riencourt and Hendecourt by Davies' and Clarkson's tanks, and the Australians who followed them. With their flanks in the air, and in the face of the sturdiest opposition, half a section of tanks and about half a battalion of infantry broke through the strongest field-works in France and captured two villages, the second of which was nearly five miles behind the German line. This break-through was the direct forefather of the break-through at Cambrai.

My men, tired and half-trained, had done their best. When General Elles was told the story of the battle, he said in my presence, "This is the best thing that tanks have done yet."

The company received two messages of congratulation. The first was from General Gough—

"The Army Commander is very pleased with the gallantry and skill displayed by your company in the attack to-day, and the fact that the objectives were subsequently lost does not detract from the success of the tanks."

The second was from General Elles—

"The General Officer Commanding Heavy Branch M.G.C. wishes to convey to all ranks of the company under your command his heartiest thanks and appreciation of the manner in which they carried out their tasks during the recent operations, and furthermore for the gallantry shown by all tank commanders and tank crews in action."

The company gained two Military Crosses, one D.C.M., and three Military Medals in the first Battle of Bullecourt.

CHAPTER V.

THE SECOND BATTLE OF BULLECOURT.

(May 3, 1917.)

When the First Battle of Bullecourt had been fought in the office as well as in the field, when all the returns and reports had been forwarded to the next higher authority, and all the wise questions from the highest authority had been answered yet more wisely, we obtained lorries and made holiday in Amiens.

It was my first visit, and I decided whenever possible to return. It rained, but nobody minded. We lunched well at the Restaurant des Huîtres in the Street of the Headless Bodies. It was a most pleasant tavern—two dainty yellow-papered rooms over a mean shop. The girls who waited on us were decorative and amusing, the cooking was magnificent, and the Chambertin was satisfying. Coming from the desolate country we could not want more. We tarried as long as decorum allowed, and then went out reluctantly into the rain to shop. We bought immense quantities of fresh vegetables—cauliflowers, Brussels sprouts, new potatoes, and a huge box of apples, also a large "paté de canard," as recommended by Madame de Sévigné. A shampoo enabled us to consume chocolate and cakes. We put our last packages in the car and drove back in the evening.

At Behagnies we made ourselves comfortable, now that the strain was removed of preparing against time for a battle. Our tents mysteriously increased and multiplied. Odd tarpaulins were fashioned into what were officially termed "temporary structures." My orderly-room was cramped. I gave a willing officer the loan of a lorry, and in the morning I found an elaborate canvas cottage "busting into blooth" under the maternal solicitude of my orderly-room sergeant. The piano, which for several days was ten miles nearer the line than any other piano in the district, was rarely silent in the evenings. Only a 6-inch gun, two hundred yards from the camp, interrupted our rest and broke some of our glasses. It was fine healthful country of downs and rough pasture. We commandeered horses from our troop of Glasgow Yeomanry, and spent the afternoons cantering gaily. Once I went out with the colonel, who was riding the famous horse that had been with him through Gallipoli, but to ride with an international polo-player has its disadvantages. Luckily, my old troop-horse was sure-footed enough, and if left to his own devices even clambered round the big crater in the middle of Mory.

A few days after the first battle, Ward's11 company detrained at Achiet-le-Grand and trekked to Behagnies. They came from the Canadians at Vimy Ridge, and were full of their praises. The Canadians left nothing to chance. Trial "barrages" were put down, carefully watched and "thickened up" where necessary. Every possible plan, device, or scheme was tried—every possible preparation was made. The success of the attack was inevitable, and the Germans, whose aeroplanes had been busy enough, found their way to the cages without trouble, happy to have escaped.

Ward's company, filled with the unstinted rations of the Canadians, who had thought nothing of giving them a few extra sheep, were gallant but unsuccessful. The ground was impossible and the tanks "ditched." They were dug out, hauled out, pulled out, one way or another under a cruel shelling, but they never came into the battle. It was naturally a keen disappointment to Ward, and he and his company at Behagnies were spoiling for a fight.

The third company of the battalion under Haskett-Smith had been fighting in front of Arras with great dash and astonishingly few casualties. "No. 10" was a lucky company, and deserved its luck, until the end of the war. In sections and in pairs the tanks had helped the infantry day after day. At Telegraph Hill they had cleared the way, and again near Heninel. The company was now resting at Boiry, and we drove over to see Haskett-Smith and congratulate him on his many little victories.

It will be remembered that there were two phases to the battle of Arras. In the first phase we gained success after success. The enemy wavered and fell back. At Lens he retired without cause. Then his resistance began to stiffen, and we were fought to a standstill. Men and guns were brought by the enemy from other parts of the front, and the German line became almost as strong as it had been before the battle, while we were naturally handicapped by the difficulty of bringing up ammunition and supplies over two trench systems and a battlefield. In the second phase we attacked to keep the Germans busy, while the French hammered away without much success away to the south. This second phase was infinitely the deadlier. We made little headway, and our casualties were high. We had not yet begun our big attack of the year. We were losing time and losing men.

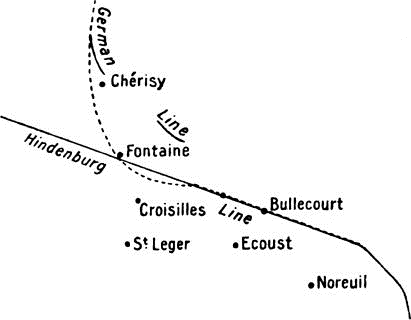

The left flank of the German Armies engaged rested on the Hindenburg Line. As the Germans retired, their left flank withdrew down the Hindenburg Line, until, at the end of April, it rested on the Hindenburg Line at Fontaine-lez-Croisilles. West of Fontaine the Hindenburg Line was ours, and east of it German.

Ward's company and mine were concerned with the "elbow" from Chérisy to Bullecourt. Ward's company was detailed to renew the attack on Bullecourt, and a section of mine under Haigh was allotted to the Division which was planning to attack Fontaine itself. At first it was decided to clear the Hindenburg Line in front of Fontaine by a preliminary operation, but the picture of two lone tanks working down the trenches in full view of German gunners on higher ground did not appeal to the colonel, and nothing came of it. The grand attack, the Second Battle of Bullecourt, was scheduled for May 3rd.

On 29th April Cooper and I went reconnoitring. It was a blazing hot day, with just enough wind. First we drove to St Leger—a pleasant half-ruined village, surrounded by German horse lines under the trees, where the Glasgow Yeomanry had been badly shelled in the days before the first battle, when we were attacking Croisilles and Ecoust. We visited Haigh's section, who had come up overnight from Behagnies,—they were snugly hidden under the railway embankment,—then, putting on our war-paint, we strolled up the hill to the right. It was most open warfare for the guns. They were drawn up on the reverse side of the hill, with no particular protection. Most of them were firing. The gun crews who were not on duty were sitting in the sun smoking or kicking a football about.

Further back our big guns were carrying out a sustained bombardment, and in the course of it experimenting with "artillery crashes," at that time a comparatively new form of "frightfulness." There is some particular point, an emplacement, or perhaps an observation post, which you want to destroy utterly and without question. Instead of shelling it for a morning with one or two guns, you concentrate on it every gun and howitzer that will bear, and carefully arrange the timing, so that all the shells arrive together. It is extravagant but effective—like loosing off a ship's broadside. The noise of the shells as they come all together through the air, whining and grumbling loudly and more loudly, is wonderfully exhilarating. We employed the "artillery crash" in the Loos salient with the 16th Division during the summer of '16, but we had not too many shells then.

The Germans were firing little and blindly as we struck across to the Hindenburg Line, having planned to walk alongside it, as far as we might, down towards Fontaine. The enemy, however, suddenly conceived a violent dislike to their old trenches and some batteries near. So we dropped first into a shell-hole, and then, jumping into the trench, found a most excellent concrete machine-gun emplacement, where we sat all at our ease and smoked, praising the careful ingenuity of the German engineer.

We saw much from a distance, but little near, and returned along the upper road by Mory Copse.

Cooper and I made another expedition on the 30th, driving to Heninel and walking up the farther side of the Hindenburg Line. We pushed forward to the ridge above Chérisy and Fontaine, but we could see little of the enemy lines on account of the convexity of the slope. Gunner officers were running about like ants searching for positions and observation posts.

On the way back to the car we were resting and looking at our maps when we saw a characteristic example of the iron nerves of the average soldier. A limbered waggon was coming along a rough track when a small shell burst on the bank a few yards behind the waggon. Neither the horses nor the drivers turned a hair. Not the slightest interest was taken in the shell. It might never have burst.

On the night of the first of May Haigh's section moved forward from St Leger. The night had its incidents. Mac's baggage rolled on to the exhaust-pipe and caught fire,—it was quickly put out and no harm done, except to the baggage. The tanks stealthily crossed the Hindenburg Line by an old road and crept to the cover of a bank. Close by was a large clump of "stink" bombs, Very lights, and similar ammunition. Just as the first tanks were passing a shell exploded the dump. It was a magnificent display of deadly fireworks, and the enemy, as usual, continued to shell the blaze. There is no spot on earth quite so unpleasant as the edge of an exploding dump. Boxes of bombs were hurtling through the air and exploding as they fell. Very lights were streaming away in all directions. "Stink" bombs and gas bombs gave out poisonous fumes. Every minute or two a shell dropping close added to the uproar and destruction. With great coolness and skill the crews, led and inspired by Haigh, brought their tanks past the dump without a casualty.

Mac's tank had been delayed by the burning of his kit. When he arrived on the scene the pandemonium had died down, and the great noisy bonfire was just smouldering. Mac's tank came carefully past, when suddenly there was a loud crackling report. A box of bombs had exploded under one of the tracks and broken it. There was nothing to be done except send post-haste for some new plates and wait for the dawn.

When, on the afternoon of the 2nd, the colonel and I went up to see Haigh, the mechanics were just completing their work, and Mac's tank was ready for the battle a few hours after the plates had arrived.

Ward had moved his tanks forward to Mory Copse, where we had hidden ourselves before the trek through the blizzard to the valley above Noreuil. He was to work with the division detailed to attack the stronghold of Bullecourt. The front of the grand attacks had widened. On the 3rd of May the British armies would take the offensive from east of Bullecourt to distant regions north of the Scarpe. This time the Australians were without tanks.

I had given Haigh a free hand to arrange what he would with the brigade to which he was attached, and, not wishing to interfere with his little command, I determined to remain at Behagnies until the battle was well under way, and content myself with a scrutiny of his plans.

It was agreed that his section should "mother" the infantry, who were attacking down the Hindenburg Line, by advancing alongside the trenches and clearing up centres of too obstinate resistance. I endeavoured to make it quite clear to the divisional commander that no very great help could be expected from a few tanks operating over ground broken up by a network of deep and wide trenches.

At 3.45 A.M. the barrage woke me. I might perhaps have described the tense silence before the first gun spoke, and the mingled feelings of awe, horror, and anxiety that troubled me; but my action in this battle was essentially unheroic. Knowing that I should not receive any report for at least an hour, I cursed the guns in the neighbourhood, turned over and went to sleep.

The first messages began to arrive about 5.30 A.M. All the tanks had started to time. There was an interval, and then real news dribbled in. The Australians had taken their first objective—the front trench of the Hindenburg system. We had entered the trenches west of Bullecourt. Soon aeroplane reports were being wired through from the army. A tank was seen here in action; another tank was there immobile. Two tanks had reached such-and-such a point.

With what tremulous excitement the mothers and fathers and wives of the crews would have seized and smoothed out these flimsy scraps of pink paper! "Tank in flames at L. 6. d. 5. 4." That might be Jimmy's tank. No, it must be David's! Pray God the airman has made a mistake! We, who had set the stage, had only to watch the play. We could not interfere. Report after report came in, and gradually we began, from one source or another, to build up a picture of the battle.

The division attacking Bullecourt could not get on. Furious messages came back from Ward. His tanks were out in front, but the infantry "could not follow." His tanks were working up and down the trenches on either side of Bullecourt. One tank had found the Australians and was fighting with them. Tanks went on, returned, and went forward again with consummate gallantry, but the infantry could not get forward. They would advance a little way, and then, swept by machine-gun fire, they would dig in or even go back.

One of his officers, commonly known as "Daddy," was sent back in Ward's car. "Daddy" was dirty, unshorn, and covered with gore from two or three wounds. He was offered breakfast or a whisky-and-soda, and having chosen both, told us how he had found himself in front of the infantry, how the majority of his crew had been wounded by armour-piercing bullets, how finally his tank had been disabled and evacuated by the crew, while he covered their withdrawal with a machine-gun.

These armour-piercing bullets caused many casualties that day. We were still using the old Mark I. Tank, which had fought on the Somme, and the armour was not sufficiently proof.

Bullecourt remained untaken, though the Australians clung desperately to the trenches they had won. The British infantry returned to the railway embankment. The attack had not been brilliant. It required another division to reach the outskirts of the village, but the division which failed on the 3rd of May became a brilliant shock-division under other circumstances, just as "Harper's Duds" became the most famous division in France.

Ward's company was lucky. Several of his tanks "went over" twice, one with a second crew after all the men of the first crew had been killed or wounded. The majority of his tanks rallied, and only one, the tank which had fought with the Australians, could not be accounted for when Ward, wrathful but undismayed, returned to battalion headquarters at Behagnies.

Meanwhile little news had come from Haigh. Twice I motored over to the headquarters of the division with which his tanks were operating, but on each occasion I heard almost nothing. The attack was still in progress. The situation was not clear. The air reports gave us scant help, for the airmen, unaccustomed to work with tanks, were optimistic beyond our wildest dreams, and reported tanks where no tank could possibly have been. I had given such careful orders to my tank commanders not to get ahead of the infantry, that with the best wish in the world I really could not believe a report which located a tank two miles within the German lines.

At last I drove up to see Haigh. I remember the run vividly, because four 9.2-in. howitzers in position fifty yards off the road elected to fire a salvo over my head as I passed, and at the same moment an ambulance and a D.R. came round the corner in front of us together. Organ, my driver—I had hired his car at Oxford in more peaceful days—was, as always, quite undisturbed, and by luck or skill we slipped through. I left the car by the dressing station outside the ruins of Heninel, which the enemy were shelling stolidly, and walked forward.

A few yards from Haigh's dug-out was a field-battery which the enemy were doing their best to destroy. Their "best" was a "dud" as I passed, and I slipped down, cheerfully enough, into the gloom. Haigh was away at brigade headquarters, but I gathered the news of the day from Head, whose tank had not been engaged.

The tanks had left the neighbourhood of the destroyed dump well up to time. It had been a pitch-black night at first, and the tank commanders, despite continual and deadly machine-gun fire and some shelling, had been compelled to lead their tanks on foot. They had discovered the "going" to be appalling, as, indeed, they had anticipated from their reconnaissances.

When our barrage came down, Mac's tank was in position one hundred and fifty yards from it. The enemy replied at once, and so concentrated was their fire that it seemed the tank could not survive. Twice large shells burst just beside the tank, shaking it and almost stunning the crew, but by luck and good driving the tank escaped.

The tank moved along the trench in front of our infantry, firing drum after drum at the enemy, who exposed themselves fearlessly, and threw bombs at the tank in a wild effort to destroy it. The gunners in the tank were only too willing to risk the bombs as long as they were presented with such excellent targets.

Mac was driving himself, for his driver fell sick soon after they had started. The strain and the atmosphere were too much for his stomach. You cannot both drive and vomit.

The tank continued to kill steadily, and our infantry, who had been behind it at the start, were bombing laboriously down the trenches. Suddenly the tank came to a broad trench running at right angles to the main Hindenburg Line. The tank hesitated for a moment. That moment a brave German seized to fire a trench-mortar point-blank. He was killed a second later, but the bomb exploded against the track and broke it. The tank was completely disabled. It was obviously impossible to repair the track in the middle of a trench full of Germans.

The crew continued to kill from the tank, until our infantry arrived, and then, taking with them their guns and their ammunition, they dropped down into the trench to aid the infantry. One man of them was killed and another mortally wounded. The infantry officer in command refused their assistance and ordered them back, thinking, perhaps, that they had fought enough. They returned wearily to their headquarters without further loss, but by the time I had arrived, Mac had gone out again to see if the attack had progressed sufficiently to allow him to repair his tank. He came in later disappointed. The fight was still raging round his tank. The German who fired the trench-mortar had done better than he knew. The disabled tank was the limit of our success for the day.

The second tank was unlucky; it set out in the darkness, and, reaching its appointed place by "zero," plunged forward after the barrage. The tank reached the first German trench. None of our infantry was in sight. The ground was so broken and the light so dim that the tank commander thought he might have overshot his mark. Perhaps the infantry were being held up behind him. He turned back to look for them, and met them advancing slowly. He swung again, but in the deceptive light the driver made a mistake, and the tank slipped sideways into a trench at an impossible angle. Most tanks can climb out of most trenches, but even a tank has its limitations. If a tank slips sideways into a certain size of trench at a certain angle, it cannot pull itself out unless it possesses certain devices which this Mark I. lacked. The tank was firmly stuck and took no part in the day's fighting.

The third tank ran into the thick of the battle, escaping by a succession of miracles the accurate fire of the German gunners. It crashed into the enemy, who were picked troops, and slaughtered them. The Germans showed no fear of it. They stood up to it, threw bombs and fired long bursts at it from their machine-guns. They had been issued with armour-piercing bullets, and the crew found to their dismay that the armour was not proof against them. Both gunners in one sponson were hit. The corporal of the tank dragged them out of the way—no easy matter in a tank—and manned the gun until he in his turn was wounded. Another gunner was wounded, and then another. With the reduced crew and the tank encumbered by the wounded, the tank was practically out of action. The tank commander broke off the fight and set out back.

While I was receiving these reports in the dug-out, Haigh had returned from brigade headquarters. The news was not good. The infantry could make little or no impression on the enemy defences. When attacking troops are reduced to bombing down a trench, the attack is as good as over, and our attack had by now degenerated into a number of bombing duels in which the picked German troops, who were holding this portion of their beloved Hindenburg Line, equalled and often excelled our men.